Editor’s note: This is the fourth post in our theme for April 2025, The City Aquatic. For additional entries in the series, see here.

By Emi Higashiyama

The story of Taiwan’s emergence into modernity can be difficult to interpret because it is a story that has been caught in the fierce rivalry between China and Japan, essentially a football being kicked and tossed between the two opposing powers, each seeking to control and reshape it according to their own ambitions. Although the imperial Japanese control of Taiwan was short-lived (only fifty years from 1895 to 1945), the legacy and significance of water engineering catapulted a backwards subtropical island into modernity that has since set the tone for Taiwan’s progressive urban planning. When Qing Dynasty China ceded the island of Taiwan to the Empire of Japan in 1895, even the most established cities were malaria-riddled holdovers from previous colonization attempts by Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch traders. Piracy was a constant threat, and city planning was on an ad hoc basis determined by warlords. With Chinese dynastic rule in decline, and simultaneous wars competing for administrative attention, Taiwan was considered a hinterland territory that did not merit much government investment.

After Taiwan officially became an island of Japan with the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, the Japanese military governed this outpost for the first phase of experimental colonialism. Once safety was assured – and natural resources were identified that would prove valuable to imperial causes – Japanese colonists embarked on a mission to turn Taiwan into the ideal colony and set to work organizing and modernizing its cities, all while harvesting Taiwan’s sugar cane, rice, timber, tobacco, tea, and tropical fruits. Fresh from its forays into modernity, Meiji Japan was eager to reap the rewards of its commitment to water engineering, a worthy investment to harness Taiwan’s natural abundance to build the empire’s agricultural wealth. [1]

Led by Shinpei Gotō, who was a physician by training, the colonial machine set to work taming the island by controlling its water. Gotō had previously made a name for himself in military hospital administration, and was subsequently promoted through civic channels to become the head of the Home Ministry’s medical bureau. In 1890, he achieved new career heights with the publication of his Principles of National Health and his involvement in the development of sewage and water management infrastructure in Tokyo. When the first transition of colonial administration from military leaders to civil servants was underway, Gotō was the man of the hour and appointed as the head of civilian affairs in Taiwan.

One of Gotō’s first acts was ordering a land survey for the purpose of methodical city planning, the center of which was a sanitation system to support the administrative capital of the new colony – effectively a repeat of what he had done earlier in Tokyo. These initial efforts to transform Taiwan were part of his broader plan to modernize Taiwan by exerting control over its natural wilderness, to tame and domesticate it, all to increase its productivity for the Japanese empire. By improving sanitation, Gotō was addressing the major obstacle to Taiwan’s economic development – better public health would reduce mortality rates, fostering a more stable and productive workforce. A social and cultural benefit to Gotō’s method was ensuring Taiwan’s population would be dependent on Japanese administration for daily needs and well-being, thus solidifying Japanese authority. Internationally, the success of Gotō’s administration would show the world that Japan could manage its empire in a sophisticated and orderly manner. [2]

Gotō hired Scottish engineer William Kinnimond Burton to build infrastructure for making water potable as well as a system for waste disposal. Burton’s storied life and career mirrors much of Gotō’s (though perhaps with more mystery and historical flare) – he provided technical information to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, earning him a dedication in one of Conan Doyle’s books. Unlike the formally educated Gotō, however, Burton was largely self-taught – and it was while he was ascending the ranks of the London Sanitary Protection Association that he received an invitation to teach at Tokyo Imperial University. Although no one quite knows how Burton was selected to be the prominent foreigner working for the Japanese government, he was nonetheless accepted by a society that had previously vigorously upheld isolationist policy. By the time Burton went to Taiwan, he had effectively created a school of civil engineering (especially sanitation engineering) that was unique to Japanese society. Although his “school” was not an official academic institution, Burton had cultivated a broad network of practitioners who were greatly influenced by his methods and principles. This generation of engineers – all of whom largely followed Burton’s unconventional and innovative approaches – was responsible for transforming Japanese Formosa by controlling its water. Although Burton died in 1899, his students carried on his work and continued building Japan’s water technology in Taiwan. In 1908, Taipei’s first water treatment facility was completed, housed in an Imperial Crown-style building consistent with Neoclassical design principles of Meiji Japan.

