Editor’s note: This is the second post in our theme for May, Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean.

by Lauren Banko

Public health officers in Palestine could not find Adam Mohammad, a man diagnosed with leprosy. As it did with others in Palestine with the same diagnosis, the department of health wished to monitor Mohammad’s condition. By the early 1940s, his name was known to health officials in Jerusalem although unlike a number of other men and women with the condition, Mohammad’s name never appeared in the nominal rolls of the Moravian Church Mission’s Leper Home in Talbiyeh.

Under the medical directorship of Dr. Tewfiq Canaan and known by Jerusalem’s German speakers and some overseas visitors as Jesus Hilfe, the Moravian Home functioned more or less as a hospital. While Dr. Canaan worked with, treated, and studied adults diagnosed with leprosy (known today as Hansen’s Disease), the home often excluded individuals like Mohammad. While by all accounts Mohammad did have leprosy, he was one of several patients from outside of Palestine that Canaan deemed to have contracted the disease before migrating.[1]

Mohammad was born in Sudan in 1920. By Mohammad’s own account, he lived in various places there and in Egypt from the mid-1930s to the early 1940s. He eventually traveled to Palestine from Egypt to find work as a laborer. Once in Palestine, Mohammad came to Jerusalem, where he settled around 1943. By that point, he demonstrated clinical signs of leprosy and had likely been made aware of the treatment for it offered by the Moravian Home in Talbiyeh. Since district medical officers from the Department of Health frequently recorded cases of suspected and known leprosy, in all likelihood they may have been aware of Mohammad soon after he arrived in Jerusalem. Even though Mohammad did not attend in- or outpatient treatment at the Moravian Home, in June of 1946 he was admitted to Beit Safafa Hospital, presumably to be treated for complications related to leprosy. The medical superintendent of the hospital reported to Jerusalem’s senior medical officer that Mohammad’s source of infection was “probably Sudan.” He stayed in Beit Safafa Hospital for a month, until July 1946, and then he absconded.[2] Despite raising the alarm, public health officials never traced him.

Mohammad’s case is not unique or even striking, but it does point to the medical and bureaucratic networks across urban spaces in Mandate Palestine that had some capacity to track and trace immigrants with either infectious or serious diseases and illnesses. Because he likely acquired leprosy in Sudan, years before entering Palestine, medical officers in Jerusalem had little interest in putting more effort into finding out where Mohammad went after he left Beit Safafa.

Mohammad did not belong to any known urban cluster of leprosy-sufferers in Jerusalem or elsewhere, and because of his transient lifestyle as a migrant worker, it was unlikely he could be confined to the hospital in Talbiyeh. Other migrant laborers with leprosy also drifted in and out of public health officials’ views. Palestine’s public health ordinances stated that persons suffering from a communicable disease—leprosy was considered communicable in the early days of the mandate—who exposed themselves in a way as to present a public health danger would be subject to a fine or imprisonment.[3] For these reasons, migrant laborers with leprosy and other diseases may have benefited from their transiency and their ability to disappear in dense urban spaces. What connects their fleeting stories together are the wider aspects of their existence in Palestine: most settled in urban spaces, like Jerusalem, and in port cities along the Mediterranean. They became incorporated into the urban fabric of these places in ways that workers from within and from outside of Palestine often did: they lived in substandard housing, crowded into apartments with numerous other men, women, and sometimes families. They both moved and worked across cities as their employment and housing circumstances changed.

