If you’ve been to Los Angeles recently and had the opportunity to visit the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), perhaps you were able to drop in on its new exhibit, “Ed Ruscha/Now Then“. Ruscha has long been an observer of the city, especially with regard to its vernacular and commercial architecture. While the LACMA exhibit focuses more on his paintings and print work, Ruscha is also famous for his photographic documentation, spanning five decades, of one of L.A.’s most iconic throughways, Sunset Boulevard. A new digital humanities project called Sunset Over Sunset (SOS) has embarked upon digitizing and exploring urban change along the boulevard, and by extension, the city itself over half a century. We sat down with its three founders, Francesca Russello Ammon, Brian Goldstein, and Garrett Dash Nelson to discuss SOS and its trajectory.

When and how did Sunset Over Sunset (SOS) come into being and what role did you all play in its development?

Sunset Over Sunset has deep roots in the images that have long underpinned Ed Ruscha’s artistic practice. A painter, printmaker, filmmaker, and photographer, Ruscha made his name in the 1960s in part with a series of books that examined common but overlooked forms of the American built environment, including gas stations, apartment buildings, and parking lots. One of those, Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966), depicted both sides of the most famous mile-and-a-half of Los Angeles’s Sunset Boulevard. While that project became well known, what remained largely unknown was that Ruscha continued to visit and photograph the entirety of Sunset’s twenty-five miles over the next four decades. In total, he visited Sunset twelve times and also photographed many other major LA streets, including Melrose, Hollywood Boulevard, and the Pacific Coast Highway. In 2012, the Getty Research Institute acquired this archive of more than 500,000 images and, after digitizing many of them, in 2018 the GRI issued a call for researchers to propose projects using what they then deemed “the most significant artistic attempt to record the urban fabric of a city in the postwar era.”

We have all been interested in Ruscha’s photographs as works of art but as urban historians we were especially intrigued by the instrumental possibilities of this amazing archive as a decade-by-decade record of urban change–-and precisely the kinds of changes that are elusive in typical archives (think of something like changing signage, or a modest renovation of a storefront, or the growth or removal of a street tree). We proposed a digital project that would bring together a number of these panoramas but also the other kinds of data that could illuminate what’s going on “behind” the facades, like demographic data from the U.S. Census, business directories, and newspaper articles. While we were interested in using the archive for our own work, we were especially excited about creating a fun and easy-to-use tool that other urban historians could also employ to explore any of the limitless research questions the photographs could answer.

We were extremely fortunate to be chosen by the GRI to pursue this goal as one of a handful of groups with initial access to the digitized images. We have benefited from GRI’s enthusiasm and support throughout the last six years as we have developed the site as a more analytical and scholarly complement to the two sites GRI has developed for Ed Ruscha’s “Streets of Los Angeles” archive: a playful image viewer, called 12 Sunsets, and a research portal, which functions as a digital analog of a traditional archival repository. Together, the three co-directors have guided the project during this long, sometimes unpredictable process (the pandemic was no help!), a task that has involved prototype development, coding, editorial work, grant writing (we applied for and were awarded an NEH Digital Humanities Advancement Grant in 2020), and lots of project management. All of this work would have been impossible without the collaboration of Rob Nelson, director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of Richmond, who took on the development of our site as a freelance project. His expertise with digital humanities and patience with an inherently complex data set (and with us!) brought Sunset Over Sunset to reality.

What’s your elevator/cocktail party pitch when explaining SOS to folks who are unaware of it?

