Editor’s note: This is the third entry in our theme for May, Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean.

by Alexandra Camille Schultz

Introduction: From Edge to Center[1]

In the early twentieth century, more people began to spend organized leisure time at the beach, including in Egypt. Indeed, by the end of World War II, the Mediterranean beach at Alexandria was central to the city’s identity. Especially for Cairenes (residents of Cairo) and regional tourists, Alexandria became synonymous with summer and beaches.[2] Women were key to the rise of Alexandria’s beaches and Egyptian beach culture. This essay explores the changes in landscape and popular culture that centered the beach and women—even as both occupied precious positions at the edge of the city and society, respectively.

I explore this claim with a selection of maps of Alexandria and its suburbs and a range of popular culture imagery from magazines, films, and songs, largely from the 1950s to early 1970s. The maps function in two ways. First, they are representations of the space as it was, or how it was perceived. Second, they are representations of state-driven attempts to order both of these things. There are countless textual and visual representations of the beach in Egyptian popular culture, especially in the postwar era. So much so that it forms a topos, a setting or device in which summer itself as a time, a place, and an experience is worked out. Beach topoi function as discursive cultural representations that informed and were informed by imagined geographies and everyday practice.

Changes in the Sand: Alexandria and its Beaches, 1800-1950

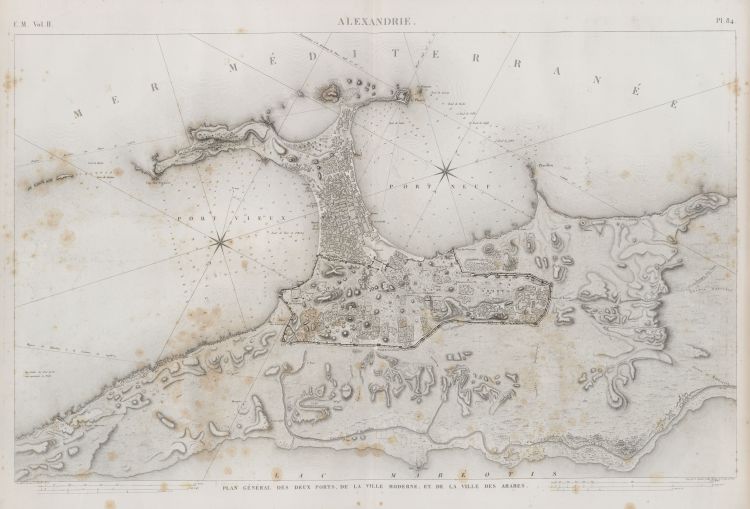

In 1801 Napoleon invaded Egypt, and accompanying researchers produced a detailed survey and map of Alexandria and its suburbs. The map represents a landscape of salt water and sand (featured image, at top).[3] Alexandria lacked a reliable freshwater source, which kept its population small. After summarily removing Napoleon and his army from Egypt, Muhammad Ali Pasha proclaimed himself governor and, among other things, ordered a large effort to re-dig and widen the Ashrafiya Canal, Alexandria’s link to the Nile. The project was completed in 1820 and provided city planners with the opportunity to push Alexandria’s sand to the edge.[4]

