This post is an entry in our ninth annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest. This year’s theme is “Light.”

By Alexandra Miller

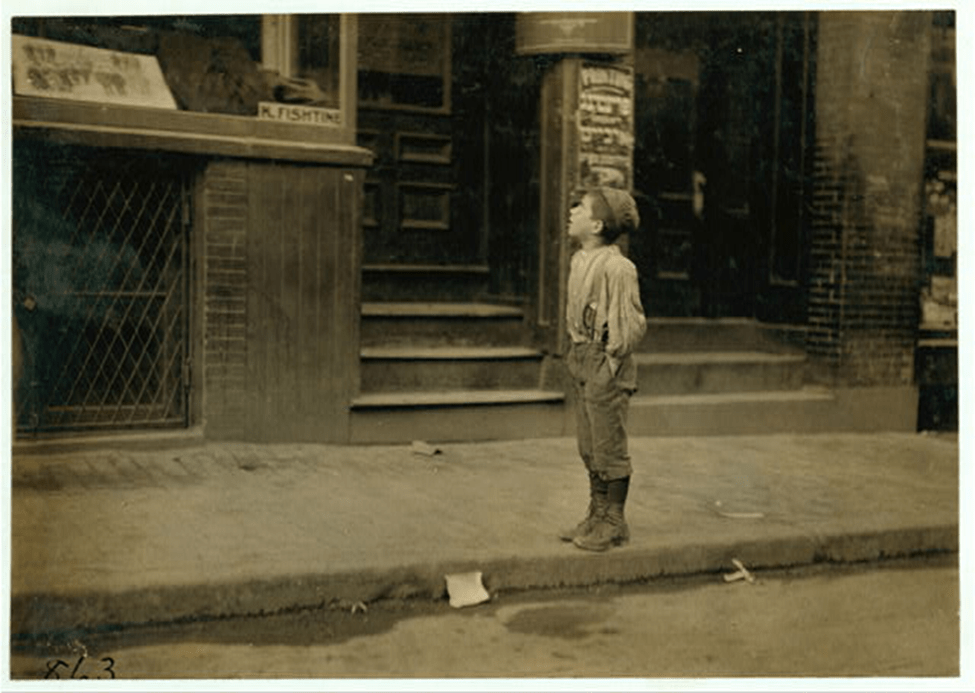

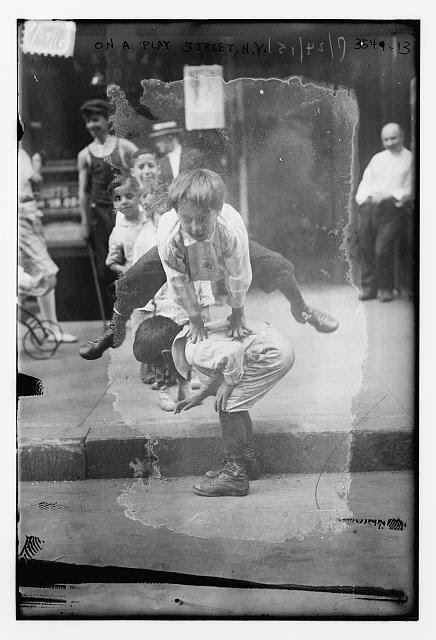

BOOM! The sound of the explosion “Shook the houses broke Window panes and caused a great excitement among the respectable portion of the tenants” of the midtown Manhattan neighborhood around the corner of 56th Street and 9th Avenue. It was 9 or 10 o’clock in the morning in mid-June, 1887. In the summer, New York streets were alive with people desperate to get out of their broiling homes. The adults on the block, mostly laborers and domestic servants, would likely be out at work during the day. But on a bright summer morning like this one, the neighborhood boys, out of school for the season, would be on the street in full force. They might play baseball, pitch pennies, or run races. Their sisters might sit on the stoops, tending to younger siblings. The soft sounds of their chatter and high-pitched giggles, interspersed with the shouts of the boys, would have drifted throughout the air. This hum would be punctuated by the rumble of the Ninth Avenue elevated railroad, the continual staccato and rattle of horse and cart street traffic, dogs barking, and the cries of newsboys hawking the last of their morning papers.

