This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Jackie Wu

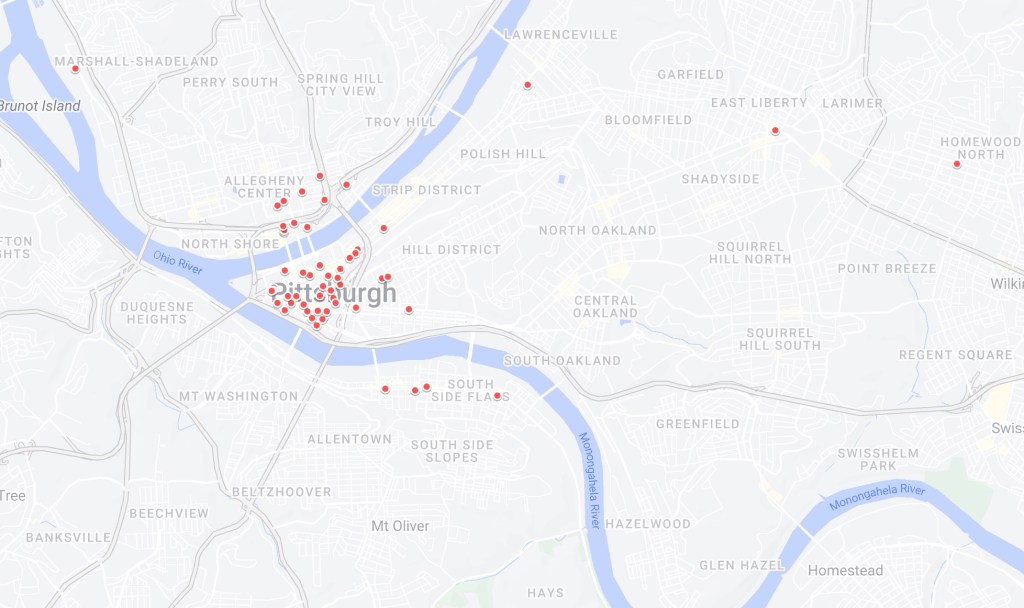

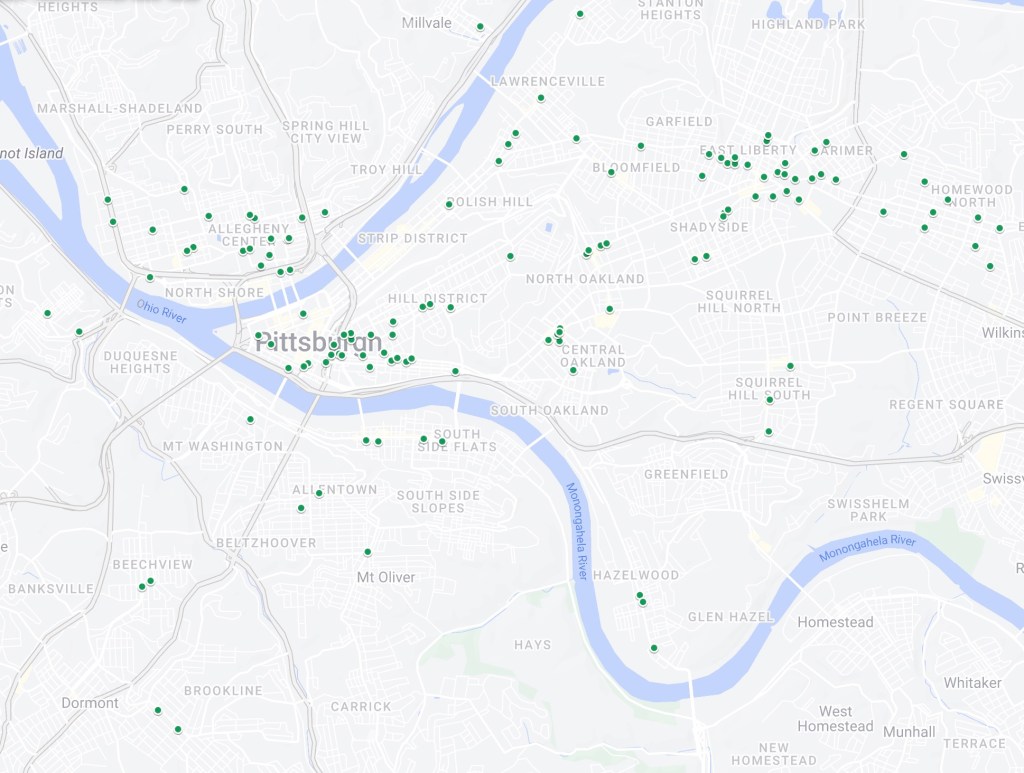

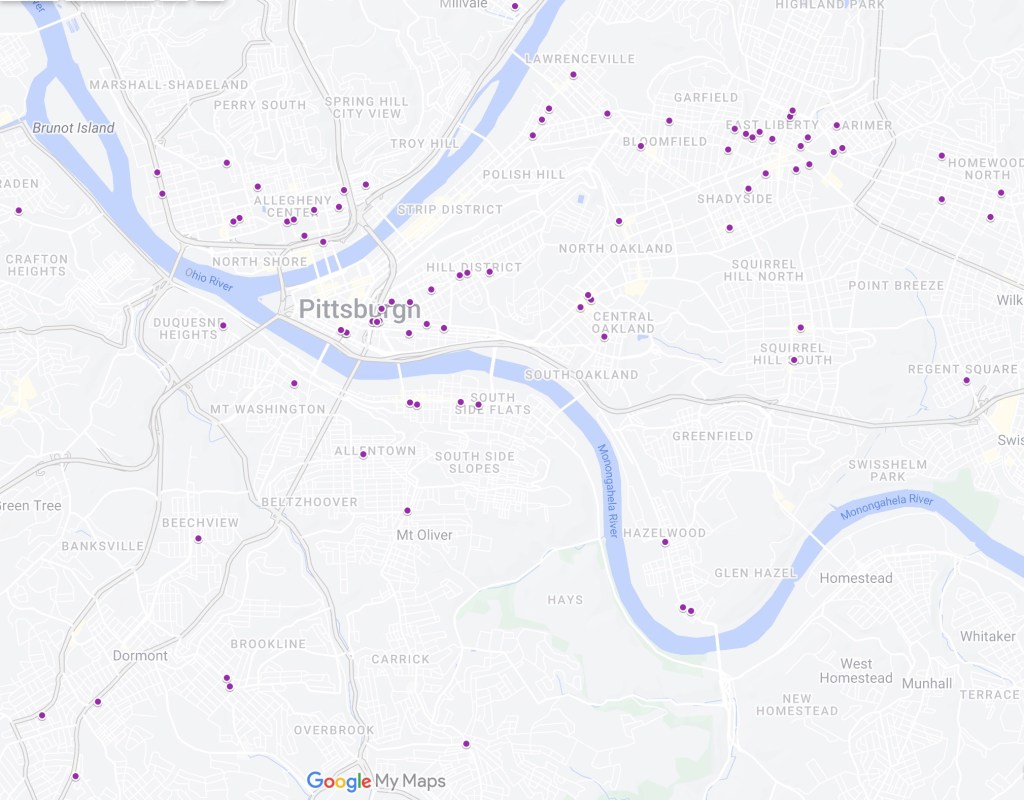

Chinese-owned laundries dotted the urban landscape of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from the late nineteenth century well into the post-World War II years. Tucked in between houses, restaurants, and other businesses, the number of Chinese laundries peaked in the 1930s with 129 establishments across the city, concentrated in residential areas and along major throughways.[1] Only a few were ever located in the historical neighborhood known as Chinatown.

I encountered several lists of these laundries while skimming the pages of old city directories last summer. Invited to share some of the history of Pittsburgh’s Chinese community at the Heinz History Center in October 2023, I wondered how I might translate these neat lists of names and addresses into an engaging presentation that could expand and challenge the audience’s preconceptions about the lives of Chinese immigrants in the city. How did these immigrants build connections with neighbors and customers across boundaries of race and class? How might their widespread historical presence help residents today navigate their own sense of belonging?

While attending Carnegie Mellon University from 2018 to 2022, I was lucky that my growing fascination with the history of Chinese immigration to Pittsburgh coincided with a resurgence of public interest in the historical Chinatown. Local artists, scholars, and former residents and their families, alongside organizations like OCA Pittsburgh, led this effort, through preservation work and tireless advocacy. Once nestled in the lower part of the downtown central business district, the small but tight-knit Chinatown was home to grocery stores, restaurants, and other gathering spaces for the region’s Chinese residents in the early twentieth century. Construction of the Boulevard of the Allies in the 1920s cut through the area, and subsequent urban redevelopment further displaced its residents. Left with only one remaining establishment, the neighborhood finally unveiled its long-overdue historical marker in April 2022 in front of the Chinatown Inn restaurant.

