Sharon D. Wright Austin, ed. Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023.

Reviewed by Sarena Martinez

Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by political scientist professor Sharon D. Wright Austin, is a trailblazing volume that draws together twenty-two contributing authors to assert several conclusions. Black female mayors face considerable challenges in campaigning and governing because of their race and gender. By and large, their focus is on economic equity, education, and community empowerment. And Black female mayors are formidable political actors, especially when “more of them are running for office—and winning—each year.”[1] Still, the book falls short of helping the reader understand how to harmonize the various viewpoints of the authors.

Today, the “local” is at the forefront of the toughest challenges facing our country: climate change, gun violence, poverty, housing, demographic change, and more. Expectations of what a city should do are implicitly built upon a foundational understanding of what a city can do, informed by historical and contemporary interpretations of what it has or perhaps hasn’t done—a narrative that has largely excluded Black female mayors until now. This volume is a crucial addition to the discourse on urban governance and the intersection of race, gender, and power in American politics. And excitingly, Austin reveals in the conclusion that a second volume is already in the making, which will expand the study to more Black female mayors, and consider sexual orientation and multiracial identities.

This book draws from newspaper reportage, interviews, and X (formerly Twitter) data to examine “the acquisition of power (their campaigns) and the actual exercise of power (their governance)” of twenty-three Black female mayors from the 1970s to the present.[2] The book’s animating questions are tactical—How did mayors win? After they win, what are their governing priorities? What challenges do they encounter, and from whom? And they are a welcome departure from the tired, late-twentieth-century question of whether or not Black (usually male) mayors were successful. Instead, the authors are interested in searching for agency within each mayor’s campaign strategies and contributions to her city.

Political scientist Andrea Benjamin, for example, argues that in 2017, Mayor Vi Lyles of Charlotte (in office from 2017 to present) followed some of “the rules: She built a decent coalition, and she stuck to women’s issues,” but she also strategically centered race in her campaign, speaking “explicitly about the challenges facing Black citizens in Charlotte, and she won.”[3] Lyles ran in the wake of the city-state battle over an ordinance passed by the Charlotte City Council in 2016 that allowed transgender people to use the bathroom of their own choosing, which triggered a state bill (HB2) requiring North Carolinians to use bathrooms that corresponded to their birth certificate-assigned sex; and widespread protests over the killing of Keith Lamont Scott, by a Black police officer.[4]

Chapter 6 explores two Mississippi Delta mayors—Mayor Unita Blackwell of Mayersville (1976-2001) and Mayor Sheriel F. Perkins of Greenwood (2006-2009). “It can be argued that Blackwell literally created Mayersville,” note scholars Emmitt Y. Riley III, Minion K. C. Morrison, and Yolanda Jones, resisting “the almost one hundred-year lack of the franchise for African Americans.”[5] In her first years in office, facing the “absence of indigenous local sources of wealth for investment, and facing an often-hostile state legislature,” she turned to her “vast network of external nongovernmental and federal government allies” to bring resources for infrastructure, and welfare services to Mayersville.[6] In 2006, the authors chronicle how Mayor Perkins had to issue a challenge in court and win a legal battle before she was able to ascend to her elected office. “Despite the process of countermobilization,” she pursued a very “aggressive agenda” focused on alleviating poverty and crime, and improving education and infrastructure.[7] She invested in sidewalks and street repair, securing over $661,000 in grants. She instituted the first Mayor’s Youth Council to involve young people in governance, appointed quality school board members, and worked with the school system to improve infrastructure.

The authors remind us that “disgraced” mayors contributed to their cities as well. In offering a candid assessment of Mayor Lovely Warren of Rochester (2014-2021), who resigned “from office in disgrace,” Angela K. Lewis-Maddox and Stephanie A. Pink-Harper conclude that “Warren advocated economic growth strategies that benefited citizens from all socio-economic backgrounds during her mayoral tenure.”[8]

The volume’s title, “Political Black Girl Magic,” reflects Austin’s respect for the Black female mayors under study. Refreshingly, this esteem is espoused throughout the volume. For example, political scientists Precious Hall and Austin reflect on Mayor Aja Brown of Compton’s (2013-2021) commitment to service: “In speaking with Mayor Brown, one thing was clear: she has a heart for her family and a heart for her community…One thing that can’t be denied is that she did a lot for the city of Compton during her time in office.”[9]

