This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Weilan Ge

American ecologist Loren Eiseley once said, “If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in the water.”[1] The National Aquarium in Baltimore (NAIB) puts this message at the entrance for all visitors to see, illustrating that it tries to “connect people with nature to inspire compassion and care for our ocean planet.”[2] Baltimore’s politicians established the National Aquarium to serve the urban renewal strategy of “Returning Baltimore to the Sea,” harnessing the resources of the ocean through science and environmentalism to help Baltimore mowve from heavy industry to tourism.[3] In the early days of the twenty-first century, the marine crisis has become one of the biggest threats to the sustainable development of Baltimore. Therefore, Baltimoreans have begun to reintroduce the marine ecosystem into the Inner Harbor, shrink the scope of urban expansion, and readjust the boundary between cities and oceans. At the same time, facing new expectations from environmentalism, marine conservation, and the animal rights movement, the National Aquarium has begun to transform itself through an effort to take on more environmental responsibility and expand conservation beyond its tanks to the vast Chesapeake Bay. The aquarium has become an important part of Baltimore’s protection of the marine environment and plays an important role in public education, marine conservation, animal rescue, and scientific research.

As current aquarium CEO John Racanelli put it, unlike other aquariums funded largely by “billionaire donors” in the private sector, the National Aquarium “was built by the grit and determination of an enterprising city and its taxpayers.”[4] William Donald Shaffer (the forty-fifth mayor of Baltimore), Martin Millspaugh (Charles Center-Inner Harbor CEO), and Robert Embry (commissioner of the Department of Housing and Community Development for Baltimore City) played important roles in establishing the aquarium. In 1973, Robert Embry persuaded Mayor Schaffer to visit the New England Aquarium in Boston, which inspired them to build an aquarium in the Inner Harbor and make it a world-class attraction that attracts people to the downtown and drives tourism. Baltimore is no stranger to aquariums in its history, with the first aquarium located in Druid Hill Park, which opened in 1938 and was a source of pride for the city at the time. Unfortunately, the aquarium was forced to close in 1943.[5]

A few decades later, urban elites decided to build a new aquarium with a larger area, a wider variety of marine life, a more advanced infrastructure, and in keeping with the trends of marine science and public education. They believed the aquarium would be a key part of rebuilding the Inner Harbor and helping Baltimore rebuild its image as a city. In 1976, the Maryland General Assembly authorized the city of Baltimore to initiate a bond referendum, and residents voted to approve a bill to raise money for a new aquarium. [6]

The National Aquarium quickly exceeded expectations when it opened on August 8, 1981, drawing more than a million visitors to the Inner Harbor each year, providing a boost to the local tourism industry. In March 1990, the Maryland Department of Economic and Employment Development released a report revealing that the aquarium had received more than 13 million visitors since its opening, bringing in an annual private revenue of $128.3 million and more than $5 million in government tax revenue. In 1996, during NAIB’s fifteenth-anniversary event, Sandra Crockett proudly proclaimed that “15 years after opening, the 20 million visitors to the National Aquarium prove that the aquarium’s decisions cannot be wrong.”[7] The aquarium generates approximately $20.46 million in annual revenue and draws large numbers of visitors to nearby hotels, restaurants, and shopping centers.[8] Maryland Governor Robert Ehrlich Jr. explained the importance of the aquarium to Baltimore’s urban renewal in 2002: “The National Aquarium in Baltimore is one of the most impressive additions to downtown Baltimore’s portfolio of world-class attractions.”[9]

While developing tourism to boost the economy was the priority, the aquarium also conducted conservation and rescue work for marine animals and helped injured animals return to their natural habitats. In 1991, the aquarium established a special aid organization for marine animals, and since then has cooperated with Maryland state government and the Smithsonian Institution to build a network to assist marine animals that ran aground. This network aims to track Chesapeake Bay and Coastal Atlantic marine mammals, help scientific research institutions count marine animals, and assist trapped animals.[10] NAIB has cooperated with Dr. Joseph Geraci, a world-renowned marine mammal pathologist, to improve habitats for and medical conditions of animals within the aquarium and overcome the difficulties of animal conservation and care. Under Dr. Gerald’s part-time scientific direction, the Marine Animal Rescue Program of the NAIB had cared for nearly fifty stranded animals by 1997, ranging from sea turtles to pygmy sperm whales, and returned a substantial number to their natural habitats. Dr. Gerald wanted the aquarium’s visitors to feel more connected to the ocean and give full play to the leadership of the aquarium to better protect the Chesapeake Bay. [11]