The geographical spread of Chinese laundries, however, shows that even as Chinatown was the beating heart of the Chinese community, the lives of these immigrants in Pittsburgh expanded far beyond the bounds of the ethnic enclave. Chinese laundries preceded the development of Chinatown, with Hong Lee’s “Chinese Laundry from California” first listed in the 1875-76 Business Directory of Pittsburgh at Sixth Avenue and Smithfield Street, downtown. Over the next decade, the number had grown to at least fifty-nine Chinese laundries.[2]

These were primarily hand laundries run by a few individuals at most, in contrast to much larger white-owned steam (also called “power”) laundries that regularly employed dozens of workers. Without heavy machinery, hand laundries had a low barrier to entry and high earning potential, with the tradeoff of working hours that could span from 8:00am to 1:00 or 2:00am.[3] Furthermore, though Chinese immigrants did not labor directly in Pittsburgh’s booming steel mills, their success in laundry work nonetheless went hand in hand with the nearby, expanding industrial infrastructure. An investigator of the 1910 Pittsburgh Survey, Elizabeth B. Butler, noted that general demand for laundry businesses rose significantly due to smoke from the city’s factories, writing that “railroad lines, the travelers, the hotels, have helped make the industry prosperous in Pittsburgh, but the best allies of the laundrymen have been the black smoke and the smoke-filled fog.”[4]

Centering her 1996 doctoral dissertation around Chinese laundries and their clientele in Pittsburgh, historian Joan Shiow-Huey Wang traced the impact of labor competition and technological innovations on laundries’ employment practices and spatial distribution through the twentieth century. Early in the century, expectations of starched and ironed formal day wear, with clean white shirts and stiff collars, kept middle-class office workers reliant on hand laundries that skillfully starched, dampened, and ironed their clothing. Over the next few decades, as workers moved to growing residential areas in the east section of the city, larger power laundries incorporated delivery services, while hand laundries simply relocated to the new neighborhoods. Though Chinese and white-owned laundries across the city continued to compete for patrons, they increasingly occupied different niches by the 1920s.

After World War I, white-owned power laundries attracted the business of middle-class families, while Chinese laundries increasingly served less-affluent customers who lived in apartments and rooming houses. The distribution of Chinese laundries in the 1930s shows the majority located in sections rated “Declining” or “Hazardous” on the 1937 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map, ratings usually attributed to the presence of “undesirable” Black and immigrant populations, lower incomes, and older housing stock. Pittsburgh’s famed Hill District, a grouping of historically Black neighborhoods, was home to at least a dozen Chinese laundries during this time.[5]

I ultimately decided to open my presentation last October with simple maps like these, encouraging the audience to imagine the centrality of these immigrant entrepreneurs in the development of not only Chinatown itself, but also a range of neighborhoods across the city. Many attendees were shocked to see laundries that once existed around the corner from their present-day homes or were surprised by the sheer number of Chinese residents that lived outside Chinatown. Especially touching were some descendants of former laundry owners who remarked that they recognized some of the locations where their relatives had worked.

After the event, a member of the audience asked about what the relationship was like between Chinese residents and other ethnic groups. Seeing the distribution of Chinese laundries is one way to highlight the connections these workers must have formed living in these spaces and interacting with regular customers of different ethnicities. Moreover, some laundries may have hired non-Chinese workers from their surrounding communities—in cities like Chicago and New York, Chinese laundries were known to employ Black women in times of high demand.[6] Often in one place for many years or even multiple generations, their sustained presence indicates relative economic success, as their services were profitable enough to remain in operation.

Maps help to highlight the ties that existed between Pittsburgh’s Chinese residents and the communities where they lived and labored. Chinese laundry workers were clearly connected socially and economically to the diverse neighborhoods where they spent most of their time. Prominent anti-imperialist leader Liu Liangmo regularly called for racial equality and interethnic solidarity in his column for the Pittsburgh Courier, the largest Black newspaper in the United States, pointing out that across the country, many Chinese restaurants and laundries depended “a great deal on the goodwill and mutual help” of their Black neighbors.[7] These workers further relied on each other through larger kinship networks, membership in benevolent associations, and weekend trips from their scattered locations to shop, bond, and relax with friends in Chinatown.

