By Ryan Reft

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has decried the racist history of the US Interstate Highway System, which obliterated many thriving Black and Brown communities. And earlier this year, Buttigieg announced new efforts at the US Department of Transportation to address that problematic legacy, dedicating $1 billion to “reconnect cities and neighborhoods racially segregated or divided by road projects.”

Buttigieg’s efforts were quickly assailed by critics who lamented the “wokefication” of the interstates.

Why so much resistance to a statement of historical fact? We live in an era when narratives—particularly in politics—matter more than ever. With the Interstate Highway System turning sixty-seven this year (retirement age, according to the federal government), it provides a moment to explore the narratives we’ve built around its history. Those narratives obscure the reality of the interstates’ devastating impact on communities across America—impacts that were foreseen and often intended.

Unprecedented in its size and scope, the 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act was, at the time, the single-biggest federal infrastructural investment in the nation’s history. From 1958 to 1966 it was the largest source of federal funding to the states, and it reshaped the nation in countless ways.

In the nearly seven decades since the Act’s passage and enactment, automobility—and the network of highways that enabled it—quickly became a central part of the American narrative. Popular depictions of automobility and the interstates vary. But the idea that the national highway system functions to connect citizens geographically, economically, and socially emerged as a dominant theme.

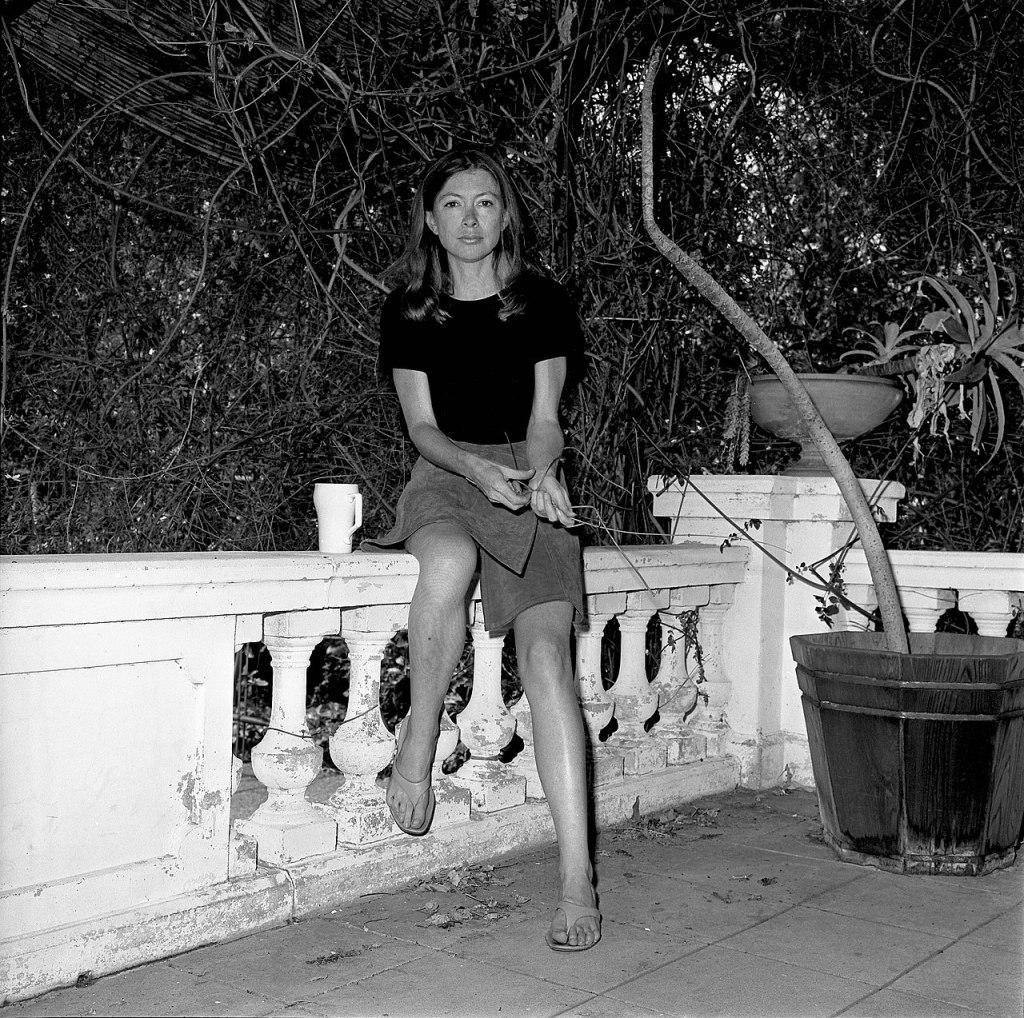

Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) established one of the first and most lasting testaments to the promise of the open road, a story that graphed easily onto the interstate reality that followed. During the 1960s, Joan Didion famously referred to driving Southern California highways as “secular communion.” By 1971 Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell observed that “losing one’s driver’s license is more serious for some individuals than a stay in jail.” Highways had come to encapsulate American freedom, community, and economic success.