In addition, the aquarium has had a positive effect on children’s education, helping them develop an awareness of environmental protection. The aquarium has delivered more than 12,000 classes to people in all fifty states and in other regions, including South and Central America, India, Nigeria, Algeria, Germany, France, and Australia.[12] From March to July 1999, 360 attendees visited NAIB to participate in Leslie M. Adelman and John H. Faulk’s project to explore the impact of the aquarium’s education on visitors’ ideas and behaviors. According to the survey, visitors to the aquarium are generally more concerned about environmental issues than the average citizen after visiting the aquarium, and they have clearly absorbed the basic conservation information.[13] The aquarium’s exhibits deepen visitors’ ideas about animal conservation and broaden their understanding of conservation. In 1994, Nadia Lefkul, an eleven-year-old from Elkridge, Maryland, raised approximately $200 to save the Earth’s rainforests. As a regular visitor to NAIB, she adored the animals and learned about the dangers facing the rainforests through visits and reading books. She bought five acres of rainforest through the Nature Conservancy, an environmental nonprofit, and tried to start an environmentalist club.[14] In 1996, Dr. Valerie Chase, a Biologist at NAIB, launched the “Living in the Water Program,” which focused on aquatic life and how it interacted with the environment, to find innovative ways for teachers to teach science to middle school students in fun and accessible ways.[15]

With the aquarium attracting tens of millions of visitors to Baltimore, however, the debate over keeping marine life in captivity and forcing animals to perform has continued unabated, vexing aquarium officials. Marine science, the environmental movement, and the animal rights movement all grew during this period, and more and more people came to expect more from aquariums. Some scientists contended that NAIB was not concerned about the rights of marine animals since it was built for the economy. James S. Kepley, a marine biologist who was the original executive director in 1978, abruptly resigned two months after the opening, claiming that the position had become one more focused on finances than marine animals.[16]

Since the 1990s, the aquarium’s captive-animal policy has come under intense criticism after a number of dolphin and whale deaths at its mammal pavilion, prompting complaints from animal protection groups and other activists, including journalists.[17] In November 1991, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) launched a campaign against the aquarium’s new marine mammal pavilion, unfurling banners inside the pavilion and complaining about the “killing in captivity” at the aquarium.[18] After a month, a ten-year-old female beluga whale, Anore, died unexpectedly during training at the National Aquarium. Officials stated she may have died as the result of a dolphin attack.[19]

The tragic accident led to ongoing protests from animal activists, who highlighted that the pressures of captivity left marine mammals injured or killed. Moreover, some opponents criticized the Dolphin Theater’s performances as a “Sea Circus.”[20] Dan Rodricks stated that the keeping marine life in captivity in the aquarium was a “Victorian anachronism” that was out of step with a new era of ecological ethics to protect the planet and would only lead to more animal deaths.[21] The ocean is wide, free, and flowing, while the tank inside an aquarium is narrow, confined, and stationary.

After 2000, the National Aquarium embarked on a transformation path, as its managers sought new development to keep pace with the times and made positive changes in the face of doubts and protests from the community. In 2005, the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums called on zoos and aquariums to become models of comprehensive conservation and make a positive transformation in response to the new trend of animal protection movement development: “They face a choice—forge a new identity and purpose or be left behind by the conservation movement.”[22] A growing number of aquariums are sensing a crisis: if they don’t make an immediate transition, they risk being left far behind by the burgeoning conservation movement and losing their status as a conservation hub. The New England Aquarium, Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, and Monterey Bay Aquarium have stated their mission to inspire compassion, curiosity, and conservation for the ocean world, with a focus on ocean conservation and public education. Therefore, the National Aquarium believes that as the leader of aquariums in the United States and the world, it is time to expand marine conservation activities, not only to pursue the profits of animal exhibits.