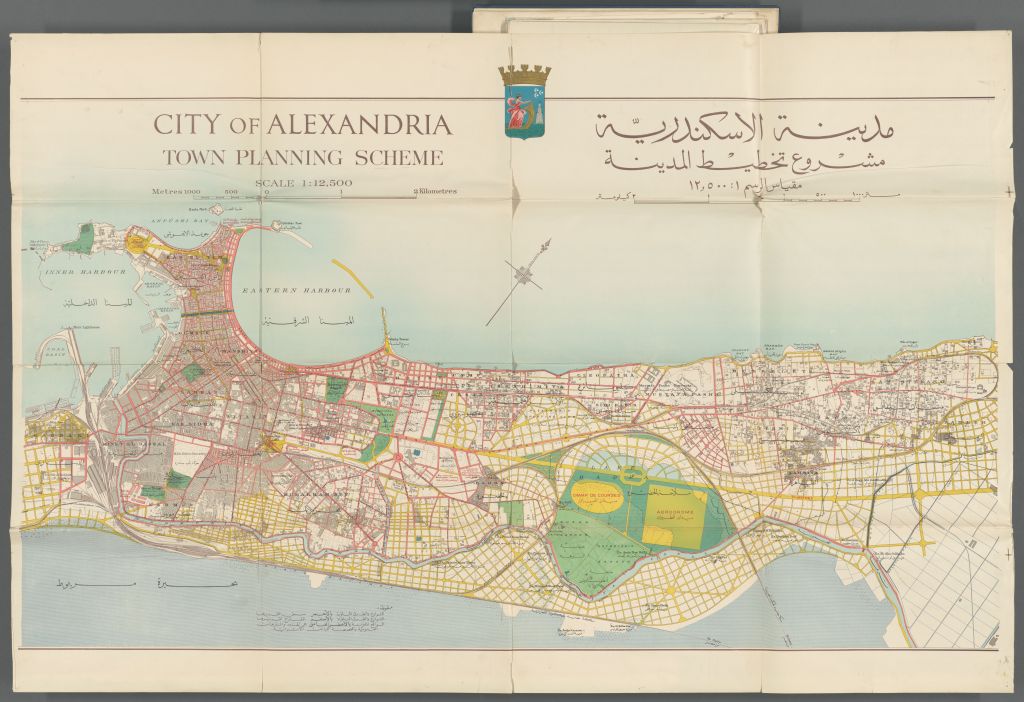

An 1865 map of Alexandria by polymath and local Alexandrine historian Mahmoud al-Falaki shows a dense city clustered on the peninsula and an irrigated agricultural landscape surrounding it (figure 1).[5] A 1921 plan completed by Alexandria’s chief municipal engineer, William McLean, indicates significant growth and the ambition of city officials to extend the city outwards (figure 2). The future of the city, according to this document, lay in the suburbs of Ramleh, along the shore to the east of Alexandria. Streets, rather than habitation, serve as the organizing feature of this expansion. Red lines indicate already approved road projects, and yellow lines indicate proposed improvements.[6] Egypt’s modern urban planners, such as Ali Mubarak and William McLean, favored this morphology, which combined a hierarchical ordering of streets, elements of radial and grid planning, as well as garden-city-style residential enclaves.[7]

