This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Bridget Kelly

What makes a site special? What must happen there for society to decide that a place, a building, a history is worth preserving?

In 1991, the New York City Landmark Preservations Committee (LPC) considered these questions when determining whether or not Harlem’s Renaissance Theater and Ballroom Casino deserved such recognition.

Howard University alum Helen Brown moved to Harlem in 1923, one year after the Renaissance’s grand opening, and shared her memories:

“And the Saturday night rent parties and they’d have the grandest time at the Renaissance Ballroom, and you know young people could dance all night and never get tired. You know what that meant? That meant that they would relax in their muscles, and they didn’t have to go to the psychiatrist.”[1]

Rent parties emerged in Harlem during the Roaring Twenties. Brown fondly recalled attending these events at the “Ren” where people danced, sang along to the music, and pooled their funds together to aid their neighbors. In her mind, these rent parties functioned as creative outlets in which people could unburden themselves.

The Renaissance served multiple purposes at a time when entertainment spaces, even in America’s most famous Black neighborhood, closed their doors to Black clientele. In addition to rent parties, the Renaissance hosted film screenings starring “all Negro casts,” professional basketball games, and used the space for political activism.[2] The NAACP held anti-lynching meetings on the same court where the Big-Five wowed the crowd.[3] This combination of athletics, art, and activism made Harlem one of the world’s most dynamic entertainment and political centers. People would travel great distances to see the Rens play and would rush the court to dance on the same floor following the final whistle. The Renaissance Theater and Ballroom/Casino quickly became Harlem’s home court and, like most home courts, you must defend it.

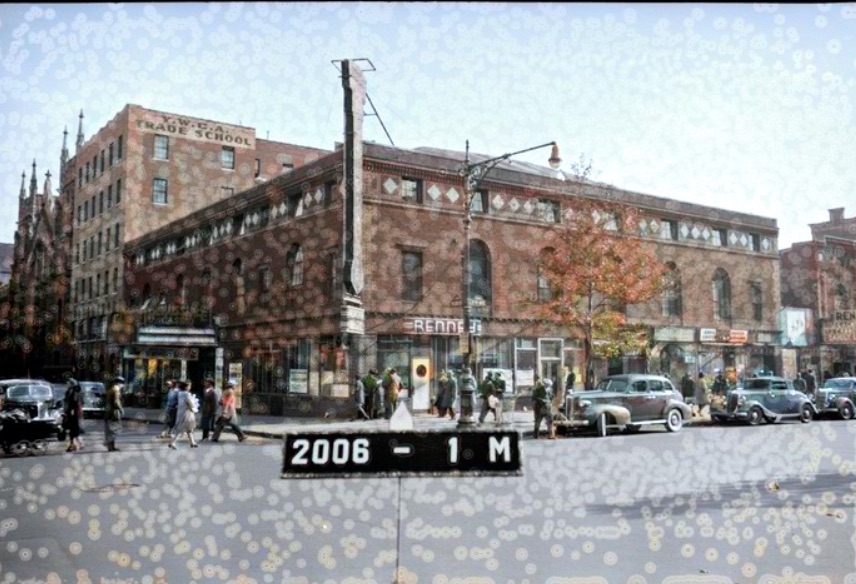

Unlike every other Harlem hot spot, the Renaissance was owned and operated exclusively by African American proprietors. The Harlem Community Enterprises Corporation commissioned African American architect Vertner W. Tandy to design an open-air motion picture theater, and he began drawing up plans in August of 1920.[4] Architect Harry Creighton Ingalls joined the project and designed the Renaissance Theater to exhibit thirteenth and fourteenth-century North African Islamic architecture.[5] Adorned with terra-cotta decorations, these façades contained dark red brickwork with “contrasting muquarnas cornice frieze panels of glazed polychrome tiles,” reflective of Moorish architecture principles.[6] Ingalls’s creative use of brick “not just for construction but also for decoration, in conjunction with ceramic tile, was particularly characteristic” of North African architecture. Ingalls integrated four-tile, glazed-ceramic, pale blue plaques to create a contrast against the dark red brick, creating a structure that highlighted Harlem’s connection to Ethiopia.[7]

