On August 4, 2020, a massive explosion ripped through the heart of Beirut, Lebanon. While the devastation left by the blast was followed by a series of reconstruction efforts, it has remained difficult to document, map, and support the living heritage of the city, especially regarding its small creative businesses. The Living Heritage Atlas | Beirut project addresses this gap by documenting and visualizing Beirut’s living heritage of artisanship by mapping its craftspeople and cataloging its crafts through an open-source database, viewable through an interactive website.

This project celebrates the past and present of local artisanship through archival data, walking tours, and community workshops. By leveraging historical data and interactions with craftspeople, this project advocates for a more equitable future for small local crafts businesses as they cope with the ongoing economic crisis, post-disaster challenges, and fierce global market competition. In short, the goal of this digital atlas is to shed light on the intangible heritage of Beirut by highlighting the cultural significance of craftspeople and their potential role in crafting the future of the city from the ground up.

We spoke with Dr. Carmelo Ignaccolo, a Ph.D. graduate of MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning and an incoming Assistant Professor at Rutgers’ Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy. Carmelo served as the Lead Researcher and Project Manager for the Living Heritage Atlas | Beirut project, along with Canadian-Lebanese architect Daniella Maamari. The project’s Principal Investigators (PIs) were Prof. Sarah Williams from MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab (CDDL) and Prof. Azra Aksamija from MIT’s Future Heritage Lab. The project was generously supported by an MIT-Dar Group Seed Grant and managed by the MIT Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism.

How did this site come into being and what role did you play?

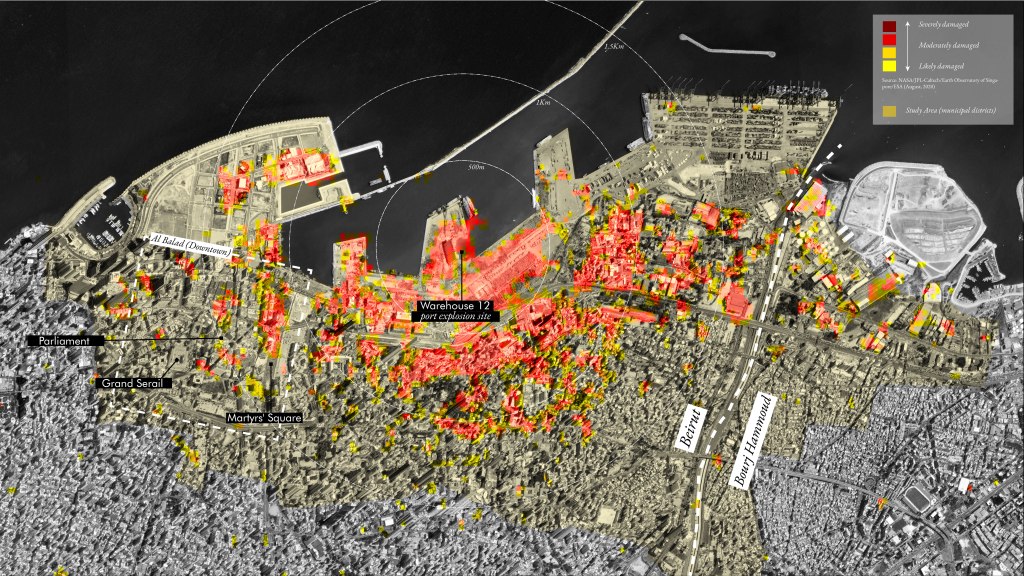

The Living Heritage Atlas | Beirut website is the result of two years (2020-2022) of rigorous archival fieldwork and community engagement activities in Beirut, Lebanon. Under the supervision of the project PIs, co-lead researcher Daniella Maamari and I planned and executed two key actions: an extensive on-the-ground mapping effort of operating crafts workshops and an archival data collection of images, newspaper ads, and old postcards related to crafts. As a research team, we decided to focus our investigation on the port-adjacent districts of Beirut, spanning from Al-Balad (the old town) to Bourj Hammoud (an independent municipality on the east banks of the Beirut River). The spatial definition is based on a geospatial analysis of the physical damages of the August 2020 port explosion. We quantified the percentage of damaged buildings at a municipal district level and structured our data collection effort accordingly.

