This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Matthew McKeown

Third places are spaces people go to get away from work and home life. These spaces are vital for connecting community members and essential for urban renewal. Recently, there have been arguments about the decline of third places.[1] The reasoning is multicausal, including the pandemic, the rising cost of living, the distance created by social media and the internet, poorly built suburban areas, and downtowns suffering from what some term the “Doom Loop,” a phenomenon which has accelerated in the twenty-first century, but one which has existed since the 1950s. The decline of third places can lead to the deterioration of community.[2]

Without spaces that connect us to our informal public life, people may feel fractured and disconnected, losing a shared sense of democracy, diversity, and belonging. Third places, such as gyms, parks, and community centers, operate as connectors within neighborhoods and between different locations. When areas are well-connected by transportation lines and feature walkable streetscapes, third places thrive. Financial security is necessary for both visitors and owners to ensure these spaces remain open. Additionally, government support is required to sustain these spaces, though it should cease from inducing ideologies within them.[3] Third places provide a space where specific organizations can consolidate, and where people can relax and mingle, creating a sense of community and inclusion. Having spaces for events, organizations, and gathering places for residents to form new opinions, debate, and informally gather helps generate community, fosters public interaction among different groups, improves social capital, and creates informal spaces of civic society.

The history of community development and urban revitalization of twentieth-century Winnipeg through sports and social organizations illustrates this perfectly. A railway city unique for its diversity, Winnipeg grew substantially around the turn of the twentieth century. Amid these conditions, urban revitalization became a crucial project for sports reformers in Winnipeg. To alleviate social tensions produced by rapid growth, several community organizations founded boxing clubs.

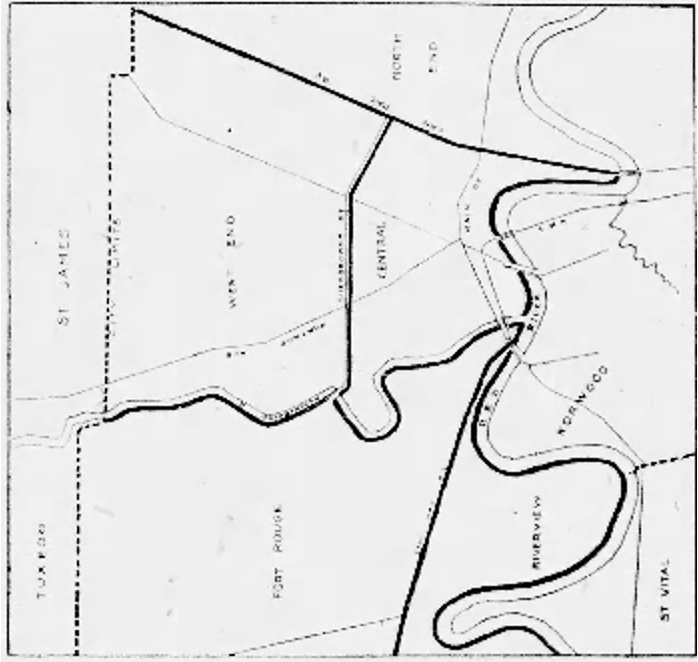

Winnipeg historians argue that where people lived and their occupations divided the city along ethnic, class, and religious lines.[4] Inhabitants created these boundaries and used key landmarks, both built and natural, to give material reality to these divisions. As a railroad juncture, the railroad tracks played into civic boosterism, as residents imagined the city as the Chicago of the North. The tracks also acted as a geographic boundary that divided the city by north/south poles. North of the tracks, known as the North End, was an immigrant-dense, low-income area. In contrast, south of the tracks was the financial center and residence of the middle class and the first-and second-generation British Isles population. This area is divided into several districts: the Central or Downtown, Fort Rouge, and the West End. The Red River, which carved through the heart of Winnipeg, was also an imagined and natural boundary. West of the river represented Protestant and British heritage, whereas east of the river, St. Boniface, was French and Catholic.

By the twentieth century, the YMCA had two locations: Vaughn Street in the South and Selkirk in the North. Vaughn Street members typically were first-and second-generation immigrants from the British Isles. The Selkirk location was opened to rejuvenate the North End. It was not to keep British Isles immigrants from coming to the Vaughn Street location, but to create a melting pot for both classes and ethnicities. YMCA board members recognized the potential for urban revitalization in addressing problems such as crime, poverty, immorality, and child delinquency. Staff believed that social welfare was the key to combating urban decay in the North End, and they implemented a four-fold curriculum: physical, educational, spiritual, and social. Boxing became an integral part of this curriculum, intended to assist not only white, first-generation immigrants, but also the second-generation immigrants who traced their lineage to the British Isles and newly arriving immigrants from Jewish, German, Chinese, and Scandinavian backgrounds, who were adjusting to the new society.