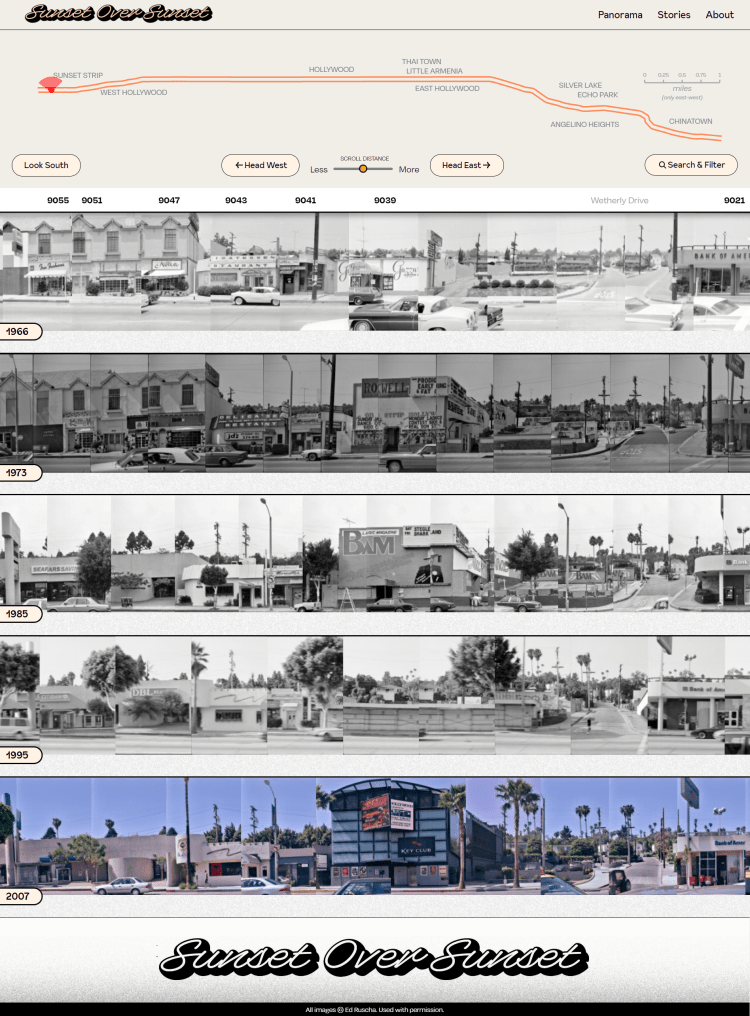

What can you learn about a city just by looking at images of how it has gradually changed over time? Answers to that question have remained only speculative, as no such year-by-year comprehensive record has been known to exist in the decades before Google Street View. But artist Ed Ruscha created just such an archive. Sunset Over Sunset makes it accessible to urban historians by stitching together and juxtaposing thousands of images that Ruscha took along ten intensively commercial miles of Sunset Boulevard in five different years across five decades (1966, 1973, 1985, 1995, and 2007), and combines them with the kinds of address-specific data that can help further describe what the images illuminate. A series of engaging, short essays on the site model the possibilities of this unique resource to answer research questions on everything from the history of Thai immigration to the rise of multinational corporations in the age of globalization.

SOS combines mapping, narrative, and photography to construct the history of Sunset Boulevard driven by the photography of Ed Ruscha, but it’s not just about the visible history of Sunset. SOS also offers more nuanced observations about what Ruscha was capturing intentionally, and in other moments, such as Max Böhner’s essay on its LGBTQ past or AnnaMarie Kooistra’s article on sex workers, perhaps unintentionally. How did you come to identify these sorts of issues and histories in his work?

A lot of this was just about realizing, through our own diverse interests, that there are a ton of questions one can answer here, but that one needs different kinds of lenses to see and ask them. We did put on some of those lenses ourselves but also thought it would be fun and illuminating to invite in a bunch of other people who would see the images in fresh ways–people not necessarily familiar with Ruscha, but who have the skills to see what may not be visible to every viewer. Both queer spaces–-in eras of intense repression–-and sex work characterize this kind of unseen: neither could be seen and still persist, yet both depended fundamentally on urban spaces like this one for that persistence.

In other words, a bar like the Black Cat (3909 Sunset Boulevard), which served queer patrons, or the Hollywood Call Board (6000 Sunset Boulevard), an answering service active in the business of prostitution, required urban locations that were accessible yet inconspicuous. In both cases, they eventually became visible to police: the Black Cat was the site of a 1967 police raid that sparked an early demonstration in support of gay rights; the Hollywood Call Board was raided in 1965. But these sites remain largely invisible in Ruscha’s images except for those who know where to look. We didn’t know about either one of them when we started this work, but Böhner and Kooistra, like other authors on Sunset Over Sunset, brought just such expertise to Ruscha’s photos. We envisioned this as a collaborative project, but essays like theirs really embody the exciting potential of collaboration beyond even our initial expectations. So, to answer the question directly, it’s fair to say that we did not identify these and other cases of the invisible so much as we benefited from the insight of the different eyes that people bring to these really rich photographs–-in their ability to read the signs, as it were–-and we sought to create a platform from which they could and can do that work.

Obviously, SOS offers a photographic history of Sunset Boulevard’s architecture over the years. Margaret Crawford and Alexander Tarr’s pieces speak to this most directly, but so does Mark Padoongpatt’s essay which explores the boulevard’s place in Thai Los Angeles, and manages to both discuss this ethnic history while placing it in dialogue with Sunset’s vernacular architectural past. What do the changes in architecture in these articles, and in Ruscha’s photography more generally, tell us about Ruscha?

