This is the fourth entry in our Metropolis of the Month for November 2023, Washington, DC.

By Timothy Kumfer

Standing on the sidewalk with a loudspeaker, Walter Pierce addressed the crowd assembled on the 1700 block of Willard Street, NW. “We’re here today to make clear to the rest of the real estate vultures and land speculators. . .that. . .we will not sit back and watch our community be sold out from beneath us like Georgetown, Southwest, and Capitol Hill,” the 27-year-old chairman of the Adams Morgan Organization (AMO) proclaimed to cheers. Adams Morgan, he declared with resolve, “will remain a place where all of us can live. . .Black, white, and Spanish speaking low and middle income families will not categorically be moved to make way for whites to assume our community.”[1] Equal parts press conference, protest, and party, the November 1973 rally on Willard Street was also one of the first public gatherings to inveigh against a new phenomenon, a process of racialized residential displacement which AMO described as “reverse blockbusting.”

Derided by a Washington Post columnist only a year earlier as the “dismal backwash of the Adams-Morgan area,” Willard Street and its aging rowhouses appeared ripe for reinvestment to D. C. Pope. [2] The developer had quietly bought up homes on the block for between $7,000 and $15,000 each, with plans to sell them for $40,000 following their renovation. The only thing standing in his way were the Black families who lived there, some for three or four decades. In October, Pope’s team delivered an alleged twenty-two eviction notices within a single week. Quickly mobilizing, AMO worked with the residents to win stays of eviction and appointed a team to open negotiations with Pope. While their efforts to secure tenants a right to remain at reasonable rents or purchase their homes at an affordable price were unsuccessful, the press attention from their campaign convinced Pope to walk away from the project altogether.[3]

Emerging from a series of Saturday morning meetings in the fall of 1971 dedicated to discussing problems such as trash, poor housing conditions, and a lack of places for children to safely play, AMO sought to unite their diverse neighborhood behind a set of common objectives. Known for its mix of working-class African Americans and wealthier white residents, Adams Morgan had more recently become home to a growing Latinx community and a countercultural contingent of artists and activists. Bringing residents together across preexisting divides to determine collective priorities, AMO’s biannual (and bilingual) assembly drew the participation of hundreds. To oversee the group’s activities, members elected their own representative council. Within several years AMO’s project committees had conducted multiple street cleanups, converted a vacant lot into a park, formed a food and drug cooperative, and blocked the construction of a gas station.

Formed with the conviction that “the people of Adams Morgan can govern themselves,” AMO’s neighborhood experiment drew on both Black Power ideals of self-determination and New Left impulses for participatory democracy. Several of its founders were veterans of these movements, including Topper Carew, an architect and filmmaker who directed the Black Arts center The New Thing, and Marie Nahikian, a student journalist who covered the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago before moving to Washington. Both were affiliated with the Institute for Policy Studies, a think tank known for nurturing ideas associated with the New Left, and worked with Institute fellow and neighborhood government proponent Milton Kotler to devise AMO’s governance structures. Yet while established to provide its diverse neighborhood with a unified voice, AMO ultimately found itself at the center of conflict over its future. By the mid-1970s, the group’s early emphasis on local sovereignty and self-help took a backseat to urgent campaigns in support of vulnerable tenants, campaigns that required it to take sides and transform city policy.[4]

Following the Willard Street skirmish, AMO and several other groups in the city organized the conference “Blockbusting-1974 Style” in order to get a handle on the changes sweeping DC’s central-city neighborhoods.[5] Reversing blockbusting’s conventional racial iconography while achieving comparable results, real estate agents and developers were forcing out longtime Black and Latinx tenants and pressuring vulnerable homeowners to sell quickly at low prices, only to then turn around and resell the property for twice as much, or more, to white buyers. It was a situation rife with irony, as many of these new white residents were in flight from the homogeneity of the suburbs they grew up in and professed a commitment to racial and economic integration. As Nahikian, at the time chair of the housing committee, remarked, “On Lanier Place, all the available houses are being bought up, renovated, restored, and sold to young couples drawn to Adams Morgan by the very diversity that their overpowering presence will destroy.”[6] In order to protect and defend that diversity, Nahikian and AMO knew they would need legislative support.

