Editor’s note: This is the second post in our theme for November, The Latinx City.

By Andres Villatoro

A friend from graduate school recently visited Chicago for the first time ever to present at a large annual academic conference. As an international student from Santiago, Chile and a lover of cities, I was excited for her to see the city that birthed my own love for urbanism and that I grew to love and call home for six years, before I moved to Philadelphia for graduate school. I was most excited for her to see how “Latino” Chicago was. After living in Philadelphia for close to two years, my return to Chicago delivered a welcome shock of “brownness.” Compared to Philly, Latino Chicago felt massive, complex, and established. My friend noted this too. After directing her to Pilsen, a prominent Mexican neighborhood on the city’s near Southwest Side, she remarked that Pilsen in particular felt different than the number of Latino immigrant neighborhoods she had encountered so far in the United States. Notably, Pilsen did not feel disinvested or neglected. “I realized that it felt like I was in a hip neighborhood in Santiago.” She told me. The neighborhood felt alive, trendy, and most importantly, unapologetically Latino.

I have been reflecting on her own theorization of Pilsen since I moved back to Chicago in order to collect data for my dissertation on native-born Latino men in the city. Her comparison with similar neighborhoods in Latin America was thought-provoking, offering a fresh perspective I hadn’t encountered despite having lived in Chicago for several years before graduate school. Of course, the prevailing explanation among socially conscious Chicagoans for the neighborhood’s current state is gentrification. Pilsen, a predominately working-class Mexican neighborhood in the 1980s and 1980s, has undoubtedly undergone change due to gentrifying forces.[1] Rising rent and home prices, an influx of college educated and white residents, and the pop-up trendy restaurants and art galleries all indicate clear signs of displacement.[2] What I think is happening there, however is different.

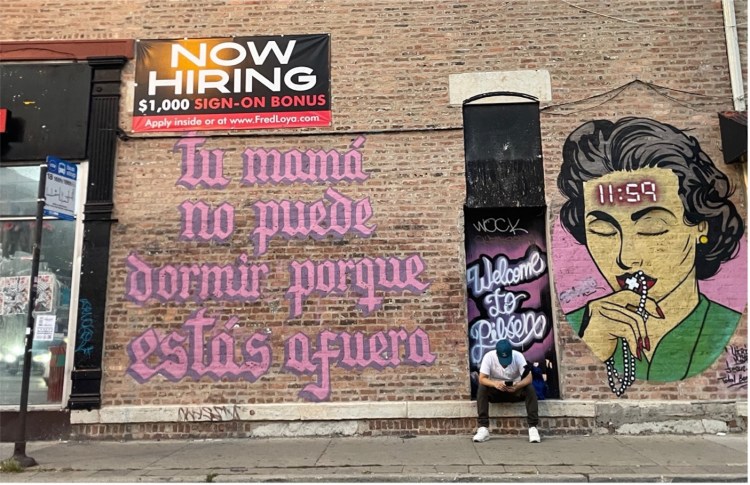

While housing and rent prices have continued to rise, over the past few yeas there are signs that gentrification and certain forms of displacement in the neighborhood have decelerated.[3] Crucially, the area has not experienced rapid cultural displacement. Evident in street murals, trendy restaurants, or boutique shops, Pilsen remains defiantly Latino‚ specifically Mexican American. Indeed, I argue that it has become a cultural center, not for Chicago’s large Mexican immigrant population, but for their children.

