Editor’s note: In anticipation of the Society for American City and Regional Planning History’s (SACRPH) 2024 conference to be held in San Diego on the campus of the University of California San Diego, The Metropole’s theme for February is San Diego. This is the final entry. For more information about SACRPH 2024, see here. For previous entries in the series click here.

By John C. Arroyo

For nearly 115 years, Barrio Logan has been the oldest epicenter of Chicano/a/x (Mexican American) and Mexican community in San Diego, a region rich with Mexican history and culture, given its border proximity to Tijuana. Originally named to honor Congressman John A. Logan’s efforts to establish an unrealized terminus for a transcontinental railroad, Barrio Logan—and adjacent Logan Heights to the north—eventually transformed from a primarily industrial port area to a bustling residential enclave for refugees from the Mexican Revolution.[1] The enduring growth of people of Mexican heritage coincided with the evolution of the area’s maritime industry, which set the stage for a series of haphazard land use interventions over the last forty-five years. Lessons learned from the legacy of Barrio Logan’s community planning process reveal a disconnect between residents’ needs and values and municipal visions for the industrial district. From protests to the formation of community coalitions and the establishment of Chicano Park, each strategy serves as a bellwether for other vulnerable communities facing similar land use pressures in San Diego and beyond.

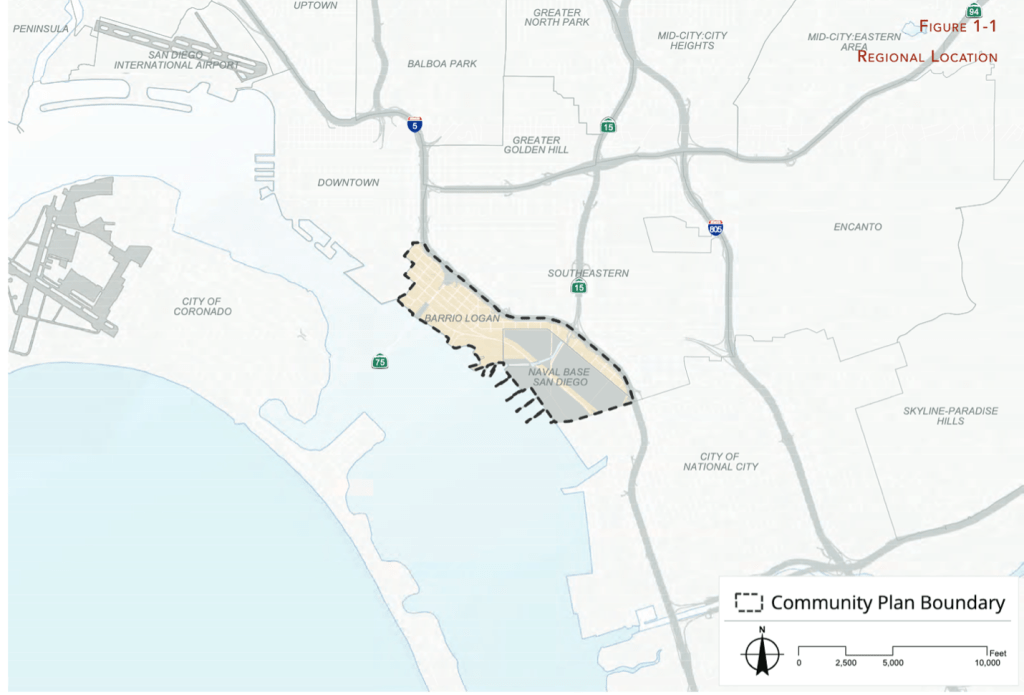

Access to the San Diego Bay made Barrio Logan a prime location for development and expansion during the first half of the twentieth century, especially the growth of the Port of San Diego and Naval Base San Diego, which now cover more than half of the district’s approximately 1,000 acres. A critical flashpoint came in the 1950s and 1960s, when rezoning introduced new industrial land uses to the region (e.g., heavy commercial, maritime-oriented commercial), including the construction of the San Diego–Coronado Bridge (Route 70) in 1963.[2] Apart from the physical gash the San Diego–Coronado Bridge created by bisecting Barrio Logan’s main corridor on Logan Avenue, bridge construction also exacerbated the social isolation residents felt from living adjacent to a heavy industrial zone, fueled the area’s economic decline of several independent businesses on Logan Avenue, and increased the high rates of asthma, diabetes, and other environmentally-induced health hazards.