The National Aquarium’s administrators announced the beginning of a change in their mission on the twenty-fifth anniversary of its opening: “ We continue to take great pride in attracting millions of visitors to the region but also in serving our community as a cultural resource, an aquatic education center, and a steward of the environment.”[23] The aquarium spent the year dedicated to the impact of public education by conducting conservation education programs, including a new series of homeschool programs aimed at students that introduced nearly 21,000 teens to the mysteries of the aquatic world. The aquarium’s faculty and staff also provided professional training for more than 1,000 teachers. Moreover, they developed the “Aquarium on Wheels” work-study program, which has helped dozens of Baltimore youth get on track for careers in science and inspired creativity, responsibility, and self-reliance.[24]

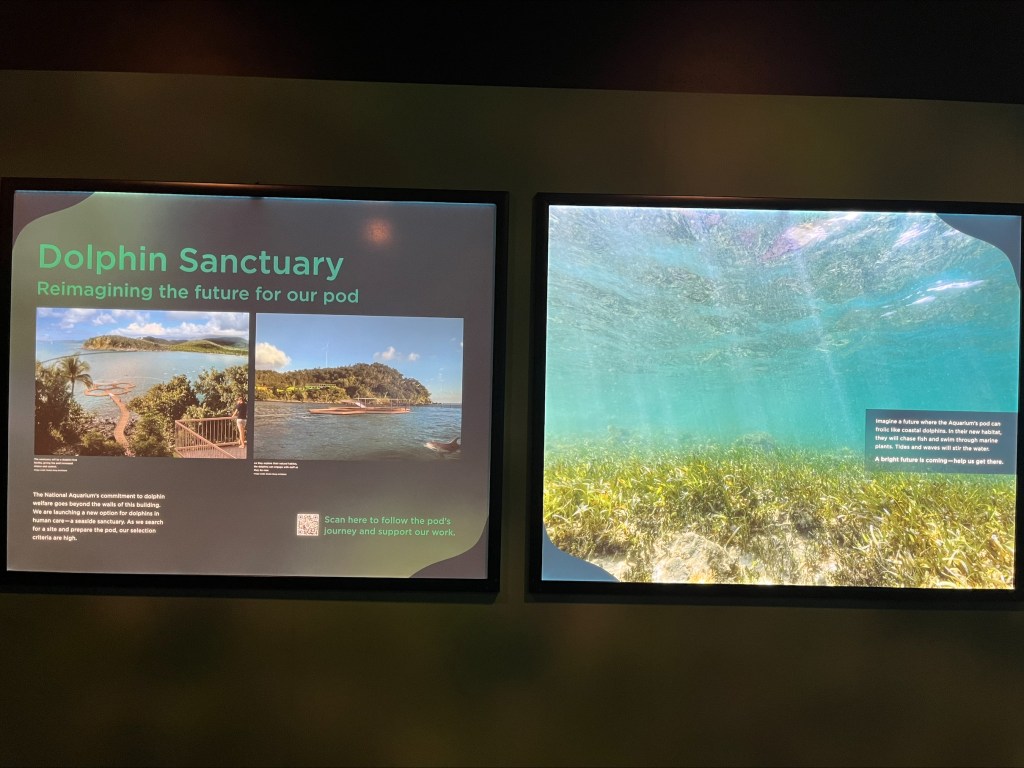

The aquarium suspended its lucrative dolphin show in 2012, instead allowing visitors to observe the interaction between trainers and dolphins at the Dolphin Theater. 2014 was a crucial year for the National Aquarium to rethink its position and make a positive transition. The aquarium announced that they were considering moving dolphins away from captive exhibits and instead placing them in a marine shelter. CEO John Racanelli argued that the National Aquarium must evolve because the officials “know so much more today about the animals and about our evolving audience—and frankly how urgent the need has become to protect the health of oceans and the Chesapeake Bay.”[25]