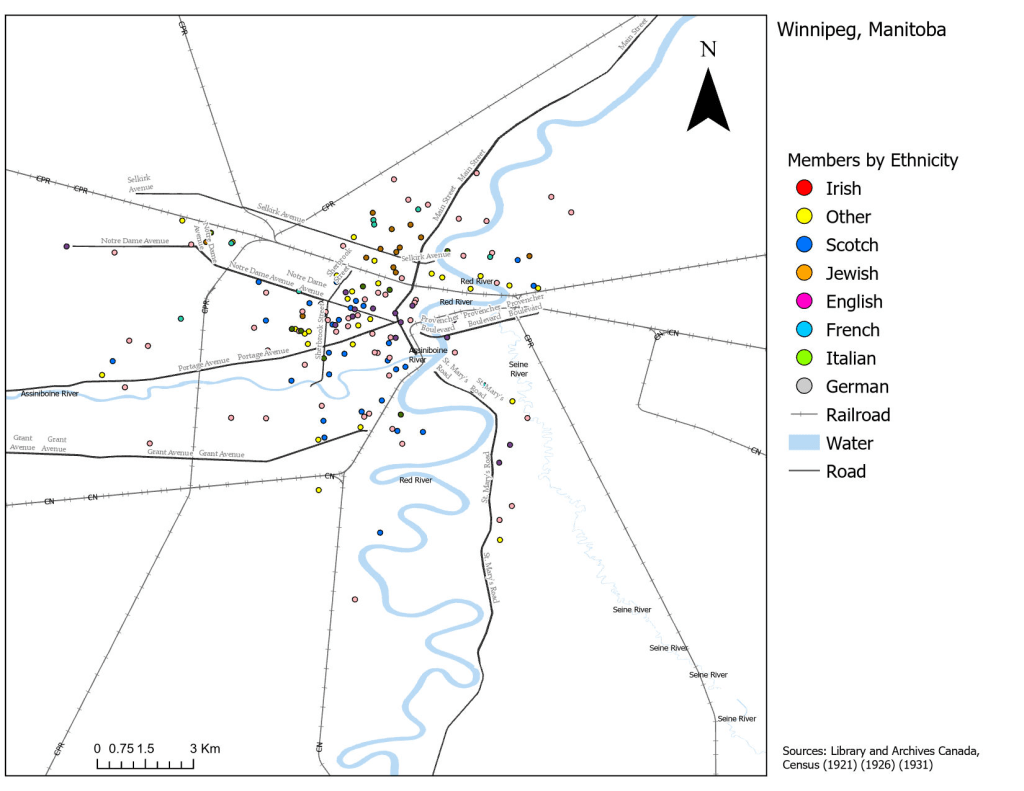

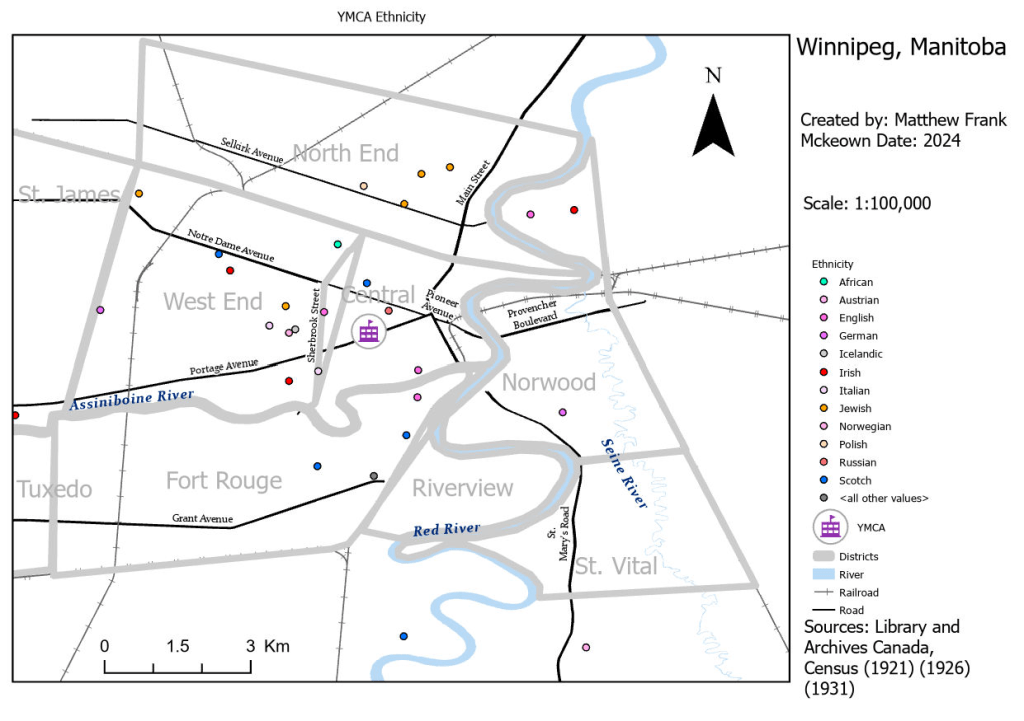

Upon finding sources at the Manitoba Archives that showed the YMCA claiming to be attempting to diversify its membership, I asked if the YMCA did break these barriers by offering sports to a diverse group of men and young boys. With the information about YMCA members, such as membership rolls, I also began to look at parallels with other gyms in the city. Methodologically, geographical information systems (GIS) provided me with a means to showcase my qualitative and quantifiable data by offering a method to visually display the quantitative data that sometimes gets lost in the text. It helped me see new spatial connections that emphasize that to understand segregation in the city, historians must continue to look at where people work and live, but also consider where they go in between.[5]

