This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Matthew Adair

For many Americans, summer is a season of travel. The ritual of leaving home for somewhere more relaxing (or invigorating) has a long history. Since at least antiquity, “escaping the city” has been a common tradition among the well-to-do, from Roman villas to nineteenth-century American country estates.[1] Think of President Truman’s Little White House in Key West, or Campobello, a town between Maine and New Brunswick where President Franklin Roosevelt spent many summers. Perhaps the most renowned example is the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. A 135,280 square-foot summer house built by the Vanderbilt family in 1895, Biltmore epitomizes the opulence of America’s Gilded Age, in which conspicuous leisure and summer vacationing rose to prominence.

Influenced by the legacy of the Gilded Age, the domestic expressions of wealthy Americans in subsequent decades were not limited to the coastal elite and blue-blooded families of political pedigree. In cities across the country, upper-class denizens carved out their vision of seasonal summer bliss in suburban, exurban, and rural locales near and far. But more than mere periods of leisure, summer presented an opportunity to strengthen critical social and professional connections that maintained elite dominance in political, social, and economic spheres in early twentieth-century American cities. During a time when summer vacations (and paid time off) were a rarity, the urban elite used seasonal residences as a mode of peacocking their social position as well as displaying class solidarity with their social peers.[2]

Decades later, we have a thorough understanding of exactly where many wealthy families in the Roaring Twenties chose to spend their halcyon summer days, thanks to the publication of upper-class social directories. Both in their urban environs and out of town, wealthy households restricted themselves to particular spaces deemed worthy of their shared class experience of leisure. Put more succinctly by urban geographer Stephen Higley, “geographic propinquity is an essential pillar upper-class solidarity.”[3]

Before Facebook or LinkedIn, Printed Directories Helped Establish Social Networks

If the idea of these directories seems hard to believe, think them as private address books for select households. For many decades, there were two principal directories of the upper classes: the Blue Book and the Social Register. According to work by historian James Borchert, the directories helped elite families “sort out who ‘belonged’ in Society and who did not.”[4] In Cleveland, the fifth largest US city in 1920, the Blue Book was considered less exclusive, containing 2,940 prominent families against just 1,134 listed in the Social Register.[5] Borchert writes that the acceptance to the Register “involved a formal application process with a committee,” while the Blue Book processes “remain more obscure.”[6]

Although inclusion criteria was not explicitly stated, other scholars have also gathered that the Blue Book was more likely to “include a wider range of racial, ethnic, religious, and social groupings” than the Social Register—which is still in publication today.[7] Nevertheless, households that were not white, Anglo-Saxon, and protestant (WASP) were less likely to have been included in either publication. Arguing the process is best described as “idiosyncratic,”[8] Stephen Higley’s lens considers the directories’ role maintaining the “associational arrangements that have made it possible for members to pass through life with very little significant contact with other social classes.”[9] These arrangements, he argues, “affirm cultural and group solidarity with the upper class and clearly delineate class boundaries” from the rest of society (with a decidedly lower-case “s”).[10]

Higley’s book, Privilege, Power, and Place: The Geography of the American Upper Class (1995) analyzed the 1988 edition of the Social Register and explored “the intersection of class, status, and geography at the upper end of the American socioeconomic spectrum” by looking at the “places created and maintained by the upper class.”[11] To investigate this geography, he categorized 32,398 households and found that only 21.6 percent of households listed a summer residence. With less than a quarter of wealthy households in the pattern of annual summering, those that did were likely on the higher end of a closed social network that leveraged seasonal vacations to promote “inter-metropolitan social, business, and matrimonial alliances.”[12]

Class Solidarity, Both In-Town and Out-of-Town

A rather nebulous concept, one component of class solidarity brought to life by the Blue Book are the insular social networks of the urban elite. Along with similar legacy documents like the HOLC residential security maps, the directories reveal how polite society was spatially linked through certain neighborhoods and socially connected using directories as a validating tool. Analyzing “upper-class collective behavior,” Borchert and Borchert find that elites in each US city constructed residential ideologies that displayed “a unity in its choice of a residential environment.”[13]

Yet exclusive socializing extended outside of urban confines into the summering habits of wealthy Americans. Without a doubt, elites forged connections both in their income-and race-segregated urban communities as well as in their similarly stratified resorts. These seasonal opportunities helped form social, political, and economic connections central to urban futures. While much scholarship on twentieth-century urban life focuses on the stratified conditions of urban neighborhoods, there are important contours of social relations that emerge when looking at the summering patterns of the urban elite. In fact, understanding cities as just one place where elites spent their privileged days puts into perspective the policy outcomes they would have been motivated to support—or oppose—considering that many households spent months away from their permanent residences every year.

