This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Genna Kane

Bostonians grumbled and complained when the Sumner Tunnel closed again in the Summer of 2024, demonstrating the significance of underwater connections to East Boston. The City of Boston annexed East Boston in 1836, but the harbor strained East Boston’s connection to the rest of the city. By the late nineteenth century, businessmen and political leaders supported a new underwater tunnel for streetcar service. The East Boston Tunnel opened in 1904 and paved the way for the Sumner Tunnel in the 1930s.[1] Many historians understand infrastructure, including wharves, freight railroads, and passenger transportation, as facilitators for capital accumulation and consumption.[2] Historians also emphasize that infrastructure changed, as David Nye argues, when people made cultural choices “within parameters set by the energy sources, technologies, and markets of any given time.”[3] During the age of industrial capitalism, Bostonians reconfigured and bypassed the structures from the bygone era of maritime commerce and prioritized new infrastructure and connections.

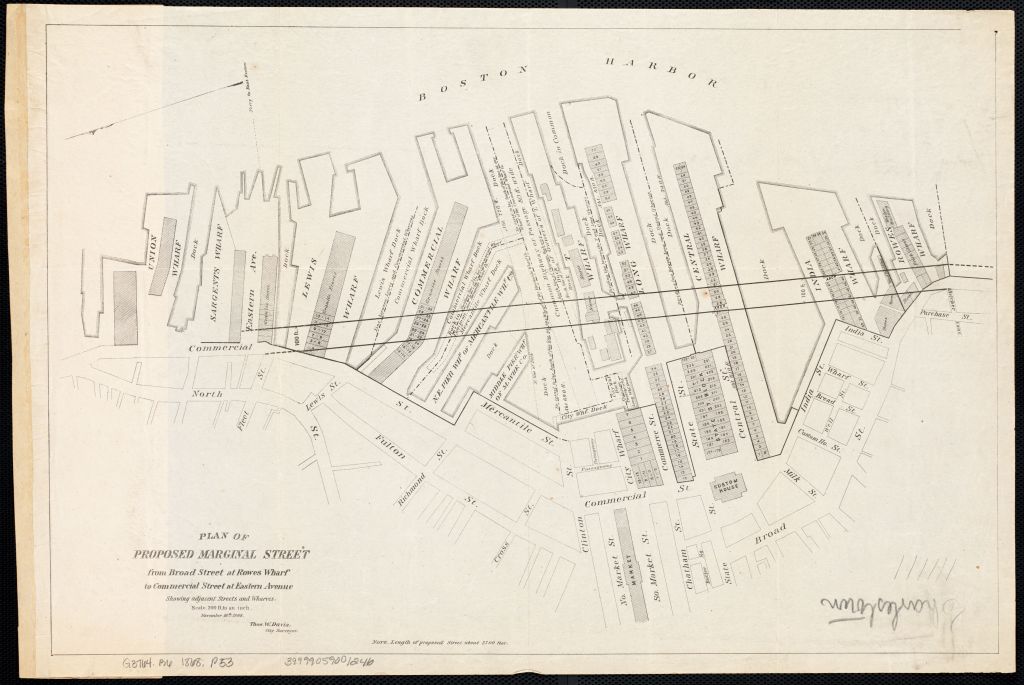

Boston was initially colonized as a port, but by the late nineteenth century, the waterfront’s infrastructure struggled to support industrial capitalism.[4] Throughout the eighteenth century, the center of Boston’s commercial life had grown at King Street because the Town House (now the Old State House) held the British Government.[5] Merchants built Long Wharf as a 1,562 foot extension of King Street into the harbor in 1715.[6] The Long Wharf to King Street thoroughfare emphasized that the Town House depended upon the physical connection to the waterfront.[7] However, Boston’s maritime port infrastructure languished by the late nineteenth century.[8] Boston relied on imports because New England did not have reliable and profitable exports, but fewer merchants in the age of industrial capitalism shipped freight through Boston’s waterfront, due to its geographic isolation and subsequently higher shipping cost compared to other ports.[9] Between the 1850s and 1870s, Boston’s registered shipping tonnage declined by nearly half.[10] In reaction, the municipal government replaced the downtown wharves with railroad tracks.[11] Between 1868 and 1872, the city built Atlantic Avenue to facilitate rail connections for the Union Freight Railway along the waterfront.[12] As Figure 1 illustrates, the city cut through the downtown wharves to construct Atlantic Avenue.