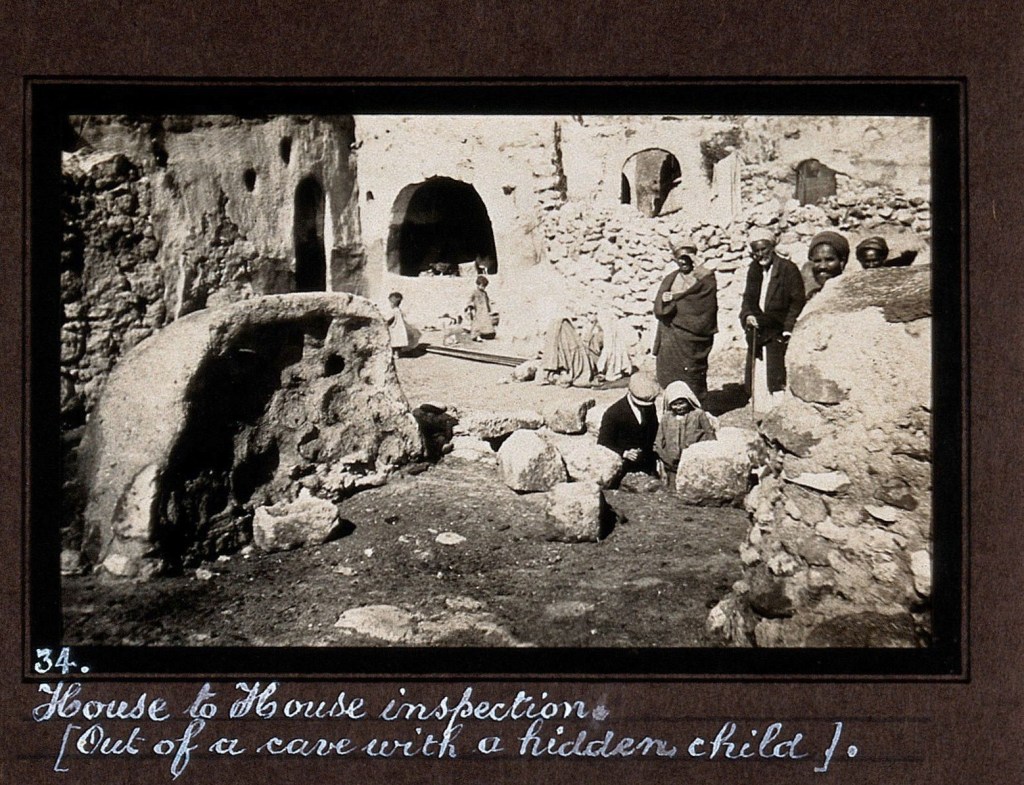

In what follows, I unravel aspects of how migrant laborers’ poverty, immigrant status, and the space of Palestinian port cities funneled these workers into slum housing as well as how these three aspects intersected in providing care for their health, including in terms of how department of health workers oversaw them in rapidly growing and changing cities. This approach offers a sense of the networks that formed around migrant workers in Haifa and Jaffa, in particular, and the ways these urban networks allowed the men, predominantly, to use the space of the two cities and their environs to socialize and evade health, police, and other government authorities. Focusing on migrants with leprosy and typhus means combining the framework of social history with a microhistory approach in order to highlight the more marginal aspects of urbanization in Haifa and Jaffa: regional migrant wage laborers and their health.

In the case of Mahmoud, another immigrant suffering from leprosy who came to Palestine from Egypt in the mid-1930s, his drifting in and out of the view of health officers was because the Moravian Home could not accept him as a patient and he had no place else to turn for inpatient treatment. Mahmoud arrived without his family; his wife and child remained in Egypt. When he came to Palestine, he was in his forties and had suffered from leprosy for several years without any treatment. Both Mahmoud and Mohammad took similar paths as migrants to urban port spaces in Palestine; both lived seemingly transient lives with equally transient employment histories. Mahmoud found work in and around the port city of Haifa and appears within the correspondence by different officers and offices across the public health network in Palestine. At the time that he came to the attention of Haifa’s health officials in 1943, Mahmoud was working as a guard at a British military camp. He did not have permanent housing and instead sent and received correspondence through a grocer in Haifa. He had neither gone to a hospital nor seen a doctor, but rather was visited by district health workers. This was not uncommon; camps and temporary settlements within or just outside city limits for seasonal, migrant, and otherwise poorer laborers became a site of intervention for the Mandate administration. In particular, the living conditions in so-called “slums” in and on the outskirts of cities concerned the department of health.