Historian Ashley Robertson Preston and political scientists LaRaven Temoney and Kelly Briana Richardson reflect on Mayor Hazelle Rogers of Lauderdale Lakes (2016-2022), Mayor Yvonne Scarlet Golden of Daytona Beach (2003-2006), and Mayor Barbara Sharief of Broward County (2013-2014, 2016-2017), observing that “although it is difficult to serve as the mayor of an American city, these women have done so with candor, diligence, and grace.”[10]

Political scientists Fatemeh Shafiei and Austin conclude that the real legacies of Atlanta mayors Shirley Franklin (2002-2010) and Keisha Lance Bottoms (2018-2022) “remain in the multitude of significant policy imprints, programs, and institutional reforms that continued to benefit the city, the region, the nation, and the world after both left office.”[11]

Running a city, after all, is hard work. And as the authors show, it is even harder work for Black female mayors. In chronicling the administrations of Washington D.C. mayors Muriel Bowser (2015-present) and Mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly (1991-1995), political scientist Linda Trautman concludes that “the effects of gender discrimination and racial bias experienced by Pratt Kelly were pervasive and ingrained within the municipal governance, such as the city council and among constituents.”[12]

Austin devotes an entire section of the conclusion to recounting the standoffs between former President Trump and Black female mayors. He called Mayor Bowser “incompetent,” and authored a letter to Mayor Lori Lightfoot of Chicago (2019-2023) and Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker attributing the “continued violence in this Great American city” to Lightfoot’s lack of commitment to her constituents. Lightfoot’s response accused Trump of “attacking and trying to undermine every big city Democratic mayor, especially the woman.”[13]

Implicit in the question of how a mayor governs is to what extent a mayor can govern, a question beset with semantic, conceptual, and historical difficulties Throughout the thirteen chapters, the authors weave rich narratives that dive into the realpolitik of urban campaigning and governance, underscoring one of the volume’s most important methodological contributions: the contemporaneous study of governance. Rather than focusing on one particular policy, the charge of the authors is to draw conclusions about the process by considering them simultaneously and together. Authors have to wrestle with what it means that the mayors are dealing with developing their cities’ economies while combating homelessness, managing COVID-19, and dealing with their state legislatures.

Dealing with this complexity is no easy feat, and the authors should be commended for the approach. However, as a reader, it is difficult to understand how to synthesize the various author perspectives. In the upcoming second volume, a more explicit connection of the dots would enhance the portability of contributions into fields such as history, political science, and urban studies.

For example, beyond a discussion of the various legal arrangements that structure city and council governance (e.g., strong mayor/weak council), we are still left unsure of what Austin means by power when she says that the goal is to study “the acquisition of power (their campaigns) and the actual exercise of power (their governance).”[14] Several authors draw from Clarence Stone’s regime politics, but it’s hard to understand how Austin—or the various authors—understand how “power” or the “regime” changes over time, if at all.

Over the last decade, for example, state governments have increasingly used state laws to nullify local ones, a proliferation of preemption characterized by legal scholar Richard Schragger as an “attack on cities.” States have voided minimum wage laws, punished cities for adopting gun control measures, and forced municipalities to maintain Confederate monuments.[15] The Charlotte bathroom bill is a key example, but what are the takeaways for how this erosion of local power affects how Black female mayors govern?

The biggest lesson that these officials have proven, Austin argues, is best summed up by the former mayor of East Point, Georgia, Patsy Jo Hillard: “[Y]ou have to work together.”[16] Do Austin and the other contributing authors mean to suggest that this interdependence and collaboration is a source of power to advance the mayor’s agendas? Undoubtedly, legal scholar Heather Gerken would encourage them to say “yes”! Gerken argues that localities derive power not from independence but from interdependence. States, for example, rely on cities, which means local officials can “edit the law” they are relied on to administer. They can also use their insider status to serve as “connected critics,” standing a “little to the side, but not outside” of the community they challenge.[17]

Relatedly, how does having to collaborate impact the agency of Black female mayors? How should we understand the intersection of class with the need to collaborate? We are told that most Black female mayors have Bachelor’s degrees and class arises in the context of analyzing the personal dilemmas of individual actors. And various chapters refer to the mayors being perceived as “elites.” But how should readers understand the broader intersection of class with race and gender when it comes to campaign and governance?

