By J. Mark Souther

Few things embody the freedom of American life more than mobility, and perhaps no other form of transportation, for better and worse, has defined mobility in the United States like cars. Yet in the era of Jim Crow, mobility for Black families could be dangerous, even deadly; hence the need for The Negro Motorist Green Book, known colloquially as the Green Book, which provided Black motorists and their companions with restaurants, hotels, and other sites where race would be no issue, giving them the ability to navigate the nation by its roads and highways without or perhaps with minimal forms of discrimination. Cleveland State University historian J. Mark Souther and his students established Green Book Cleveland over a decade ago in an attempt to map The Green Book’s presence in and influence on Ohio. We sat down with Souther to discuss the project.

When and how did Green Book Cleveland (GBC) come into being and what role did you play in its development?

Green Book Cleveland (GBC) emerged from two strands of activity in the 2010s. First, it grew from my interest in curating Cleveland locations that appeared in the Green Book, a guidebook published annually from 1936 to 1966 to help African American travelers find safe, welcoming services from hotels to restaurants to beauty and barber shops and more. Starting in 1938, those guides expanded their coverage from New York City and became nationwide. In 2013, one of my graduate students researched a digital essay about the Majestic Hotel, which was the largest Black-owned hotel between New York and Chicago, for another digital project, Cleveland Historical. Cleveland Historical was our first use of the CSU-developed, Omeka-based Curatescape platform. My student found that the hotel was listed in the Green Book, which is when I first learned of the Green Book. An initial survey of available archival materials turned up little, which led me to file this idea away for the time being.

The second backstory to GBC was similarly generative. At that time, in addition to continuing to develop Cleveland Historical, I was also working with my CSU colleagues Meshack Owino and Erin Bell on a pair of NEH digital humanities grants (in 2014-15 and 2017-18). Each grant involved researching and developing a mobile-first web-publishing framework optimized to address technological and financial hurdles to adopting place-based digital narrative projects in the developing world. Specifically, we sought to emulate Curatescape by creating a plugin to extend the functionality of WordPress to support geolocated stories and tours. We partnered with Maseno University in Maseno, Kenya, and initiated a several-year research collaboration in which CSU and Maseno students worked together to curate place-based digital stories and tours of Kisumu, Kenya. The outcomes of the grant included the MaCleKi website, which we built in WordPress using the grant-funded Curatescape for WordPress plugin that we created especially for developing-world contexts. When WordPress introduced its new block editor in 2018, we decided to rethink the plugin in a way that would make it lean into the emerging WordPress setting and offer maximum flexibility for project development. In 2020 we obtained another NEH grant that supported our development of the PlacePress plugin, which is the tool we used to create GBC. PlacePress adds special Location and Tour post types, as well as a Global Map block to WordPress.

In summer 2021, I conceived Green Book Cleveland as a place-based mapping project that I would develop first with students in my public history course, which we started doing that fall. Initially, I expected to document histories of the approximately sixty Cleveland businesses that were listed in the Green Book over the years. I soon decided to go beyond the Green Book itself, partly because I like to work on projects that can remain active over a period of at least several years. Sixty locations seemed too restrictive. In addition, after teaching graduate seminars on suburban history and urban environmental history, I had become increasingly interested in how African Americans in cities sought suburban and rural recreation. As a result, I decided the Green Book could provide the core thematic frame for a project that would encompass Black leisure, recreation, and entertainment throughout Northeast Ohio in the era of the Green Book, not just places listed in the guides. This approach meant that we could uncover histories of beaches, lakes, resorts, amusement parks, picnic groves, and other places that the Green Book never included.

As noted in the site’s introduction, a number of partners and organizations have contributed to its growth. How did you go about incorporating outside stakeholders?

One of the students who was in my public history class had worked on historic sites of Black recreation as a summer intern at Cuyahoga Valley National Park, and he shared the news of the emerging Green Book Cleveland project with one of my longtime colleagues there. She was immediately interested and suggested that we meet to discuss shared interests. We talked about the GBC concept on a morning hike in the one of the Cleveland Metroparks reservations, and that led to a partnership because of our overlapping interest in African American access to green space.