Conspicuous Leisure: From the Society Pages to Social Media

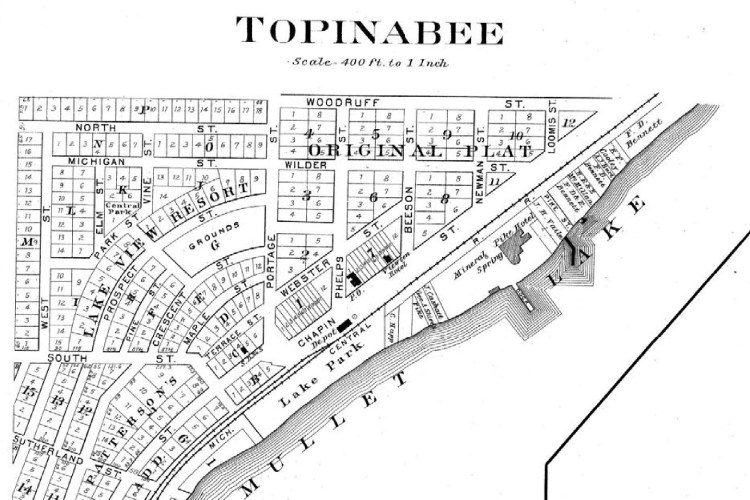

In addition to directory listings noting whether a household maintained a summer residence, the society pages of local newspapers also ran announcements about the travel plans of residents. “Mr. and Mrs. James Edward Elliott and their granddaughter, Jane Elliott Stribling, 1040 Franklin Avenue, left Thursday for their summer home at Topinabee, Michigan,” read the society page of The Columbus Dispatch on July 10, 1910. The Elliott household wanted their social network to know they’d be out of town over the summer—not just vacationing but staying at “their summer home” in picturesque northern Michigan, about 400 miles north of Columbus. The Elliott family made this same announcement almost every year, through at least 1926.

These resort towns were just one component of a comprehensive apparatus of WASP culture that metastasized in the early twentieth century. Sociologist and observer of WASP culture Edward Digby Baltzell Jr. wrote that the privileged elite of this era “gained a profound self-consciousness through a network of exclusive clubs, boarding schools, resorts, and Ivy League colleges that promulgated a subculture of common values.”[14] The leisure projected by vacationing was an important means of realizing class solidarity during this period.