The source of the chapters’ richness, newspaper articles, also needs more explicit critical interrogation. The media’s construction of narratives of Black female mayors’ campaigns and governance likely affects their credibility and ability to govern. But readers are left unsure about how to understand the interplay between broader media and Black female mayors’ campaigns and governance. And how to understand the difference (if any) from coverage of Black male mayors.

This question is important because, as historian George Derek Musgrove has argued, the story of conservative backlash to Black (male) elected officials through the white-dominated media’s harassment of them between 1965 and 1992 explains much of our political warfare today.[18] How would contributing authors understand or reflect on the dynamic of Black female mayors and the media three decades later? Just as important a question is what the media is not chronicling. As Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) reminded us in a 1992 special edition of the groundbreaking Black Power, “just because the capitalist press does not record history does not mean history is not being made.”[19]

Overall, this book is a testament to the resilience, dedication, and power of Black female mayors. It sets the stage for crucial future research, not just with the questions it raises, but as a model for the potential of collaboration in scholarship. The volume itself is a testament to working together—five of the thirteen body chapters are co-authored. In sum, Political Black Girl Magic is an essential read for anyone interested in American political development, political science, urban studies, and social justice. And I, for one, will be eagerly awaiting Austin’s second installation.

Sarena Martinez is a History DPhil Candidate at the University of Oxford and an incoming Yale Law School student. Sarena’s dissertation is focused on the mechanics of urban power in Baltimore during the tenure of its first elected Black mayor, Kurt L. Schmoke. Previously, Sarena served as a Manager of Special Projects in the Department of Innovation and Economic Opportunity at the City of Birmingham, Alabama, where she managed a portfolio of projects supporting and building an inclusive economy. A Rhodes Scholar, Sarena earned her MSc in Economic and Social History from the University of Oxford. She holds a B.A. from Vanderbilt University in Psychology and an A.A. from Bard College at Simon’s Rock.

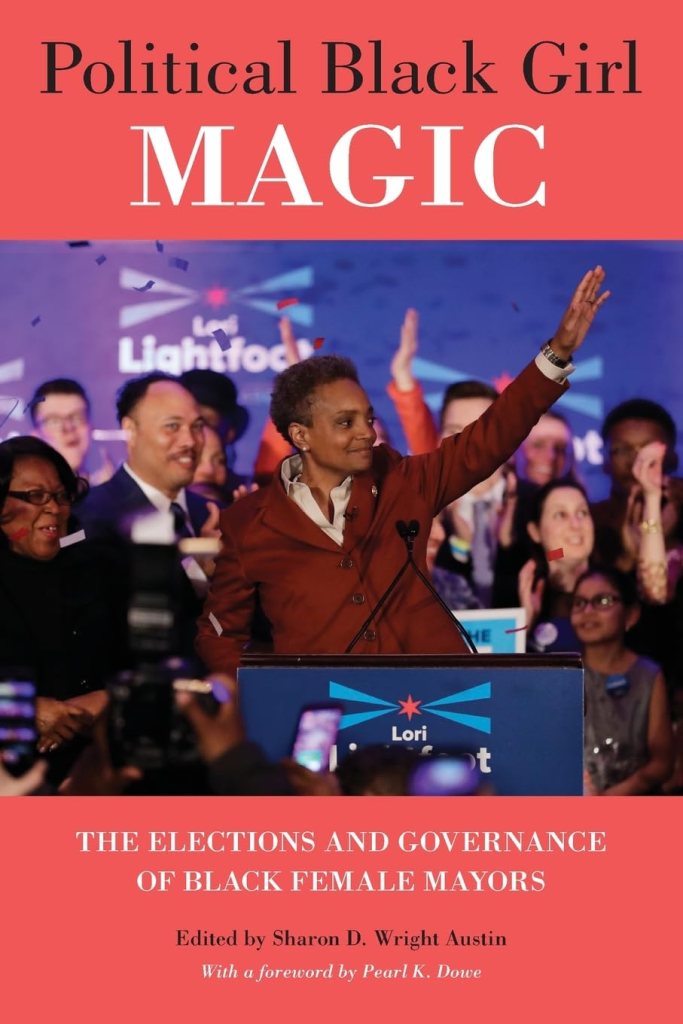

Featured image (at top): Lori Lightfoot, the first openly LGBT mayor of Chicago, marching in the 2019 Chicago Pride Parade. Lightfoot served as Grand Marshal of the parade. Photograph by Vashon Jordan Jr., 2019. CC BY-SA 4.0.