1976 fundraising mailer sent to Adams Morgan Organization members urging them to “stand and fight” with the Black tenants of Seaton Street or else “16th Street will be the new Berlin Wall.” Carol & Katie Davis Collection of Adams Morgan Ephemeral, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum

The advent of home rule in the District, which replaced the presidentially appointed mayor and city council with locally elected officials, offered a strategic opening. Over half of the council members seated in January 1975 were former civil rights activists, both eager to put their stamp on the city and indebted to their grassroots supporters. Coming together as the Anti-Speculation Task Force, AMO, the Capitol Hill East Coalition, and others made plans to introduce legislation imposing sharp taxes on properties resold within a short time period.[7] Working with the Tax Reform Group at Public Citizen to draft the bill, their model legislation taxed profits on homes resold within less than a year at rates of up to 70 percent. For example, the gross profit from a home purchased for $20,000 and resold for $50,000 within a year would be taxed at 60 percent ($18,000). Dave Clarke and Nadine Winter, council members whose wards included Adams Morgan and Capitol Hill, respectively, co-introduced the “Real Estate Transaction Tax of 1975” that April.[8]

The Anti-Speculation Task Force organized an impressive showing for the initial hearing on the bill, recounting eye-popping transactions with 230 percent rates of profit and reinforcing how land speculation chiefly benefited white banks and title holders to the detriment of Black tenants and longtime residents. Caught off guard by the bill’s introduction, the real estate industry launched a counterattack shortly thereafter. Black realtors and developers decried the tax, which they argued would undercut their hard-fought entry into the industry and impede Black homeownership. City officials anxious to court private investment also came out against the bill. Marion Barry, then a council member and chair of the Committee on Finance and Revenue, quietly tabled the bill.[9]