With a team of approximately ten research assistants from the American University of Beirut (AUB) and the Lebanese American University (LAU), we mapped approximately 150 existing crafts workshops and geolocated more than 800 archival images of workshops gathered in more than fifteen archives in the city, including the Arab Image Foundation, the Sursock Museum Library, the AUB Library, and the Archive of the Ministry of Tourism.

To engage with the concept of heritage in a non-nostalgic way, we consider craftsmanship as a key component of Beirut’s multicultural and evolving identity. In fact, we decided to create a website that brings contemporary workshops into conversation with images of shops that no longer exist or have relocated within Beirut or even abroad. Upon entering the website, visitors can choose to view the data either spatially on a map or thematically by craft. In my opinion, the most effective visualization is the map-based one. By viewing the distribution of crafts workshops, visitors can notice spatial clusters of certain crafts, such as the aggregation of metal workers in the Karantina neighborhood. Each local business is color-coded based on the primary type of craft worked in that specific shop. By clicking on a business location, visitors can find photos and contact information of currently existing crafts workshops, along with historic images and captions describing the visual material and providing detailed archival references. Additionally, a time-based slider allows users to gain a longitudinal understanding of how small creative businesses in Beirut have relocated to more peripheral parts of the city over time.

As a designer, data scientist, and urban planner working at the intersection of urban history and spatial analytics, I worked with CDDL Researcher Ashley Louie on building the data collection survey and verifying each entry to build an accurate and queryable dataset. Given the complexity of the dataset, which includes images depicting craftspeople from the mid-late 19th century during the Ottoman Tanzimat to the early 2000s, it was challenging to structure a clear hierarchy and sub-hierarchy of crafts. Moreover, accurately geolocating images over time was particularly difficult in a city like Beirut, where radical urban design changes, contested masterplans, wars, and disasters have significantly altered the city’s urban form. For example, some early 20th-century streets no longer exist, and others have changed names throughout history. Thus, it was crucial to generate a survey with nested questions that allowed data collectors to select the map of the city as it was at the time the image was taken and try to geolocate the image with the highest level of accuracy.

I also gathered a series of historical maps and georeferenced them on the contemporary geography of Beirut to allow web visitors to interact with the layers of history of this ever-changing city. For example, the website hosts an 1876 map dedicated to the Ottoman Sultan Abul Hamid II, acquired through the online portal of the Department of Plans and Maps of the National Library of France in Paris. Other maps from the mid-to-late 20th century were physically obtained from the MIT Rotch Library and the Perry-Castaneda Library (PCL) Map Collection of The University of Texas in Austin. These included a 1945 map commissioned and drawn by the French Institut Géographique National (IGN) and a 1958 map prepared by the US Army Corps of Engineers for Operation Blue Bat, the US’ first-ever combat operation in the Middle East. Users can toggle these maps on and off and see the urban form of the city changing while moving the time slider to visualize the spatial relationship between urban form and business locations. A more analytical take on the urban form features extracted from historic maps and the presence of craft workshops over time is available at the following International Cartographic Conference abstract, I presented on behalf of the team in Cape Town in August 2022.

Finally, the Living Heritage Atlas | Beirut website is not only a tool to display the unmapped intangible heritage of the city but also a means to keep the dataset alive and growing by allowing visitors the add existing workshops and historical images of shops that might have been important landmarks for their communities over time. Given the dynamic nature of the dataset, we strongly believed in making the data points with their visual component open-access and easily accessible through the website to both inform policymakers and provide researchers with a one-of-a-kind longitudinal dataset on Beirut.

How did different audiences interact with the project? What were your goals for it ultimately?

The website and most importantly its unique geospatial dataset were crucial in initiating a series of community activities that culminated in a participatory mapping workshop and roundtable discussions on preserving and celebrating craftsmanship in the Abroyan Factories of Bourj Hammoud in July 2022. We decided to launch the website during this well-attended event. Daniella Maamari and Racha Doughman coordinated and curated a series of thematic panels with city authorities, international agencies, universities, NGOs, and craftspeople on 1) the importance of documenting craftsmanship, 2) the legal framework to protect cultural practices, and 3) the use of crafts in building inclusive public spaces.