As the National Aquarium celebrated its thirty-fifth anniversary in 2016, it came to a significant crossroads. When visitors’ interests and opinions continue to shift away from aging attractions, appearance exhibits, and traditional captive methods, the aquarium must respond to the demands of the modern environmental movement and commit to change as the city grows. The aquarium has proposed three points of change: creating a waterfront campus; creating an off-site animal care and rescue center; and the creation of North America’s first coastal dolphin sanctuary, gradually moving captive dolphins to marine sanctuaries.[26] These events marked the transformation of the aquarium, which began to think about its position in the new era and shed the negative title of “ocean circus” to become Noah’s ark for the protection of marine species.

As climate change and ocean crises intensify, the NAIB has become an integral part of the conservation network of the Chesapeake Bay. The aquarium has expanded its Sustainable Seafood Program since 2014, which promotes the sustainable development of seafood harvesting or farming so that production can be maintained without affecting the ecosystems it comes from. To push the plan forward, the aquarium hired marine conservation activist T.J. Tate as its first seafood sustainability director.[27] She believed that “there can be no sustainable seafood without sustainable fisheries.”[28]

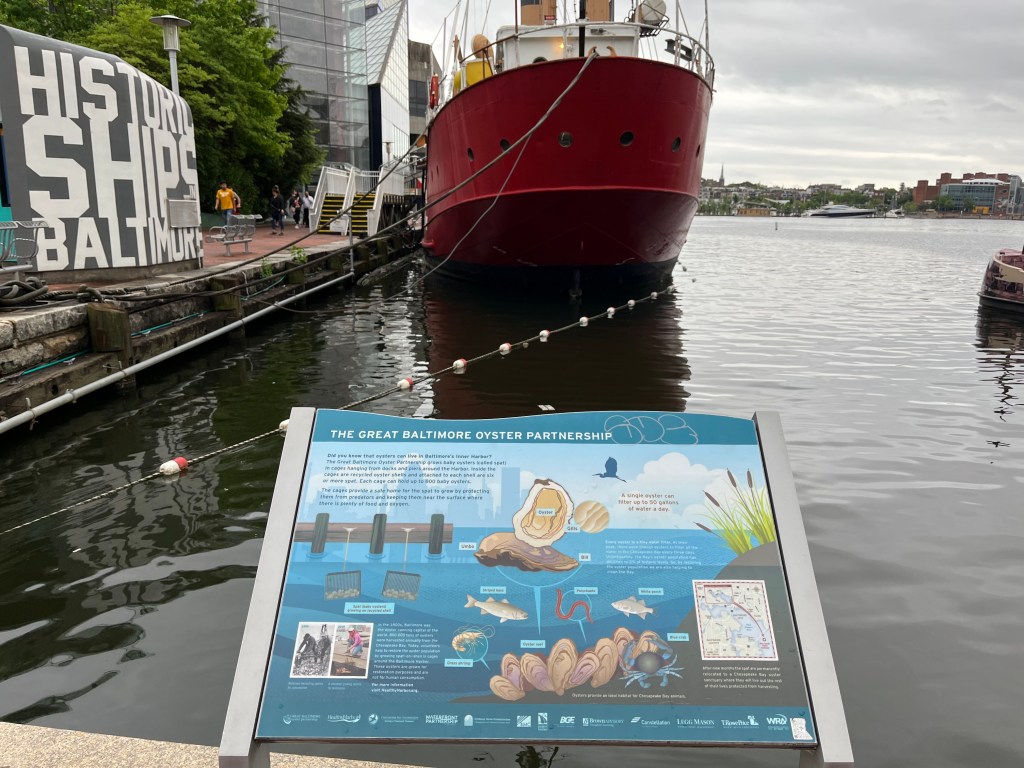

Moreover, the aquarium has extended conservation efforts into the wild, with environmental protection projects in Inner Harbor and Chesapeake Bay. In April 2010, the National Aquarium worked with Waterfront Partnerships, Baltimore Inner Harbor Water Conservation, and other nonprofit organizations to replace long-lost natural wetlands by placing two floating wetlands in the waters next to the World Trade Center, also in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. “It’s a small island in a fairly large body of water,” said Laura Bankey, the aquarium’s manager of conservation, “but that’ll give us an idea, if we scale up this project, what kind of an effect could we have.”[29] The aquarium has been creating new artificial wetlands for more than a decade, helping to improve the water quality of the inner harbor and increase ecological diversity.