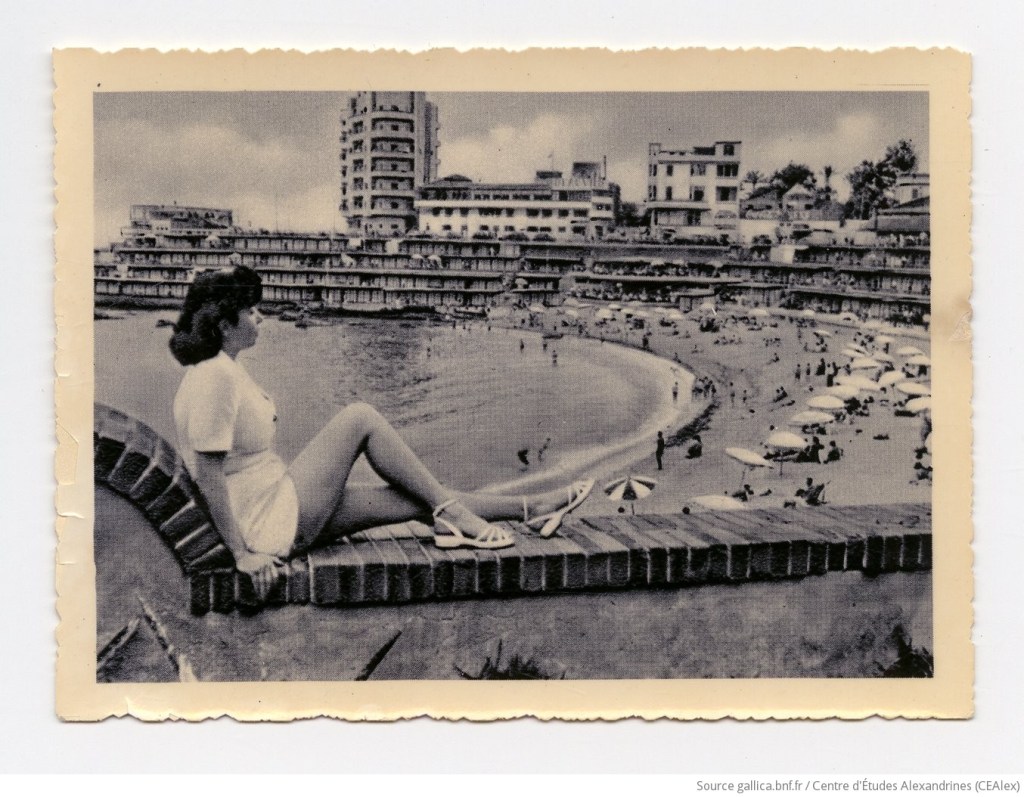

A map of Stanley Bay created in 1937 as part of the municipal atlas of Alexandria indicates the infrastructure and services available in these new spaces, including terracing, beach cabins for rent, public restrooms, a restaurant, and staircases for beach access from the street (figure 3). [8] Electric lighting, a nearby tramway stop, and the corniche road supported easy and comfortable access, while also encouraging people to make repeated lengthy visits. Often filled with beach umbrellas and many tiny bathers, photographs and postcards routinely feature Stanley Bay. A Lehnert and Landrock example includes a young woman in the foreground wearing shorts and stylish curls, looking out over the vista of the beach from a stone and brick parapet (figure 4).[9]

Going to the Beach

There is a long history of aquatic socializing in Egyptian cities, especially on Cairo’s seasonal lakes. By the late nineteenth century, photographic examples of large families gathering at the beach in Alexandria appear. At the same time, journals such as al-Muqtataf and al-Hilal published essays on the health benefits of sea bathing.[10] Articles on how to exercise properly, including how to swim, proliferated in the 1920s and 30s.[11] Women’s magazines such as Bint al-Nil, founded by Egyptian feminist Doriya Shafiq, included articles on the benefits of swimming for physical and mental health.[12] The atmosphere of the beach, in which people walked around minimally clothed in wide-open expanses of sand, brought these struggles to the fore. Women were fighting for autonomy in various political and everyday forms, the modernization of personal status laws, and the right to vote. Indeed, women’s bodies were the site of perennial conflict at the beach, from Ipanema to Alexandria to Nice.[13]