Ruscha is closely identified with the oft-called “deadpan” view of architecture that he deployed in his books. As much as books like Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), which captures that type across Route 66 between Los Angeles and Oklahoma City, and Every Building on the Sunset Strip involve geographic dynamism, they also embody a quality of temporal staticity. They are photographs of specific sites at a specific moment in time, not over time. The amazing revelation of Ruscha’s frequent transits across Sunset, which we try to capture in juxtaposing five panoramas in Sunset Over Sunset, is that he was thinking about change over time all along. Indeed, he was fascinated by the idea of a city and its architecture changing. Rather than deadpan, static images, these photographs were really stills in a decades-long filmic recording of a city as its people shaped its buildings (Ruscha even took these photographs on movie film, not standard photographic film).

There’s a 2003 interview of Ruscha by Doris Berger (in the book Within, Alongside, and Between Spaces) that we found really helpful as we developed this project. “Do you compare the different versions and the state of changes?” Berger asked him. Ruscha replied, “Yeah, but mainly the idea is to get them down on film. I do the comparing later when I have got more time.” We liked seeing this idea of comparing as Ruscha’s intention all along–of understanding a city as in flux and dynamic. For us, this helped reframe how we thought about the valence of his images. At the time of Every Building and the other books, there were debates about the politics of what Denise Scott Brown called the “nonjudgmental” view that Ruscha represented. Critics like Peter Plagans and Kenneth Frampton saw that view as aloof from the life that people lived in these places, or as resigned to the unfolding of capitalism without criticizing it. Scott Brown, in contrast, saw Ruscha’s view as an antidote to the kind of top-down alienation characteristic of urban renewal.

None of those writers could have known that Ruscha would stage this project over time, but this unfolding offers a new way of thinking about the politics of his photographic project. He was building an archive (“I just put them in a lab and salt them away,” he told another interviewer in 1999) that future researchers could use to tell precisely the kinds of stories of urban change and ground-up transformation that reveal the social, economic, political, and cultural dynamics of the late twentieth-century city. We don’t think Ruscha is forcing one view of the city on those researchers, but rather encouraging them to do the work of puzzling out what changed and, most importantly, who did it and why. That ambition is not deadpan at all; it’s both active and proactive in a way that really helped us to see Ruscha as an extraordinary urban documentarian as much as an artist.

What subjects and histories are future essays engaging in SOS?

In addition to the stories already published on the website, forthcoming essays focus on gas stations, palm trees, banks, ethnic restaurants, movie marquees, Latinx businesses, and fonts and signage. Through these, we have made a start on a number of research questions that the project opens up. Still, there are myriad research questions that remain unanswered, and for which we hope our work can provide a foundation and an example. A small sampling includes questions about real estate speculation, housing and retail gentrification, building maintenance, the changing landscape of shopping in the United States, and even driving habits, all of which appear in Ruscha’s photos. In addition, we have only touched on the variety of architectural and urban typologies that these images depict, each of which offers its own avenues for further research. Bus stops and phone booths, hotels and motels, single-family houses (an exception on these primarily commercial miles of Sunset Boulevard), and coffee shops all offer lenses onto much bigger themes about how people have used, transformed, consumed, and redeveloped American cities. Our main ambition in creating this site has been for it to serve as a spark or tool for future research. Thus, we hope that other researchers might take up the above themes, and many others, either in independent scholarship or in further narrative essays that we can host on Sunset Over Sunset’s Stories page.

Did working on SOS confirm your prior beliefs about Los Angeles history, challenge them? Some combination of both?

While we recognize that the photographs and their geography are particular to Los Angeles, we found in this project a way to rethink the postwar American city–-and our assumptions about the way it has changed across the past half century–-more broadly. The classic story of urban change in this period has focused on the impact of large-scale projects and plans, publicly funded in the immediate post-World War II period, and more recently, the product of public-private partnerships. In LA, this includes projects like the urban renewal of Bunker Hill, the construction of Dodger Stadium, and, more recently, the Staples Center. While such large-scale changes to the urban fabric have been important, their top-down nature, the prominence of the personalities that drove them, and the comprehensiveness of their documentation in archives have served to overstate the degree to which massive actions were the driving force of cities between the 1960s and early 2000s. More ubiquitous were the myriad small gestures that remade the urban fabric through relatively modest demolition, construction, addition, and rehabilitation at the property level. We call this “vernacular redevelopment.” Think, for example, of facade changes, two lots giving way to a single building, or even repainting or a new sign, all of which have largely escaped archival documentation. Such incremental moves don’t really exist in public reports, mayoral papers, or even building records.

As historians interested in those small moves, we were struck by the rarity of Ruscha’s documentation, as, among other things, a careful accounting of how individual properties changed over relatively short intervals of time. Across time and space, such small but common changes added up to be consequential. Shifting our focus to vernacular redevelopment brings so many other kinds of actors–-small-scale entrepreneurs and restaurateurs, landlords and tenants, signmakers and gardeners–-into the story of urban change in LA and its urban counterparts too.