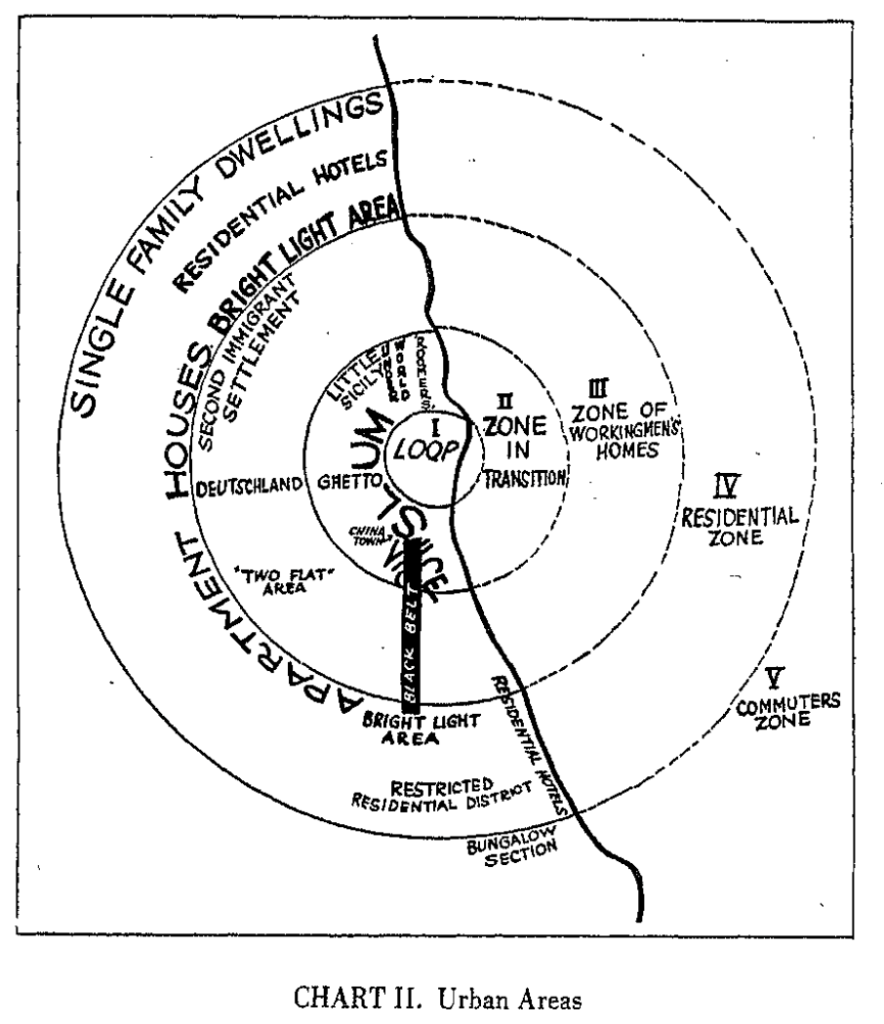

While Mexican Chicago generally adheres to historical patterns of immigrant settlement and assimilation in the city, the contemporary reality presents some fascinating departures from these theories. In the early 20th century, classical urban sociologists associated with the University of Chicago and the Chicago School of Sociology theorized immigrant spatial assimilation, positing that as immigrants integrate into society, they tend to move from inner-city ethnic enclaves to more affluent suburban areas.[4] This outward movement is seen not only as a sign of upward social mobility and acculturation but historically was also associated with assimilation into whiteness. Italian immigrants in Chicago, for example, initially settled in the Near West Side’s “Little Italy” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. With economic mobility and integration came movement to peripheral city neighborhoods like Elmwood Park and Melrose Park, and later to suburbs such as Addison and Bloomingdale. Polish, Greek, Irish, and countless other white immigrant groups roughly followed these spatial assimilation trends, not just in Chicago but in Northern cities throughout the U.S. Though not initially viewed as white, by the mid-twentieth century their assimilation into whiteness was also largely successful.[5]

In significant ways, Mexican Chicago fits the historical spatial assimilation model. Historically concentrated on the city’s Southwest Side, Mexican immigrants in Chicago initially settled in working-class industrial neighborhoods near the city’s downtown “Loop,” such as South Chicago, Back of the Yards, and Pilsen, starting in the early 20th century. As the model predicts, population growth and economic stability or mobility led Mexican Americans to move further out to areas like Little Village (La Villita), and today, to neighborhoods in the city’s periphery such as Gage Park or West Lawn and nearby suburbs like Cicero and Berwyn, some of the most heavily Mexican areas of the city.[6] Additionally, numerous second, third, or even fourth-generation families of Mexican descent can be found in Chicago’s more affluent outer suburbs.[7]

Today, however, the Mexican American urban spatial settlement pattern diverges in two important ways. First, specific suburbs in Chicago are now becoming the new destination for recently arrived immigrants, whether Mexican or other Latin American, completely bypassing the city neighborhoods altogether.[8] Second, the second generation (or third/fourth generation) has not necessarily abandoned their parents’ or grandparents’ neighborhoods for the greener pastures of the suburbs.