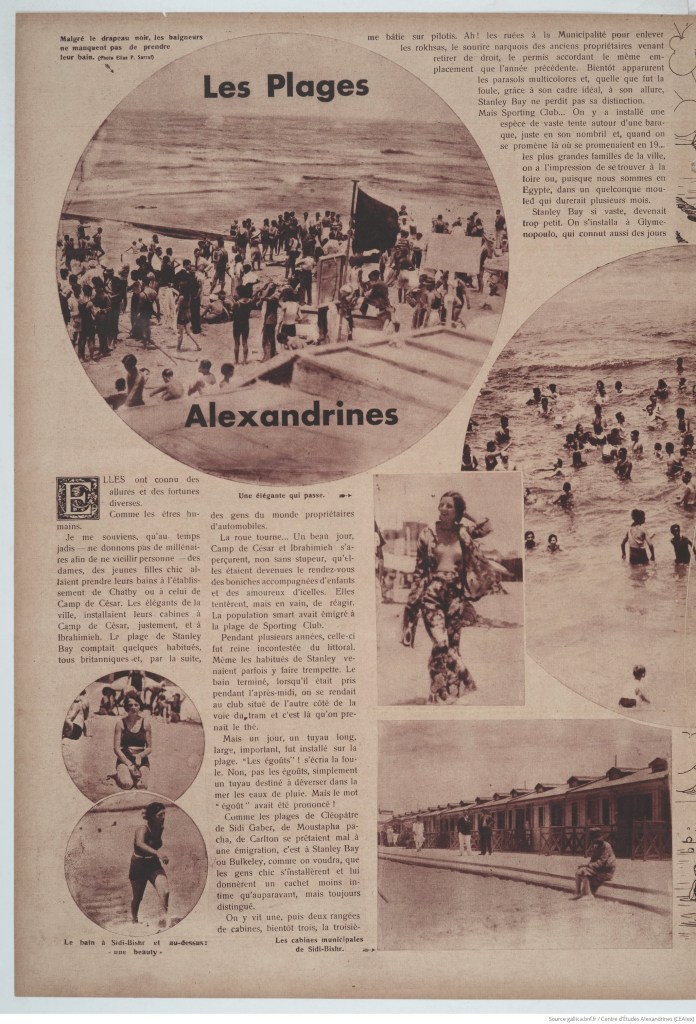

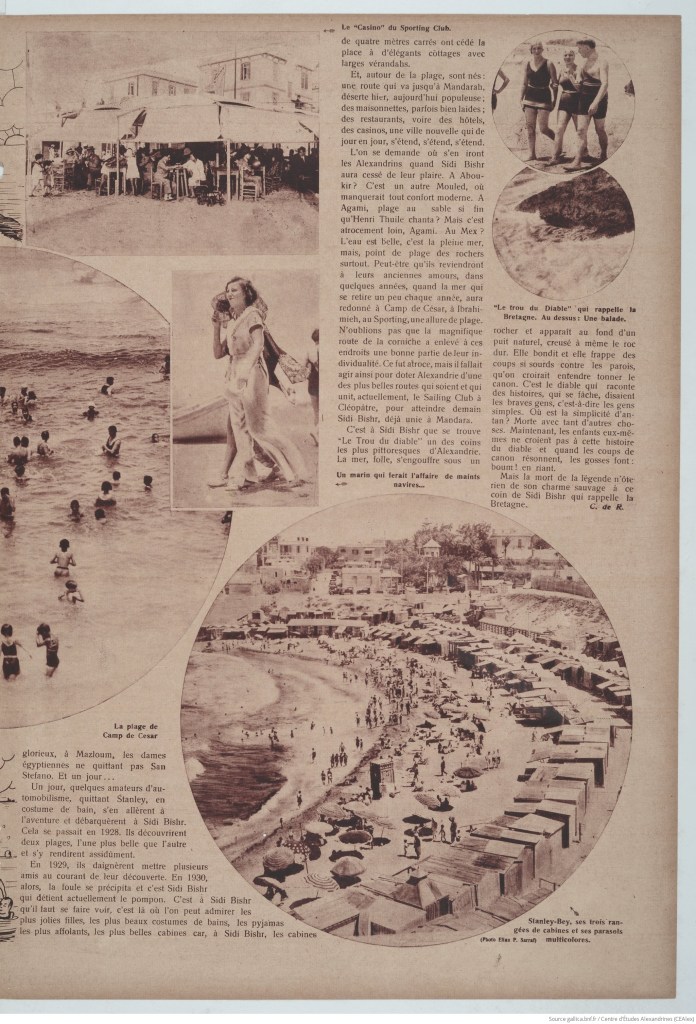

Early images of beach activity emphasize wealthy young people and the European, white, or white-presenting body.[14] The August 9, 1931, issue of Images, distributed by the Zaydan family publishing house Dar al-Hilal, focused on Egypt’s thriving beach culture (Figures 5-6).[15] Photographs exhibit playful and carefree groups in fashionable attire. Varied sizes and shapes, some cropped into roundels, compliment short quippish commentary. Captions often commented on women’s physical appearance, including their clothing and hair. The beach in these magazines is a place to be seen and to perform, document, and consume bourgeois identity.

