This is the third entry for our November 2023 Metropolis of the Month, Washington, DC.

By Edwin A. Rodriguez

In an interview with news media outlet Bloomberg, science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson reflected on his book Green Earth (2015), inspired by his time living in Washington, DC. He noted that when he lived in the city in the late 1980s and early 1990s, people from all over the world “who were in trouble and needed representation in the world capital” had come to DC. “To go to the world capital and settle there is a statement. It’s an attempt to wrest control of one’s fate.” The history of Salvadorans establishing roots in the nation’s capital and its suburbs is a powerful example of an immigrant community refusing to be left at the margins by immigration policies designed to exclude them from legal protections. Thus, in celebrating fifty years of Home Rule, we should also recognize the rich history of Salvadorans in DC and their own push for control of their own lives.

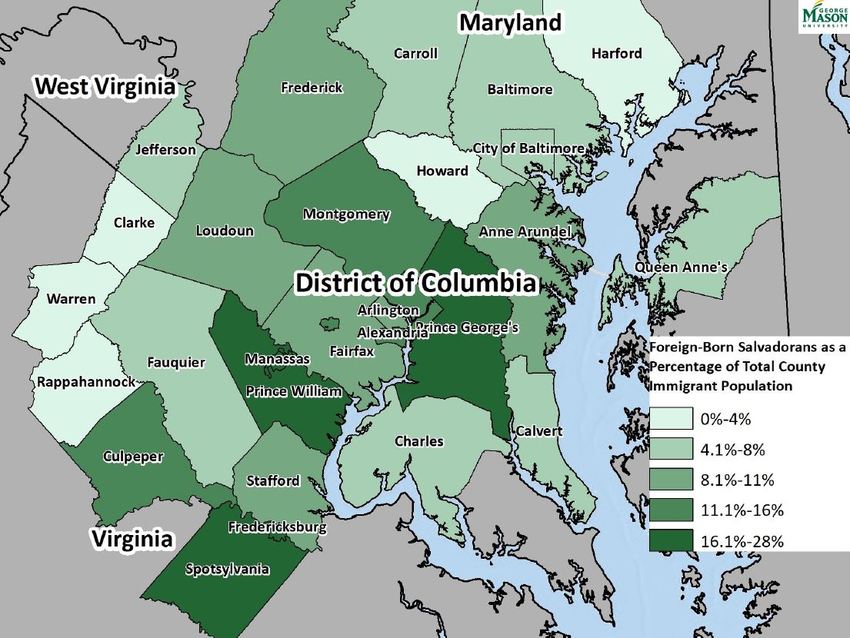

The Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area, colloquially known as the DMV, is home to over 200,000 Salvadorans, which constitutes the second-largest Salvadoran population in the United States and the largest immigrant population in the nation’s capital. While the largest Salvadoran population can be found in California, the establishment of such a prominent Salvadoran community in the DMV provides valuable insight into the region’s political, labor, and economic history. Moreover, it demonstrates the resiliency of an immigrant community that has been historically marginalized since the 1970s. George Mason University’s Institute for Immigration Research created a map to highlight the density of the Salvadoran immigrant population in DC and the DMV region.

The 1970s are a significant decade in DC history, with 1973 marking the passage of the Home Rule Act. In December of 2023, Washington, DC, will celebrate fifty years of Home Rule, commemorating the District’s autonomy and continued push towards statehood. An integral component of this celebration is the analysis of key themes, such as self-governance and full citizenship. But for many DC residents, including Salvadorans, these themes carry a different kind of significance. For Salvadorans, fifty years of Home Rule can be viewed as synonymous with fifty years of community advocacy spurred by federal policies that have led to ongoing political and legal uncertainty. It would be irresponsible to discuss Salvadoran history in DC, and the larger metropolitan region, without also bringing attention to the ways in which thousands of Salvadorans have been subjected to an undocumented status and forced to rely on temporary legal protections, without any viable paths towards US citizenship. This adds a unique layer to the Salvadoran community’s history in DC, as well as a point of reflection when commemorating Home Rule. Adoption of Home Rule and rising support for DC’s statehood have occurred while one of its most important communities has remained stateless.

Salvadoran History

One of the earliest academic texts about Salvadorans in DC is Terry Repak’s Waiting on Washington (1995). The significance of Repak’s work lies in their gender analysis, demonstrating how the first wave of Salvadoran immigration to DC, in the 1960s and early 1970s, was largely made up of women who worked as nannies and housemaids for a growing sector of government employees.[1] This growth in domestic labor was fueled by an economic transformation after World War II and a significant increase in new federal workers who actively recruited Salvadoran and other Central and South American women to work for them, providing childcare and household maintenance. These women established labor networks and community support systems that convinced Salvadorans to continue making their way to the capital in the early 1970s. With Washington’s booming economy and well-established support systems already in place, newly arriving Salvadorans found a wealth of job opportunities in domestic labor, construction, and restaurants. This first wave of Salvadoran immigration would eventually form part of predominantly Central American communities in DC neighborhoods like Mount Pleasant, Adams Morgan, and Columbia Heights.