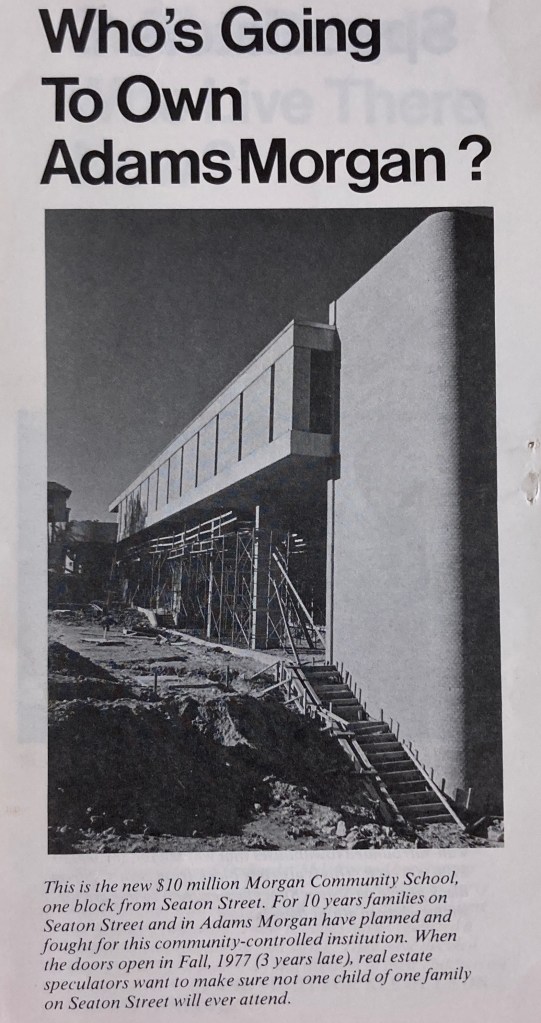

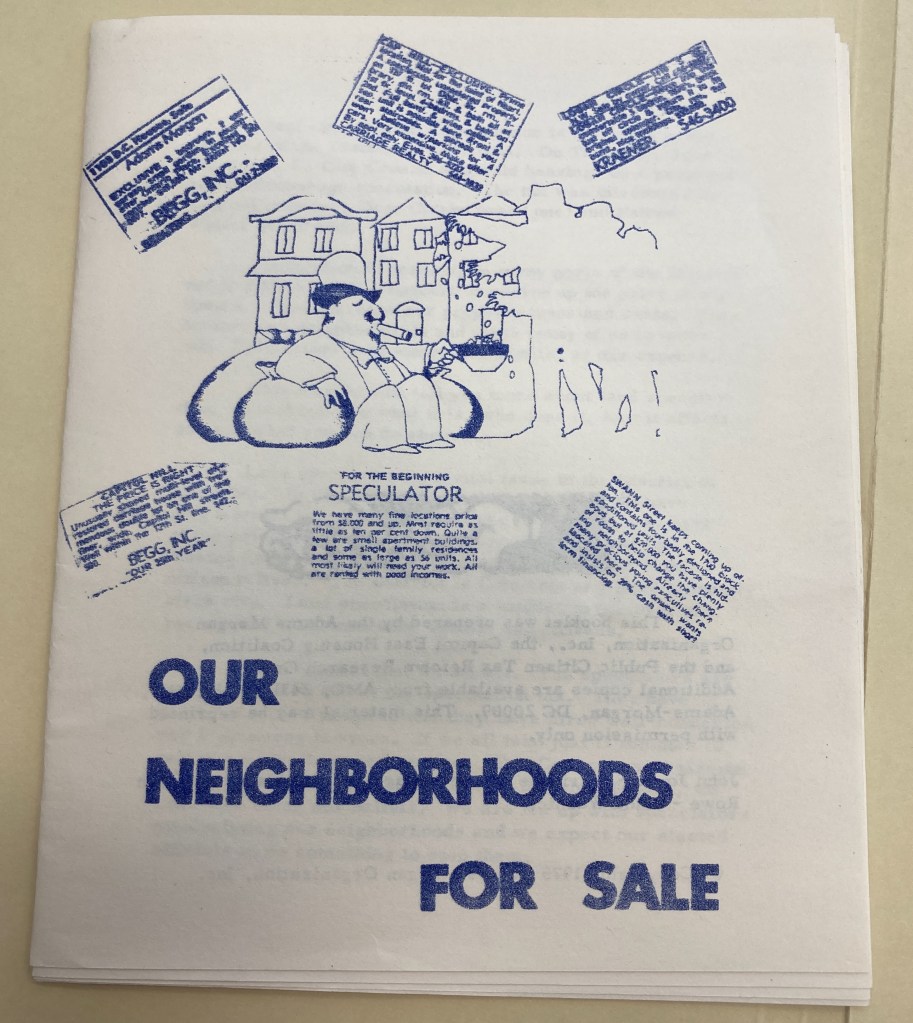

The price of postponement became clear when twenty-six Black households on Seaton Street received eviction notices in the spring of 1976. Located in southeast Adams Morgan, Center Properties had purchased half of the 1700 block with the intention of renovating the properties for resale at around $70,00 each, starting demolition even while tenants remained on site.[10] The situation was reminiscent of the Willard Street fight two years earlier, except this time AMO was ready. Taking advantage of the recently passed Rental Accommodations Act—which offered tenants the right of first refusal when their homes went up for sale—AMO’s lawyers filed an injunction against the evictions and moved to vacate the purchases.[11] Clarke, keen to show he was doing something while his tax bill gathered dust, ordered inspections that found over nine hundred code violations and passed emergency legislation mandating units under eviction orders remain habitable.[12] AMO began fundraising for down payments, urging members to “stand and fight.”[13]

While small-dollar fundraising was a crucial first step, the Seaton Street tenants needed access to substantial capital in order to demonstrate the validity of their offers, a difficult proposition given the redlining practices of Washington-area banks. As the tenants and AMO assessed their limited options, an opportunity presented itself: Perpetual Federal Savings and Loan Association, among the area’s largest thrift institutions, announced plans to open a branch on the prominent corner of 18th and Columbia, NW. When initial overtures to Perpetual on behalf of the tenants gained little traction, AMO explored ways to pressure the bank, including contesting its application to open the new Adam Morgan branch before the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB).