Meanwhile, developers and officials invested in infrastructure to accommodate the growing work opportunities and population growth from immigration.[13] Boston transformed from a “walking city” to a “streetcar city” after Boston annexed peripheral suburbs and incentivized companies to develop streetcar service.[14] To meet the increasing demand for transportation to the urban core, the waterfront’s proprietors adapted the downtown wharves for passenger service.[15] Individual railroad corporations also operated ferries in order to connect their passenger service across the harbor.[16] However, passenger ferries congested the harbor. Starting in the 1880s, East Boston businessmen concluded that the harbor’s congestion hindered an efficient connection to downtown and squandered opportunities.[17] As the East Boston Citizens Trade Association resolved in 1893: “A tunnel from Boston to East Boston is the only means through which [we] can obtain…the privilege now granted to all other sections of the city.”[18]

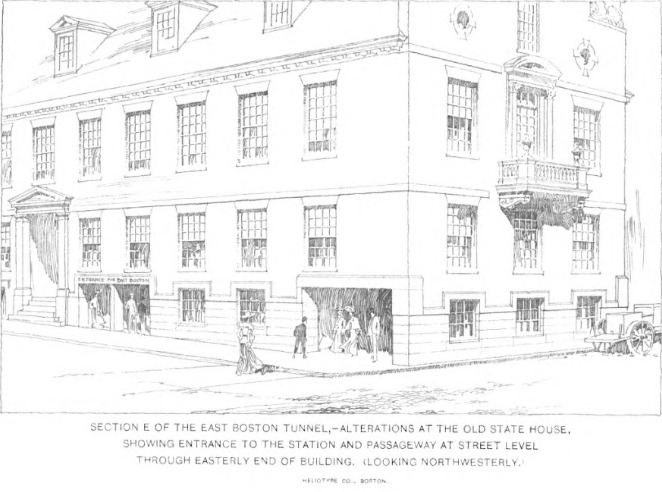

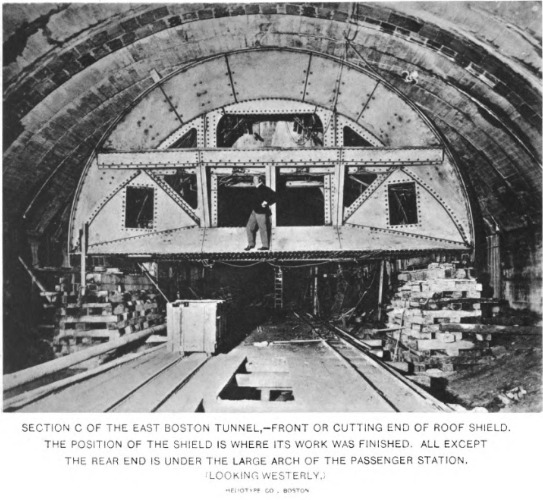

Spurred by businessmen, the state and city government supported the tunnel after the expansion of publicly-managed transportation.[19] After the state prioritized streetcar service as a public good rather than a private enterprise, the Massachusetts Legislature created the Boston Transit Commission (BTC) in 1894.[20] Supported by Representative John Bates of East Boston, the state permitted the BTC to construct the tunnel.[21] In 1900, workers relied on a roof shield and high-pressure air pumps, dug under the harbor by hand, and installed steel-reinforced concrete walls (see featured image, at top).[22] By 1903, the BTC completed the 5,280 foot tunnel between Maverick Square and downtown Boston.[23] The BTC routed the tunnel underneath Long Wharf and reconfigured the Old State House as the new Devonshire Street Station’s headhouse by 1904 (Figure 2).[24]

However, some Bostonians abhorred the Old State House’s new use. Colonial revival preservationists argued that the BTC “prostituted” the building.[25] At the turn of the twentieth century, the Brahmins, the elite class in Boston that claimed lineage dating back to the seventeenth-century Anglo-Saxons, advocated for preservation of colonial structures.[26] The Brahmins’ anxiety about Boston’s industrial and demographic changes, especially the large population of European immigrants that challenged the Brahmins’ political representation and authority, informed colonial revivalism as a means to maintain cultural dominance.[27] The preservationists and the BTC eventually reached a compromise by 1907 that kept the Devonshire Street station entrance in the Old State House’s basement but created museum space on the first and second floors (which is how the building functions today, to the surprise of many travelers).[28]

