By Ryan Reft

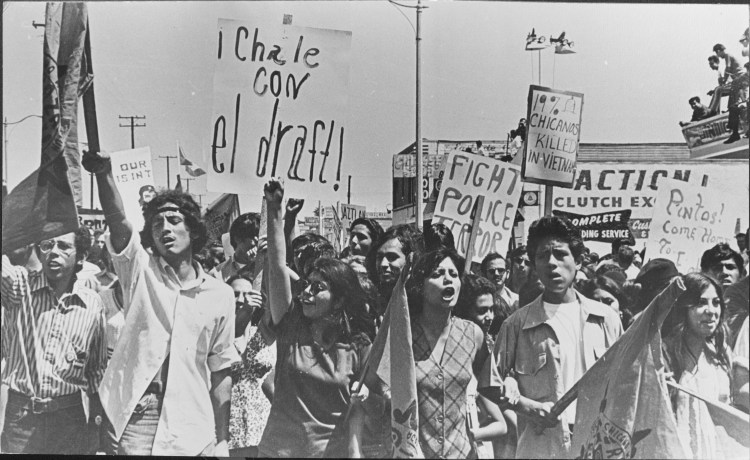

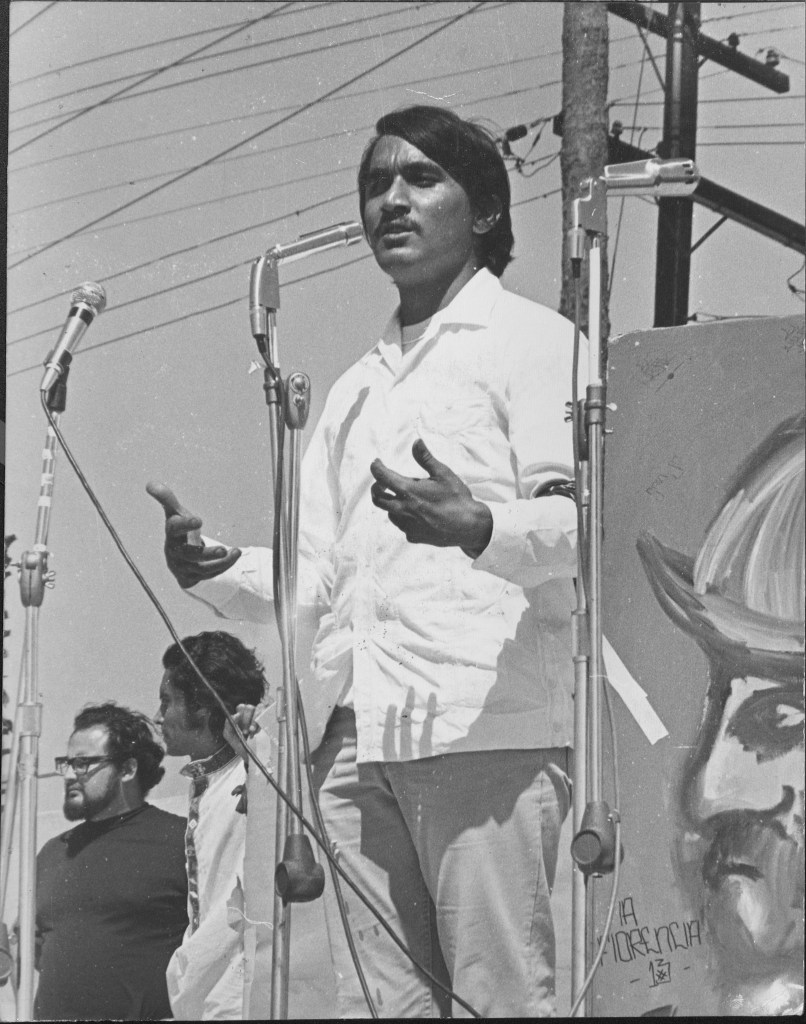

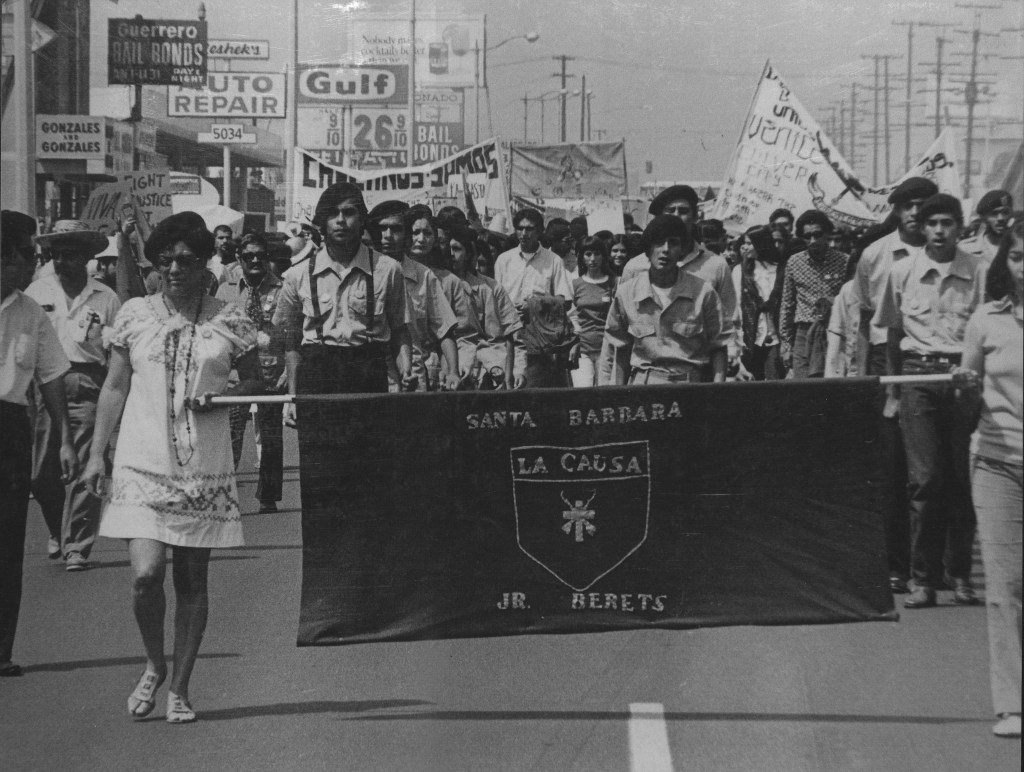

It was late afternoon on August 29, 1970, when Rosalío Muñoz, chairman of the National Chicano Moratorium Committee (NCMC) stood before thousands of people under a hot southern California summer sun. He was briefly triumphant, having stewarded the nation’s largest ever Mexican American protest and the largest by a single ethnic group, as 20,000 to 30,000 people gathered to march against the Vietnam War. The demonstration drew attention to what Muñoz and others saw as both an unjust war and one that had disproportionately cost the lives of Chicano soldiers.

The events that followed Muñoz’s remarks, namely the law enforcement-induced riot, shaped the national Chicano movement and Los Angeles Mexican American community in profound ways while hardening opinions regarding the relationship of each to law enforcement. While the 1970 march has received a great deal of attention from historians, the inquest that followed has not, particularly testimony by figures like Mexican American housewife Cora Barba, who embodies not only the political motivation behind the demonstration but also serves as a window into the developing political consciousness of the city’s Mexican American residents.

Onstage at Laguna Park in 1970, Muñoz recounted how a year earlier “there had been few of us.” Yet within twelve months, the Chicano anti-war movement and NCMC had become “a powerful force for social change.” Still, Muñoz said, while opposing the Vietnam War remained critical, the Chicano movement must also look to other issues, namely, police brutality. He told listeners: “We have to bring an end to this oppression.”[1]

In the moment, Muñoz could not have known the irony of his statement. Minutes later, he watched as “a line of deputies… suddenly appeared on the edge of the park and started pushing forward,” writes historian Lorena Orepoza in !Raza Sí! Guerra No!, her work on the 1970s Chicano movement.[2]