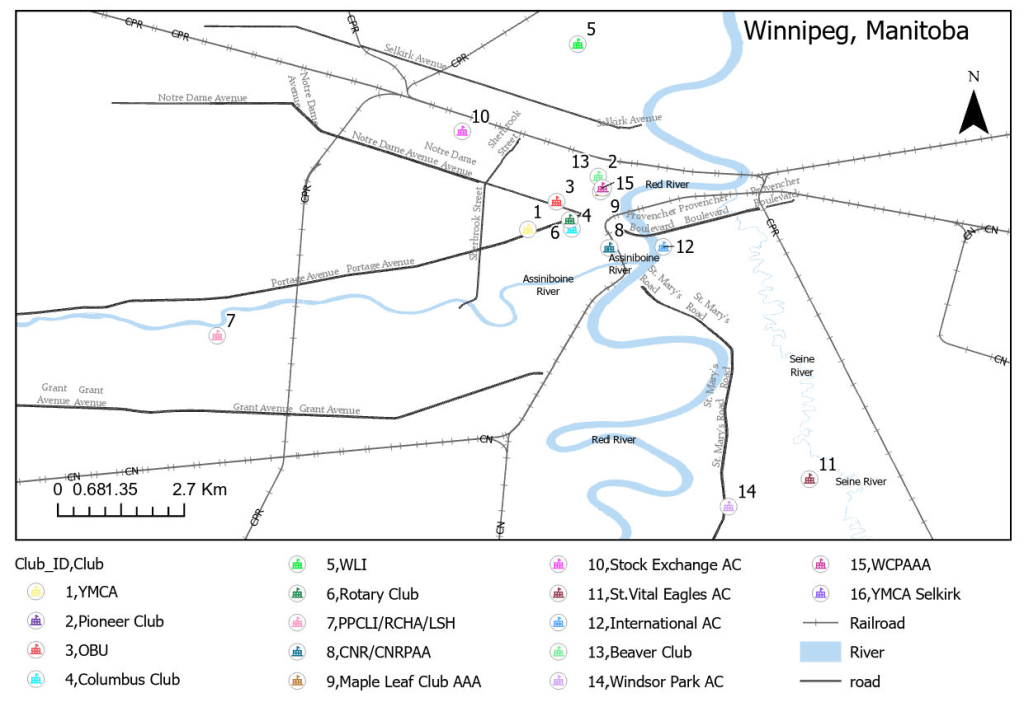

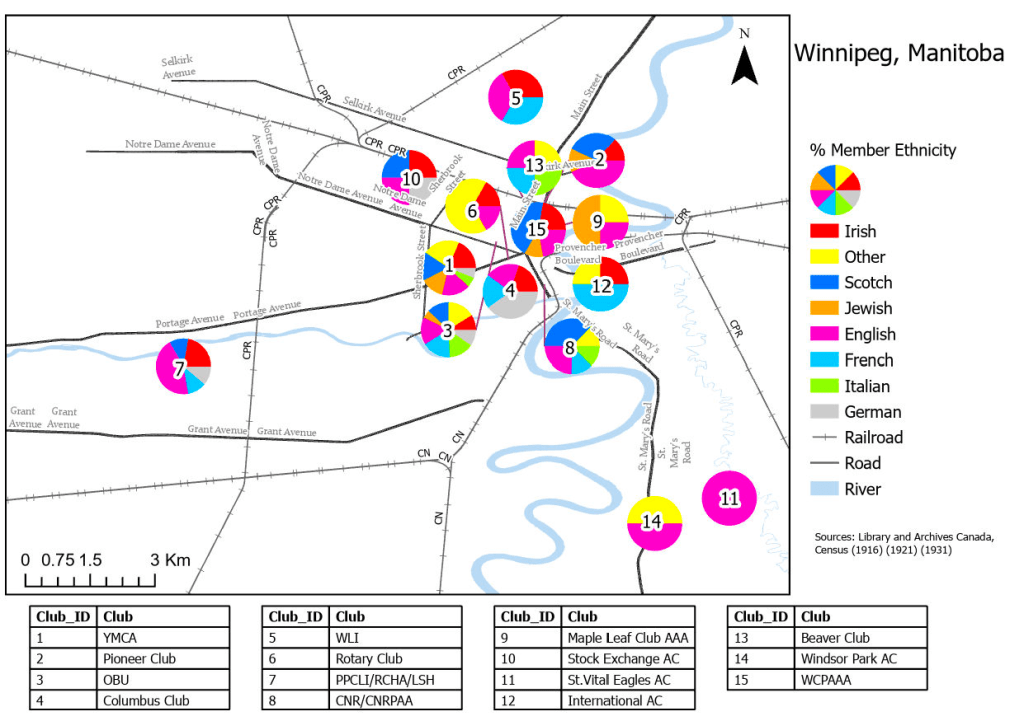

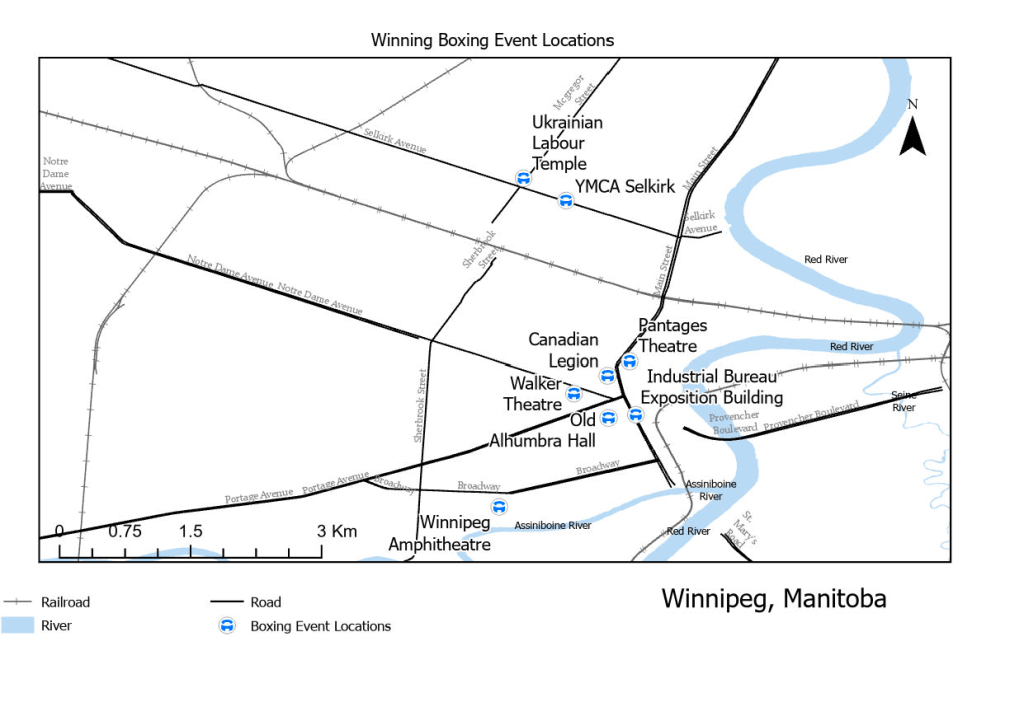

The map below (Figure 2) shows the distribution of over fourteen boxing gyms in the city, strategically located near transportation lines and embedded within residential and industrial areas. These gyms were easily accessible and within areas with the population density to support membership, making it convenient to organize events and competitions.