Peripheral Cleveland vs. Distant Columbus

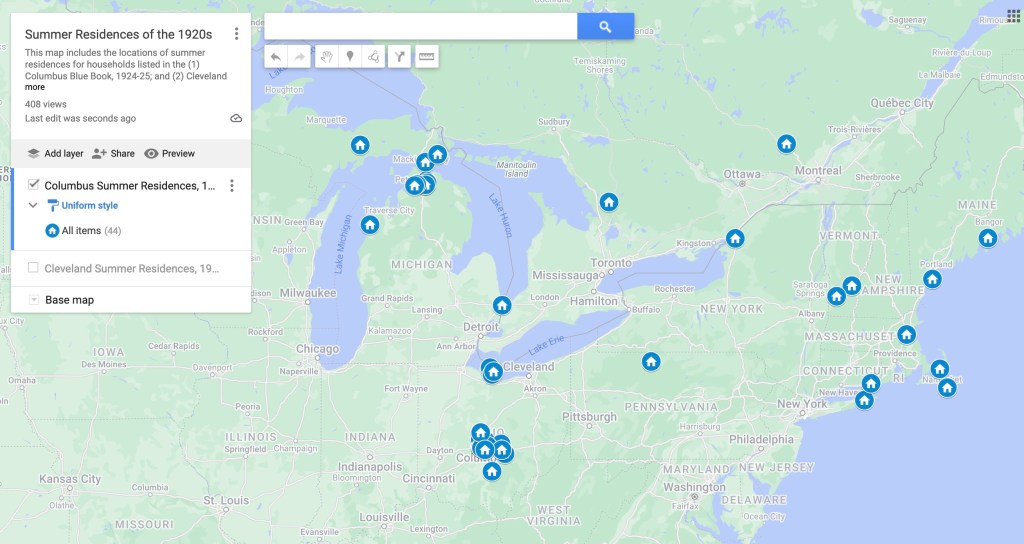

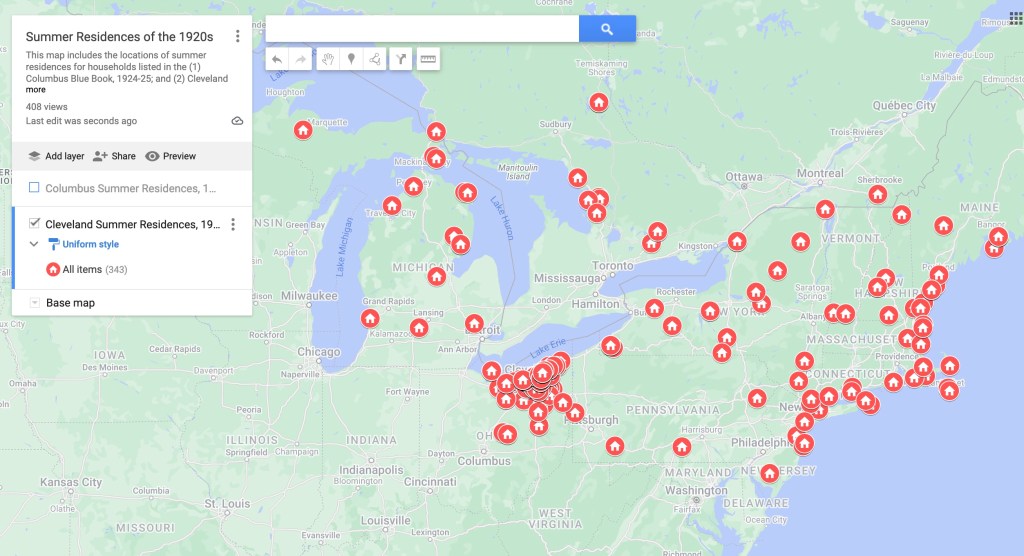

As two illustrative examples of upper class summering behavior, I have recorded the 340 summer residence locations of the Blue Book households for Cleveland and the 44 summer residences in the Columbus edition. With a population of 796,841 in 1920, Cleveland ranked as the fifth most populous city in the nation. At the same time, Columbus had just 237,031 people. As such, the number of summer residences—as well as the total number of households listed in the directory—was much smaller for Columbus.

Despite more than 100 households spending their summers outside of Ohio, Clevelanders had a penchant for local country estates, more so than Columbus residents. Of the 340 summer residences listed in the Cleveland edition, 57 percent were located in suburban Northeast Ohio and 70 percent were located within Ohio. By contrast, just 25 percent of listings in Columbus were located in suburban Central Ohio, with only 39 percent of the 44 summer residences being in-state. Columbus households, on the whole, felt more compelled to spend their summers outside of Ohio.

Table 1: Summer residences by state/region for Columbus and Cleveland

| Columbus | Cleveland | |||

| Quantity | Percent | Quantity | Percent | |

| In-state | 17 | 39% | 238 | 70% |

| Michigan | 13 | 30% | 16 | 5% |

| Mid-Atlantic | 3 | 7% | 35 | 10% |

| New England | 8 | 18% | 38 | 11% |

| Ontario | 1 | 2% | 11 | 3% |

| Quebec | 1 | 2% | 1 | 0% |

| West | 1 | 2% | ||

| Overseas | 0 | 1 | 0% | |

Columbus residents also seemed to have enjoyed Michigan at a higher rate than Clevelanders. About 30 percent of summer residences for Columbus Blue Book members were located in northern Michigan, as opposed by just 4.7 percent for Clevelanders. In fact, this disparity is the most striking difference between the summer residential patterns of the elite in these two cities. Columbus appears to have had a strong connection to northern Michigan, with one outpost of prominent families being named “Columbus Beach,” on the shores of Burt Lake in Indian River.