I was honored to speak about these histories alongside artists, scholars, and community members who discussed their own connections to the city’s history of Chinese immigration. Marian Lien, OCA Pittsburgh president, recounted the twelve years of advocacy and four separate application attempts to finally get historical landmark status for Chinatown. Artist Lena Chen, co-founder of the JADED collective, presented her award-winning short film “The Last Mayor of Chinatown,” which highlights the story of the late Yuen Yee and his daughter Shirley. Shirley, in turn, shared stories from her father’s incredible collection, which she has carefully stewarded for years and recently donated to the Heinz History Center. Rounding out the event, Lydia L. Ott reflected on her childhood in Chinatown alongside her granddaughter Lydie.

As time progresses, telling these narratives helps a new generation of residents discover a sense of identity and belonging. Lena has written about her journey learning and finding inspiration in the long-overlooked Asian American histories of the city when she arrived in Pittsburgh to attend graduate school. Children and grandchildren of former Chinatown residents are coming forward with family stories, and the turnout for last October’s event is ample evidence that the public is interested.

These histories also disrupt common assumptions about the trajectories of historical immigration. Reflecting demographic changes of the last few decades, more and more Asian businesses are opening across Pittsburgh, especially in the Oakland and Squirrel Hill neighborhoods. Residents are excited to see more Asian restaurants and stores open. Unknown to most, however, many of these areas had once featured thriving Chinese-owned laundries.

I worked in a small Taiwanese bakery in Squirrel Hill my senior year of college. Sitting behind the register, my view was of the popular bubble tea chain Kung Fu Tea across the street, which had opened in 2020. Going over the city directory recently, I realized that a Chinese laundry had once stood in that exact spot—Yee Wah at 2107 Murray Avenue. There were once a dozen Chinese laundries within a few blocks of French-Asian bakery Tous Les Jours, which opened this past March to a line wrapping around the corner. I wondered how many customers might be surprised to learn that some Chinese had almost certainly been spoken on that street a century earlier.[8]

Pittsburgh is nicknamed not only the Steel City, but also the City of Bridges, a moniker that reflects the 446 spans built over its valleys, creeks, and rivers.[9] The legacy of Chinese laundries is one that bridges the histories of ethnic groups and hints at the connections they formed with one another, showing that we might discover more by considering the historical Chinese community not as exceptional or insular, but rather an integral part of Pittsburgh’s industrial past. The story of Chinese laundries is also an intergenerational bridge, connecting residents today with their predecessors and showing that Asian Americans built lives in the city long before the present day.

Jackie Wu is a PhD student in History at Yale University. Her current projects focus on race, migration, disease, and public memory. She holds a BA in History and a BS in Business Administration from Carnegie Mellon University, where her senior thesis explored late nineteenth-century Chinese labor in the northeastern United States.

Featured image (at top): First Class Chinese Laundry is visible at 512 Court Place, “Ladies Dining Room” (1939), Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, 1901-2000, University of Pittsburgh.

[1] City Directories, 1880-1960. Ancestry.com, U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database online] (Lehi, UT: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011).

[2] Joan Shiow-Huey Wang, “’No Tickee, No Shirtee’: Chinese Laundries in the Social Context of the Eastern United States, 1882-1943,” PhD diss., Carnegie Mellon University, 1996.

[3] Wang, 68.

[4] Elizabeth Beardsley Butler, Women and the Trades: Pittsburgh. 1907-1908 (Russell Sage Foundation, 1910; reprint University of Pittsburgh Press, 1984), 161.

[5] Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, et al, “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America,” eds. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, American Panorama: An Atlas of United States History, 2023, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining.

[6] Wang, 283.

[7] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: Chinese Editor Deplores Discrimination—Calls for Unity of Negroes, Chinese,” The Pittsburgh Courier, Feb. 17, 1945.

[8] Polk’s City Directory, 1931, Ancestry.com, U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995.

[9] Brady Smith, “Pittsburgh: The City of Bridges,” Heinz History Center, https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/western-pennsylvania-history-pittsburgh-the-city-of-bridges/.