The data comes from 193 boxers, wrestlers, and individuals involved with the sport between 1924 and 1936. I found them and their gym locations from Winnipeg newspaper boxing cards and got their demographic information from three census reports, the National Censuses of 1921 and 1931 and the Prairie Census of 1926.

Many gyms in the city, such as the YMCA Gymnasium (featured image, at top), were touted as the most advanced in Winnipeg and North America. YMCA board members and The Winnipeg Tribune, a left-leaning newspaper in the city, were some of many that did this, as the One Big Union made similar statements. Boxing gyms were multipurpose and typically occupied one corner of a gymnasium, which also served as a basketball court, track room, gymnastics, and weightlifting room. As the image depicts, these gyms were revolutionary to the period. Swiss-ball training, gymnastics, and weight training were all new activities. Many YMCA reports showcase that gyms were insulated and provided modern restrooms, showers, swimming pools, cold plunges, and saunas.

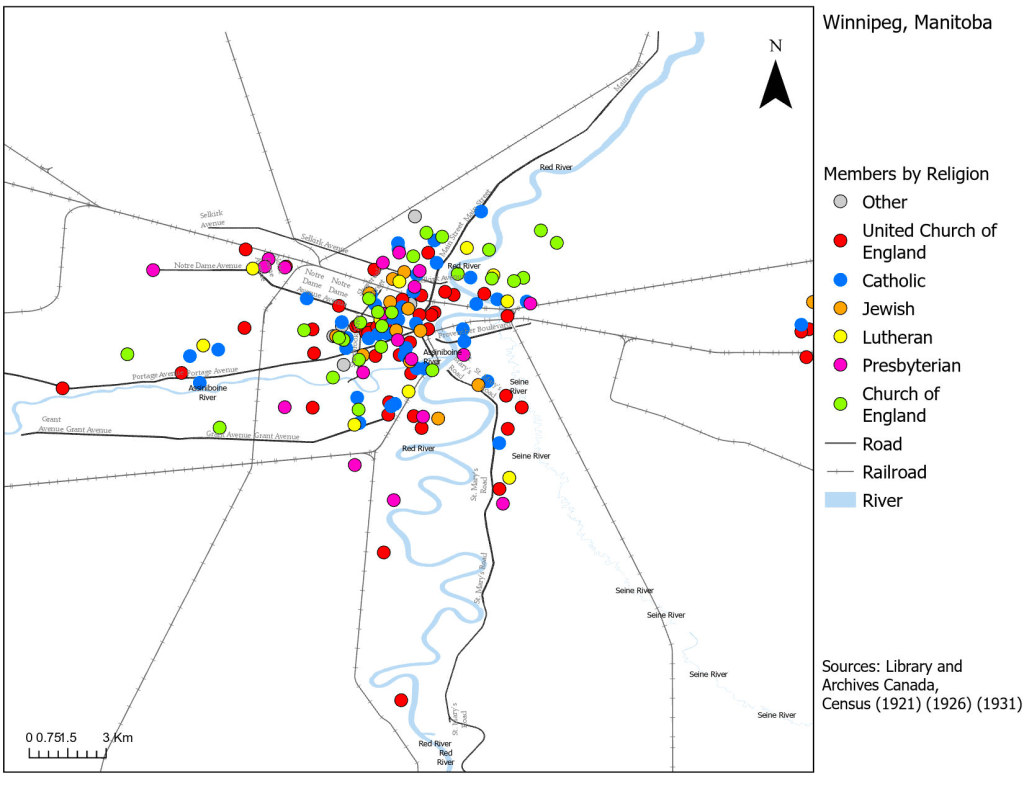

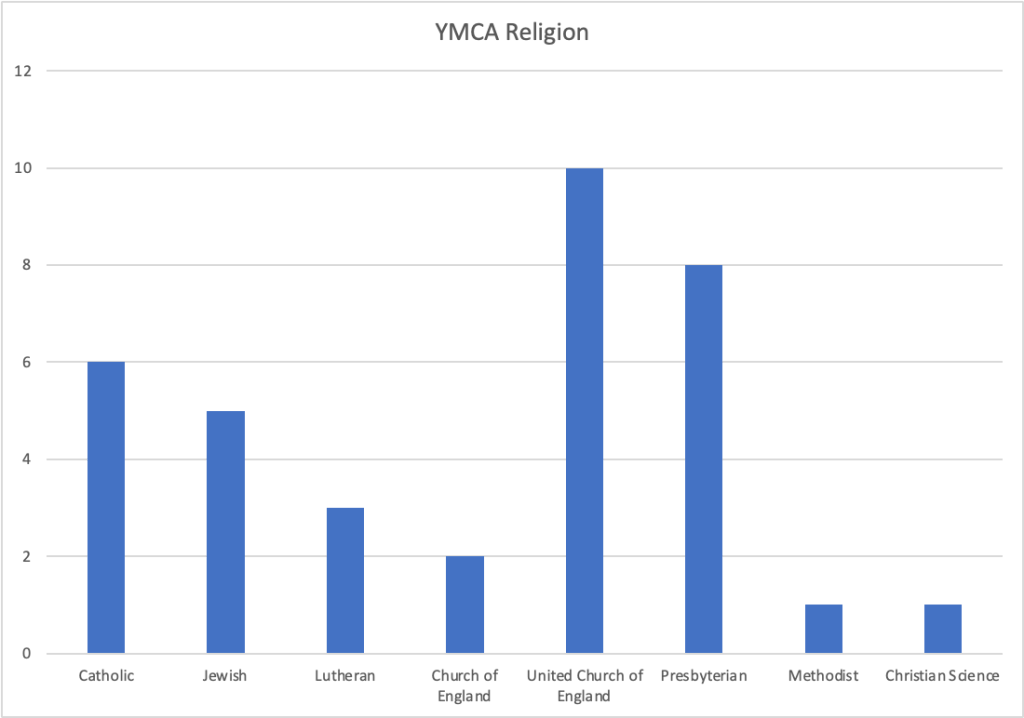

An analysis of the ethnic and religious composition (Figures 3 & 4) of the individuals reveals a diverse mix of backgrounds, most clustered in the Fort Rouge, West End, and Central districts shown in Figure 6. While a majority came from Protestant backgrounds, there was also participation by Catholics, Lutherans, and Jews, reflecting the city’s diverse religious landscape. While the maps illustrate this diversity, they do not highlight how these people met in third places, interacted, or how boxing events became multicultural. It demonstrates that city inhabitants were multicultural, but how did boxing manage to cater to all? The next series of maps shows the religious and ethnic diversity of each club.