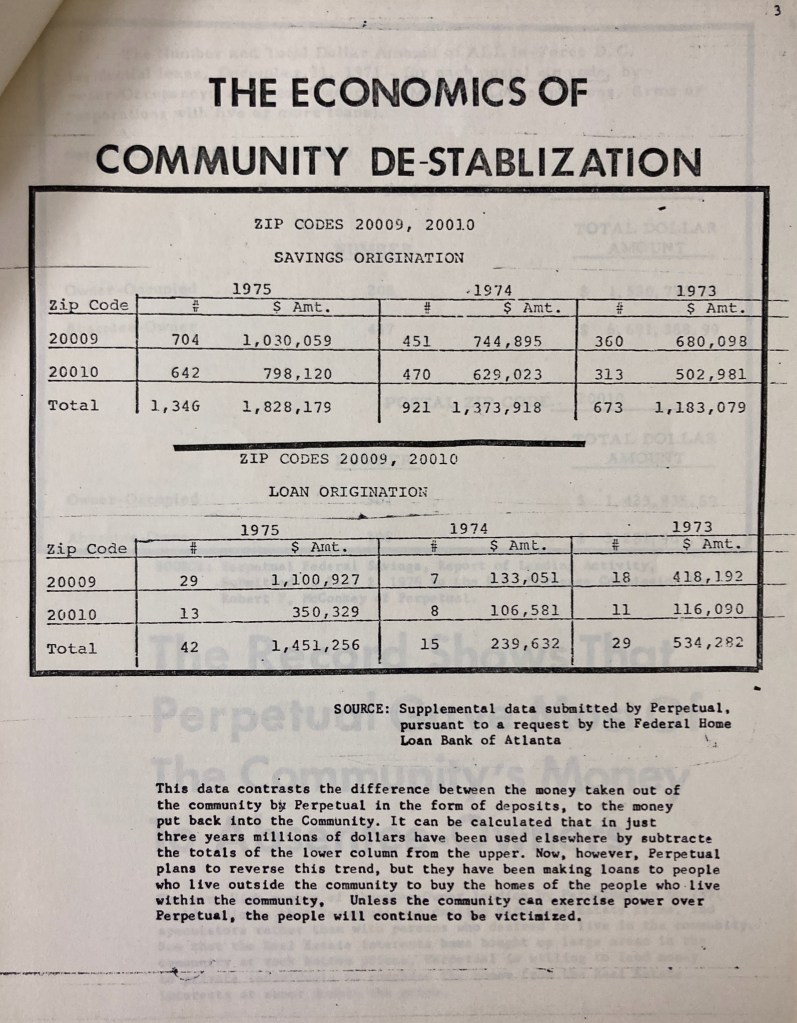

Organizers armed themselves with information from two sources. The local chapter of the Public Interest Research Group, which had just published a study on redlining within the city, provided AMO with data it had found on Perpetual’s disparate lending patterns.[14] The Perpetual Research Group, an initiative led by AMO member Eddie Becker, lent further credence to the claim that Perpetual had historically redlined Adams Morgan, detailing deposit vs. lending ratios of 5-to-1. At the same time, Becker’s investigation revealed a troubling reversal: in 1975 this ratio shrank to 5-to-4 as the bank moved to cash in on the renovation movement and return of white residents to the city, a shift he described as “the economics of community destabilization.”[15]

In the fall of 1976, AMO held a referendum on how the group should respond to Perpetual’s branch application. With 42 percent of respondents opposing the branch, AMO filed an objection to Perpetual’s application with the FHLBB, charging that its mortgage products did not meet the needs of the area’s low- and middle-income residents and that its lending practices discriminated against racial minorities. When their request was denied, AMO chair and former SNCC member Frank Smith flew to Atlanta to testify against the application in person before the board.[16] AMO also recruited others to file petitions against the branch, grinding Perpetual’s application to a halt.

The groundswell of opposition set in motion by AMO eventually brought Perpetual to the table. In July of 1977 the bank assented to a series of demands, including agreeing to provide loans of up to 90 percent for low- and moderate-income applicants and nonprofit cooperatives, fund housing counseling services, maintain a bilingual branch staff, and establish an advisory committee to review loan denials.[17] In exchange, AMO agreed to drop its objection with FHLBB; Perpetual’s application was approved shortly thereafter. That same month, the nine families that remained on Seaton Street throughout the entire ordeal purchased their homes, with Perpetual providing the mortgages and the city agreeing to finance and complete the renovations at a 3 percent interest rate.[18]

AMO’s success on Seaton Street helped to spark a citywide tenants movement and spurred the passage of the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act of 1980. Former AMO organizer Nahikian took a position within the Barry administration, where she helped to build the city’s new Tenant Purchase Program, an initiative that converted over three thousand rental units to cooperative ownership over the ensuing decade.[19] Extending beyond the District’s borders, AMO’s campaign targeting Perpetual informed the drafting of the Community Reinvestment Act, with both the petition against its branch application and proposed agreement featured at Senate hearings prior to the bill’s passage.[20] The deal AMO reached with Perpetual also served as a forerunner to community benefits agreements, a now widespread tool for promoting accountable forms of development.