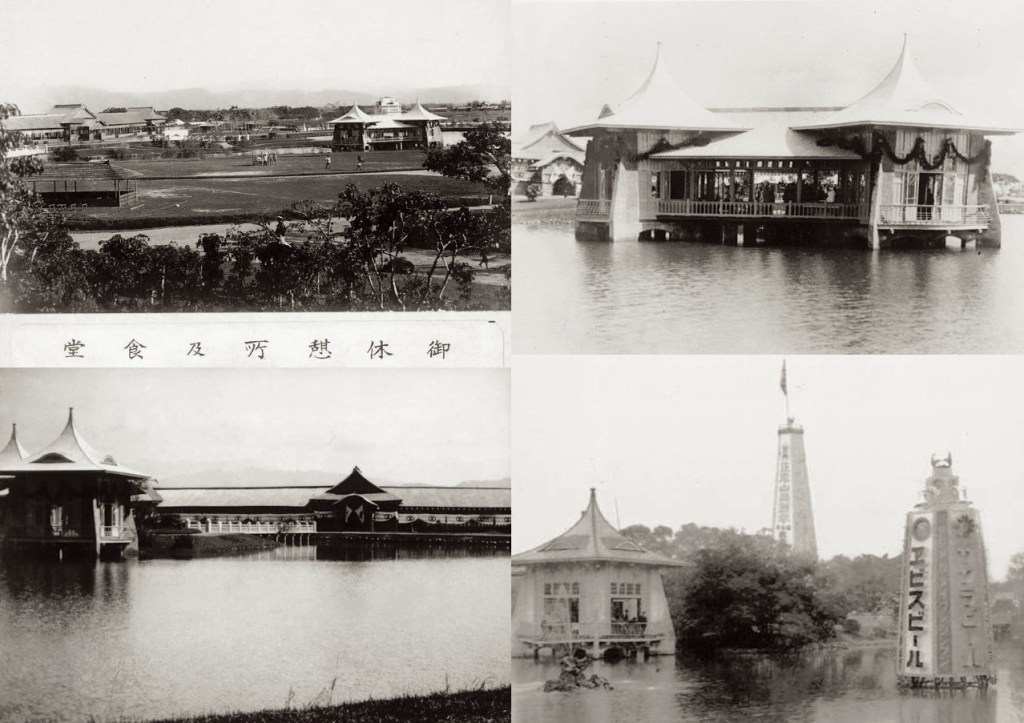

The reformation and stabilization of Taipei set the tone for the rest of the island. The water masters looked southward to what would become the third largest city, Taichung (about 82 miles south of Taipei), designated and nicknamed “Little Kyoto” with the intention to evoke the namesake’s waterways and landscaping. Kyoto, which had been the capital of Japan for over a millennium until 1868, was the model blend of urban development in harmony with nature. Its city planning integrated natural features such as rivers, gardens, and mountains with architectural structures – all highly engineered to present a balanced and aesthetically pleasing environment. The use of a grid pattern in Taichung was not only practical for organizing space, it was a deliberate nod to Kyoto’s naturalistic approach to city design that emphasized symmetry and connectivity. As the centrally located city (built to be a cultural capital for the island) – and the final meeting point where the north-south rail system would join – not far from Taichung station was to be Taichung Park. This park was completely man-made to look natural and pre-existing (it was meant to be a Shinto forest), and in the center would be a lake – the center of the lake would be a pavilion, eventually a symbol for Taichung.

The empire’s intention for central Taiwan was somewhat at odds with its original, natural state. Taichung sits in a mountain basin, which might forecast drainage issues for the typhoon-prone subtropical island. However, the surrounding mountains function to break up typhoons and Taichung is rarely severely affected by typhoons in the first place. An added insurance policy is the canal system that Japanese water engineers aggressively developed throughout the island. Even when a typhoon dumps half the ocean onto the city, the water is carried back into the ocean by the canals.