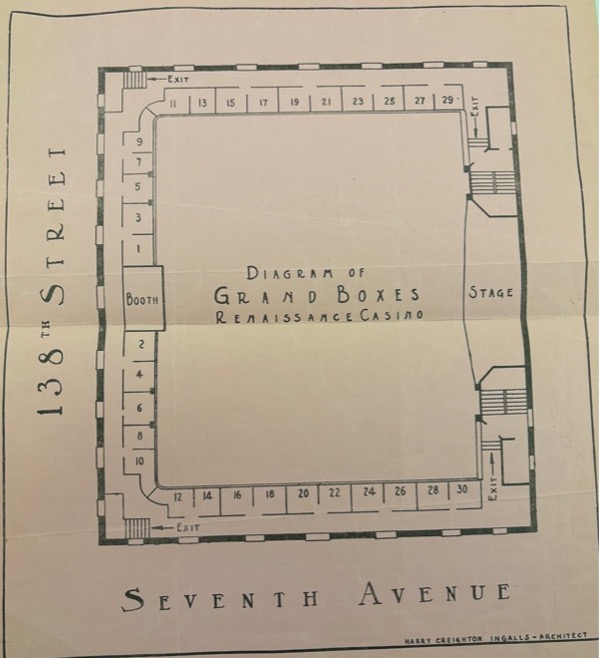

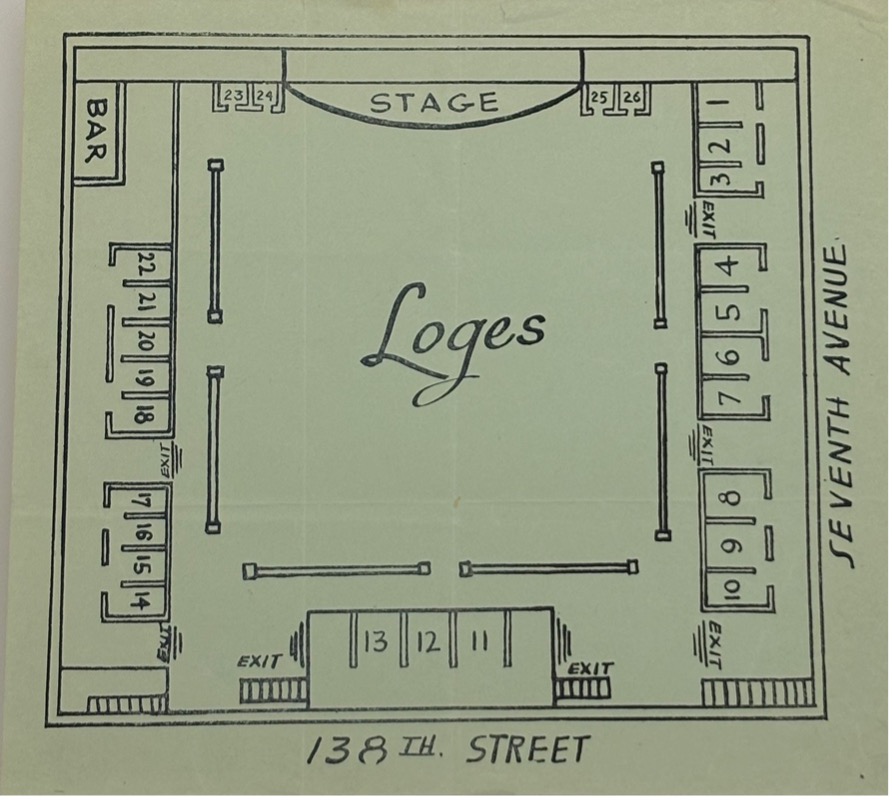

The Renaissance consisted of two separate buildings, the Ballroom and the Theater, that extended the entire block between 137th and 138th Streets along Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard (Seventh Avenue). Ingalls designed the Renaissance Theater at a moment when architects such as Thomas Lamb had just begun developing the motion picture theater as a distinct “building type.”[8] Ingalls reserved the building’s Seventh Avenue façade for storefronts and the theater’s main entrance.

For fifty years, this two-story structure functioned as a multi-use facility that hosted family activities on the first floor and casino and dancing businesses upstairs. At full capacity, the Renaissance hosted 1,192 people.[9] Like the Renaissance Theater, Black-owned businesses exclusively rented storefronts surrounding the Ballroom/Casino. William Roach, an immigrant from the Caribbean Island of Montserrat and Sarco Realty president, placed an advertisement in New York Age urging Black New Yorkers to support Black businesses.[10] Popular Black newspaper Amsterdam News described the Renaissance as “something never before seen in Harlem” and “the most beautiful and handsome place of its kind in New York City for our people.”[11]