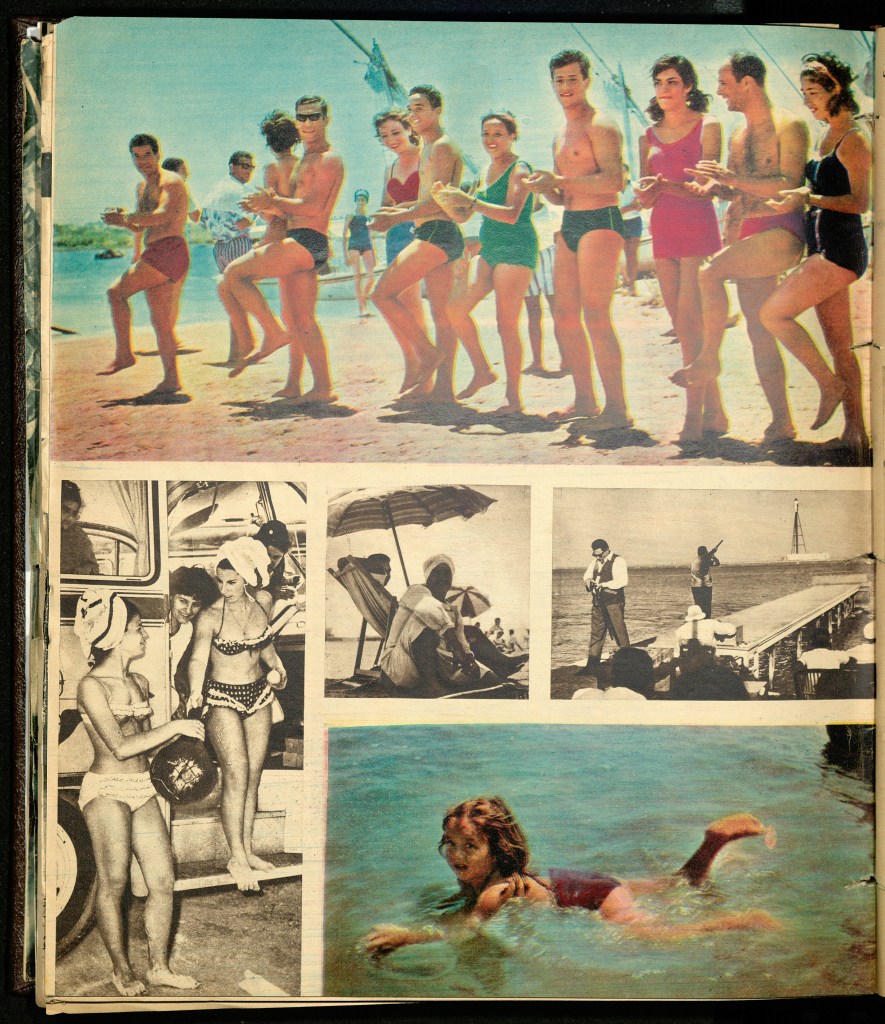

In a 1964 summer issue of al-Musawwar titled “What people do…” candid photographs show everyday people playing games, flirting, dancing, swimming, and chatting (Figures 7-8). In some ways these images are very similar to those from 1931’s Images: they showcase small intimate groups, especially women, and long expanses of beach. Young women wear bikinis in bright colors, dance, and “make merry all day,” as the caption indicates. In other ways these images are quite different. Notably there is a diversification of representation. Older people are included; in this case a grandmother, perched on a chair set in the waves, plays with her grandchildren. Members of the working poor and working class are also represented, such as the man with an umbrella in a small image in the crease. The caption reads: “A peasant (ragal min al-reef) spends summer at the sea.”[16] The inclusion of different types of people is a notable difference from 1931 Images and aligns with aspects of the political and social changes of President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s socialist regime.[17]

A 1954 issue of Bint al-Nil is overtly political in its critique of these lighthearted representations of women and beaches. An article titled “If the Tables were Turned…” juxtaposes photographs of women in fashionable summer clothes along the water with cartoons of men doing household chores.[18] The juxtapositions do sly political work, pointing out the discrepancy in expectations regarding women’s and men’s time, as well as poking fun at the assumptions depicted by fashion spreads in popular fashion magazines. Women may lounge all they like on the pages of magazines, but their presence at the beach in reality is more suspect, and exposes women to verbal abuse and conservative criticism.[19]

Songs and Films: Romance and Intrigue on the Beach at Alexandria

Mid-century musicals incorporated beach excursions, often with choreographed dance numbers. Songs sometimes metaphorically elaborated on romantic plots. In The Fun Band from 1970, for example, the catchy song “On the Sand” comments upon the budding romantic entanglement of the main characters, played by Mohamed Roushdi and Shams al-Barudi.[20] In the scene, Roushdi sings on the beach to al-Barudi, accompanied by swimsuit-clad men and women performing a choreographed dance. The lyrics and choreography are a clever acknowledgement of the many pleasures and dangers of the beach—a combination of waves, friends, secrets, flirtatious gestures, and fair-weather romance that fades with the summer, like sandcastles washed back to sea. There is little attempt to moralize beach sociability in this film. This is not the case in other examples, however.