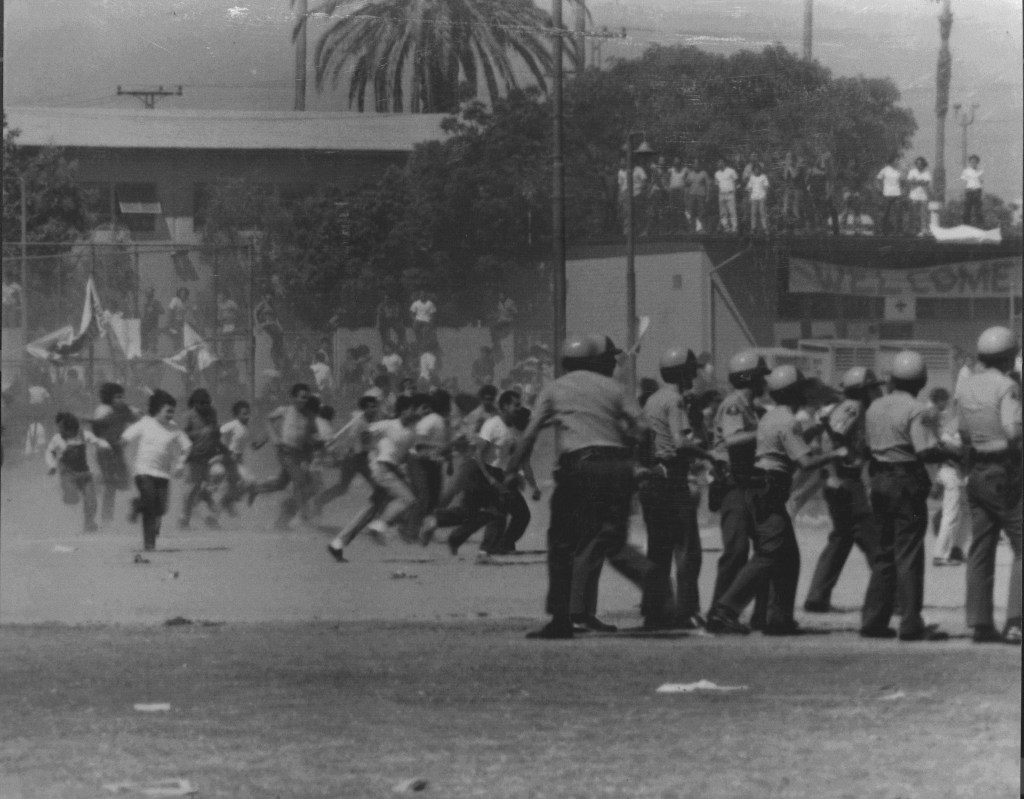

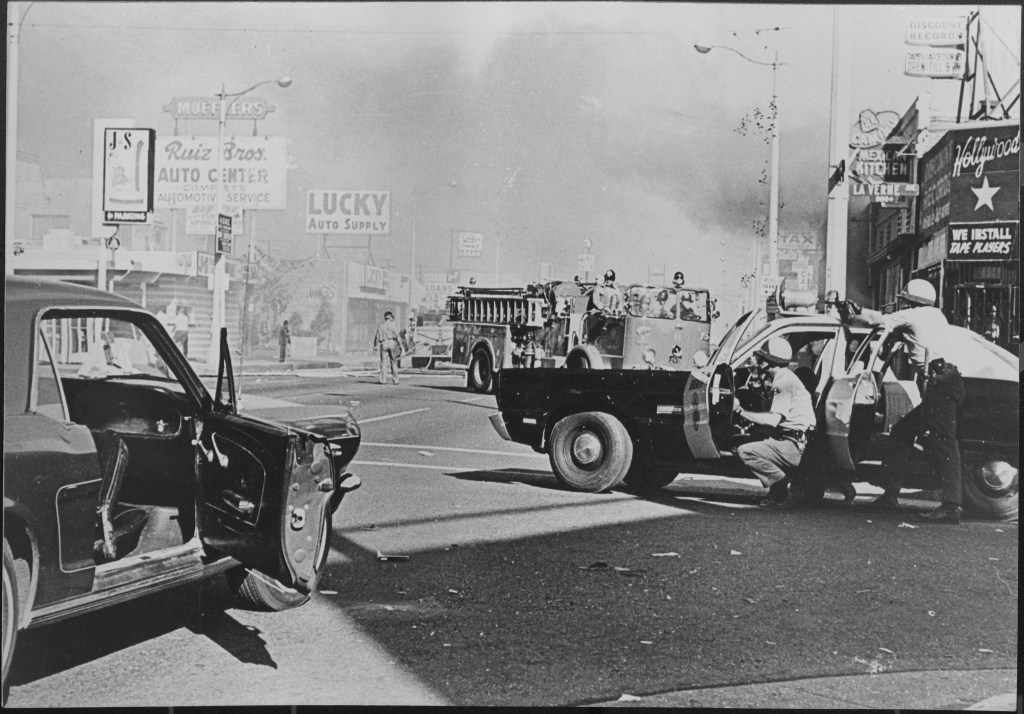

NCMC’s August 1970 march was the third and largest moratorium march against the Vietnam War in Los Angeles since December 1969. It represented the apex of the Chicano movement’s national profile, bringing together a diaspora of American activists and Americans of Mexican American heritage from California, the Southwest, and a handful of other states. The march would also serve as a crucible for both the Chicano Movement and local law enforcement, including the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Due to East Los Angeles’s unincorporated status, the latter was responsible for policing the event and while aided by the LAPD, was largely responsible for the demonstration’s suppression, and according to many witnesses, instigating its violent turn altogether.