Furthermore, the aquarium has deepened cooperation with research institutions to solve ecological problems. Scientists at the NAIB, for example, have joined forces with scholars at Johns Hopkins University and other institutions to contribute to the study of the ecological impact of the oil spill that occurred when the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico blew out and exploded. This reflects the successful transition from museum conservation to habitat conservation. In the summer of 2010, the aquarium, Johns Hopkins University, and Mott Laboratories began monitoring the waters and beaches of Sarasota to study how the BP oil spill affected aquatic life along the Florida coast.[30]

The story of the National Aquarium illustrates how the aquarium, as a miniature marine ecosystem within the city created by humans and nature, blends different ideas and needs to change the environment and change people’s understanding of the city and the ocean. In the twenty-first century, in the face of new trends in marine science, the animal rights movement, and the environmentalism, the National Aquarium seeks to maintain a dynamic balance between the four dimensions of business, entertainment, education, and conservation and to promote the sustainable development of harmonious coexistence between people and the ocean. As climate change intensifies, the National Aquarium believes that the current threat to urban development is mainly the marine crisis, so the focus of work should shift from promoting urban economic development to protecting the marine environment and striving to evolve into a new aquarium that meets the requirements of the twenty-first century. Since its founding, the National Aquarium has served as a bridge between Baltimore and the ocean, both economically and ecologically.

Weilan Ge is a PhD student in history at the University of Florida. Weilan received his bachelor’s degree from Lanzhou University and his master’s degree from Renmin University of China, majoring in world history. He is interested in modern United States history, environmental history, urban history, marine history, and animal history. His master’s thesis explores the relationship between the city and the ocean, based on the transformation of the National Aquarium in Baltimore from the 1980s to present. Now he is focusing on the relationships between cities and oceans and the interactions between humans and animals in coastal cities in the United States.

Featured image (at top): Inner Harbor and the National Aquarium, photo by author.

[1] L.C. Eiseley, The Immense Journey: An Imaginative Naturalist Explores the Mysteries of Man and Nature (New York: Random House, 1957).

[2] “National Aquarium—Conservation” National Aquarium, 2024, https://aqua.org/support/conservation.

[3] The Greater Baltimore Committee, The Greater Baltimore Committee Annual Report (1966), Container 13, Folder 5, Martin L. Millspaugh papers on Urban Planning and Development, MS-0630,. Special Collections, Johns Hopkins Libraries.

[4] Ed Gunts, “Turning 40, the National Aquarium Completes Campaign to Repair Its Glass Roof, Sees Attendance Rebounding after 2020,” Baltimore Fishbowl, Aug. 4, 2021, https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/turning-40-the-national-aquarium-completes-campaign-to-repair-its-glass-roof-sees-attendance-rebounding-after-2020/.

[5] Gilbert Sandler, “The First Aquarium,” Baltimore Sun, Jan. 22, 1991, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-01-22-1991022219-story.html.

[6] Baltimore City — Aquarium Bond Issue https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000734/html/am734–454.html.

[7] Sandra Crockett, “Water World Anniversary: After 15 Years, 20 Million Visitors to Baltimore’s Aquarium Can’t Be Wrong.” Baltimore Sun, 8 Aug. 1996, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-08-08-1996221145-story.html.

[8] Crocket, “Water World Anniversary.”

[9] “Annual Report 2002: Community at the Core,” National Aquarium in Baltimore, 2002, 2.

[10] Liz Bowie, “Bay Hot Line Boosts Marine Mammal Sightings.” Baltimore Sun, 4 Dec. 1991, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-12-04-1991338069-story.html.