In Palestine’s cities, this combination of poverty, instable or poor housing, transient employment, and illness undoubtedly made the life of urban migrant workers difficult. David, a Yemeni Jew who arrived in Palestine in the early 1930s via Egypt suffering with mild symptoms of leprosy, held several jobs as a laborer across Jewish agricultural settlements, Tel Aviv, and Ramle. In 1936 when he was twenty years old, David’s name first appears in a memo by Jaffa’s senior medical officer, giving his rough location and time spent in Tel Aviv working as a laborer before he had been sent to Jerusalem for admission to the Moravian Home.[4] He appears again in other correspondence among public health officials in the 1940s. By then, David lived with his mother, but the rest of his family remained in Yemen. As his condition worsened, he was unable to work and his mother lost the support of her son’s wages.[5]

Placing the aforementioned combination of factors into conversation with urban history and, in particular, with the history of urbanization in the Middle East in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, reveals significant stories about the formation of networks in these spaces. Urban networks form around socioeconomically disadvantaged immigrants regardless of place or time period, and male and female immigrants use the spaces of cities to not only find work but also to socialize, evade authorities, integrate into new and subversive economies, and to take care of their health and well-being. To be sure, these activities and processes occurred differently in urban spaces than rural ones—Palestine, like colonized neighboring territories, experienced rapid urbanization after the turn of the twentieth century. The ways in which laborers used urban space depended heavily on the perception of that space by colonial authorities in the years before 1948.

The British administrators rarely perceived urban spaces as benign, whether in Palestine or across the colonial empire. Based on observations and cases of illnesses and deaths in the last few years of the British colonial rule over Palestine, the Department of Health urged the administration to reconsider the latter’s plans to expand “slum housing.” The Mandate government wished to continue building more huts for workers and poor migrants in Palestine’s coastal cities in the years before and during the Second World War. This was meant, in part, to prevent the erection of unauthorized structures, such as tin shacks, by individuals and families and to better control the processes of urbanization in places that drew large numbers of poorer workers and their families. Unauthorized structures ran the risk of facilitating the spread of disease, given their overcrowding and poor ventilation. The department of health, however, believed the scheme of creating new housing for these individuals should be done away with altogether.

At the end of 1941, around 700 huts inhabited by Arab workers and their families arose on the immediate outskirts of Haifa. The city’s medical officers described most of them as “extremely insanitary. . . . unfit for human occupation” and stressed that they should all be removed.[6] Yet individuals and families continued to erect huts of wood and tin. The demand for housing for the port’s workers as well as for workers in nearby British military bases, the railway, and the Iraq Petroleum Company’s transnational oil pipeline, continued apace into the 1940s. For these reasons Haifa, perhaps more so than other Mediterranean port cities such as Jaffa, Acre, or Gaza, attracted large numbers of wage laborers from its hinterland and especially from Egypt and Syria. In areas near Haifa and Jaffa ports, even homes described as “clean and well kept” were nonetheless depicted as “chiefly undesirable . . . affording possible harbourage [sic] for rats.” The huts and impermanent housing remained in cities like Haifa and its outskirts chiefly because they attracted casual, low-paid laborers from either rural parts of Palestine or from the surrounding states, like Egypt and Syria. The huts offered cheap accommodation for these male laborers and, in some cases, their families. Their low wages meant they could not rent more sanitary, ventilated, and modern rooms or houses. For instance, one Egyptian laborer in Haifa reported to a district medical officer that he shared a bed with three other men in a house within which 200 people lived.[7]