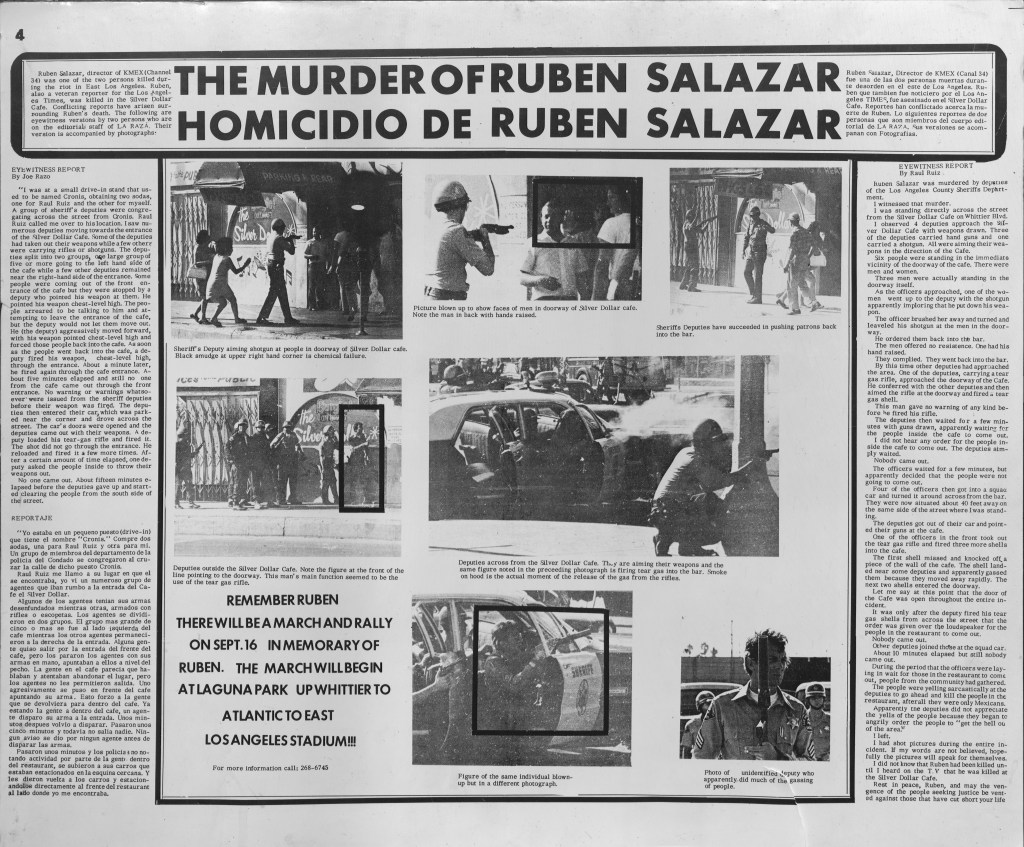

Law enforcement arrested over 200 people, 60 were injured, and roughly $1 million in property damage was caused at the chaotic march.[3] Three people died, including Los Angeles Times columnist and KMEX news director Ruben Salazar, who was killed when Los Angeles deputy sheriffs fired tear gas projectiles into the Silver Dollar Bar on Whittier Boulevard. Salazar’s death, the result of overly aggressive policing, sparked widespread indignation. Although it may have gone unchallenged if not for photographic documentary evidence provided by La Raza photographer and co-editor Raul Ruiz, who, along with other photographers from the magazine, captured the incident as it unfolded.