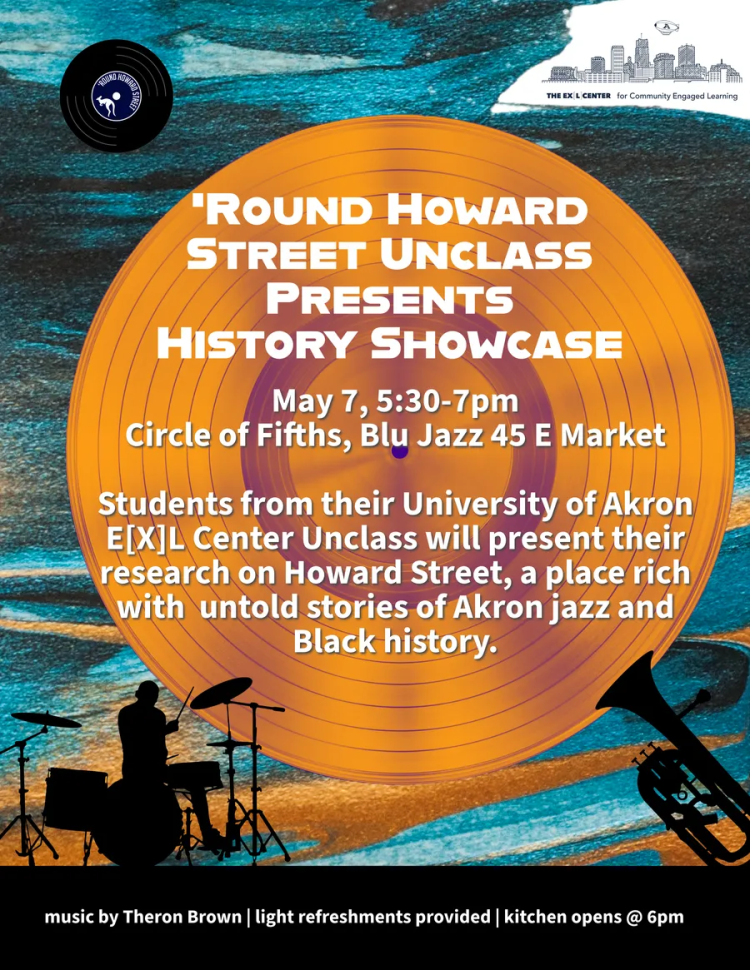

In February 2022, following extensive media coverage of Green Book Cleveland’s initial release, we convened a meeting that pulled together many of those who had expressed interest in the project. From there, those most interested in shaping the project’s evolution into a broader, publicly engaged collaboration formed a steering committee. The committee reflects institutional and organizational interest in using this history to inform contemporary planning for inclusive park spaces, but it also dovetails with the grassroots community engagement of ThirdSpace Action Lab, an organization based in Cleveland’s historic Black neighborhood of Glenville. Our regional project and ThirdSpace’s more neighborhood-based Chocolate City Cleveland digital project became mutually supportive, and we’re in the process of incorporating an oral history component to support both of our projects. The student research component of the project also expanded this past year to the University of Akron, where Dr. Gregory Wilson’s public history seminar and Dr. Hillary Nunn’s “‘Round Howard Street” [un]class curated content on some of Akron’s Black leisure sites. In short, it’s been heartening to see how resonant the project has been for so many people.

What themes emerged as GBC came together and how did you work them into the site?

Well before we developed the website, the concept had expanded beyond Green Book listings in Cleveland. The more expansive approach necessitated considering how best to convey the project’s focus through design choices. Even the project’s name was tricky. We decided to call it Green Book Cleveland because of its initial scope even though it came to encompass Akron, Canton, Youngstown, Lorain, and smaller communities like Oberlin. The subtitle, “Black Leisure, Recreation, and Entertainment in Northeast Ohio,” helps users see the metropolitan and regional focus. Moreover, the choice to use a 1940s photo of campers at the Phillis Wheatley Association’s Camp Mueller in the Cuyahoga Valley on the homepage draws further attention to outdoor recreation as an important theme.

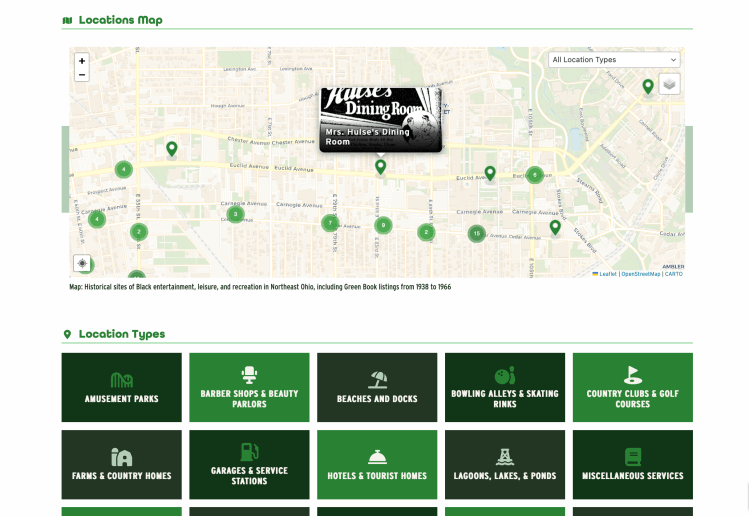

We also made other choices to reinforce the broader focus while preserving some of the original Green Book basis. For one, we adapted the categories used in the Green Book to create a broader range of “location types.” Second, each location that was in the Green Book has a “Green Book Details” section that indicates which editions listed it, all addresses it occupied, and any anomalies (the Green Book sometimes erroneously named or located listings, so this enables us to account for discrepancies). Third, users can click on tags to see which locations appeared in any edition of the Green Book. Finally, users can filter the project’s global map by location types as well as to view only those locations that were listed in the Green Book.