In the city of Haifa itself there existed what medical officers categorized as “a great deal of slum property.” These were not exclusively huts but were nonetheless reported to be “filthy, overcrowded, [and] should be demolished.”[8] By the early 1940s, the total number of Arab homes already demolished by government order was around 1,500, essentially evicting approximately 1,000 families. In many cases, the demolished homes had stood since the 1920s, when migrants first arrived to Haifa from Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere in Palestine, including the Galilee. By 1931, over 11,000 Arabs lived in tin huts across Haifa.[9] Elsewhere, health workers repeatedly reported outbreaks of sickness in connection with “wretched and miserable conditions.” Outbreaks of typhus, for instance, were reported alongside descriptions of very poor housing, sanitation, and ventilation, and infestations of rats and bugs (likely fleas and bedbugs) in bedding, kitchens, and small work yards.[10] Haifa’s medical officer of health submitted a report on typhus that mentioned a thirty-five-year-old migrant from Egypt who worked in the Customs Office and who lived alone in a “wooden barrack” behind the port’s quarantine station. Sick with typhus fever, the report noted the man’s barrack had no concrete floor, like other huts that surrounded it, and was “dirty and infected with rats and fleas.”[11] Similar depictions emerge from other epidemiological reports from Haifa, most noting that the workers’ houses were unfit for human habitation. Through the 1930s, reports emphasized the connection between typhus, poor housing, and those persons not from Palestine who were “constantly on the move” into and out of urban spaces like Haifa.[12]

In terms of urban public health, we might assume that the residents of substandard housing were not generally men and women who wished to be confined to hospitals and clinics for long-term treatment. Rather, these individuals came to cities specifically for employment in these densely populated urban spaces. Jerusalem’s district health office emphasized in the mid-1940s that Arab laborers from the Hejaz, Transjordan, and Jabal Druze in Syria were “a menace to the health of the Community in other sub-districts” by their frequent leaving the work camps and going to other villages whenever they wished.[13] Although these men likely went through the standard procedures of delousing, bathing, and quarantine, if needed, on arrival overland into Palestine, the Jerusalem district health office emphatically stated that their unsanitary bodies and camps endangered the health of the whole population of Palestine.[14] The same comparison can be made with the male migrants mentioned above who suffered from leprosy. They too came and went between worksites within cities and their hinterlands.

Despite their illnesses, migrant laborers like those named here used the space of the expanding port cities on the coast of Palestine in a variety of ways. Migrants’ social circles created and spurred not only interactions between workers, but also traces of movement that could be picked up by both the departments of health and immigration. The social circle of a twenty-seven-year-old Egyptian laborer, who came to Palestine as a child but nonetheless worked ever since his arrival, included laborers in an orange grove in Jaffa, fellow laborers in military camps near coastal cities, and army contractors and others in a laundry in Deir El Balah in Gaza subdistrict. The man, Ahmed, traveled back and forth to Egypt on short breaks. After one trip to Egypt, he returned to Deir El Balah where an illness began as he resumed work in the laundry. In a severe state of delirium, Ahmed took a bus from Deir El Balah to Jaffa, where he was admitted to a hospital with typhus fever. Ahmed survived, but other fellow Egyptian workers in Gaza district soon traveled to hospitals to the north in similarly ill conditions. Women, too, were not immune from the illnesses that male workers encountered. One Palestinian woman, who lived in a hut near Ramleh and was accused by her relatives of allowing “unknown Egyptians” to sleep with her, fell ill with typhus and received treatment in Jaffa.[15] Leisure—including sex—sustained the same social networks that health workers argued spread illnesses in and beyond tightly packed urban slums.

Itinerant laborers were by no means outside of the bounds of social circles in urban spaces. In fact, their itinerancy led to the expansion of their social connections. Another young Egyptian man living in a hotel in Jaffa fell severely ill with typhus and was admitted to the city’s isolation hospital in early 1943. The man later explained he had been living in various hotels around Jaffa while he worked for army contractors. He frequently met with other Egyptian friends at coffee houses and visited Egyptian relatives where they worked in orange groves in the outskirts of Jaffa. In hotels and in the orange groves, over half a dozen migrant workers slept together in tiny rooms, and each then daily went to their jobs and coffee shops around the city.[16] Like this Egyptian worker and like leprosy-sufferer Mahmoud, mentioned above, migrants used cafés and grocers to not only socialize with other migrants but also to receive mail, visitors, and find housing.

David, the Yemeni laborer with leprosy who lost his wages as his health worsened, ended up in Jerusalem’s Central Prison. Too poor to continue treatment in hospital, health workers decided that rather than allow him to frequent the working-class neighborhoods in and around Tel Aviv and Ramla, David would be better off in a jail cell.