During the Roaring Twenties, white New Yorkers continued to visit exclusive, reservation-only spots, such as the Cotton Club, Small’s Paradise, and Connie’s Inn, whereas Black Harlemites took advantage of the Renaissance’s open-door policy. The Renaissance continued to host community rent parties headlined by Fletcher Henderson, known by music historians as “the progenitor of swing music.”[12] Clyde Bernhardt, another musical legend, reverently reflected on his trombone-playing days at the Renaissance and said, “the place was the most famous ballroom in Harlem, at one time more popular for big name society dances than the Savoy.”[13] By the 1930s, however, as the Great Depression clutched the nation, Black businesses in Harlem especially suffered. Roach lost ownership of the Renaissance, and Black business occupancy rates dwindled.[14]

By 1940, Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay concluded, “there is not a Negro-owned dancing hall in Harlem.”[15] The Renaissance remained popular but lost its defining character; no longer Black-owned, the Renaissance shifted from a democratic public-use model that elevated community needs to a business sustained by private rental agreements, such as weddings, proms, and banquets “that promoted their own affairs.”[16] The all-night community rent parties Helen Brown affectionately remembered were a thing of the past. Black Harlemites lost the space that allowed them to “relax in their muscles.”[17]

The building sat vacant beginning in the late 1970s and closed three years after New York City declared bankruptcy. By 1990, all street-level stores had been boarded up and sealed. Spike Lee used the abandoned site as a “crack den” location in his film, Jungle Fever.[18] It was around this time that Helen Brown shared her oral history with a philosophy class at La Guardia Community College. The following summer, on July 15, 1991, the LPC held a public hearing on the proposed landmark designation. Two years into the historic preservation committee’s investigation, the Renaissance Complex Redevelopment Corporation (RCRC), a for-profit group formed by eight Harlem businesspeople, and the Abyssinian Development Corporation (ADC) bought the building’s mortgage in foreclosure court.[19]

In the spring of 1997, the LPC found that “the Renaissance Theater and Ballroom/Casino has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City.”

Was it the alfiz motif on the building’s squat towers, or the regularly placed elements along the frieze and cornice levels? Or more likely, the NAACP chapter meetings held here, the world champion basketball team, and the history of Black ownership persuaded the commission. Perhaps it was the way Harlem integrated charity with camaraderie and made the Renaissance a community resource and bedrock to build neighborhood connections where people could dance and receive a helping hand, which Helen Brown light-heartedly suggested kept Harlem from going crazy.

To make something “historic” as the LPC did with the Renaissance requires an admission that a site is especially important and worth preserving. The LPC defines their work as identifying and protecting New York City’s sites of “significance.”[20] The municipal body “works to ensure that owners of designated properties comply with the Landmarks Law,” which require special city permits before making any changes.[21] Since its creation in 1965, the LPC has designated over 38,000 buildings and sites.

Did the designation maintain the Renaissance’s core character, one that centered community needs without exorbitant entrance barriers? Has the landmark classification maintained a connection to the Ren’s past?

Today, the historic landmark operates as “the Rennie,” luxury condominiums. The RCRC split the dance floor and basketball court and constructed 134 high-end housing units. Homes that go for a minimum of a half a million dollars have replaced the Renaissance rent parties.

The Rennie’s marketing team boasts how the condo-complex gives “new meaning to city living in the heart of Harlem.”[22] The former Renaissance’s version of city living fostered human connection and made Black ownership and use priorities. Today, however, “city living in the Harlem of heart” is financed by Goldman Sachs and twenty-five-year tax abatements, lost property taxes that would otherwise go to schools and other public institutions that benefit the community.[23] The Renaissance, formerly known as Harlem’s home court, needs a new defense scheme.

Featured image (at top): The site in 2024. Photograph by Jacob Jordan, Esq. on June 29, 2024.

Bridget Laramie Kelly is a fifth-year PhD candidate in international urban history at Washington University in St. Louis. Her dissertation, “The Harlem Uprising of 1943: Black Self-Determination and the Formation of Probationary Citizenship,” develops a new framework for understanding what previous historians have considered a “riot,” and instead interprets the event as a pivotal wartime demonstration in America’s largest Black city in relation to New York City’s innovative use of probation. Her work has been funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, University of Virginia, and George Mason University. Kelly has a forthcoming article titled: “’I Get So Mad Cause We Ain’t Got No Freedom’: Black Women, Rage, and the Harlem Uprising of 1943” in the Journal of Urban History and a book review for the Journal of Social History for Stephen Robertson’s Harlem in Disorder: A Spatial History of How Racial Violence Changed in 1935 coming soon.

[1] “Helen Brown, Harlem Resident, Talks About Her Eyewitness Account of 1943 Harlem Riots,” The La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York. La Guardia Video Collection – ID # 01.001.V22.