[1] Wright Austin, Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, 295.

[2] Wright Austin, 4.

[3] Benjamin, “A Woman Whose Father Didn’t Graduate from High School Can Become This City’s First Female African American Mayor: Mayor Vi Lyles of Charlotte,” 154.

[4]Benjamin, 154.

[5] Riley III, Emmitt Y., Minion K. C. Morrison, and Yolanda Jones. “There’s No Job Too Big to Benefit from a Small-Town Person’s Perspective: African American Female Mayors in the Mississippi Delta,” 122-123

[6] Riley III, Minion, and Jones, 123.

[7] Riley III, Minion, and Jones, 131.

[8] Pink-Harper, Stephanie A. “We Can’t Turn a Blind Eye to Change: Mayor Lovely Warren of Rochester,” 92.

[9]Hall, Precious, and Sharon D. Wright Austin. “Progress Comes at a Price: Aja Brown and Acquanetta Warren Govern California Cities,” 67.

[10] Preston, Ashley Robertson, Laraven Temoney, and Kelly Briana Richardson. “Others May Not Be Able to See What I See Now: Black Female Mayors in Florida,” 114.

[11]Shafiei, Fatemeh, and Sharon D. Wright Austin. “I’d Rather Go Down Fighting Than Stand as a Loser: Atlanta Mayors Shirley Franklin and Keisha Lance Bottoms,” 201.

[12]Trautman, Linda. “The Frustrations Have Been Festering for Twelve Years: Washington, DC, Mayors Sharon Pratt and Muriel Bowser,” 244-245.

[13] Wright Austin, 297–298.

[14] Wright Austin, 4.

[15] Schragger, “The Attack on American Cities.”

[16] Wright Austin, Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, 295.

[17] Gerken, “Federalism All the Way down.”

[18] Musgrove, Rumor, Repression, and Racial Politics: How the Harassment of Black Elected Officials Shaped Post-Civil Rights America.

[19] Carmichael, Ture, and Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America, 177.

Benjamin, Andrea. “A Woman Whose Father Didn’t Graduate from High School Can Become This City’s First Female African American Mayor: Mayor Vi Lyles of Charlotte.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 141–56. Temple University Press, 2023.

Carmichael, Stokely, Kwame Ture, and Charles V. Hamilton. Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. Vintage, 1992.

Gerken, Heather K. “Federalism All the Way down.” Harvard Law Review 124 (2010): 4.

Hall, Precious, and Sharon D. Wright Austin. “Progress Comes at a Price: Aja Brown and Acquanetta Warren Govern California Cities.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 56–79. Temple University Press, 2023.

Musgrove, George Derek. Rumor, Repression, and Racial Politics: How the Harassment of Black Elected Officials Shaped Post-Civil Rights America. University of Georgia Press, 2012.

Pink-Harper, Stephanie A. “We Can’t Turn a Blind Eye to Change: Mayor Lovely Warren of Rochester, New York.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 80–96. Temple University Press, 2023.

Preston, Ashley Robertson, Laraven Temoney, and Kelly Briana Richardson. “Others May Not Be Able to See What I See Now: Black Female Mayors in Florida.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 97–115. Temple University Press, 2023.

Riley III, Emmitt Y., Minion K. C. Morrison, and Yolanda Jones. “There’s No Job Too Big to Benefit from a Small-Town Person’s Perspective: African American Female Mayors in the Mississippi Delta.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 116–37. Temple University Press, 2023.

Schragger, Richard. “The Attack on American Cities.” University of Virginia School of Law, April 10, 2020.

Shafiei, Fatemeh, and Sharon D. Wright Austin. “I’d Rather Go Down Fighting Than Stand as a Loser: Atlanta Mayors Shirley Franklin and Keisha Lance Bottoms.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 183–207. Temple University Press, 2023.

Trautman, Linda. “The Frustrations Have Been Festering for Twelve Years: Washington, DC, Mayors Sharon Pratt and Muriel Bowser.” In Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors, edited by Sharon D. Wright Austin, 231–48. Temple University Press, 2023.

Wright Austin, Sharon D. Political Black Girl Magic: The Elections and Governance of Black Female Mayors. Temple University Press, 2023.

Most are very much unqualified taling heads that are easily controlled, will be corrupt very soon, hire all the family members to city positions and claim racism as a justifiable means to their inadequate qualifications. DEI has ruined the concept of the most qualified are elected……..very sad.

LikeLike