Anger and confusion over Salazar’s death and the larger law enforcement response to the march resulted in demands for an inquest. Known as the Salazar Inquest, the sixteen day-long county-run fact-finding mission heard 61 witnesses and over 200 pieces of evidence. It produced over 2,000 pages of testimony. Local television carried its proceedings. The inquest was a “quasi-judicial proceeding” that could not impose any real legal ruling, according to Los Angeles Times journalist Paul Houston, who covered it at the time. Still, Houston wrote, due to local coverage on television and print, it was “imbued with the drama of a major event.”[4] Despite disappointment in its eventual conclusion, the inquest did produce an explanation for what had happened that August afternoon in 1970 and how Salazar died, even if the actions of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department remained questionable and motives elusive.

Though it was described as repetitive by the Los Angeles Times and others, the inquest had real moments of cinematic drama that highlighted issues relevant then and now. Journalist Hunter S. Thompson, who followed the hearing through the Times, described its coverage as a ”finely detailed, non-fiction novel.”[5]

Ruiz’s own testimony remains arguably the most notable because it provided Mexican Americans with an assertive, skeptical voice in the face of attempts by law enforcement to downplay its own mistakes, and possibly, maliciousness. Another witness, Cora Barba, the 57th person to testify, captured the radicalizing nature of the protest and law enforcement’s response to it for Los Angeles’ Mexican Americans.

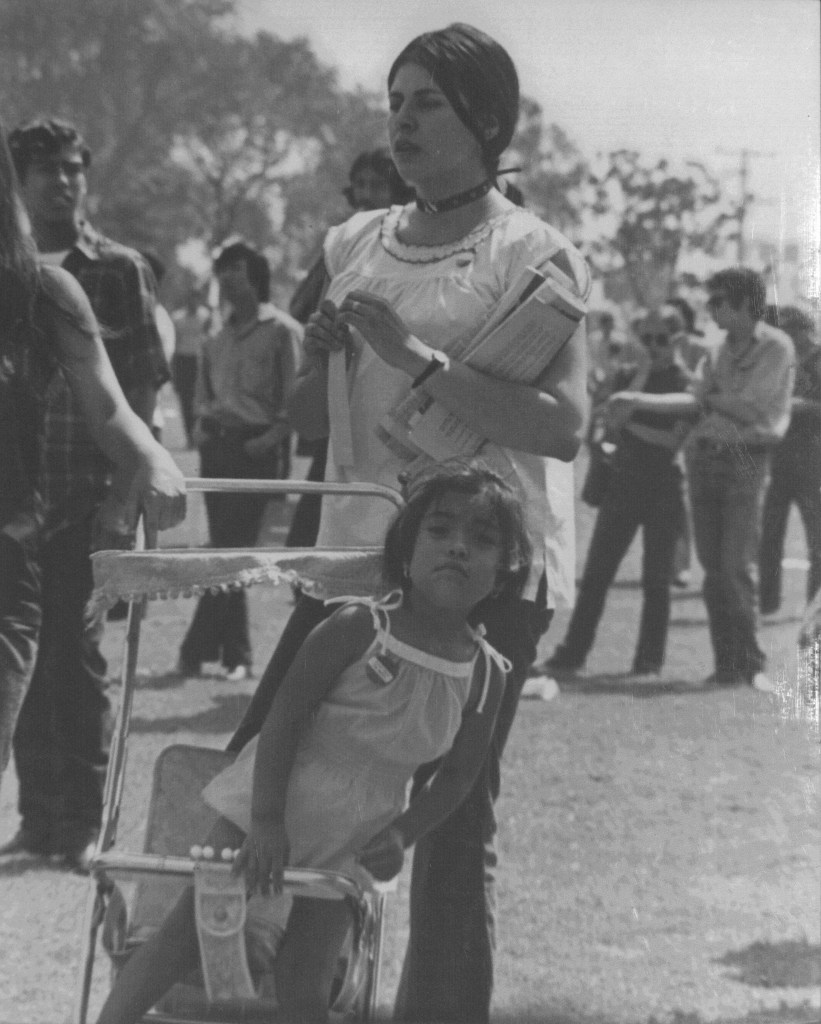

A Mexican American housewife and mother of a soldier serving in Vietnam, Barba’s testimony demonstrates not only the burgeoning ethnic unity following Salazar’s death, but also the growing chasm between her community and law enforcement.