These consequences resulted in community protests against the State of California. In April 1970, Barrio Logan residents (predominantly junior high to college-age youth and local residents) occupied the land beneath what are now the concrete pylons that hold up the San Diego–Coronado Bridge to halt the construction of a California Highway Patrol station and maintain the space as a park. The grassroots efforts were led in part by Mario Solis, a student at San Diego City College, who rallied other students. The protests lasted twelve days, and upon reaching 250 people, the State of California called off the construction of the patrol station.[3] The high degree of community opposition against the State of California gave birth to Chicano Park, a 1.8-acre (later expanded to 7.4-acre) park famous for its murals of Chicano/a/x history by artists including Salvador Torres, Guillermo Aranda, Mario Acevedo, Victor Ochoa, Tomas Castaneda, Michael Schnorr, and others, later coordinated by the Chicano Park Steering Committee.[4] Over the last thirty-five years, Chicano Park’s prominent history has been formally recognized at the municipal level (San Diego Historic Landmark) and at the national level (US National Register of Historic Places, US National Historic Landmark).

Six months later, a new series of protests took the form of all-night vigils and the takeover of Neighborhood House (1809 National Boulevard, informally known as Big Neighbor) in October 1970.[5] Neighborhood House served as a key battleground for the future of community planning as much as Chicano Park itself, with Chicano/a/x activists demanding community-led empowerment over federal influence. The long-term occupation of Neighborhood House resulted in the establishment of the Chicano Clinic (present day Logan Heights Family Health Clinic) to provide and preserve vital, locally-based social services to the Barrio Logan community.

Over the intervening five decades, various attempts to amend land use and zoning illustrated how Barrio Logan was a model for consequential community planning. When the Barrio Logan/Harbor 101 Community Plan and Local Coastal Program—the district’s first community plan—was finally adopted in 1978, it was suboptimal: light on environmental concerns, which rendered the guiding document obsolete from the start.[6] Instead, the plan and associated zoning ordinance re-established and validated the existing mix of land uses while simultaneously allowing future residential and industrial uses to locate near one another. This exacerbated the district’s existing planning problems and gave a green light for generations of haphazard planning to continue and further endanger the lives of residents.

During the second half of the twentieth century, Barrio Logan endured decades of disinvestment and the bisection of neighborhoods due to highway construction and expanding port infrastructure. The proximity of Naval Base San Diego—the second largest surface ship base in the US Navy—resulted in a proliferation of welders, junkyards, and other toxic diesel-based industries. Their siting adjacent to houses added to the area’s existing pollution concerns, making Barrio Logan one of the state’s most polluted areas, with one of the highest asthma rates (ranking in the 90th percentile of most pollution-burdened communities in California).[7]

In 2013 a short-lived community plan update was adopted by the San Diego City Council to focus on buffer zones that would separate incompatible uses, increase the provision of housing supply, create new public facilities, and encourage new and local retail and commercial uses.[8] Barrio Logan was selected as the first in a series of more than fifty city districts to renew their community plans, given it had been thirty-five years since the last Barrio Logan community plan update. However, the intention to create a buffer zone between the district’s residential and commercial uses was thwarted by a 2014 petition organized by the shipbuilding industry and ultimately rejected by a citywide vote and referendum.[9] This defeat signaled a need for stronger community participation at the grassroots level and catalyzed the Barrio Logan Community Planning Group, which with the help of the Environmental Health Coalition succeeded in getting the local shipbuilding and ship repair industry to sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to envision four new areas in Barrio Logan where industry and housing would not overlap.[10] However, without the legal authorities afforded to the City of San Diego, this vision was more aspirational than enforceable. Two years later, a revised plan began a new draft process, with increased community input from various sectors. It took nine and a half years before a full update of the 1978 Community Plan was drafted.