In Abi Fawq al-Shagara (“Dad’s up a Tree”) from 1969, the beach is a moralized theatrical landscape. Protagonist Adel, played by Abdel Halim Hafez, leaves home to spend a few weeks at Alexandria’s beaches with his friends.[21] Their time is filled with good, clean fun—defined by dancing, burying each other in the sand, and lighthearted conversation. However, Adel becomes frustrated that his girlfriend, Amal, won’t make time to be alone with him and refuses his kisses. In response, he drifts towards a group of acquaintances gathered apart from his friends. With them, Adel finally agrees to take a sip of alcohol, after at first saying “I don’t drink.” This is the beginning of his moral downward spiral, as he moves away from the sun-soaked beach into the cabaret and falls for the dancer Firdaws. The dark, smoky, boozy cabaret is the opposite of the wholesome, sun-soaked beach; his drink at the beach functions as the pivotal moment in this moral tale.[22] After Adel realizes the error in his ways, he returns to the beach, running in the waves with Amal. She has changed, too, and agrees to kiss him in the sun. Amal’s decision to change, however, is not clarified.

Uninterrupted Views and Unwanted Gazes

Film stars also contributed to beach culture off the screen. In 1958 movie star, screenwriter, and producer Faten Hamama wrote an essay in al-Kawakib about summering in various locations in Egypt (Figure 9). Alexandria’s beaches are lovely, except for the tendency of men to openly stare at any woman along the shore at Anfushi, the oldest part of the city, situated on the peninsula. “Not one of these young men hesitates to stare at whatever beauty they are tempted by.”[23] Her favorite summer spot, however, is at Ra’s al-Bar in Dumyat. This less crowded destination provides a quiet day among ordinary people—nothing offered but what is needed. Hamama demonstrates that the beach, at the edge of the city, was central to conversations about women’s role in post-war Egypt. The images of young women having fun in magazines, candid or staged, were curated and selective. Experiences in real life varied, and women’s bodily autonomy and right to be left alone was unassured.[24]

Conclusion

In the sources I have considered, the beach is a discursive series of representations. It is a multimodal and multivalent modern social space. It was possible to enjoy beaches, to laugh and play with friends. It was also possible to confront moral challenges and unwelcome gazes. By mid-century, the beach emerged as a setting in which to consider modern life, especially in regard to the social status of women and the family. What was proper, anyway? And who had the right to say? It is possible to extend these observations into macro considerations of Nasser-era governance policies and women’s rights movements. Likewise, they can be turned inward to consider the patterns of microhistories and reflect on how people made the best out of everyday life: a constant negotiation between ideal geographies of sun and un-remarked upon play, and the challenges of uninterrupted gazes. In the context of an urban history of Alexandria, these sources show that the beach—ostensibly at the edge of the city—was central to the public’s imagination of it. Women played a key yet unresolved role in these representations.

Alexandra Schultz recently completed her PhD at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her first book project, based on her dissertation, focuses on the everyday experience of water infrastructure development in urban Egypt. Her research appears in PLATFORM, Architecture_MPS, and several edited volumes. Alex is currently a Humanities Research Fellow for the Study of the Arab World Program at NYU Abu Dhabi.

Featured image (at top): Figure 1, Edme-François Jomard, Alexandrie plan général des deux ports, de la ville moderne, et de la ville des arabes (Paris: Impr. Impériale, 1817), New York Public Library.