Following these panels, over seventy participants were presented with detailed neighborhood maps of Beirut on which they could locate and name crafts workshops that hadn’t been previously located by the Living Heritage Atlas team. During this participatory “mapathon,” new locations were added to the online directory of existing workshops and the archival database, and attendees were provided with detailed instructions on how to keep adding new locations through the “Contribute” tab of the website. Additionally, craftspeople brought to the event a living heritage item of their choice (such as photos, maps, and fabric) that was scanned by our team and digitally located on the online atlas.

The enthusiasm generated by this event, which finally brought together various local, national, and international stakeholders in conversation with craftspeople in Beirut, led to a series of future initiatives that went beyond the initial scope of the project. UNESCO, for example, showed interest in the project, defining it as an innovative “tool to safeguard heritage.” Their interest in the unique dataset aligned with a large cultural business grant initiative aimed at identifying local shops that could potentially benefit from micro-grants to support their business in times of crisis. It was incredibly rewarding to see how newly created datasets could be useful for these concrete on-the-ground activities. Moreover, the momentum and public attention generated by this project—with extensive press coverage in Lebanon—around the theme of craftsmanship became part of a growing interest in mapping intangible heritage. It was inspiring to see parallel initiatives emerging in Beirut through NGOs and local entrepreneurs. On a more individual basis, some craftspeople showed interest in keeping their contact information and images up to date to increase their visibility through the online platform of the Living Heritage Atlas.

Finally, the images and locations collected in Beirut around the theme of craftsmanship were exhibited during the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale in the exhibition titled “Tools for Rebuilding Beirut.”

Where does this project fit into the larger universe of the digital humanities?

The Living Heritage Atlas is both an unprecedented collection of unmapped archival images and an advocacy tool. It supports web visitors and researchers in understanding the urban transformation of Beirut through the lens of craftsmanship, while also encouraging a critical reading of the enforced marginalization that has impacted small businesses, depriving them of their shops and public spaces and pushing them out of the city core. In other words, this project bridges the rigorous work of spatializing historic images in relation to urban landmarks over time (such as the work carried out by the team of “levantCarta” at the Spatial Studies Lab of Rice University) with the equity-driven, open access investigation of “Mapping Inequality” by the University of Richmond, which focuses on redlining and its enduring legacies. It does so through what Prof. Karilyn Crockett defines as the process of “hacking the archives”: a method of engaging with ordinary artifacts such as newspaper ads or postcards to bring back on the map those communities that were often unrepresented and therefore excluded from city-making practices. Because of its commitment to open data, the Living Heritage Atlas was recognized with an honorable mention at the 2022 edition of the “The MIT Prize for Open Data,” presented by the MIT School of Science and the MIT Libraries to inspire the next generation of researchers across the Institute. Through this work, the incredible potential to enrich the often-political lines of colonial maps in the context of Lebanon becomes evident, revealing the intricacies and richness of urban life that are often forgotten and left invisible. By making visible these often-informal and graphically silenced practices—such as those of creative crafts workshops—we uncover a new form of urban history. This history is generated and read from the ground up rather than through the perspectives of political authorities. I like to think of this as a critical and evolving process, as there will never be a perfect database on craftsmanship. This speaks to the mutable and dynamic nature of cities and the new ways in which digital tools can contribute to these participatory atlases. They will never be a finished product but will instead reflect the ongoing complexity of cities.

In conclusion, within the universe of digital humanities, the Living Heritage Atlas acts as a “comet,” with its tail crossing the “constellation” of digital humanities projects on historic images of urban change and the “constellation” of open-data portal viewed through justice and equity lenses.

Where do you see digital humanities going in the future?

As new digital tools and AI reshape the world of digital humanities by providing researchers with an unprecedented capacity to handle larger datasets and streamline innovative visualization tools, I believe the real challenge for the digital humanities world is to become…less digital and more physical! By this, I don’t mean going back to traditional archival research, but rather not seeing the creation of a website as the end goal of a digital humanities project. I believe that as scholars in this exciting and interdisciplinary field, we need to think about building seamless interactions between the digital and the physical by bringing our work out of bidimensional screens. To me, in fact, it remains critical to open up new datasets to researchers, activists, and people interested in specific topics and make digital material available in the public realm.