The challenge posed by the mountains – for they serve as a double-edged sword – is that the terrain causes inland pockets that have no reliable access to water. Taiwan’s topography, with its steep, rugged mountains that cover much of the island’s central and eastern regions, creates natural barriers between the coastal plains and the interior. These mountains make it difficult for water to naturally flow into the inland agricultural areas, limiting access to water in rural zones. To conquer the mountainous terrain that runs north-south of the island, man-made tributary and inverted siphon technology (the Baileng Canal) was perfected to ensure the water supply could reach the rural communities as populations exploded in urban areas. An example of this problem is the Shinshe plateau, just outside Taichung. Once an arid food desert, the development of advanced water management systems was crucial to transform the area into a fertile land capable of supporting Taiwan’s agricultural boom. Today, Shinshe is considered “Taichung’s back garden” and the fruit basket for the island.

By 1920, imperial Japan’s colonial experiment via water engineering reached its zenith with the completion of the Wushantou Dam. Civil engineer Yoichi Hatta was entrusted with the monumental task of transforming the barren Tainan Plain in southern Taiwan into a fertile agricultural heartland. A graduate of the prestigious University of Tokyo, one of the leading institutions for engineering in Japan, Hatta had honed his expertise in irrigation and hydraulic engineering by working on large-scale infrastructure projects throughout the country. His technical prowess, combined with a deep understanding of Taiwan’s geography and the need for efficient water management, made him the perfect candidate for the project. More than his technical skills, it was Hatta’s vision of reshaping Taiwan’s landscape into an agricultural powerhouse that ultimately secured his role – success would not only elevate Taiwan’s role in Japan’s empire but also cement his legacy as a national hero. Over the next decade, Hatta meticulously designed and built an extensive network of canals, culminating in the completion of the island’s first dam. The Wushantou Dam, which transformed southern Taiwan into its agricultural engine, was a feat of engineering on a scale reiterating the central island’s inverted siphon – only on a far grander scale. [3]

In just a few decades, Japanese colonists used their water management skills to wrest a subtropical island from its untamed state to an efficient modern system of cities – all feeding into the imperial machine that benefited greatly from the efficient upgrades to a natural resource supply chain. The majority of colonial Japan’s water engineering facilities still exist and are still in use, some 100+ years after construction was first completed. While metropolitan areas expanded and outgrew some of the original structures, relics of the Japanese legacy also continue to exist – even after a period of post-WWII Chinese martial law that heavily discounted Japanese colonial achievements. From north to south, these achievements have had other impacts on socio-economic and cultural landscapes of Taiwan, particularly in the 21st century:

- The 1908 water treatment facility in Taipei was converted into the Museum of Drinking Water (and theme park), and although no longer in operation, the original equipment has been preserved, along with official documents describing colonial Japan’s water policy. The building is now a popular backdrop for engagement and wedding photos.

- Taichung Park, famous for its man-made lake, was the celebration grounds when the Japanese rail system was completed in 1908 all for a visiting Japanese prince who was also on a mission to make Shinto a state religion for Taiwan.

- The canal and inverted siphon of central Taiwan townships received extra attention in 2013 when the descendants of the Japanese-era engineer were invited to take part in a statue unveiling ceremony celebrating the achievement. A former Taiwanese ambassador to Japan (whose retirement residence was in Taichung) would always take Japanese visitors (often on unofficial diplomatic visits) to see the Baileng Canal No. 2 pipe.

- The Wushantou Dam has become a research focus of a Japanese professor teaching political science at a university in southern Taiwan, emphasizing the effects of warring nations and how one man can go from being a servant of an enemy culture to being deified as a cultural hero. [4] Annual celebrations (as well as milestone celebrations) of this construction marvel often attract tourists of all levels: casual domestic day trippers to high profile government officials (including presidents) as well as Japanese tourists who have formed diplomatic societies that involve planting cherry trees on the grounds as a symbol of the unique Taiwan-Japan alliance.

It was no accident (or coincidence) that the cities – Taipei (台北), Taichung (台中), and Tainan (台南) – all have strategic names: North (北), Central (中), and South (南) cities of the Taiwan (台灣) “platform bay” island. If architecture, according to Vitruvius, is about a collection of structures that is really about the building of a city, then these cities were leading up to an empire.