[1] This essay is part of a larger, in-progress project on social water spaces in twentieth-century Egypt. The research for this project was supported by the University of California at Santa Barbara and the Humanities Fellowship for the Study of the Arab World at New York University Abu Dhabi. I am grateful for feedback on this material from attendees at: the Humanities Research Fellowship Seminar (18 Sept 2023), MESA 2023 (4 Nov 2023), and Confronting Environmental Change in Asia (19 Feb 2024). Special thanks to: Nadia Naqib, Ibrahim Gemeah, Joel Gordon, Salma Shash, and Mark Swislocki. I would also like to thank Zeead Yaghi, Ryan Reft, and the editorial team at The Metropole for curating this series.

[2] For local Alexandrines, this perception seems to have differed. There were complaints about the behavior of tourists during the summer in al-Ahram editorials, such as: Anon, al-Ahram, 23 July 1931, 11. Lebanese author Jacqueline Klat, who wrote about her experiences growing up in Alexandria, noted that they left Alexandria every summer to avoid the Cairene vacationers. See: Jacqueline Klat Cooper, Cocktails and Camels (Alexandria: Bibliotheca Alexandrina, 2008), 35. Even today, Alexandrines tend to steer clear of the beach in summer.

[3] Gratien Lepère and E. Collin, Alexandrie. Carte générale des côtes, rades, ports, ville et environs d’Alexandrie, 1809, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b101010885.

[4] The canal was renamed the Mahmudiya Canal soon after its completion. For the Mahmudiya Canal and environmental history of the Ottoman period in Egypt, see: Alan Mikhail, Nature and Empire in Ottoman Egypt: An Environmental History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), chapter six.

[5] Mahmud Hamdi al-Falaki, Kharitat al-Iskandariya fi sina 1282 hijri, 1865, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10104413k.

[6] William McLean, City of Alexandria Town Planning Scheme, 1:12,500, 1921, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/01448ee0-e0f4-0134-ae63-02d713d062a3.

[7] See: William McLean, City of Alexandria Town Planning Scheme: Descriptive Note and Plan (Cairo: Government Press, 1921). For an important local Egyptian architect’s perspective of Alexandria’s planning priorities, including housing for the poor, see: Mahmoud Riad, “Alexandria. Its Town Planning Development,” Town Planning Review 15, no. 4 (1933): 233, https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.15.4.443244u301240682. Also see Mohamed Elshahed, “Workers and Popular Housing in Mid-Twentieth-Century Egypt,” in Social Housing in the Middle East, ed. Kıvanç Kılınç and Mohammad Gharipour (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), 64–87, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvd58s1c.5.

[8] These atlases were graciously provided as digital resources courtesy of Hala Bayoumi and Pascal Menoret at CEDEJ. Mislahat al-Misaha, Muhafizat al-Iskandariya 1:500, ca. 1914-1989.

[9] Alexandria – Stanley Bay Beach, accessed April 5, 2024, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b101128340.

[10] See for examples: Muhammad Basheer, “Hammamat,” al-Musawwar (23 April 1926), 7.

[11] See for example: M.B. de Villepion, “Comment nager le ‘crawl,’” Images (9 August, 1931), 16-17.

[12] See for example: Anon, “al-Sibaha riyadia kamila,” Bint al-Nil no 32 (August 1948): 38; Anon, “Bint al-Nil ta’alamik al-sibaha,” Bint al-Nil (July 1947): 33. Commentary on the benefits of physical exercise could be highly gendered and represent colonial anxieties and nationalist aspirations, as Wilson Jacob has discussed. Wilson Chacko Jacob, Working Out Egypt: Effendi Masculinity and Subject Formation in Colonial Modernity, 1870–1940 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), especially chapter three.