[11] Frank Roylance, “Aquarium’s Big Catch Expert” Baltimore Sun, 20 May 1997, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1997-05-20-1997140040-story.html.

[12] Kathleen Hennelly, “Getting Hands-On Experience with Bay Innovation:.” Baltimore Sun, 21 Jun. 1996, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-07-21-1996203121-story.html.

Leslie M. Adelman and John H. Faulk, “Impact of National Aquarium in Baltimore on Visitors’ Conservation Attitudes, Behavior, and Knowledge.” Curator: The Museum Journal, vol 43 (2000): 33-61, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2000.tb01158.x.

[14] Sherry Joe, “Elkridge Girl Tries to Save Rain Forest.” Baltimore Sun, 20 Jun. 1994, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1994-06-20-1994171087-story.html.

[15] Kathleen Hennelly, “Getting Hands-On Experience with Bay Innovation.” Baltimore Sun, 21 Jun. 1996, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1996-07-21-1996203121-story.html.

[16] Michael Burns, “Aquarium Marks 10th Year as Siren to Millions,” Baltimore Sun, 08 Aug. 1991, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-08-08-1991220095-story.html.

[17] Wendy Warren, “Cruelty to Fish.” Baltimore Sun, 23 Jan. 1992, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1992-01-23-1992023150-story.html.

[18] Suzanne Wooton, “Pavilion Protester Makes Waves as Dolphins Do Tricks,” Baltimore Sun, 11 Nov. 1991, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-11-11-1991315033-story.html.

[19] John Rivera, “Dolphin Blamed in Whale Death,” Baltimore Sun, 24 Dec. 1991, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1991-12-24-1991358144-story.html.

[20] Douglas Birch, “Zoos, Aquariums Tired of Attacks over Animal Rights,” Baltimore Sun, 18 May. 1992, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1992-03-18-1992078064-story.html.

[21] Dan Rodricks, “Disturbing Ignorance,” Baltimore Sun, 05 Feb. 1992, https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1992-02-05-1992036143-story.html.

[22] “Building a Future for Wildlife: The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy,” World Association of Zoos and Aquariums, accessed March 1, 2022, https://www.waza.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/wzacs-en.pdf.

[23] “Annual Report 2006: On the Other Side of the Glass,” National Aquarium in Baltimore, 2006, 5.

[24] “Annual Report 2006: On the Other Side of the Glass,” 7.

[25] Yvonne Wenger, “National Aquarium Considers Whether to Keep Dolphins on Exhibit,” Baltimore Sun, May 15, 2014, https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/baltimore-city/bs-md-national-aquarium-dolphins-20140514-story.html.

[26] Kaitlyn Pacheco, “As the National Aquarium Turns 35, Focus Shifts from Captivity to Conservation,” Baltimore Magazine, accessed March 1, 2022, https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/community/as-the-national-aquarium-turns-35-focus-shifts-from-captivity-to-conservation/.

[27] Joe Sugarman, “A Good Catch: How the National Aquarium’s First-Ever Director of Seafood Sustainability Is Shaking Up the Industry,” July 2017, Baltimore Magazine, https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/fooddrink/national-aquarium-director-sustainable-seafood-tj-tate-shaking-up-industry/.

[28] Jenna Blumenfeld, “National Aquarium’s TJ Tate on Sustainable Seafood,” New Hope Network, Aug 24, 2015, https://www.newhope.com/natural-products-expo-east-2015/qa-national-aquarium-s-tj-tate-sustainable-seafood.

[29] “’Floating wetlands’ find a home in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor,” Baltimore Sun, Aug. 08, 2010, https://www.baltimoresun.com/maryland/bs-xpm-2010-08-08-bs-md-floating-wetlands-20100808-story.html.

[30] Andrea Walker, “Hopkins to Study Oil Spill Impact on Florida Ecosystem,” Baltimore Sun, July 19, 2010, https://www.baltimoresun.com/bs-mtblog-2010-07-hopkins_to_study_oil_spill_imp-story.html.