Author Joan Didion in Los Angeles on August 2, 1970. Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection, University of California, Los Angeles, Library, Department of Special Collections, CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Yet, Didion also once dourly observed, “we tell our selves stories to live”—a quote that has been widely misinterpreted as a celebration of humanity. Rather, Didion meant it as an indictment. We tell ourselves stories to make ourselves feel better, to sanitize an unpleasant or unjust past: “We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices.”

To Didion’s point, the narratives we’ve told ourselves about the interstates ignore and obscure the fissures they created and the uneven sacrifices placed on non-white communities. From 1957 to 1977, nearly one million people lost their homes to highway construction. And over the past three decades, some 6,300 families were displaced by the nation’s twenty-two largest highway expansion projects. The Interstate Highway System hardwired itself into the physical and cultural reality of this nation, at great cost. Deconstructing the myth behind its creation and putting forth ideas for the future serves as simply the first step in understanding this history and rectifying it.

As urban planner and historian Sarah Jo Peterson writes in Justice and the Interstates, the edited volume published earlier this year based on the The Metropole’s April 2021 theme month of the same title, the sanitized narrative provided by government agencies went as follows: “The Interstate Highways were intended to be a system for intercity (or interstate) travel, but they had unintended effects for cities because they became used inappropriately for travel within urban areas.”

The impact felt by Black and Brown communities—the destruction of community, the loss of housing in an already stratified and segregated market, deprivation of generational wealth, and countless environmental hazards—was frequently blamed on “urban renewal” and corrupt urban politicians, not planners or engineers.

The truth is that planners knew in the 1950s that the interstates threatened urban communities. In 1958 a report by the National Committee on Urban Transportation acknowledged that safety and congestion would be central problems and that “failure to plan for relocation in advance may result in unfavorable public relations and delay the program.”

The same year, the Sagamore Conference—convened by the Highway Research Board and attended by top federal, state, and municipal officials, academics, and civic leaders—issued a report that clearly noted the perils of highway construction. It warned of widespread displacement, with low-income, non-white, and elderly residents facing the “greatest potential injury.”