The sudden explosion ripped into this typical Manhattan morning. The air suddenly smelled of burnt hair and feathers. Splinters whipped through clothes hanging on the line. People standing on the street suddenly saw chunks of smoldering wool flung in every direction. A great tumult began among those in the street. Attracted by the prime opportunity for gossip, people peered out windows or walked over to the empty lot on the south side of the block to investigate. What they saw were the remnants of an old bed and mattress, exploded by “some Rock Rend or Dynamite,” and still burning. Those gathered agreed that none of the boys on their block would do such a thing, and that it must be “unknown boys” from some other neighborhood.

Despite their confidence that the culprits must be boys foreign to the neighborhood, the 56th Street gossips identified what many urban residents perceived to be a threat to public order: young people. That fact remains true today. I live now in Washington, D.C., a city currently under military occupation and which is imposing juvenile curfews in many downtown zones to combat what some believe to be a rash of youth crime, including the shooting of fireworks at windows and cars.1 At the turn of the century, however, New York adults instead tried to direct petty youth crime towards their own civic ends. Boys in Manhattan formed neighborhood street “gangs,” which shared the ethnic tilt of their block. Though occasionally these gangs warred with their neighbors, they spent the bulk of their time on the street in play. One of their preferred games was blowing things up. Though fireworks on their own are not a threat to urban order, and in fact have a long civic tradition in the United States, what adults could not tolerate was their use in a way that was out of sync with the city’s. New York adults expected displays like fireworks and bonfires to serve civic functions and thus to be kept to civic days, like Independence Day and Election Night. Boys, with their year-round play, confounded that civic goal.

Two weeks after the blast, on the night of June 26th, another explosion rang out from another empty lot on 56th Street. This time it was fireworks. On a Sunday night like this one, the block would be full of people sitting out on their stoops, enjoying their day of rest. They were likely to have been grumbling about the cost of replacing the windows broken by the earlier explosion. This second explosion, with no dynamite involved, was more spectacular and caused a much greater commotion on the more densely peopled street. It was on this occasion that an anonymous “American” wrote to Mayor Abram S. Hewitt to complain of the rash of explosions. The author worried aloud that the “young roughs have got quite a number of peices [sic] of the Same material which they intend to set off on the 4th.” A subsequent police investigation revealed that no neighborhood boys had a cache of fireworks, dynamite, Rock Rend, or other explosives.2

Perhaps the 56th Street boys had no fireworks stashed away, but they would have been in the minority. New York boys were pyromaniacs. Starting fires and setting off fireworks were a few of the many ways in which boys had fun in the city. Grown memoirists fondly remembered setting these fires. On a Saturday afternoon in 1913, the People’s Institute conducted a survey of Manhattan children and found over six hundred engaged in something to do with fire, whether setting the bonfires or gathering kindling. In a study of 170 juvenile delinquency court cases, they found that over 11% of the boys were jailed for setting bonfires.3 People across the city wrote to the mayor complaining of fireworks and other fires set by boys in vacant lots and on street corners. While fireworks offered excitement, they could pose real dangers. Children frequently suffered burns from fires.4 Michael Gold remembered one July 4th when a firecracker fell onto his sidewalk bed, scarring him.5 And Harry Roskolenko recalled a fire-prone urban environment in which “the tenements were made of bricks, wooden stairs, wooden floors, wooden doors–and great fires were as common as the cold.”6 And yet, there were annual occasions when adults not only allowed boys to set off fireworks and start bonfires, but actually encouraged it.

Although playing with fire was part of regular play for New York boys, the city’s adults deemed fireworks and bonfires appropriate only under certain civic circumstances. At different ages, their rhythms for using the city’s public spaces operated on significantly different time scales. The primary constraints on boys’ time were school or work and whatever time their mothers called them inside. The instant gratification of an explosion was something that could be easily slotted in amidst their baseball games and homework. Adults instead operated on an annual calendar. They saw fireworks as an appropriate display for July 4th, and bonfires as proper only for election night in November. The warring priorities of fun and civic participation moved at different speeds. Adults wanted to bring children’s play into the productive fold.