[2] “The Renaissance continues to show the best pictures and is taking its place as one of the favorite movie houses in Harlem.” Oscar Micheaux directed movies with “all black casts” which were “a mainstay of the Renaissance Theater during the 1920s-40s.” Source: Landmarks Preservation Commission Draft (December 30, 1994), Report of the New York Landmarks Conservation Commission from Renaissance Ballroom and Theater Complex History, 1, 13. William Miles Collection at Washington University in St. Louis Box: R1650822 (F253-1). [henceforth referenced as Landmark Preservation Proposal].

[3] Christopher Gray, “A Harlem Landmark in All but Name,” The New York Times, Feb. 18, 2007; The Rens defeated the Boston Celtics to win the first world championship tournament for professional basketball in 1939.

[4] Known as the “first lady of blues,” Mamie Smith’s open air moving picture theater, called Garden of Joy, stood at 99 by 100 feet. See: Frank Tirro, Jazz: A History (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1977), 139. In 1921 a German immigrant, Caroline Bird, purchased the theater building and shortly thereafter sold the property to the Sarco Realty Holding Company, Inc. Sarco filed an application for an alteration permit on March 28, 1922. Landmark Preservation Proposal, 12.

[5] The Sarco Realty & Holding Company purchased the location from the estate of Curtis B. Pierce on February 6, 1920. “The initial new building application, filed in June 1920, projected a four-story theater, penthouse, and roof garden. In August the architect withdrew the application in favor of a second, less ambitious” two-story building. Landmark Preservation Proposal, 3, 11. Roach worked with other Black entrepreneurs such as Joseph H. Sweeney and Cleophus Charity.

[6] Landmark Preservation Proposal, 4-5.

[7] “Raised brick, diagonal bonds, vertical and horizontal bonds, and raked joints are elements of what scholars of Islamic architecture have called the ‘naked brickwork style.’” Landmark Preservation Proposal, 5.

[8] Thomas Lamb designed Harlem’s Regent Theater in 1912-13, which also received historical landmark designation. The Regent Theater is now used by the First Corinthian Baptist Church; in 1919 Edwin H. Flagg described motion picture theater (also known as presentation houses) design principles as “still in an experimental stage.” Edwin H. Flagg, “Evolution of Architectural and Other Features of Moving Picture Theatres,” Architect and Engineer 57 (May 1919), 97-102.

[9] The ballroom seated 700 and the theater had 492 seats.

[10] Full quote: “In this big city, every known group of White businessmen are affiliated with some organization for the development of his business interest…it should and must be for the same reason that we Colored men in business will have to organize more efficiently than we have in the past.” “To Colored Men in Business,” New York Age, April 2, 1921.

[11] Full quote: “The main floor of this building will be occupied by colored businesses exclusively, and the other floor will be used as a hall for entertainments, dances and basketball.” Amsterdam News, December 20, 1922.

[12] Duke Ellington described Fletcher as a major influence on his music: “His was the band I always wanted mine to sound like.” See: Edward Kennedy Ellington, Music Is My Mistress (New York: Doubleday and Co., 1973).

[13] Clyde Bernhardt, I Remember, Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands, and the Blues (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986), 117.

[14] In 1934, Bertbar Realty purchased the Renaissance Theater [Block 2006, Lot 1] and the Renaissance Casino [Block 2006, Lot 61].

[15] Claude McKay, Harlem: Negro Metropolis (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1940), 118.

[16] “With a house band no longer employed, most organizations simply rented the hall, hired a band, and promoted their own affairs.” Landmark Preservation Proposal, 7.

[17] The La Guardia and Wagner Archives, La Guardia Community College/The City University of New York. La Guardia Video Collection – ID # 01.001.V22.

[18] Production designer Wynn Thomas recalled their decision to film the climactic scene at the Renaissance: “You could feel the ghosts. You could feel the greatness of the place that is the symbol of the great Harlem Renaissance.” Landmark Preservation Proposal, 8.

[19] The Abyssinian Development Group would later lobby the Landmark Preservation Commission to retract the designation when they realized a landmark status interfered with their redevelopment plans to turn the historic site into luxury condominiums. See: “Future of historic Harlem ballroom debated,” New York City Land Use News and Legal Research, February, 15, 2007.

[20] “About LPC,” Landmarks Preservation Commission, https://www.nyc.gov/site/lpc/about/about-lpc.page.

[21] “Violations,” Landmarks Preservation Commission, https://www.nyc.gov/site/lpc/violations/violations.page.

[22] The Rennie, https://therennie.com/.

[23] John Jordan, “The Rennie Condo Building in Harlem Secures $71M in Financing,” Globest (November 28, 2028).