Some historians frame episodes like the East Boston Tunnel and the Old State House controversy within the dichotomy of “tradition” versus “progress.”[29] However, the Old State House hardly held the “traditional” way of life in Boston by the twentieth century—for most of the nineteenth century, the building displayed advertisements, housed eclectic tenants, and was nearly demolished by 1880.[30] The Brahmins invented the Old State House as a symbol of the colonial past at the moment they vied for cultural dominance. Even after the creation of museum space, the tunnel transformed the Old State House from the remnants of Boston’s mercantile and maritime order into a component of efficient infrastructure. John Bates (then the Governor) stated in his 1904 dedication of the East Boston Tunnel that the journey downtown took forty-five minutes, but after the tunnel, “I can now cover the distance in 15 minutes.”[31] The tunnel helped Bostonians achieve rapid transportation by bypassing the harbor entirely.

Genna (Genevieve) Kane is a PhD Candidate in the American & New England Studies Program at Boston University. Her dissertation focuses on the environmental and architectural history of Boston’s waterfront since the nineteenth century. She studies the adaptations of the waterfront and its recent configurations as a climate resilient space. Her work has also been supported by the University of California Berkeley’s Environmental Design Archives and the Boston Public Library Leventhal Map & Education Center, among others.

Featured image (at top): Plate 4, Annual Report of the Boston Transit Commission for the Year Ending 1903 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, City Printers, 1904),

[1] The East Boston Tunnel also accommodates the Blue Line’s service to this day.

[2] William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1992); Kathryn Lasdow, “Spirit of Improvement: Construction, Conflict, and Community in Early National Port Cities” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2018); Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011).

[3] David Nye, Consuming Power: A Social History of American Energies (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998), 10.

[4] Jonathan Levy, Ages of American Capitalism: A History of the United States (New York: Random House, 2021), 3, 10.

[5] Walter Muir Whitehill, Boston: A Topographical History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 8.

[6] Nancy Seasholes, Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 31.

[7] Lawrence Kennedy, Planning the City upon a Hill: Boston Since 1630. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), 18; G. B. Warden, “Inequality and Instability in Eighteenth-Century Boston: A Reappraisal,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History (Spring 1976): 585-620; Whitehill, Boston: A Topographical History, 20-21.

[8] As David Nye argues, “the tidewater cities and trading towns on the major rivers were not manufacturing centers.” Nye, Consuming Power, 70-72. See also: Marti Frank, “Water and Steam: How Industrial Power Shaped the New England Landscape,” in Blake Harrison and Richard W. Judd, eds., A Landscape History of New England (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 270–72.

[9] William H. Bunting, Portrait of a Port: Boston, 1852-1914 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), 9; Michael Rawson, Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 200; Seasholes, Gaining Ground, 295.

[10] William H. Bunting emphasizes that “in 1855, Boston’s total registered tonnage was 482,438; in 1870 it was 275,436.” Bunting, Portrait of a Port, 16.

[11] Dave Donaldson and Richard Hornbeck, “Railroads and American Economic Growth: A ‘Market Access’ Approach,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 2 (2016): 799-858; Levy, Ages of American Capitalism, 234. For the debates over railroads in the urban core in Baltimore, see David Schley, “Tracks in the Streets: Railroads, Infrastructure, and Urban Space in Baltimore, 1828–1840,” Journal of Urban History 39 no. 6 (2019): 1062-1084.

[12] For further reading, see: Robert A. Sauder, “The Use of Sanborn Maps in Reconstructing ‘Geographies of the Past’: Boston’s Waterfront from 1867 to 1972,” Journal of Geography 79, no. 6 (Nov. 1980): 206.

[13] Robert Fishman, Bourgeois Utopias: The Rise and Fall of Suburbia (New York: Basic Books, 1987); James O’Connell, The Hub’s Metropolis: Greater Boston’s Development from Railroad Suburbs to Smart Growth. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013), 69-73.

[14] Sam Bass Warner, Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston, 1870-1900 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1962), 15.