July 4th fireworks have a long civic tradition in the United States, and New York is no different. Boys saw no reason to limit the fun of fireworks to a single day. They set off blasts throughout June and July, leading up to the celebration of Independence Day. When the mayor received adult complaints, he forwarded them to the Department of Police, which investigated and often pointed the finger at young boys. On one occasion, Police Captain Robert O. Webb replied to a complaint about fireworks that he did not believe any were set off because there were “not very many children residing in the vicinity.”7 In one instance, Samuel Goldberg, 14, and Charles Leary, 17, were arrested, arraigned in the 4th District Police Court, and fined $1 each.8 Far more often, the culprits were too young to arrest. In these cases, officers instead warned the children and their parents against further explosions.9

But no matter how much of a nuisance New Yorkers found fireworks on any other day, they were perfectly acceptable on July 4th. One complainant, J.R. VanDerveer, made the adult fireworks calendar explicit in his complaint about “the premature firing of crackers and rockets” on his street when he asked the police “if the enthusiasm of the small boy can be checked until the 4th July.” Despite the age of the culprit, in his eyes, any fireworks would be permissible on the national holiday.10

The same scheduling disagreement raged over bonfires. New York had a long tradition of setting bonfires all over the city on election night. For Tammany Hall supporters, engaging in the parades and bonfire night was a point of pride. Despite the fires being banned by the police, “every election night sees the sky made lurid by them from one end of town to the other.”11 Comedian Harpo Marx remembered that on election night, Tammany forces would parade down the city’s avenues, handing out free beer to men and firecrackers and kindling to children.12 Many memoirists remembered building election night bonfires.13 Clearly, on one day a year, New York adults encouraged children to light bonfires to fulfill political end. The bonfires had popular adult and party backing, though not legal standing.

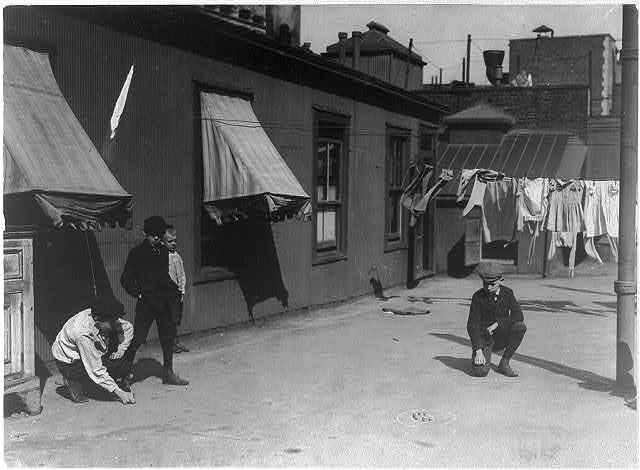

But the kindling which adults distributed on election day was not enough for a true spectacle. For months in advance, gangs of boys stole fuel and stashed it away in their neighborhood territory, often storing it in vacant lots on their block. Boys were fiercely protective of their kindling stores and very proactive in procuring their fire materials. James L. Stikeman griped about a lot near his home which children broke into and stored barrels for election night. He asked that they be arrested, alleging that the boy culprits attacked those who removed their stolen wood with stones.14 The People’s Institute recorded an incident in which the boys of 53rd Street ran out of bonfire material then raided the 50th Street stash, sparking off a yearlong feud.15 Jacob Riis even claimed that once “an entire frame house has been carried off piecemeal, and burned up election night.”16

Despite calling the election day firestarters “Embryo voters,” during the rest of the year, New Yorkers constantly complained of children gathering fuel for their fires.17 They wished that the boys would keep their bonfires to election night, the only acceptable time for such a demonstration. To New York adults, the only proper purpose for a bonfire was civic, rather than amusement. By taking the bonfires beyond election night, the boys disrupted neighborhood life.

But boys did not see fire as having a purely civic purpose. For many of them, it was a social activity and thus belonged to the whole year. Samuel Ornitz recalled in his memoirs that boys would gather on corners to light fires in milk cans, always having to run off when the police approached.18 They also lit fires in vacant lots, as in the case of the mattress from the beginning of this blog. Because local businesses bordering these lots often used the empty space for storage, boys could easily procure more kindling. This could touch off neighborhood conflict. In the Bronx, Mrs. Secare complained that the grocer standing across an empty lot from her gave boxes of refuse to the neighborhood boys, which they used to build summer bonfires that threatened her house.19

As I write this, I have sporadically heard fireworks going off in my own neighborhood, long after the July 4th display. But I do not expect that they will stop. As the New York police acknowledged in 1904, “the total suppression of this evil [fireworks] would be difficult to accomplish.”20 Rather than purely policing the youth of today, we might look to the example of New York. Though we may no longer have civic bonfires and most cities discourage personal fireworks, we can still redirect youth energy towards more productive channels. Instead of looking to a military police force, we might look to Baltimore, which is investing in youth mentorship, education, and recreation and as a result saw a significant reduction in homicides and non-fatal shootings.21

Alexandra Miller is a doctoral student at George Mason University. She works as a Graduate Research Assistant in the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media.