Table 2: Summer residences by locale typology for Columbus and Cleveland

| Locale | Columbus | Cleveland |

| Lakeside/Island | 39% | 13% |

| Oceanside | 14% | 10% |

| Rural | 23% | 21% |

| Suburban | 25% | 57% |

One factor that might have influenced the vacationing patterns of these two cities is attraction to water. Categorizing the summer residences by location type adjacent to water (Table 2), we can see that Columbus residents were vacationing lakeside and oceanside at a higher rate. Considering that Cleveland residents lived throughout the year on the shores of Lake Erie, this finding seems logical. Not located on the shore of a Great Lake, Columbus residents more frequently sought recreation and relaxation outside of Ohio. Another key factor influencing the location of seasonal residences, like most real estate development, was transportation access. Located along the Michigan Central Railway—which had connections from Toledo through Detroit and north to the tip of Michigan’s “mitt”—Topinabee and other resort areas were accessible from both Cleveland and Columbus by train.

More than Just a Directory

Elite directories contain much more than just names. They show how the elite have long shaped consumer tastes. Through directories and society pages, historians can draw connections among American industry, architecture, and landscape architecture. In one of North America’s most urbanizing periods and before mass suburbanization, elite households left cities in significant numbers to enjoy leisure, privacy, and—yes—class solidarity through their seasonal pilgrimage.

What push factors might have led these families to build homes in quieter locales? Outside of social pressure, cities in the 1920s were becoming “modern” in a way that might have shocked the polite sensibility. For example, “approximately six million immigrants arrived in each decade between 1880 and 1920.”[15] In addition to this cumulative effect of cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity, the machine age was arriving. In the 1920s, cars began to clog city streets and “motor vehicle accidents in the US killed more than 200,000 people.”[16] Over the following decades, in the words of prolific urban observer Lewis Mumford, city cores succumbed to “intense congestion that has in fact been emptying out the big city, hurling masses of people into the vast, curdled Milky Ways of suburbia.”[17]

As more elite directories are digitized through the diligent efforts of libraries and archives, scholars will have increasing opportunities to draw connections—social and spatial. Combined with the society pages, historians have an opportunity to sketch out how networks of relations in the early twentieth century were linked to economic and political power. In analyzing the behaviors, customs, dwellings, and investments of the elite during this critical period of American urbanization, evidence reveals the incredibly strong class solidarity formed and maintained by elite institutions and customs.

Matthew Adair is a PhD candidate in Urban Planning, Policy, and Design at McGill University in Montreal. As a certified planner with a decade of professional experience, he brings a unique applied perspective to his research. While Matthew’s dissertation examines the role of financing in the production of market-rate multifamily housing, his interdisciplinary interests include post-industrial Rust Belt places, planning history, and neighborhood change.

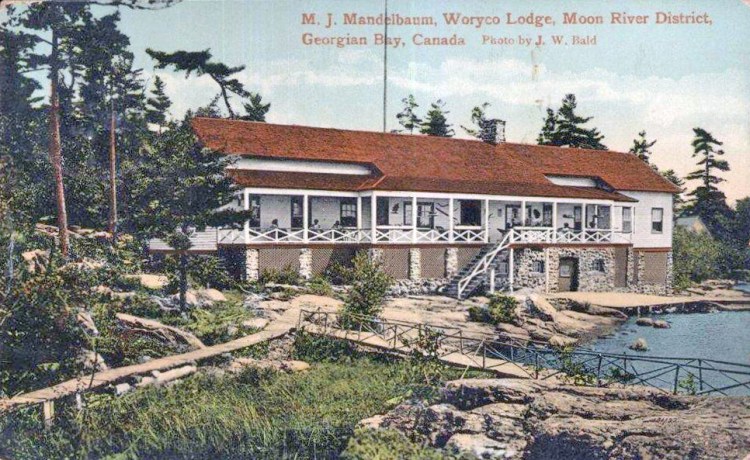

Featured image (at top): Summer residence of businessman M. J. Mandelbaum, located on Somerset Island in Ontario, Canada. A private, 20-acre island in the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. For decades, Clevelanders made the journey northward to enjoy invigorating activities and relaxation at the spacious 17-room “Woryco Lodge.” From Postal History Society of Canada and G. Doug Murray. “A Communication Lifeline – S.S. MIDLAND CITY,” The Gerogian Courier, no. 51 (August 2013).

[1] Richard Lyman Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities, Reprint edition (New York: Vintage, 1993); Pierre de la Ruffinière Du Prey, The Villas of Pliny from Antiquity to Posterity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

[2] In 1910, President William H. Taft declared Americans would benefit from two or three months of vacation annually. Source: “President William Howard Taft Wanted All Of The U.S. To Have 3 Months Of Vacation,” All Things Considered, Washington, DC, National Public Radio (NPR), August 1, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/08/01/747368652/president-william-howard-taft-wanted-all-of-the-u-s-to-have-3-months-of-vacation.