What proved to be the biggest obstacle in the construction of the project?

The biggest obstacle to the project was the technical dimension; specifically, finding a partner with the skills and interest to design and develop the website we envisioned. In many ways, there is a disconnect between the intensive process of design, development, and iteration required in digital humanities projects and the economic environment in which such projects take place. Digital humanities-related developers claim skills that reap far greater financial rewards outside of academia. Even with the critical support of an NEH grant, our budget was limited.

Creating a custom web project like Sunset Over Sunset requires technical expertise that humanists like ourselves are unlikely to have. We were challenged to simply articulate our technical needs in a way that would be legible to developers, to identify potential developers to whom we should reach out, and to evaluate the suitability of various potential partners once identified. To the extent that universities and their digital humanities centers can help bridge that divide, they would be filling a significant gap between project vision and implementation. We were so fortunate to have been able to partner with Rob Nelson, who brought to bear his unique expertise in the urban digital humanities, ultimately making the finished project possible.

How do you envision audiences will interact with the project? What are your goals for it ultimately?

We envision this to be a fun and informative project that will at once engage scholars, professionals, and the public. In particular, we expect the resources on Sunset Over Sunset to be of interest to scholars in multiple disciplines who study cities and their representations, including urban and architectural historians, designers, planners, and historic preservationists. We also hope to attract a wider audience of non-specialists interested in the history of cities, United States social and cultural history, and the history of Los Angeles in particular. We hope that all of these groups will find uses for Sunset Over Sunset as an exploratory and research tool and that such explorations may lead to additional insights and even scholarship. If the site is meeting this goal, then curious visitors will spend twenty minutes “walking” along Sunset Boulevard, discovering the quirky insights close looking enables, and reading the narratives on the site. And, at the same time, scholars will return again and again to the site’s photos and embedded data to pursue the kinds of longer-term research projects that this interface puts within reach.

Where does this project fit into the larger universe of the digital humanities?

The thriving field of spatially and visually oriented digital humanities work inspired our own efforts. These projects often join historical data sets in a single digital portal, make archives more accessible to scholars and the public, and at times help site visitors interpret these urban histories. For example, although not exclusively urban, Photogrammar innovatively maps another massive photographic collection–-the Farm Security Administration collection at the Library of Congress–-across space, time, photographer, and thematic content. 1940s.nyc and 80s.nyc both look closely at one particular city, New York, to map the tax photographs housed in its Municipal Archives. In the now-defunct Invincible Cities, Camilo Vergara used his own camera to rephotograph and map change in four U.S. cities. Mapping Inequality and Renewing Inequality make government documents–-including redlining maps and urban renewal displacement reports-–visually expressive, user interactive, and easily interpretable. The topic of urban renewal has developed its own DH subfield. For example, Preserving Society Hill joins photographs, urban renewal data, and oral histories to document the postwar history of a Philadelphia neighborhood; Picturing Urban Renewal builds upon 98 Acres in Albany to interpret the physical and social stories of urban renewal in four cities in New York State; and Bunker Hill Refrain uses survey data to reconstruct the history of a Los Angeles neighborhood that urban renewal destroyed.

In bringing together photographs, non-visual data, and interpretation, we’ve positioned Sunset Over Sunset as both an extension and synthesis of the digital urban history approaches mentioned above. Neither archive nor map, the two most common approaches for digital humanities projects, the site stands somewhere in between. It thus offers an important point of view on urban change in Los Angeles–-and other cities-–that highlights the gradual work of individuals over the kinds of big projects that have tended to attract the most attention from scholars and observers. If we had to make one argumentative claim about the site’s revelations, it would be that huge, world-changing phenomena like immigration, climate change, and globalization played out in surprisingly subtle, gradual ways on the ground. It’s hard to see stasis, small-scale change, and the work of individual hands through other means, but examining expansive stretches of one roadway across multiple decades of time through digital technology enables us to tell that story in a way that focusing on maps, more limited photographic surveys, and even textual documents alone do not.

More broadly, we hope the project will inspire others to consider the potential for digital humanities tools not only to archive and spatialize existing data sets, but also to layer such data sets and to extend their application from representation alone to interpretation as well.

The Sunset Over Sunset directors are Francesca Russello Ammon, Brian Goldstein, and Garrett Dash Nelson. Ammon is associate professor of City & Regional Planning and Historic Preservation at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design. Goldstein is associate professor of Art History at Swarthmore College. Nelson is president of the Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library.

Featured image: Panorama view, Sunset Over Sunset, https://www.sunsetoversunset.org/.

.