Instead, I’m finding that the second generation is claiming urban space within the city in clear but underexamined ways. In fact, in a city where immigrants have been heavily studied since the turn of the 20th century, theories on the presence of second and subsequent generations of immigrants are few and far between. The assumption has primarily been that they move away from the city and assimilate, making room for new waves of immigrants. The Mexican second generation (and other Latino groups in Chicago), however, may be disrupting this pattern. Their claim to urban space, previously unrecognized particularly in historical immigrant neighborhoods of their parents and grandparents, can be described as novel.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Pilsen. Walking down 18th Street, the neighborhood’s main thoroughfare, one is immersed in Mexican and unapologetically Latino cultural symbols and spaces. The neighborhood’s countless murals depicting Selena, immigrant rights, and general Latino art blend seamlessly with numerous Mexican-themed restaurants, coffee shops, vintage clothing and furniture stores, and galleries. While several of these symbols and spaces are present in Chicago’s other growing Latino neighborhoods, the difference is that Pilsen has largely ceased to be an immigrant neighborhood. Indeed. these businesses and spaces are not necessarily targeted toward newly arrived migrants. Instead, what we are witnessing in Pilsen is a neighborhood for second generation, a space where their culture and experiences are reflected back at them, whether in art or in retail.

The gentrification of the neighborhood has certainly facilitated the birth and maturation of the second-generation presence in Pilsen. However, common narratives of white-led gentrification and displacement in the neighborhood oversimplify matters which requires greater nuance to understand how the second generation lays claim to Pilsen and other neighborhoods around the city.

Part of this story is residential. The neighborhood is undoubtedly experiencing “gente-fication,” a term coined to explain the influx of mostly college-educated and young Latino residents moving into previously Latino immigrant neighborhoods to take advantage of both the cultural resources and affordable rents.[9] Another aspect is that while the number of white residents has increased in the neighborhood and working class families are being displaced, the clientele in the area’s businesses and spaces continues to be overwhelmingly Latino. In fact, while most second or third-generation young people may continue to live in the outskirts of the city or suburbs, following traditional spatial assimilation models, Pilsen continues to be a significant cultural meeting point for these groups. Whether patronizing landmark bars, restaurants, nightclubs, or attending the numerous Mexican street festivals that Pilsen hosts throughout the summer, one can find large crowds of predominantly U.S.-born Latinos eating, dancing, and purchasing. As I am currently discovering during my year of ethnographic fieldwork, the second generation gravitates toward these spaces in the city, frequenting the same bars and restaurants‚ places that, while different from locales favored by their parents, reflect and reaffirm their ethnic identity.

Chicago is not unique in the spatial presence of its second generation. Undoubtedly, cities with decades of Latin American immigration have begun to see spaces tailored to the second generation, in Los Angeles, New York, and large Latino cities in Texas, but these spaces continue to be understudied. Nor is Pilsen the only center of second-generation presence in Chicago. While it may be where the Mexican second-generation concentrates, there are countless bars, restaurants, and even concert venues where U.S.-born Latino culture is dominant. I recently discovered the history of Chicago’s Latino punk scene, dominated by local venues and house shows in neighborhoods like Pilsen, Little Village, McKinley Park, and Bridgeport. At a recent art exhibit and community conversation I attended, U.S.-born Latinos discussed their desire to rebel against their parents’ culture while also wanting to see punk artists and bands that looked like them. The house shows, which once predominated the Latino punk scene, often made a loud presence in the neighborhoods on weekend nights, frequently drawing criticism from neighbors. However, as one attendee noted, if their immigrant neighbors could play rancheras and other loud Spanish music until 3 a.m. on warm summer nights, why couldn’t they play punk rock?