[3] Stephen Richard Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place: The Geography of the American Upper Class (Rowman & Littlefield, 1995), 63.

[4] James Borchert, “From City to Suburb: The Strange Case of Cleveland’s Disappearing Elite and Their Changing Residential Landscapes: 1885-1935,” in Proceedings of the Ohio Academy of History (Marion, OH, 1999), 13-14.

[5] Borchert, 13-14.

[6] Borchert, 13-14.

[7] James Bochert, and Susan Borchert, “Downtown, Uptown, Out of Town: Diverging Patterns of Upper-Class Residential Landscapes in Buffalo, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland, 1885–1935,” Social Science History 26, no. 2 (2002): 311–46, https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1017/S0145553200012372, 318.

[8] Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place, 29.

[9] Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place, 18.

[10] Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place, 30.

[11] Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place, 129.

[12] Higley, Privilege, Power, and Place, 129.

[13] Borchert and Borchert, “Downtown, Uptown, Out of Town,” 313.

[14] E. Digby Baltzell, Judgment and Sensibility: Religion and Stratification (New York: Routledge, 2017), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351294683, 11.

[15] Richard Foglesong, Planning the Capitalist City: The Colonial Era to the 1920s (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 83.

[16] Peter D. Norton, Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 21.

[17] Lewis Mumford, The Urban Prospect: Essays (London: Secker & Warburg, 1968), 202-03.

Slideshow image sources:

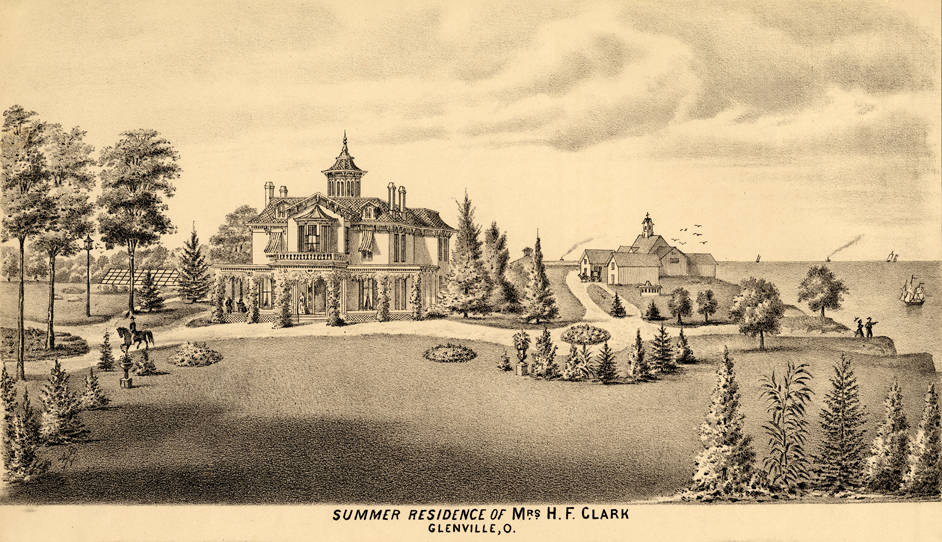

Summer Residence of Mrs. H. F. Clark, Titus, Simmons and Titusm 1874, Greater Cleveland Print Collection, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections, Cleveland State University, https://clevelandmemory.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/print/id/106/

Summer residence of John D. Rockefeller, E. Fenberg, Cleveland, Ohio, 1917, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/postcard/id/10462/rec/1

Summer residence of John Newell, M. Smith, Mentor, No date, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/postcard/id/19534/rec/1

Summer residence of the Woodhull family, MLS (Multiple Listing Service) Real Estate Cards Collection, Columbus Metropolitan Library, https://digital-collections.columbuslibrary.org/digital/collection/p16802coll36/id/130351/rec/1

Summer residence of Gertrude Divine Webster, image Courtesy of Manchester Historical Society.

Canoeing on Mullett Lake, Inland Water Route Historical Society, Alanson, Michigan https://www.michiganwatertrails.org/location.asp?ait=av&aid=1643

A plan of Topinabee, Inland Water Route Historical Society, Alanson, Michigan https://www.michiganwatertrails.org/location.asp?ait=av&aid=1643