What proved to be the biggest obstacle in the construction of the project?

No one obstacle that stands out, but I can immediately think of several challenges, some of which are features that would be nice to have but either don’t fit with the way PlacePress works or risk adding too much complexity. Since we are in part electing for GBC to showcase how the plugin works, we’re hesitant to add features that might obscure its essential functionality.

For example, it would be great if the map could be connected to a timeline to show the lifespan of specific locations, or if we could map tags to see only Green Book-listed locations in, say, 1946. I could also imagine further filtering that would point users to those places that were Black-owned, places that African Americans used but only within the constraints posed by exclusionary or segregationist policies or threats of racial violence.

Another challenge is that our approach doesn’t call immediate attention to some of the interesting insights that a close, comprehensive reading of the site’s content can reveal: e.g., the interesting networks of association among entrepreneurs, workers, or performers across locations, the presence of Black-owned or Black-patronized venues in times and/or places that recast what we thought we knew, and the class differentiation of patronage across various geographies.

It probably goes without saying, but archival and newspaper sources of information on these places often leave uncomfortable gaps and silences. Oral histories may fill some of these, and readers’ choice to share their stories using the form at the end of each location narrative can fill others, but the problem isn’t one that we can completely overcome.

How did working on the project influence or shape your view of this history, whether it be the role of the Green Book in Ohio, Cleveland’s place in it, or any other aspect of the project? Did it confirm your prior understanding? Did it reveal new unexpected insights? Some mix of both?

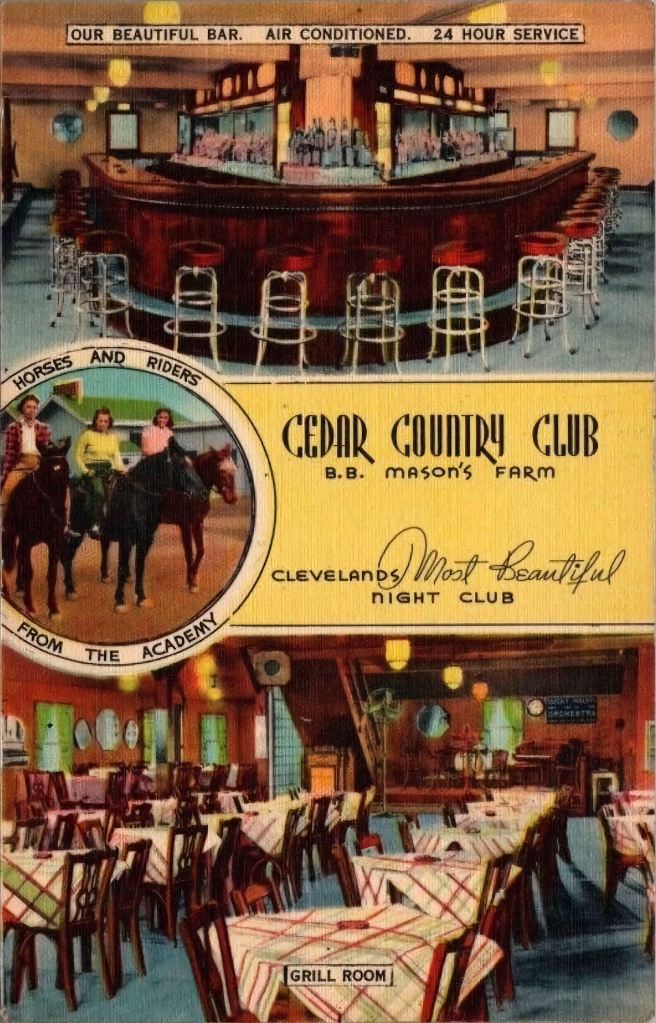

When we decided to go beyond the Green Book listings alone, we opened up the opportunity to recast what we thought about Black history in Cleveland. So often our attention has been on key central-city neighborhoods — Harlem in New York, the Black Belt in Chicago, Bronzeville in Milwaukee, Paradise Valley in Detroit, Hill District in Pittsburgh, and Cedar-Central in Cleveland — and on the process of racial transition in outer neighborhoods and, ultimately, Black suburbanization. Historians have certainly pointed to subjects like suburbanization as having longer, more complex histories than a simplified tale of decentralization, but we found ourselves becoming more attuned to a longstanding Black presence, albeit often one that was ephemeral, in outlying rural areas on the periphery of Cleveland well before they developed as largely White suburbs and before some of them eventually became integrated suburbs. We learned about Black entrepreneurs who created lakefront beach communities like On-Erie Beach and Burton’s Bathing Beach, roadside music clubs like Lake Glen on the highways beyond the suburbs, and recreational resorts like Mason’s Farm in the wooded hills of the Cuyahoga and Chagrin river valleys.