Maps (Figures 5 & 6) show that specific gyms, like the YMCA, have catered to diverse religious denominations and ethnic groups over the years. (Figure 7). The YMCA map titled “What is a boy worth?” (Figure 1) was part of a membership drive. It shows Winnipeg divided into eight districts. The table below the map indicates the number of boys per district, which the author distributed by religious affiliation. The table highlighted that many boys belonged to the primary Anglo-Protestant affiliations, such as the United Church, Baptist Church, Presbyterian, and Church of England. However, there were also Jewish, Catholic, and Lutheran affiliations. The author advanced three propositions. First, “the membership of the Boy’s Department comes from all sections of Greater Winnipeg—here rich and poor mingle together on an equality.” Second, “out of the 1,068 boys, only 75 have no church affiliations.” Third, “tolerance of the views of others becomes an important factor in the development of the boy. Here the boy is taught, under all circumstances, to play fair with others and the value of team play—a sound foundation on which to build the super-structure of life.”[6]

This begs the question: Why attempt to cater to all social and religious classes, as the map’s author indicated? YMCA elected leaders, who came from the Anglo and Protestant majority, opined that their class, ethnic, and religious position made them natural city leaders. They considered that physical recreation was an excellent means to help masculinize the Anglo majority who, no longer working on farms, were in white-collar and non-labor jobs. Furthermore, they saw an issue with child delinquency and urban decay caused by immigration. They determined that sports supervised by ethnic and religious community members along with Protestant and British Isles men would safeguard boys from the dangers of the city.

