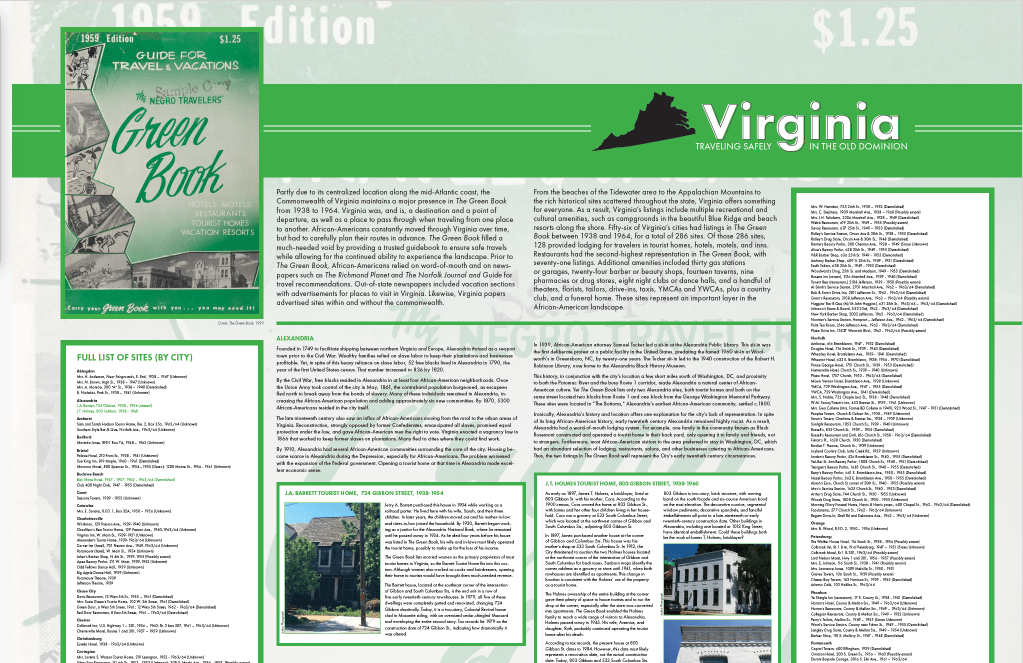

During the summer of 2016, architectural historians Anne E. Bruder, Susan Hellman, and Catherine W. Zipf came together over their shared interest in documenting the history of The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, more commonly referred to as simply “the Green Book.” As noted in their interview below, a series of conference engagements led to the realization that both the general public and academics shared an interest in excavating and highlighting the national history of The Green Book. With that knowledge in mind and the determination to map out this history before it vanished, the three historians launched the digital humanities project, The Architecture of the Negro Travelers’ Green Book. We sat down with Bruder, Hellman, and Zipf to discuss the history, present, and future of the project.

The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, more commonly known simply as the Green Book, has received increased attention over the past few years. Why do you think it’s become such a touchstone for folks and why did you choose to focus on it for a digital humanities project?

These are really two different questions for us. Regarding the question of the Green Book as a touchstone, this history resonates with many present-day issues—Black Lives Matter, equity in the environment, etc.—and hits hard at what we understand American values to be. Movement through space, the freedom of the highways, and enjoying the greatness of the American landscape are all qualities we hold dear. For example, in small towns like Hagerstown, MD, where Willie Mays played his first professional baseball game for the Trenton Giants (the then New York and eventually San Francisco Giants’ farm team) in June 1950, he had to stay at the Harmon Hotel on Jonathan Street, the only African American hotel in town. The idea that free movement through space was restricted challenges the fundamental nature of what it means to be an American, and ties strongly to other conversations we’re having in the public sphere.