[13] As of publication, Manar Moursi, at MIT in the History and Theory of Architecture program, is currently completing a dissertation on beaches. See her discussion of the mid-century beach as a state-sponsored space to reinforce proper socialization between unrelated men and women: Manar Moursi, “Concrete Shores: Illusions and Desires of Total Control on the Littoral Edge of Egypt,” in Coastal Architectures and the Politics of Tourism: Leisurescapes in the Global Sunbelt (New York: Routledge, 2023): 283–97. Experiencing beaches and pools, as well as any public space, as a woman in contemporary Egypt is a topic of significant discussion and creative practice. See: Kamla Abu Zekri, Yawm lil-sitat (Shahin Film, 2014); “HarassMap | Stop Sexual Harassment,” https://harassmap.org/en/; Salma Shash, “The position of women and feminist movements,” In: An Atlas of Contemporary Egypt eds. Hala Bayoumi and Karine Bennafla (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2023), http://books.openedition.org/editionscnrs/58355. A selection of work on global beaches includes: “The City’s Beach, Run by the People,” July 2023, https://placesjournal.org/article/lincoln-beach-new-orleans-black-and-indigenous-space/?cn-reloaded=1; Debbie Ann Doyle, “Mass Culture and the Middle-Class Body on the Beach in Turn-of-the-Century Atlantic City,” in Gender and Landscape: Renegotiating the Moral Landscape (London: Routledge, 2005); James Freeman, “Democracy and Danger on the Beach: Class Relations in the Public Space of Rio de Janeiro,” Space and Culture 5, no. 1 (2002): 9–28; B. J. Barickman, Hendrik Kraay, and Bryan McCann, From Sea-Bathing to Beach-Going: A Social History of the Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2022).

[14]Identifying whether someone is Egyptian by appearance in these photographs is problematic, and I do not make claims to how these individuals were perceived or perceived themselves. However, it is clear that whiteness as a type was favored in visual representations of the twenties and thirties. Manar Moursi discusses this issue in an unpublished paper: Manar Moursi, “Testing Waters and Oils: Constructions of Modernity and Post-Coloniality in Depictions of Egyptian Mediterranean Beaches, 1930-1970,” unpublished paper, presented at Middle East Studies Association (MESA) Annual meeting, 2-5 November, 2023, Montréal. See also: Mona Russell, “Marketing the Modern Egyptian Girl: Whitewashing Soap and Clothes from the Late Nineteenth Century to 1936,” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 6, no. 3 (2010): 19–57; Lucie Ryzova, “‘I Am a Whore but I Will Be a Good Mother’: On the Production and Consumption of the Female Body in Modern Egypt,” The Arab Studies Journal 12/13, no. 2/1 (2004): 80–122.

[15] Anon, “Les Plages Alexandrines,” Images (9 August, 1931): 12-13.

[16] Husni al-Husayni and Hamdi Lutfi, “Matha yafa‘al al-nas fi…,” al-Musawwar (Summer 1964): 2-11.

[17]Joel Gordon, Nasser: Hero of the Arab Nation (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2012).

[18] Anon, “Lo Intaqalabat,” Bint al-Nil (August, 1954): 8-9.

[19] I want to thank Ibrahim Gemeah for introducing me to Doria Shafiq. See: Ibrahim Gemeah, “Between Islam and Secularism: State, Religion, and Society in Nasser’s Egypt, 1952–1970,” PhD diss. (Cornell University, 2023). Also see: Laura Bier, Revolutionary Womanhood: Feminisms, Modernity, and the State in Nasser’s Egypt (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011).

[20] Fatin Abdel Wahab, Firqat al-Marih (Gomhouriya Films, 1970). The song title “‘Ala Ramleh” can also be translated as “at the beach.”

[21] Hussein Kamel, Abi Fawq al-Shagara (Sawt al-Fann, 1969).

[22] For alternative interpretations: Ifdal Elsaket, “Counting Kisses at the Movies: The Screen Kiss and the Cinematic Experience in Egypt,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 55, no. 2 (2023): 211–37; Joel Gordon, “The Slaps Felt Around The Arab World: Family and National Melodrama in Two Nasser-Era Musicals,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 39, no. 2 (2007): 209–28.

[23] Faten Hamama, “La tabhalaq fi al-anfushi, wa la tatakallim al-‘arabiya fi bur tawfiq, » al-Kawakib (July 1958): 10-12.

[24] For a more direct consideration of women’s experiences of being harassed in public space in contemporary popular magazines, see: Abd al-Nur Khalil, “Fatat wahida taqif amam al-sinima: matha yadith li-ha?” al-Musawwar (15 July 1966): 16.