Barba, who had brought her 11 year-old neighbor Billy to the march, had begun at the wrong location, noted Ruiz in his unpublished manuscript, now available in his collection at the Library of Congress, about the inquest. The pair arrived at a “grassy knoll on Brooklyn Boulevard near the Maravilla Housing Projects,” where they ran into a group of “Anglo boys, about 20, 23, 24 years old,” with three “Mexicans” and “few” African Americans.[6] The young men, who were handing out pipes and Chairman Mao stickers, were identified as members of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). The group was a thorn in the Chicano Movement’s side. According to Muñoz, members of the PLP had visited planning meetings for NCMC’s protest and criticized its larger goals, arguing that the focus on Chicano soldiers disrupted “working class unity” because it “emphasized the return of Chicano soldiers instead of all G.I.’s”.[7]

Her interaction with the PLP members unsettled Barba, but she was still determined to participate in the march. She eventually found her way to her contingent and joined the demonstration, soon realizing, however, that PLP was in front of her and county deputy sheriffs behind. “If something happened, I was going to be in the middle of it,” she recalled at the hearing.[8]

Barba and Billy walked the three and a half miles to Laguna Park, where they settled in for hamburgers, entertainment, and speeches. As Billy returned with the burgers, Barba looked up and “all of a sudden… saw a bunch of dust, and the police were coming.” She immediately rose and bolted with Billy. The pair told a 63 year-old woman they encountered to run as well, but she didn’t.

“She wanted to see what was happening,” Barba recalled at the inquest. She and Billy, on the other hand, took no such chances. They ran to the first house near them and stood on the porch to watch as events played out. Barba watched helplessly as a sheriff’s deputy approached the old woman and “beat her up with a baton on the head [until she] just went out like a rag.” Barba yelled at the deputy to stop. He eventually did, walking off with little concern for his elderly victim. Barba never saw anyone pick the woman up. She told the inquest: “I don’t know what happened to her.”

During the riot, Barba witnessed this sort of violence repeatedly. “Because two or three officers – and sometimes six – would get a boy, and [would beat] him up, and then they would go and get somebody else.” When deputies ordered her into the house, she responded that she couldn’t enter the home since it wasn’t hers. One of the deputies who issued the order then threw tear gas at her and Billy; the projectile ended up gassing the young boy “right in the face.”[9]

This first portion of Barba’s testimony contradicted the larger narrative set by municipal authorities. Before the inquest, Los Angeles law enforcement and political leadership described the Mexican American community in paternalistic terms, claiming it was easily influenced by outsiders and vulnerable to “communism.” When the inquest began, law enforcement and politicians pointed the finger at Mexican Americans. “Police set the tone of the investigation on the first day when Captain Thomas W. Pinkston unhesitatingly blamed the violence on Chicanos,” notes historian Ernesto Chavez.[10]

In contrast, Barba described what most participants experienced: a relatively uneventful march followed by a brief picnic respite at Laguna Park before the sheriff’s department closed in on the crowd. The violence she witnessed went in one direction and victimized the most vulnerable members of the community. Additionally, her experience with the PLP illustrated that the handful of alleged “troublemakers” who participated in the event weren’t even tied to the Chicano movement or the Mexican American community. As Ruiz noted, “provocateurs of the Anglo community variety instigated the police that were already ‘chomping at the bit’ to beat and suppress the growing activist movement that was rapidly growing in the Chicano community.”[11]

Admittedly, some who attended the event believed that the Chicano community needed to express its frustration violently. Muñoz told historian Mario T. Garcia that he recalled one conversation with a member of the Brown Berets, a militant Chicano group, who said, “We need to have a riot like the blacks. That’s the only thing that whites pay attention to… the people want a riot.”[12] However, in general, during the three-and-a-half-mile march, thanks in part to monitors stationed throughout, who functioned as both buffers and liaisons between marchers and law enforcement, few incidents of unrest occurred. Those that did were quickly mediated.

Finally, as historian Edward J. Escobar notes, Los Angeles law enforcement regularly deployed agent provocateurs in social movements, including the Chicano movement.[13] A 1978 class action suit against LAPD revealed “that LAPD officers had infiltrated several Chicano groups, including the Chicano student organization at California State Northridge, and had enrolled in Chicano studies courses there to monitor faculty members’ lectures.” Through such infiltration, “civilian agents and police officers sworn to enforce the law allowed, instigated, and engaged in illegal activity,” argues Escobar.[14] Between charges of communist influence and the actions of infiltrators which often confirmed such accusations and the deployment of state violence against Chicanos, law enforcement encouraged chaos and unrest, then responded accordingly.