As the Latino population grows throughout the United States, Latinidad will only become more central to the American urban cultural scene, as scholars have pointed to in the past.[10]

Of course, waves of new immigrants will continue to contribute and add new dynamics to these urban cultures. However, the presence of the second generation (and third/fourth generation) and their claim to urban space will also play a significant role in the Latin Americanization of our cities, especially as this is the fastest-growing Latino group in a city like Chicago.[11] What will it mean to have more spaces and neighborhoods that are Latino but native born? Perhaps there will be some similarities or solidarities with sister neighborhoods in Latin America, such as Roma or Condesa in Mexico City, Barrio Franklin in Santiago, or San Telmo in Buenos Aires.

How the second generation will continue to transform urban space will be significant if assimilation into “whiteness” does not occur in a straight line for second or third-generation Latinos as it did with previous European immigrants and their descendants. If anything, a substantial portion of the second generation may find their identities more closely tied to their cities than to their parents’ culture or U.S. culture at large, as one of my participants recently explained: “I don’t even see myself being from the Midwest or anything; I’m a Chicago American.”

Andres Villatoro is a PhD Candidate in the department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. His broader research interests lie in the areas of Urban and Neighborhood Sociology, Social Class and Inequality, and the Labor Market. He is currently living in Chicago, where he is completing ethnographic work on native-born U.S. Latino men and their experiences with the labor market.

Featured image (at top): Mural on 18th Street and Ashland. Public Art in Pilsen is also often targeted toward the second generation. Here the mural reads, “You’re mother cannot sleep because you are are out.”

[1] Mike Amezcua, Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to Gentrification (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023).

[2] John J. Betancur and Alexander Linares. Who Lives in Pilsen: The Trajectory of Gentrification from 2000-2020. (Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute, 2023). https://greatcities.uic.edu/2023/05/15/report-release-who-lives-in-pilsen-the-trajectory-of-gentrification-from-2000-to-2020/.

[3] Stephanie Lulay, “Pilsen Gets Whiter As 10,000 Hispanics, Families Move Out, Study Finds.”. DNAInfo Chicago, April 13, 2016. https://www.dnainfo.com/chicago/20160413/pilsen/pilsen-gets-whiter-as-10000-hispanics-families-move-out-study-finds.

[4] Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess, The City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925)

[5] Joel Perlmann, Italians Then, Mexicans Now: The Second Generation (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004)

[6] Amezcua, Making Mexican Chicago.

[7] Following sociological immigration literature, i write about immigrant generations, not American generations so that first generation immigrants are those that immigrated to the United States and Second-generation immigrants are their children and so forth.

[8] Karyn Lacy. “The New Sociology of Suburbs: A Research Agenda for Analysis of Emerging Trends.” Annual Review of Sociology 42, no. 1 (2016): 369–84.

[9] Soni Sangha. “In Taking Back Urban Areas, Latinos Are Causing A ‘Gente-Fication’ Across The U.S.,” February 7, 2014. https://www.foxnews.com/lifestyle/in-taking-back-urban-areas-latinos-are-causing-a-gente-fication-across-the-u-s.

[10] Mike Davis, Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the US City. (Verso Books, 2024).

[11] Amy Qin, “New Census Data Finds 1 in Every 5 Chicagoans Identifies as Mexican.” WBEZ Chicago, September 24, 2023. https://www.wbez.org/stories/1-in-5-chicagoans-identify-as-mexican-census-data-show/bd5f5c57-0386-4020-a037-1292270a59b3

A thoughtful and important discussion. I would add two influential books for understanding these neighborhoods and their residents over time: Deborah E. Kanter, Chicago Catolico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican (Illinois, 2020) and Lilia Fernández, Brown in the Windy City: Mexican and Puerto Ricans in Postwar Chicago (Chicago, 2012).

LikeLike