A year after the Perpetual breakthrough, what AMO hoped would be another tool for keeping vulnerable tenants and owners in their homes resurfaced: the speculation tax. In the three years since its introduction, however, the bill’s stipulations had grown weaker under pressure from the real estate industry. Buildings above four units were exempt, as were owners who sold fewer than three homes. Most critically, an amendment exempted sellers that extended a one-year warranty on the house’s structure and mechanical systems. Highly attenuated and rarely enforced, the bill remained an important precedent as the first tax on urban real estate speculation in the United States.[21]

While AMO’s campaigns formed a bulwark for tenants locally—and contributed to the rise of the community reinvestment movement nationally—long-term trends nonetheless revealed the limited ability of activists to safeguard their communities from real estate capital’s predatory reach. Organizing strategies intended to stabilize neighborhoods, whether providing access to loans in formerly redlined areas or preventing corporate intrusion, at the same time abetted their gentrification. Like bohemian quarters in other cities, Adams Morgan became a harbinger of the transformation to come. AMO, too, was a victim of these changes, with participation in its community assemblies declining significantly by the end of the decade. “Speculation took a double toll,” Nahikian reflected, as those who took the place of lower-income Black and Latinx tenants had less incentive to join the organization: “As people get wealthier, they have less need to cooperate.” Slowly diminishing in influence, AMO ceased operations by the mid-1980s.[22]

The story of AMO corroborates certain aspects within the composite portrait of 1970s cities. As scholars such as Benjamin Looker, Tracy Neumann, and Suleiman Osman have argued, the neighborhood movement (and broader turn to the local during that decade) was ideologically diverse in its origins and often ambiguous in its outcomes.[23] Countercultural desires for urban authenticity commingled with capital’s return to the city; the quest for participatory democracy was freighted with critiques of “big government”; and calls for community self-reliance paralleled the demands of austerity measures. Urban neoliberalism, historians such as Claire Dunning, Brian Goldstein, Benjamin Holtzman, and Julia Rabig have demonstrated, was built from the ground up through experimental citizen activism and not just engineered from above by elites.[24] AMO’s early “DIY” ethos and evolution towards community development broker conform broadly with this outline.

At the same time, an incipient-neoliberalism interpretive angle might obscure as much about the group as it reveals. Initially focused on advancing neighborhood autonomy, the growing crisis of residential displacement led AMO to shift its strategy toward the transformation of city policy. The solutions its members proposed for addressing “reverse blockbusting”—such as taxing away the profits of property speculators almost entirely—were distinctly left-aligned and far-reaching in their implications. Engaging state power as a partner in their campaigns, AMO viewed robust public investment as a precondition for resolving the crisis of housing affordability. Its Black, Latinx, and white coalition also challenges common narratives about the era’s identity politics.

Each of these elements urges a reconsideration of Black Power and the broader New Left’s local lineages in the 1970s. Following these underexplored threads within the existing scholarship can expand our conception of late twentieth-century cities and the multiple forces that shaped them. Doing so might also contribute to the renewal of emancipatory urban politics in our own time.

Timothy Kumfer is a Mellon Sawyer Seminar postdoctoral fellow at Georgetown University. He received his PhD in American Studies from the University of Maryland–College Park in 2023. From 2022-2023 he was a Researching Black Washington Fellow at the DC History Center. His project “Counter-Capital: Black Power, the New Left, and the Struggle to Remake Washington, D.C. From Below, 1964-1994” explores how Black activists and their allies fought for greater control over the city and its future between the War on Poverty and the rise of neoliberal austerity.

Featured image (at top): Postcard advertising 1974 Adams Morgan Organization housing rally. Marie S. Nahikian Papers, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum

[1] Paul W. Valentine, “Inner-City Group Fights Investor,” Washington Post, Nov. 6, 1973.

[2] Wolf Von Eckhart, “The New Resident on Willard Street,” Washington Post, Nov. 6, 1972.

[3] Eileen Zeitz, Private Urban Renewal (Lexington, MA: Lexington Boooks, 1979), 78.

[4] Marie S. Nahikian, interview by Samir Meghelli, July 21, 2017, A Right to the City Exhibition Records, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum.