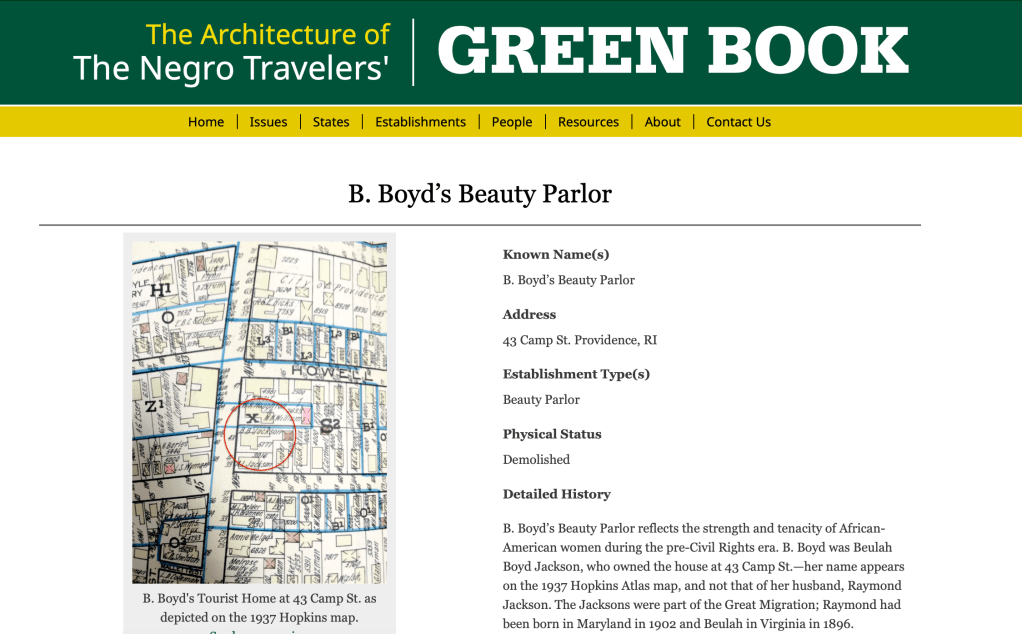

As to how we chose this project, it’s actually the other way around—this project chose us. Not long after the Schomburg Center at the New York Public Library announced in early 2016 that they had digitized their collection of Green Books, Catherine used their information to write an article for The Providence Journal on the MA Greene Tourist Home, in Providence. Seeing the article on social media (we three are longtime friends), Anne expressed interest in knowing more about Green Book buildings in her home state of Maryland. The two responded to a call for papers for a poster session at the Southeast Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians (SESAH) and in the process of putting those posters together, were joined by Susan and then by teams in North Carolina and Mississippi. At that conference, unexpectedly, we were inundated with other scholars wanting to do similar research in their own states. With their help, the project evolved into an effort to document the history and status of every building listed in The Negro Traveler’s Green Book across the country. This project and the grassroots community behind it is dedicated to that effort.

From the beginning, we knew this project needed to have a public, online component. But the intricacies of our findings made just “making a database” very tricky. Whatever database we constructed needed to accommodate what could be fifty different approaches to the topic—and account for many hours of professional programming. As three unaffiliated scholars, our pocketbooks were limited. With Anne (in charge of researching Maryland), Susan (Virginia), and Catherine (RI) operating as the “brain trust” of the project, we investigated StoryMaps, GIS, Google maps, WordPress, and many, many others, to a dizzying extent. After considerable research, we asked Worthy Martin, Ph.D., Director of the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (IATH) at the University of Virginia, to partner with us. Dr. Martin has proven to be a valuable contributor and has furthered our project considerably.

What is the biggest challenge you’ve faced on this project so far?

At the top level, the biggest challenge is determining how to do research in each of the states. In some cases, we’ve been lucky to have a self-directed scholar capable of finding and documenting sites. In others, we’ve assembled and managed a team. We’ve piloted a lot of models for this part of our project, but ultimately, it comes down to the lay of the land in each state. What works in one state may not work in another.

On the ground, our biggest challenges are finding the sites and keeping ahead of demolition. In many cases, there just isn’t enough information about where a site was—for example, “Rural Route 2” has no known street address and while the U.S. Postal Service has Rural Route maps, those do not provide mailbox locations. As another example, the Green Book sometimes listed locations in terms of directions, like “8 miles outside of town.” Again, today, this is difficult to find. Furthermore, while Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps are available for many cities and towns—which are very helpful for when urban renewal radically altered street patterns—African American neighborhoods were not always included. Misspelled names and streets also create problems in figuring out where a site was located. Additionally, it is difficult to keep ahead of the demolitions. Susan has found many instances where buildings that she surveyed just a few years ago are now gone. Keeping track of what is still standing, which is a key part of the information we’re trying to capture, remains an ongoing challenge.

In creating a national project, how have you determined which states to begin with? What are the factors in making these decisions?

We’d love to tell you that there is some science behind these decisions, but selecting which state to work on is a very organic process. We started with Maryland, Rhode Island, and Virginia, because that is where we live. At the SESAH conference, we were approached by scholars in Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Tennessee, and West Virginia and at subsequent conferences, by teams in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Texas. We are often contacted when we do an event (conference, local talk, etc.) and/or post an announcement on social media. And from time to time, we’ve used our professional contacts to recruit; for instance, we reached out to the Utah and Idaho State Historic Preservation Offices for information about sites in those states. But it takes time; not every effort works out, and we still have a long way to go.

How do you envision audiences interacting with the project? What are your goals for it ultimately? For example, have you had conversations, email exchanges, comments about this usage?

Our initial hope was to reach four communities: scholars interested in doing research on these sites, preservation professionals interested in preserving local history, armchair travelers interested in learning more about the Green Book itself, and people who lived the history. We hear regularly from users who volunteer information from their own family history or personal knowledge—or who want to tell us that what we’ve listed isn’t right (that happens too!). We are truly grateful to hear from them and we make these corrections/additions as quickly as possible. Given the volume of these inquiries, we feel we are doing a good job of reaching the general public and the people who lived the history. This audience is arguably the most difficult to reach, so it’s gratifying to know that they see our work and feel their participation is welcomed.