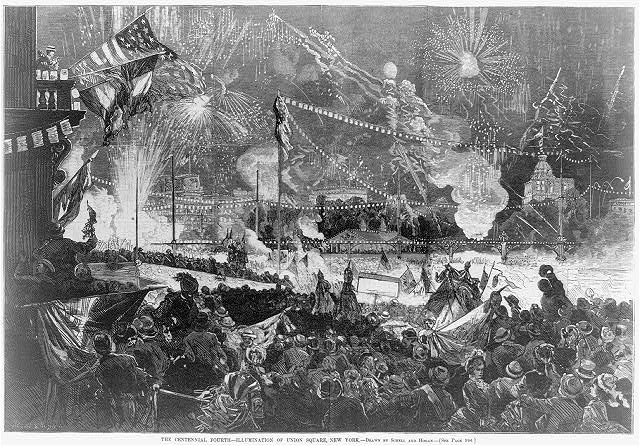

Featured Image (at top): Fourth of July celebrations Union Square, New York, engraving, 1876, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

- Luke Lukert, “DC mayor toughens summer curfew after 20 teens charged with fireworks offenses,” WTOP News, July 8, 2025; Brian Mann, “Trump’s Washington, D.C., takeover targets a host of groups, many of them vulnerable,” NPR, Aug. 12, 2025. ↩︎

- An American to Abram S. Hewitt, June 27, 1887, series 27, box 157, folder 175, Office of the Mayor: EM, NYMA; Patrick H. Pickett to William Murray, July 8, 1887, series 27, box 157, folder 175, Office of the Mayor: EM; NYMA. Underlining original. ↩︎

- John Collier, Edward M. Barrows, The City Where Crime is Play (People’s Institute, 1914), 27, 43.

↩︎ - Harry Roskolenko, The Time That Was Then: The Lower East Side, 1900-1914, An Intimate Chronicle (The Dial Press, 1971), 160. ↩︎

- Michael Gold, Jews Without Money (Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1930), 142.

↩︎ - Roskolenko, The Time That Was Then, 48. ↩︎

- Robert O. Webb to William Murray, June 30, 1887, series 27, box 157, folder 174, Office of the Mayor: EM, NYMA. ↩︎

- George S. Chapman to Nicholas Brooks, June 24, 1895, series 30, box 301, folder 344, Office of the Mayor: EM, NYMA. ↩︎

- William McAdoo, General Order No. 75, June 20, 1904, Police Department, series 1, box 54, folder 527, Office of the Mayor: George B. McClellan, NYMA.

↩︎ - J.R. VanDerveer to Abram H. Hewitt, May 26, 1887, series 27, box 157, folder 173, Office of the Mayor: EM, NYMA.

↩︎ - Jacob Riis, The Children of the Poor (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 74. ↩︎

- Harpo Marx and Rowland Barber, Harpo Speaks! (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2017), 80. Original publication 1961. ↩︎

- Samuel Chotzinoff, A Lost Paradise: Early Reminiscences (Alfred A. Knopf, 1955), 89; Marx, Harpo Speaks!, 80-81. ↩︎

- James Stikeman to William L. Strong, Oct. 22, 1895, series 30, box 301, folder 347, Office of the Mayor: William L. Strong, NYMA. ↩︎

- Collier and Barrows, City Where Crime is Play, 23. ↩︎

- Marx, Harpo Speaks!, 80; Riis, Children of the Poor, 74; Mark Brewin, “The History and Meaning of the Election Night Bonfire,” Atlantic Journal of Communication 15 (2007): 153-169. ↩︎

- Brewin, “History and Meaning of Election Night Bonfire.” ↩︎

- Samuel Ornitz, Haunch, Paunch, and Jowl (Garden City Publishing Company, 1923), 19. ↩︎

- Mrs. Secare to Thomas F. Gilroy, Aug. 1893, series 29, box 252, folder 136, Office of the Mayor: EM, NYMA.

↩︎ - William McAdoo, General Order No. 75.

↩︎ - Christian Olaniran, “Mayor Scott touts violence reduction, increased youth programs in first term report,” CBS News, July 1, 2025. ↩︎