[5] Duane Shank, “Reverse Blockbusting: Target for Speculators,” The Columbian, June 20, 1974, Washingtoniana Periodicals Collection, The People’s Archive, DC Public Library.

[6] Washington Community Video Center, “Adams-Morgan Gentrification and Displacement Walking Tour,” DigDC, DC Public Library, (original 1972, digital version 2021), https://digdc.dclibrary.org/islandora/object/dcplislandora%3A314797.

[7] Zeitz, Private Urban Renewal, 81.

[8] Paul W. Valentine, “D.C. Real Estate Speculation Tax Urged,” Washington Post, Apr. 2, 1975.

[9] Carol Richards and Jonathan Rowe, “Restoring the City: Who Pays the Price?” Working Papers for a New Society 4, no. 4 (Winter 1977): 55-60; Katie J. Wells, “A Housing Crisis, a Failed Law, and a Property Conflict: The US Urban Speculation Tax,” Antipode 47, no. 4 (2015): 1053-1058. On “landlord power” and the complex political alliances between white and Black real estate actors, see N. D. B. Connolly, A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2014).

[10] Alice Bonner, “26 Families Fight Order to Move Out,” Washington Post, Apr. 24, 1976.

[11] Amiel Summers, “Seaton Place Residents Fight Eviction Notices,” The Columbian, May 1976, Washingtoniana Periodicals Collection.

[12] “Seaton Place Violations Reach 959,” Washington Star, May 18, 1976.

[13] Adams Morgan Organization, “Who Is Going to Own Adams Morgan? Flyer,” 1976, The Columbian Research Files, The People’s Archive, DC Public Library.

[14] D.C. Public Interest Research Group, Redlining: Mortgage Disinvestment in the District of Columbia (Washington, DC: DC PIRG, Institute for Local Self-Reliance, Institute for Policy Studies, 1975).

[15] Perpetual Research Group, “Why Does Perpetual Want to Move into the Adams Morgan, Mt. Pleasant & North Dupont Communities?” 1976, The Columbian Research Files.

[16] “AMO Speaks Out Against Perpetual Branch Office,” The Columbian, November 1976, Washingtoniana Periodicals Collection.

[17] “Loan Policy Agreement Between Perpetual Federal Savings and Loan Association and Adams Morgan Organization et al,” July 1977, Box 1, Marie S. Nahikian Papers, Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum.

[18] Adams Morgan Organization, “Seaton Street Settlement Press Release,” July 14, 1977, Box 1, Marie S. Nahikian Papers.

[19] Amanda Huron, “Creating a Commons in the Capital: The Emergence of Limited Equity Cooperatives in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 26, no. 2 (2014), 59-60

[20] U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs: Hearings on S. 406 To Encourage Financial Institutions to Help Meet the Credit needs of the Communities in which they are Chartered, and for other Purposes, 95th Cong., 1st. sess., 1977, 68-131. On the broader political-economic context surrounding the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act, see Rebecca K. Marchiel, After Redlining: The Urban Reinvestment Movement in the Era of Financial Deregulation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 135-146.

[21] Wells, “A Housing Crisis, a Failed Law, and a Property Conflict.”

[22] Rich Bruning, “Early AMO Years Marked by Much Activity,” Rock Creek Monitor, Mar. 8, 1979, Washingtoniana Periodicals Collection, DC Public Library.

[23] Benjamin Looker, “Visions of Autonomy: The New Left and the Neighborhood Government Movement of the 1970s,” Journal of Urban History 38, no. 3 (2012): 578-581; Tracy Neumann, “Privatization, Devolution, and Jimmy Carter’s National Urban Policy,” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 2 (2014): 283-300; Suleiman Osman, “The Decade of the Neighborhood,” in Bruce J. Schulman and Julian E. Zelizer, eds., Rightward Bound: Making America Conservative in the 1970s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 106-127.

[24] Claire Dunning, Nonprofit Neighborhoods: An Urban History of Inequality and the American State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022); Brian D. Goldstein, The Roots of Urban Renaissance: Gentrification and the Struggle Over Harlem (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017); Benjamin Holtzman, The Long Crisis: New York City and the Path to Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021); Julia Rabig, The Fixers: Devolution, Development, and Civil Society in Newark, 1960-1990 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).