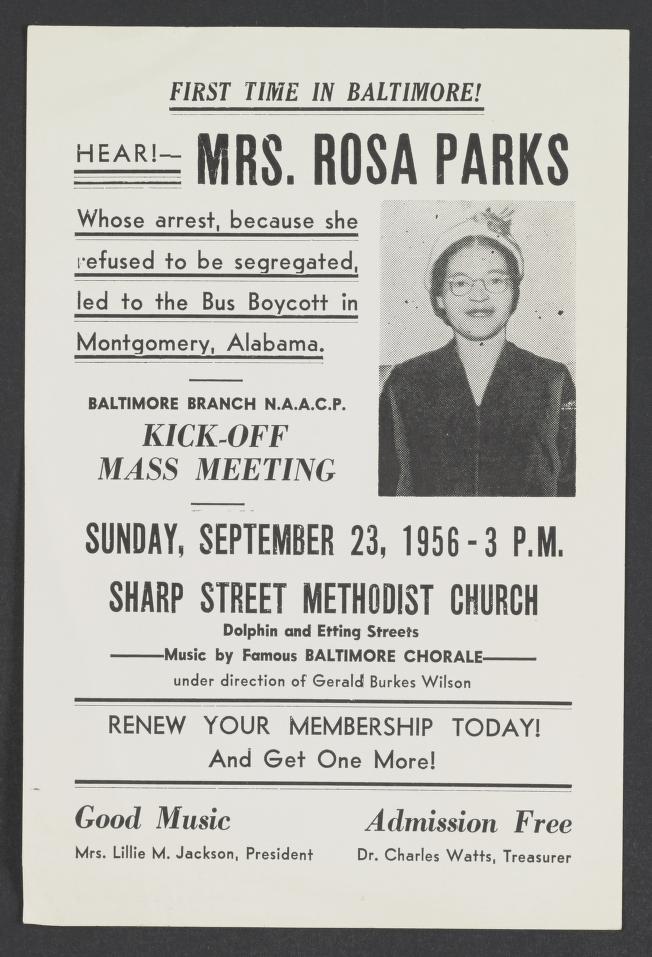

Yet, beginning in the mid-1970s, literature from the US Department of Transportation, which is used frequently in graduate schools and absorbed by aspiring planners and engineers, recast this history as a series of minor, unexpected, and unintended consequences. But often the consequences were explicitly intended and devastating. In Montgomery, Alabama, during the 1950s, for example, Sam Englehart—the man who innovated gerrymandering—punished civil rights activists by running the new highway through West Montgomery, home to Rosa Parks, E. D. Nixon, and others.

Highway proponents argue that mistakes were made due to the newness and scope of the system, but that protests in the 1960s addressed these issues. Unfortunately, the efforts of activists to thwart highway construction failed to benefit Black and Brown neighborhoods. While the “freeway revolts” of the 1960s and 1970s did halt construction in various cities across the United States, this advocacy failed to include non-white homeowners.

Historic preservation laws, enacted alongside environmental ones, have rarely protected historically Black and Brown communities from the highway juggernaut. Of the 95,000 sites on the National Historic Register by 2020, only about 2 percent addressed the Black experience. “The dominant narrative of the freeway revolt is a racialized story” writes historian Eric Avila of this earlier era of resistance. White middle- and upper-class families harnessed resources and connections that simply “did not extend to urban communities of color where highway construction often took a disastrous toll.”

To be clear, working-class white communities were victimized as well. One need only watch Ken Burns’s New York: A Documentary Film, in which former Bronx residents mourn the building of the Cross Bronx Expressway and the numerous ways it corroded community. But white families were not limited by housing or economic segregation like their non-white counterparts. Their burdens were not slight, nor were they as heavy as those of Black and Brown communities.

Untangling the official myth of the interstates’ creation enables communities to envision solutions. In St. Paul, Minnesota, for example, the Reconnect Rondo initiative seeks to recouple two parts of a historically Black neighborhood riven by highway construction in the 1960s. Sarah Jo Peterson and planner Steven Higashide advocate for “truth and reconciliation” carried out, in part, by existing institutions, such as the Transportation Research Board, the utilization of preexisting clusters of University Transit Centers, and/or a Congressional commission to investigate the damages wrought by construction. “If we have any hope of avoiding future injustices, we have to fully understand the past,” notes Higashide.

By deconstructing the official narrative, replacing it with a more accurate appraisal of history, and by providing solutions, perhaps we can address, reconcile, and rectify this history. We won’t have to tell ourselves stories to justify the past; instead, we can live a more equitable present that more fully delivers on the promises made by proponents of the interstates nearly seven decades ago.

Ryan Reft, PhD, is senior coeditor of The Metropole and editor of and contributor to Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth about Urban Highways (Island Press, 2023). He was also coeditor and contributor to East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte (Rutgers Press, 2020). His work has appeared in the Journal of Urban History, Southern California Quarterly, Boom California, and California History, as well as popular outlets such as the Washington Post, Zocalo Public Square, and KCET (Los Angeles).

Featured image (at top): “Sunset over the Soda Mountains and the Barstow Freeway (Interstate Highway 15) east of Baker, California” (2012), Carol M. Highsmith, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Good article–thanks. I would, though quibble with the claim that the freeway revolts “failed to include non-white homeowners.” Many did fight back, and sometimes they won, especially where (as, perhaps, in Boston and DC) they formed alliances with white neighborhoods. This reminds us of the distinction between the overt bigotry of a Sam Englehart and the typical situation in which the nonwhite neighborhoods were ripe for the picking because they had the lowest property values and the weakest political representation. That’s a different kind of racism.

Brian Ladd

LikeLike