In 1943 the health department wrote to Palestine’s inspector general of police to caution against the potential dangers of infectious and bacterial disease spread in prisons, where migrant inmates supposedly carried more bacteria than the local population. According to the health department’s warning, the main centers for diseases spread in prisons were Jaffa, Haifa, Gaza, and Ramla.[17] Unsurprisingly, these were the four urban or urbanizing parts of Palestine that attracted significant waves of labor migrants from Egypt, Syria, Yemen, and the Hejaz. While David was in Jerusalem’s Central Prison, it is very possible that this space would also have been considered a site of illness. Indeed, he would not have been the only ill man placed in the prison by health workers for lack of other suitable accommodation and to keep him socially confined. David’s story brings me full circle in demonstrating how impoverishment among migrant workers, looming threats of contagious illnesses, and the space of interwar Palestinian port cities channeled these workers into new urban social networks that brought them to the attention of public health officials. The latter sought to end their transiency in dense urban environments and, as was the case with David, thus made links between health and migrant status that required their surveillance, isolation, and then removal from the space of the city.

Lauren Banko is currently Wellcome Trust Research Fellow in Humanities in the Department of History at the University of Manchester. Her three-year research grant is entitled Medical Deportees: Narrations and Pathographies of Health at the Borders of Great Britain, Palestine, and Egypt, 1919-1950. The project examines the impact of the emergent medico-legal border upon refugees, displaced persons, and laborers with physical and psychiatric illnesses and diagnoses who attempted to transit to and/or through Palestine and Egypt from the wider Middle East, and to Great Britain from the Middle East. She completed her PhD in Near and Middle East History at SOAS, London, and is the author of The Invention of Palestinian Citizenship (2016). A social historian who works primarily on pre-1948 Palestine, Lauren is working on her second monograph on subversive and illicit border crossing between Palestine and neighboring territories during the interwar period. Lauren also holds the role of Instructor in the Department of History at Carnegie Mellon University.

Featured image (at top): Isolation hospital near Beit Safafa, Palestine, (1939), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Tawfiq Canaan, “The Distribution of Leprosy in Palestine and the Possibility of its Eradication,” pamphlet (Jerusalem, 1936), Israel State Archive Chief Secretary’s Office (ISA).

[2] Correspondence between Medical Superintendent of Beit Safafa Hospital to Senior Medical Officer Jerusalem, 24 July 1946, ISA M6577/17.

[3] Department of Health questionnaire on Palestine and leprosy, Jan. 1924, ISA M6577/1.

[4] Whether David actually remained in the Moravian Home for treatment is unknown. Memo by Senior Medical Officer, Jaffa, 28 Oct. 1936, ISA M6577/18.

[5] Medical Officer, Jerusalem Central Prison, Report on Leper David Saadeh Damari, May 1946, ISA M6577/17.

[6] Senior Medical Office, Haifa to District Commissioner for Haifa, 22 Nov. 1941, ISA M4157/9.

[7] Correspondence from District Health Office, Gaza, to Senior Medical Officer for Haifa, 11 Mar. 1944, ISA5125/1.

[8] Senior Medical Officer (SMO), Haifa to District Commissioner for Haifa, 22 Nov. 1941, CSO M4157/9, ISA.

[9] Tamir Goren, “Efforts to Establish an Arab Workers’ Neighbourhood in British Mandatory Palestine,” Middle Eastern Studies 42, no. 6 (2006), 919.

[10] Epidemiological report on cases of typhus in Haifa, 29 Oct 1936, ISA M6578/14.

[11] Medical Officer of Health, Haifa: Epidemiological Reports on Typhus Fever, 15 Sept. 1936, ISA M6578/14.

[12] Epidemiological Report on Cases of Typhus Fever, 24 July 1936, ISA M6578/14.

[13] Correspondence from District Health Office, Jerusalem to Director of Medical Services, Dept. of Health, 11 Jan. 1944, ISA M6578/10.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Epidemiological Reports on Typhus, Jaffa District, May 1943, ISA M6578/9.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Correspondence from J. Macqueen to Inspector-General of Palestine Police, 20 May 1943, ISA M5125/1.