The recent Barrio Logan Community Plan (2023) is the result of a decades-long fight led by community and environmental justice advocates to guide the future development of Barrio Logan over the next twenty to thirty years. Perhaps its strongest element is creating a sixty-five-acre buffer zone between housing areas and the shipping industry that prevents any new or expanded industrial uses.[11] Other key elements include tripling the amount of new home construction, more transit-oriented and mixed-use projects, restricting truck traffic, redirect port-related traffic, building eight new parks, respecting historic and arts and cultural resources, planting street trees, and improving local economic development. The new plan also allows for more development flexibility, that encourages nonprofit developers, like community development corporations and community land trusts, to play a role in shaping the district through inclusionary zoning and other separations from harmful industries. Since approving the plan in 2021, the San Diego City Council was forced to alter the plan to include fifty-three modifications, including two key policies to accommodate the California Coastal Commission’s requirement to protect low-cost hotel options and prevent displacement.[12]

In December 2023 the California Coastal Commission granted final approval of the new Barrio Logan Community Plan, two years after the San Diego City Council initially approved the plan. A wholesale update to the original Barrio Logan/Harbor 101 Community Plan and Local Coastal Program of 1978, the new Barrio Logan Community Plan offers a planning precedent to other historically disadvantaged Mexican, Mexican American, and ethnic and racial communities across San Diego and the United States. While the consequences a century of extant land use challenges will continue to endure, lessons from the new Barrio Logan Community Plan illustrate how small, self-reliant communities can work together to determine their own future while balancing competing visions between housing and industry.

For more info on the legacy of community plans in Barrio Logan, please visit the following ArcGIS StoryMap: Updating Land Uses in Barrio Logan (City of San Diego, 2020). You can access the Barrio Logan Community Plan (2023) here.

John C. Arroyo, PhD, AICP, is an Assistant Professor in Urban Studies and Planning and Chicanx and Latinx Studies at the University of California San Diego. Previously, he was Assistant Professor in Engaging Diverse Communities and the Founding Director of the Just Futures Institute for Racial and Climate Justice at the University of Oregon. Arroyo’s research focuses on the political and cultural dimensions of immigrant-centered built environments in emerging gateways. He received a doctorate in Urban Planning, Policy, and Design from MIT and currently serves on the boards of the Public Humanities Network (Consortium for Humanities Centers and Institutes) and the School for Advanced Research. His scholarly and applied research has been published in the Journal of the American Planning Association, Journal of Planning Education and Research, Planning Theory and Practice, Urban Affairs Review, Cityscape and featured on national media outlets such as the Los Angeles Times, NPR, and U.S. News and World Report.

Featured image (at top): Barrio Logan Gateway with San Diego-Coronado Bridge (Route 75) in the background. Roman Eugeniusz, photographer, 2015.

[1] “Barrio Logan & Logan Heights: Shipbuilding, Murals and a Mix of Culture.” San Diego Union-Tribune, October 8, 2020.

[2] City of San Diego. Bario Logan Community Plan. San Diego: 2023.

[3] Philip Brookman, “El Centro Cultural de la Raza, Fifteen Years,” in Made in Aztlan, Phillip Brookman and Guillermo Gómez-Peña, eds. (San Diego, CA: Centro Cultural de la Raza, 1986).

[4] Bill Mason, “Original Artists Work to Restore Chicano Park Murals,” San Diego Reader, July 4, 2012, accessed September 5, 2012.

[5] “Neighborhood House,” Chicano Park Museum, https://chicanoparkmuseum.org/logan-heights-archival-project/neighborhood-house/, accessed February 22, 2024.

[6] City of San Diego, “Barrio Logan/Harbor 101 Community Plan” (San Diego, CA: City of San Diego) 1978.

[7] Emily Alvarenga, “Coastal Commission Approves Long-Awaited Barrio Logan Plan,” San Diego Union-Tribune, June 22, 2023.

[8] Patrick Sission, “Barrio Logan Prioritizes Heritage, Housing, and Health in New Plan.” Planning Magazine, March 31, 2022, https://www.planning.org/planning/2022/winter/barrio-logan-prioritizes-heritage-housing-and-health-in-new-plan/.

[9] Roger Sowley, “Shipyards Launching Referendum on Barrio Logan,” San Diego Union-Tribune, October 2, 2013.

[10] Alvarenga, “Coastal Commission Approves Long-Awaited Barrio Logan Plan.”

[11] City of San Diego, “Barrio Logan Community Plan.”

[12] Emily Alvarenga, “After a Decade in Limbo, the Plan for Barrio Logan’s Future Just Got its Final Stamp of Approval,” San Diego Union-Tribune, December 14, 2023.