The legacy of Japanese water engineering has had a rather bipolar reception since the colonists left Taiwan. Having been on the losing side of the war, Japan had to give up its model colony because it had been promised to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek of the Chinese Nationalist Army (who was on the losing side of the Chinese civil war against Communist forces). Although the Nationalists had ironically once been allied with Japan during the Chinese civil war against the Qing dynasty, the Nationalist martial law period in Taiwan that followed World War II saw a strong anti-Japan public sentiment that resulted in the Japanese colonial infrastructure being overlooked for its significance. Like a ball in a high-stakes game, Taiwan’s fate was and continues to be determined by the force and direction of competing forces, each leaving their mark as they vie for dominance over the island’s future. Appreciation for catapulting the once-backwater island into modernity was downplayed as the Japanese were the antagonists and oppressors of the story that the Nationalist Party told – that is, until the 2000 Taiwan presidential election that installed the opposition party that turned the tide and started the currents that flows into the pro-Japanese Taiwan of today. But tides can change, even as infrastructure remains the same. [5]

Emi Higashiyama lived in 1980s Taiwan when it was under martial law. She later attended the Lee Teng-hui Academy in 2010 when it resurrected its Leadership Institute Program in National Policy Studies, on recommendation from Koh Se-kai (former Taiwanese ambassador to Japan in the mid-2000s).

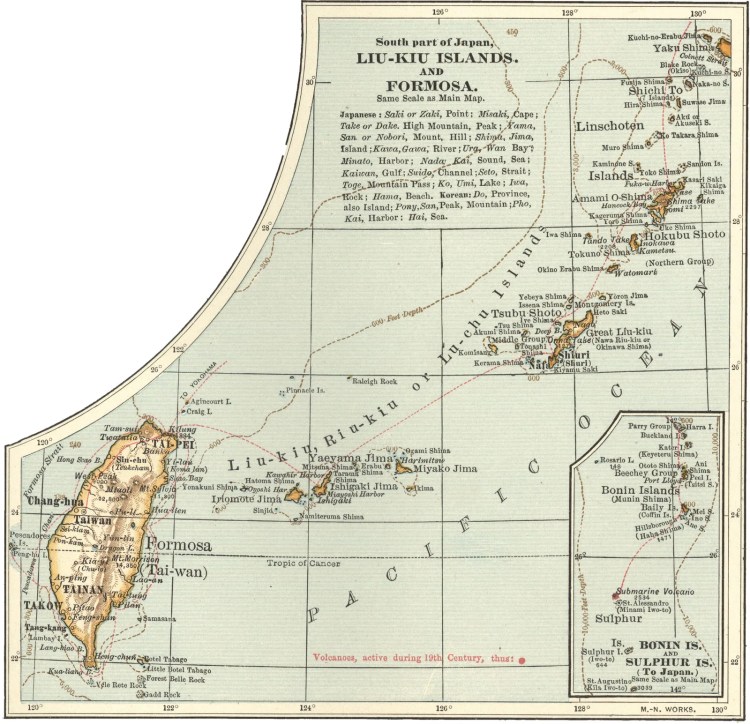

Featured image (at top): Map of Taiwan and Ryuku Islands from 10th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica, 1902.

[1] Ashoka Mody, ed., Infrastructure Strategies in East Asia: The Untold Story (World Bank, 1997).

[2] Chia-Jung Wu and Jinn-Guey Lay, “Beyond technology: Japanese colonial mapping of water estates in Taiwan from 1901 to 1921,” International Journal of Cartography 1, no. 1 (2015): 94-108, doi: 10.1080/23729333.2015.1055647

[3] C.H. Wang, “Using Remote Sensing Technology on the Delimitation of the Conservation Area for the Jianan Irrigation System Cultural Landscape,” International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XL-5 no. 5 (2015): 443-448.

[4] Yoshihisa Amae, “A Japanese engineer who became a Taiwanese deity: Postcolonial representations of Hatta Yoichi,” East Asian Journal of Popular Culture 1, no. 1 (2015): 33-51, doi: 10.1386/eapc.1.1.33_1

[5] John Hitchcock Hayashi, Hydraulic Taiwan: Colonial Conservation under Japanese Imperial and Chinese Nationalist Rule, 1895-1964 (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2023).