Engaging with scholars cuts both ways—we interact with researchers doing work to contribute to our database and with researchers using our data for their own projects. We’ve given a lot of thought to how to structure our database. With Dr. Martin’s and IATH’s help, we have crafted both a useful and a user-friendly database that tries very hard to match the realities of our research with the questions users might have or information we might find, all of which is no small task considering that every state’s Green Book listings are different. On the back end, Martin designed a template that allows each researcher to enter data uniformly, ensuring consistent presentation of the data regardless of a site’s location. This template enables our growing team of researchers to capture a wide range of information in the database.

On the front end, users are able to interface with the data from multiple perspectives and can search for owners or visitors, types of businesses, and/or locations at street, town and state levels. Want to see the sites on a map? You can do that. Interested in owners? There’s a way to search for them. In short, we’re working hard at anticipating how future scholars might need to use our data and building those functions, from scratch, right into the database. Once in a while, we get an unexpected request—for example, we were recently contacted by a medical research team from Columbia University looking to study the impact of structural racism on cognitive health, which is, obviously, not a function we envisioned for our project. It’s really interesting to see what others can do with the data from our project.

What has most surprised you about this project? Has it confirmed your prior ideas, changed your viewpoints, or some combination of both?

Speaking for just the three of us (because our researchers have had their own lightbulb moments), the biggest story is the continued disinvestment by owners as well as local, state and national governments. Many would expect that urban renewal or highway construction would be the primary factors—and they are major factors, without a doubt—but systemic/structural racism by officials and indifferent owners has also been a real issue. African Americans were as motivated as whites to move to larger cities to obtain better opportunities for themselves and their families. The losses of commercial ventures and a healthy population from historic neighborhoods reflect the structural racism found in African American neighborhoods in many American cities.

We’ve also been surprised by how ephemeral this history is. There is no way to know a site was listed in the Green Book unless you read the Green Book. While many Green Book sites survive to tell the history, without the artifact itself, those sites are just sites. The publication itself is what unites all these sites together into a landscape. That’s both quite powerful and quite fragile. We hear often about how people threw away their Green Books for newer versions or when the Civil Rights Act passed because they believed their Green Books were no longer needed (for those who remember, give thought to the last time you kept last year’s phone book). We could have very easily lost this history entirely.

Where does this project fit into the larger universe (galaxy?) of the digital humanities?

One unique thing about “The Architecture of The Negro Travelers’ Green Book” is that it is grounded in real-world problems. While we didn’t initially set out to make this database, the continued interest in our research and our own positions as practitioners and historians in the field (and not in academia) meant that we valued the practical applications of our work. This is not a project for the sake of a project; it is intended to be a tool for research of all kinds. We especially want to have an impact on the preservation of these sites. Beyond Virginia, many Green Book sites are now finding their way into National Register nominations and other preservation toolkits—we are proud of successes in Arkansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Rhode Island, and Virginia, to name just a few efforts of which we are aware. Specific examples include:

A resurvey of the Pleasant Street Historic District, in Hot Springs, AR

The addition of many Baltimore Green Book sites to the “Old West Baltimore” National Register nomination and the Civil Rights in Baltimore Multiple Property Documentation Form 1831-1976

The addition of Green Book sites to the “College Hill Historic District” National Register nomination, Providence, RI

Virginia’s efforts to marker program for Green Book sites

Where do you see digital humanities going in the future?

Advancing technology continues to open doors for new types of research, making possible what wasn’t possible before. It also engages new people in the “production” of history. Many people are interested in the past but are not “historians” and aren’t sure how to discover their history (despite how interesting the Ancestry.com ads make it look). When they come to our site and discover that we have information about a place and the people (usually a relative) they knew, they write to tell us. But we’re also interested in using technology to make this history accessible. We don’t want to be an information warehouse, but to be an interactive public history site for many users. And not to be too modest, but we hope our project has a long lifespan and that it continues to be of use to many generations of scholars. Like you, we can’t wait to see what future scholars see and make of our work.

Anne E. Bruder is an architectural historian based in Baltimore MD. She specializes in the history of Maryland, with a particular interest in the twentieth century history of suburban development, transportation, and African American travel. Since 2016, she has served as a co-founder of The Architecture of the Negro Travelers’ Green Book.

Susan Hellman has a BA from Duke University and an MA in Architectural History from the University of Virginia. In addition to The Architecture of the Negro Travelers’ Green Book, she works as a Principal Planner in the City of Alexandria, Virginia, Department of Planning & Zoning Historic Preservation division.

Catherine W. Zipf studies the underdogs of American architectural history, with a focus on race and gender. Recent projects include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and The Architecture of the Negro Travelers’ Green Book. By day, Zipf serves as the Executive Director of The Bristol Historical & Preservation Society, in Bristol, RI.