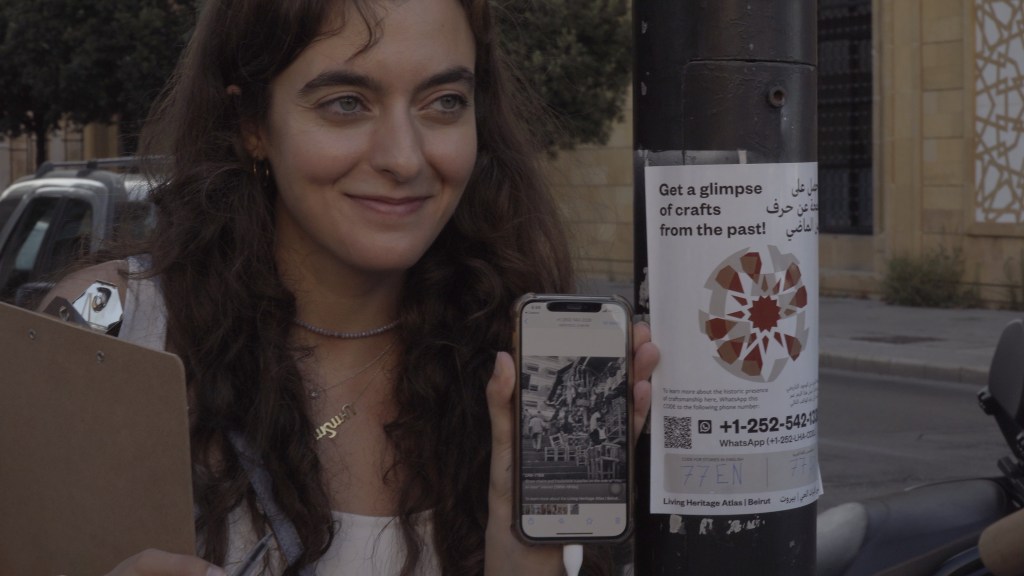

In the Living Heritage Atlas project, for example, we organized a series of neighborhood walks to visualize the historic images available on our website in the public realm. Under the slogan “Get a glimpse of crafts from the past!” we distributed a series of stickers (some of them with glowing paper to shine overnight) through which locals or visitors could start an interactive WhatsApp conversation with a craftsperson from the past who used to have their shop in that specific location. As a team, we curated these walks by creating an ad hoc map with the sticker locations. It was quite galvanizing to see these stickers being used by local tour guides to provide visitors with an additional level of history that was hard to see without our on-the-ground intervention. Moreover, by securing a physical component to the project, we managed to maximize outreach and keep engagement with the platform quite high. In short, these stickers act as digital windows into the city’s past.

In addition to the stickers, we curated a series of Craft Workshop Tours to learn about local crafts and their stories. During a Craft Workshop Tour, participants walked around the streets of Gemmayze, Mar Mikhael, and Bourj Hammoud to meet local endangered and unrecognized craftspeople on an intimate scale, shedding light on their unique practices and getting familiar with their know-how. These events, which run throughout July 2022, hosted 15 individuals at a time to maximize the learning experience and allow for personal connections between the craftsmen and the participants.

In conclusion, these examples illustrate what I believe is the responsibility of digital humanists today: to extend our projects beyond computer screens and enable them to function as tools to shed light on untold stories, reinterpret urban history through different perspectives, and promote more inclusive and equitable urban spaces.

Dr. Carmelo Ignaccolo is an urban designer, city planner, and spatial data scientist. He has recently obtained a doctoral degree in urban planning, design, and technology from MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. Carmelo will soon join the E. J. Bloustein School of Rutgers University as an Assistant Professor of Urban Planning and Policy Development. His research agenda focuses on urban design, spatial inequalities, and climate resilience.His research has been published in peer-reviewed journals and his digital mapping work has been featured in The New York Times and Bloomberg CityLab. Additionally, he has exhibited digital representations at Architecture Biennials in Seoul (2019), Shenzhen (2020), and Venice (2023).

Featured image (at top): Beirut, general view. between 1898 and 1914, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.