[15] Bunting, Portrait of a Port, 16; Rawson, Eden on the Charles, 200; Seasholes, Gaining Ground, 295. The East Boston Ferry Company operated in 1852 to East Boston’s Lewis Wharf, and the People’s Ferry Company offered service to East Boston’s Maverick Wharf. The City of Boston acquired and managed the People’s Ferry by 1864 and the East Boston Ferry by 1870. Passenger steamship companies most consistently used the wharves east of Atlantic Avenue. For example, Long Wharf housed the Boston & Philadelphia Steamship Company by 1874 and the Philadelphia Steamship Line by 1888. Bunting, Portrait of a Port, 154.

[16] One example was the Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad’s connection between Rowe’s Wharf downtown and East Boston. Bunting, Portrait of a Port, 154.

[17] “Its Eleventh Anniversary: Banquet of the Citizens’ Trade Association of East Boston,” Boston Daily Globe, 24 Jan 1884; “Tunnel To East Boston: Scheme Submitted by Engineer Herschel. It is Considered by the East Boston Citizens’ Trade Association,” Boston Daily Globe, 17 Jan 1888.

[18] “Under The Water: Noddle Islanders Want a System of Tunnels. Takes Too Long for Them to Go to City Hall,” Boston Daily Globe, 30 Mar 1893.

[19] “Common Council September 29th, 1892,” Reports of Proceedings of the City Council of Boston for the Year 1893 (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill City Printers, 1893), 824.

[20] More Bostonians relied on streetcar service by the late nineteenth century, and as more people moved to streetcar suburbs, the privately owned West End Railway failed to accommodate the demand for service. In reaction, the Commonwealth decided to incrementally regulate the railway system. O’Connell, The Hub’s Metropolis, 73. For further reading about the integration of utilities into municipalities and the growing conception of government services in this period, see Rawson, Eden on the Charles, 129-178.

[21] The act was called “An Act to Promote Rapid Transit in the City of Boston and Vicinity.” “Under The Water: Noddle Islanders Want a System of Tunnels. Takes Too Long for Them to Go to City Hall,” Boston Daily Globe, 30 Mar 1893; “East Boston Tunnel, Leaflet printed for the Boston Transit Commission, 29 December 1904,” (Boston, 1904), Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=6468.

[22] “Monster Shield Has Been Placed In The Shaft: It Will be Used in Boring Under the Harbor in the Work on the East Boston Tunnel,” Boston Daily Globe, 27 Dec 1900; Steven Beaucher, Boston in Transit: Mapping the History of Public Transportation in the Hub (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2023), 205.

[23] “Last Section Begun: Progress of Work on East Boston Tunnel. From East Side of Washington St at State to Scollay Sq. Contract Calls for Its Finish Next December,” Boston Daily Globe, 19 July 1903.

[24] Beaucher, Boston in Transit, 208.

[25] James Lindgren, Preserving Historic New England: Preservation, Progressivism, and the Remaking of Memory (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 44.

[26] Oliver Wendell Holmes articulated the phrase “Brahmin Caste” to describe the Brahmin’s elite status, akin to the Brahmin Hindu Caste system, where the Brahmin was the highest-ranking Caste. Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Professor’s Story: Chapter I: The Brahmin Caste of New England,” in The Atlantic Monthly V no. XXVII (January 1860), 93. See also: E. Digby Baltzell, The Protestant Establishment: Aristocracy & Caste in America (New York: Random House, 1964); E. Digby Baltzell, Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia: Two Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Class Authority and Leadership (New York: Free Press, 1979).

[27] Paula M. Kane, Separatism and Subculture: Boston Catholicism, 1900-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994); Lindgren, Preserving Historic New England), 6; Thomas H. O’Connor, The Boston Irish: A Political History (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995).

[28] Lindgren, Preserving Historic New England, 44.

[29] Lindgren, Preserving Historic New England, 43.

[30] Keith Morgan, ed. Buildings of Massachusetts: Metropolitan Boston (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009), 50.

[31] “East Boston In A Joyful Mood: Illumination, Parade And Banquet Mark Opening Of Its Big Tunnel,” Boston Daily Globe, 30 Dec 1904.

One thought on “Circumventing the Past: Navigating Around the Harbor Through the East Boston Tunnel”