Barba grew more emotional as her testimony continued. She also, whether purposely or not, drew a clear connection to the issues that had animated the march, including the war’s dependence on Chicano soldiers, and law enforcement’s treatment of the Mexican American community.

She had been at the Roosevelt High School protests in March 1969, when television cameras captured the LAPD beating demonstrators and dragging adolescent Mexican American students by the hair. Barba testified to a similar experience: “a policeman kicked me, and I had to go to a doctor for three weeks.”[15] “I don’t want the people to be blaming my people,” Barba said. “Everybody blames all Chicanos. And I’m proud of being a Chicana. I will always be a Chicana; if I have to die being a Chicana, I’m going to die being a Chicana! I don’t want them talking about my people that way.”[16]

As she continued with her testimony, Barba underlined her son’s service, her motherhood, and civil rights, an appeal that resonated with more conservative Mexican Americans of the World War II generation.[17] “I have my boy overseas, and I had a right to march there in that Moratorium, because I want the war to end. I want my boy,” she said. “If my boy has a right to be out there, and I suffer here without my boy, I know my rights and I want justice done.” The Times noted her pause and the emotional weight of the moment, writing that “[i]n a voice shaking with emotion Mrs. Barba plunged on uncertainly.”

Barba had given flesh to a point that Rosalio Muñoz had raised just days before the march. “Just as everybody in the barrio has somebody in the war, just about everybody here has been harassed by the police or knows someone in prison.”[18] Barba and Billy served as a case in point. Barba stated in no uncertain terms: “I am afraid of the police.”

Barba testified on the tenth day of the inquest, and it ended on the sixteenth day with a 4–3 decision declaring that Salazar had died at “the hands of another.” The phrase “at the hands of another,” according to Norman Pittluck, the hearing officer, “was not legally definable but was a ‘catch-all’ category for deaths that were not by ‘accident,’ ‘suicide’ or ‘natural causes.’” That explanation did little to assuage the Mexican American community’s anger.

In fact, according to one state legislator who spoke to the Times, Pittluck had framed the term incorrectly when he juxtaposed one possible ruling, “accident” with a second possibility “at the hands of another.” As defined by Pittluck, that latter seemed to indicate that deputies had intended to shoot and kill Salazar. However, according to State Assemblyman James A. Hayes, since the deputies clearly meant to fire into the tavern, it could not have been ruled an “accident,” thus, the only decision that the jury could come to was “at the hands of another.” The term did not mean they meant to kill Salazar, but rather had intended to fire into the bar but Pittluck interpreted and presented that way, which blunted the jury’s ruling. Whether or not law enforcement intended to kill Salazar was irrelevant for that latter verdict, which again held no binding legal standing.[19]

Pittluck’s definition led three jurors to balk at asserting the majority verdict, since several believed law enforcement to have acted thoughtlessly, but not with intent to kill. The jury foreman, one of the three dissenting votes, told the Times that Pittluck’s instructions “blew his mind.” However, based on those instructions, he wanted to avoid emotion and rule on “reason.” He added that in the end, all seven jurors believed law enforcement to be at fault. While unlikely, a unanimous decision might have compelled the district attorney to pursue charges. More importantly, such a decision would have provided a more definitive outcome, and while it probably would not have softened resentment among the city’s Mexican American community, might have at least given it a sense that it had been heard.[20]

In interviews with the Los Angeles Times, the jurors clearly expressed their view that law enforcement had acted recklessly and dangerously at the NCMC march. “The entire jury felt there was definite negligence on the part of the sheriff’s department and that the deputies did not use discretion or prudence in their acts that day,” one juror told the newspaper. “The main surprise to me was the deputies’ lack of organization, their lack of consideration for innocent people…I think if these same officers had been in Beverly Hills, they would have acted entirely different under similar circumstances.”[21]

Hunter S. Thompson observed that Los Angeles’ Mexican American community had become more politically conscious. Thompson observed that middle-aged housewives, like Barba, who would have never considered themselves Chicanas, “suddenly found themselves shouting ‘Viva La Raza’ in public.” Their husbands, “quiet Safeway clerks and lawn-care salesman,” have been transformed and “were volunteering to testify; yes, to stand up in court, or wherever, and call themselves Chicanos.”[22]