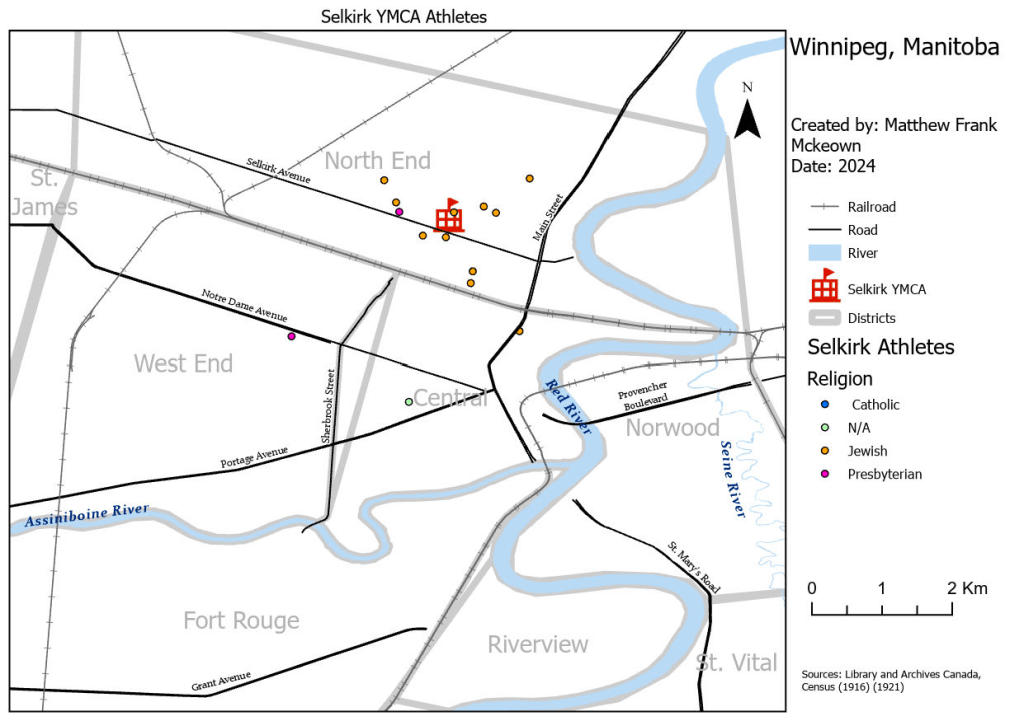

To help immigrants, YMCA staff created newsboy boxing and basketball events. Newsboys usually came from working-class families and were first-or second-generation immigrants; in Winnipeg, many were Jewish. Note in Figure 7 that most of the athletes competing in the boxing and basketball events lived in the North End near Selkirk.

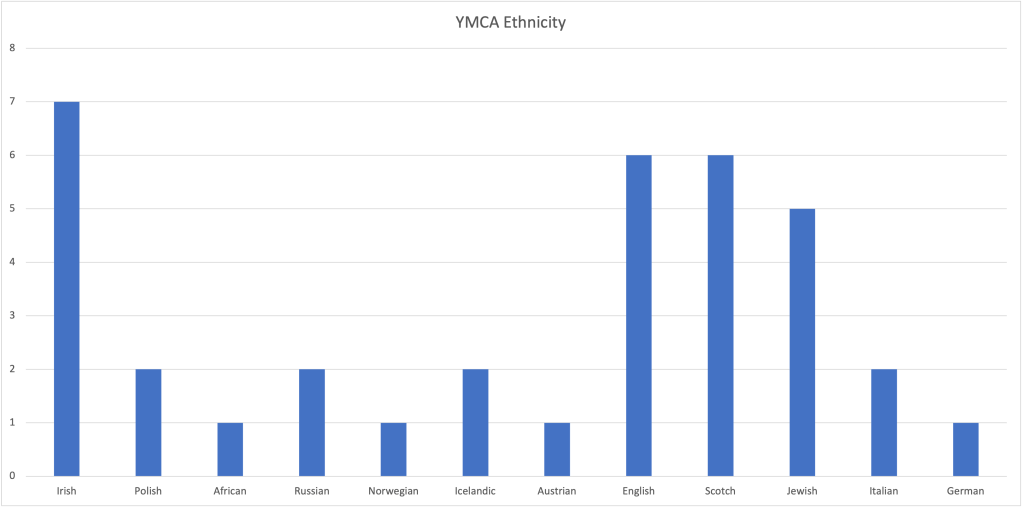

Along with helping Jewish newsboys, they had Jewish athletes on other basketball teams and baseball teams. As is shown in Figures 8 and 9, out of the thirty-six boxers, wrestlers, and members involved with the sport, 14 percent were Jewish. They were indeed not perfect, as they created a 5 percent capacity limit on Jewish members to curb the rise of Jewish applicants, which is an unfortunate example of how they segregated. Even after the creation of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), Jews still came to the YMCA, including David Dector, who boxed there in the 1930s; the YMHA did not have a boxing team.