In the city itself there were additional surprises. I was shocked that no one had ever commented on the fact that Cleveland’s famed Agora Theater, widely known one of the principal venues that gave the city its reputation as a proving ground for emerging rock ’n’ roll acts in the 1970s, had previously served as a popular Black venue for popular music and other forms of entertainment during World War II, and this at a time when Euclid Avenue was decidedly on the white side of the city’s east-side color line. I was also intrigued to find what appears to be the first Black-owned retail business on Euclid Avenue. Mrs. Hulse’s Dining Room opened by Birmingham, Alabama native Carrie Hulse in 1948, fully two decades before Winston Willis’s iconic Black entertainment empire emerged on the street.

Ironically, most of the surprises came not from studying the actual Green Book sites, but rather from the decision to look more holistically at the landscape of Black leisure, recreation, and entertainment at the metropolitan and even regional scale in the Jim Crow era. Doing so also enabled us to present a more balanced picture of Black leisure, recreation, and entertainment that provided not only great stories of business success and family and community joy but also the struggles — exclusionary zoning, eminent domain, law enforcement raids, arson, and assault — that often confronted Blacks pursuing these activities outside the bounds of their own redlined neighborhoods. Needless to say, I’m thankful for the turn the project took to be more encompassing.

How do you envision audiences will interact with the project? What are your goals for it ultimately?

The response to GBC has been incredible. From the moment the project went live in 2022, we’ve been fortunate to have considerable media coverage, including front-page articles in both the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Akron Beacon Journal, appearances on the local NPR radio station, and more. An initial flood of calls and emails has settled into a slower but still steady flow of inquiries and conversations. To date, most interaction has been through public engagement with the website itself. In the past year alone, the website garnered 40,000 page views, and users have written more than seventy comments on the site’s location narratives. The project team has met regularly with community-based organizations to explore how GBC can inspire, inform, and support initiatives that others are pursuing. And entities ranging from the Cleveland Metroparks to the Cleveland City Planning Commission have been using the project in their own place-based planning work. In the future, visitors to our area’s national park and regional parks will find insights from this project suffusing public-facing interpretation. Ultimately, I also envision GBC leading to more intentional interventions that might result in communities reclaiming stories and even physical spaces.

Where does this project fit into the larger universe (galaxy?) of the digital humanities?

GBC is very much attuned to the idea of leveraging the digital humanities to create shared spaces for inclusive, affirmative public dialogues about the interconnections between place and history and between past and present. It’s also squarely within one constellation in that DH galaxy: place-based storytelling.

Where do you see digital humanities going in the future? How does GBC relate to this trajectory?

The rapid, dizzying advances we’re seeing in AI sometimes appear to be flinging us more quickly into a future in which the humanities are imagined either as imperiled or destined for radical transformation. Immersive experiences made possible by continuing advances in extended reality (XR) provide perhaps a clearer sense of where DH is moving, and I fully expect the various forms of XR to continue to press and entice us to do some of what now feels out of reach without huge budgets. I see a bright future for place-based storytelling that incorporates advancing technological affordances. I’m not sure what it means for GBC and my center’s other digital humanities endeavors. On some level, I think there will continue to be strong demand for interactive projects that perhaps link out to related immersive ones without always necessarily going “all in” for creating new immersive “worlds.” If all of this suggests that I don’t have a very clear window into the future, let me end with my faith in the idea that regardless of the user experience, DH will continue to require the same types of work we are doing right now — framing projects with sound scholarship, mining primary sources, making decisions about structuring and presenting knowledge, seeking ways to share authority and invite dialogue, and anchoring our work in archival standards that ensure the durability and transferability of projects’ building blocks and content.

Mark Souther is a Professor of History and Director of the Center for Public History + Digital Humanities at Cleveland State University, where he teaches courses on urban and public history and guides development of digital history projects and DH tools. He has published books on Cleveland and New Orleans as well as articles in the Journal of Urban History and Journal of Planning History, among others.

Featured image (at top): A photo of the Phillis Wheatley Association’s Camp Mueller in the Cuyahoga Valley is the featured image on Green Book Cleveland. Source: National Park Service.