As Escobar notes, over the ensuing decades, Mexican Americans realized that, whatever issues the more conservative community members had with the more militant Chicano movement, they all needed to build political power and challenge their treatment in the courts. “While most people of Mexican descent still refused to call themselves Chicanos,” observed Escobar, “many had come to adopt many of the principles intrinsic in the concept of chicanismo.”[23]

Over fifty years after NCMC’s August 29, 1970 protest and Salazar’s death, Barba’s testimony and the inquest itself remind us that even dark moments can lead to brighter outcomes. Salazar’s killing shocked Latinos across the nation. For Angelenos, it was a gut punch. Though not of the Chicano movement, Salazar was a rising voice for Mexican Americans and a burgeoning media star silenced by a system of law enforcement that continued to treat the broader community with contempt and disregard. It undoubtedly took the wind out of the Chicano movement’s sails as subsequent demonstrations were stricken by violence between protesters and law enforcement, leading to an eventual cessation of marches. Yet, more broadly among Mexican Americans, it also sparked a significant expression of cultural and political solidarity, leading to inroads throughout the power structure of the city. Unfortunately, the march, its aftermath, and the inquest that followed also failed to solve or mediate issues regarding police-community relations or policing, whether by municipal, state, or federal law enforcement. The outcome to these three connected events remains ambivalent. But then again, so was the inquest. Nearly six decades later, many of the issues animating the moratorium remain as relevant as ever.

Ryan Reft is senior editor of The Metropole. His work has appeared in academic journals such as the Journal of Urban History, Washington History, and California History and popular outlets such as the Washington Post, Philadelphia Inquirer, Zócalo Public Square, and the Saturday Evening Post among others. He co-edited and contributed to East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte (Rutgers Press) and Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth about Urban Highways (Island Press).

Featured image (at top): Chicano protesters march down Whittier Boulevard for the National Chicano Moratorium Anti-Vietnam War March, Raul Ruiz, photographer, August 29, 1970, Raul Ruiz Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Lorena Oropeza, !Raza Sí! Guerra No! Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Vietnam Era, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005), 160.

[2] Oropeza, 161.

[3] Mike Castro and Frank del Olmo, “Newsman Salazar Becomes Legend to Some Latins,” Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1975.

[4] Dave Smith, “Jury Splits on Salazar Death,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1970; Ernesto Chávez, Mi Raza Primero: Nationalism, Identity, and Insurgency in the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles, 1966-1976. Los Angeles: University California Press, 2002, 71-72.

[5] Hunter S. Thompson, “Strange Rumblings in Aztlan,” in Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: the Essential Writings of Hunter S. Thompson, ed. Jann S. Wenner. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011, 56.

[6] Raul Ruiz, “Silver Dollar Death: The Murder of Ruben Salazar,” 2010, 215. Box 21, Raul Ruiz Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; Roger K. Williams and Max D. DeCamp, “Reporters’ Daily Transcript: Inquest Held on the Body of Ruben Salazar.” Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office, September 24, 1970, 1238. Box 17, Raul Ruiz Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[7] Oropeza,154.

[8] Ruiz, 216

[9] Ruiz, 216-218; Roger K. Williams and Max D. DeCamp, “Reporters’ Daily Transcript: Inquest Held on the Body of Ruben Salazar.” Los Angeles County Corner’s Office, September 24, 1970, 1244. Box 17, Raul Ruiz Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[10] Chávez, 71.

[11] Ruiz, 217.

[12] Manuel T. Garcia, The Chicano Generation: Testimonies of the Movement. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2015, 272.

[13] Edward J. Escobar, “The Dialectics of Repression: The Los Angeles Police Department and the Chicano Movement, 1968-1971,” Journal of American History Vol 79, No. 4, March 1992, 1485.

[14] Escobar, 1511, 1498.

[15] Dave Smith, “Woman Scores Both Deputies and Militants,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1970.

[16] Dave Smith, “Woman Scores Both Deputies and Militants,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1970.

[17] Dave Smith, “Woman Scores Both Deputies and Militants,” Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1970.

[18] Oropeza, 147

[19] “Inquest Can Make 1 Ruling Legislator Says,” Los Angeles Times, September 22, 1970.

[20] Paul Houston, “4 Salazar Jurors Rap Deputies,” Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1970

[21] Paul Houston, “4 Salazar Jurors Rap Deputies,” Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1970.

[22] Thompson, 48.

[23] Escobar, 1511.