Note the diversity of boxers at the YMCA (Figure 10), which can also be seen spatially, as members come from various city districts.

While most non-Anglos lived in the city’s North End, they would have travelled to the South End Vaughn Street location, an example of mobility. Also, note that some non-Anglos live in the South End. While this is a small sample of athletes who came to the YMCA, one notices that while most came from the city center, members came from all parts of the city. Nonetheless, the YMCA could only cater to some boxers in the city. While they did host boxing events, they could not host significant events as they needed more space. The YMCA boxers met boxers from other communities, who often had backgrounds different from theirs, through the many locations hosting boxing events.

The following map (Figure 11) shows the location of most, but not all, event locations. These places were near the city’s center, where most boxers and those associated with the sport lived. These were the places where different clubs could meet and diversify. Many of these events hosted over 500 people; city and provincial tournaments were announced in newspapers months before they took place. Winners became celebrities in the city, and the Winnipeg city or provincial tournaments created new opportunities for fighters to earn income by becoming professionals or attempting to make the Canadian Olympic team. These events created income for location owners and vendors, who received a license to sell their products. Furthermore, the buying of equipment supported local businesses. Profits went to organizations to help support their members, keep their clubs up-to-date, and assist injured and amateur fighters travelling across Canada and the United States. Also, annual events for charity purposes provided money and services to low-income city inhabitants. These events were designed with community development in mind, and for nearly twenty years, boxing experienced a golden age.

To curb the decline of third places and create spaces for community engagement, cities can consider various steps such as investing in community centers, urban parks, and recreational facilities, promoting local businesses, organizing cultural and amateur sports events, and providing support for community initiatives. Addressing the decline of third places and the deterioration of community in the urban environment may involve promoting a sense of community ownership, encouraging public participation in decision-making processes, i.e. creating non-traditional forms of civil society and creating inclusive and accessible public spaces that promote discourse within diverse communities. Urban revitalization through community engagement and promoting activities like boxing can potentially impact social cohesion, physical and mental well-being, and economic development. The YMCA in Winnipeg attempted to use boxing to remedy the decline of the downtown area. The YMCA example illustrates the beneficial effects of community leaders being able to think outside the box and explore non-traditional approaches to urban revitalization.

Matthew McKeown is a MA candidate in the history department of Trent University and also an owner of a small, community-based gym in Toronto. He is currently working on a dissertation about community and sports in Winnipeg during the twentieth century.

Featured image (at top): from The Young Men’s Christian Association of the City of Winnipeg, Twenty-Fourth annual Prospectus, 1902-03, YMCA of Winnipeg annual reports, 1895-1911, P3797/3 YMCA of Winnipeg fonds, Archives of Manitoba, 200 Vaughan St Room 130, Winnipeg, MB R3C 1T5.

[1] For his concept of the third place, see Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing Group, 2023). For a discussion of the connection of third places and community into Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of social capital, see Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2020).

[2] For more on the concept of community, see Craig Calhoun, “Community without Propinquity Revisited: Communications Technology and the Transformation of the Urban Public Sphere,” Sociological Inquiry 68, no. 3 (1998), 374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1998.tb00474.x; C. J. Calhoun, “Community: Toward a Variable Conceptualization for Comparative Research.” Social History (London) 5, no. 1 (1980), 106. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071028008567472.

[3] For more, see Craig Calhoun, “Imagining Solidarity: Cosmopolitanism, Constitutional Patriotism, and the Public Sphere,” Public Culture 14, no. 1 (January 1, 2002): 147–71.

[4] See Daniel Hiebert, “Class, Ethnicity and Residential Structure: The Social Geography of Winnipeg, 1901–1921,” Journal of Historical Geography 17, no. 1 (January 1991): 56–86.

[5] For example, see Mei-Po Kwan, “Beyond Space (As We Knew It): Toward Temporally Integrated Geographies of Segregation, Health, and Accessibility,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103, no. 5 (2013), 1082. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.792177.

[6] “What is a Boy Worth,” (1927), YMCA of Winnipeg Financial Material, 1922-1985, P3807/2 YMCA of Winnipeg fonds, Archives of Manitoba, 200 Vaughan St Room 130, Winnipeg, MB R3C 1T5.