By the late 1970s, and early 1980s, Mount Pleasant, Adams Morgan, and Columbia Heights had become Central American spaces, operating as a refuge for the hundreds of undocumented folks from the region arriving in the city who needed work and housing. The importance of this refuge increased dramatically in the 1980s, when about one million Central Americans entered the United States, escaping US-funded civil wars. Like the Vietnamese, Iranian, and Nicaraguan refugees before them, Salvadorans and other Central Americans settled in the nation’s capital, the center of the United States’ power and the same place where imperial strategies were unfolding with regard to their country’s future. The history of Salvadoran immigration to Washington, DC, is yet another example of how the United States’ imperial war-making and intervention creates marginalized peoples in the metropole, where power is exercised over them in a continuous project of imperial management.

Ronald Reagan’s $4 billion dollar investment into the Salvadoran military resulted in the displacement of one million Salvadorans (roughly one-fifth of the country’s population) over the course of twelve years, with DC and its suburbs being a prime destination for hundreds of thousands of people. This mass movement ultimately led to Salvadorans becoming the largest Latinx group in the metropolitan region and the third largest Latinx group in the nation. In Covert Capital, Andrew Friedman demonstrates how the suburbs of northern Virginia, in particular, are uniquely tied to the expanding global status of Washington, DC, from 1970 to the early 2000s.[2] Friedman argues that there is a reason why northern Virginia became the site of one of the largest Salvadoran communities in the United States. Salvadoran refugees fled a civil war that was being planned and supported from Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) headquarters, strategically built in Fairfax County, Virginia. By situating themselves in northern Virginia suburbs, the United States government was able to hide militarization and imperial warfare in plain sight—a covert capital. The irony here is that these very same buildings were often constructed and serviced by Salvadoran refugees themselves.

As more Central Americans arrived, the question of whether they should be granted refugee status became increasingly important. For many Salvadorans, being undocumented had defined their lives in the metropolitan region since the 1970s, and many employers were eager to hire them because they knew they could pay them significantly lower wages. The large number of undocumented immigrants and the correlated rise in unauthorized labor resulted in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), also known as the Reagan Amnesty. IRCA did two things: First, it made it illegal for employers to knowingly hire undocumented immigrants. Second, it offered an opportunity to attain legal status. The caveat? Only those who had entered the country prior to 1982 could apply. While thousands of undocumented immigrants qualified, most Salvadorans, who had arrived in the 1980s during the peak of the civil war, were left out. Consequently, Salvadorans in DC became primary targets for deportation as well as for increased exploitation by employers who continued to hire undocumented immigrants, looking to take advantage of their uncertain situation to pay extremely low wages for positions with poor working conditions.

Realizing that Central Americans in DC required legal services and basic human needs, a host of Central American activist organizations emerged in the 1980s and 1990s to provide aid and protection to Central Americans in the metropolitan region. Among these were the Salvadoran Refugee Committee, also known as El Comité, the Central American Refugee Center (CARECEN), the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES), and Casa de Maryland. El Comité operated out of the basement of Calvary United Methodist Church on Columbia Road and distributed food, provided legal, medical, and job placement assistance, and found temporary housing for families. These organizations, although small in their beginnings, became the Central American community’s stanchions for decades to come, advocating on behalf of Central American immigrants and drawing attention to the negative impacts of IRCA. This led to a region-wide sanctuary movement consisting of secular institutions who offered further protection to Central Americans. Patrick Scallen refers to this as “seeking refuge in the lion’s den,” a strong message of resilience and capability in “the administration’s own backyard.”[3]

Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

Maryland cities and towns, such as Baltimore and Takoma Park, emerged as sanctuary cities, leading Salvadorans and other Central Americans to venture outside of DC and establish roots elsewhere in the metropolitan region. Today, Maryland is home to the third-largest Salvadoran population in the United States, with Virginia close behind as fifth largest. According to George Mason’s Institute for Immigration Research, the largest numbers of Salvadoran immigrants in the metropolitan region can now be “found in Montgomery County, MD (43,013), Prince George’s County, MD (42,891) and Fairfax County, VA (34,144).”[4] Although many Salvadorans have been able to find refuge outside of DC, legal issues related to undocumented status continue to pervade many of their lives. Over 32,000 Salvadorans living in the Washington, DC, and Baltimore, MD, metropolitan areas are dependent on Temporary Protected Status, or TPS.

As the name suggests, TPS is a temporary protection available to people from designated countries facing extreme and ongoing armed conflict, environmental disasters, or extraordinary conditions. Created in 1990 by the George H. W. Bush administration as part of the Immigration Act of 1990, TPS allows individuals to obtain temporary refugee status and a work permit, permitting them to stay and work in the United States until they can return to their respective countries. Thus, TPS does not provide an opportunity to obtain permanent US residency or US citizenship. TPS has been a legal lifeline for hundreds of thousands of immigrants, particularly to Salvadorans who became the first beneficiaries the same year the law was enacted.

Unlike the IRCA, there is no way to attain legal status with TPS. Therefore, while TPS has been a legal lifeline of sorts, it has also created an immigrant population at the mercy of policymakers who can easily pull the plug. This was evident throughout the Trump administration (2017-2021), when TPS was continuously placed under threat by members of Congress, even terminating designations for El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, Nepal, and Sudan in May of 2019. It is a cruel way of life, where someone could be protected one day and deported the next. Cecilia Menjivar has referred to this as “liminal legality,” while Susan Coutin has called it “legal nonexistence.”[5] Both terms point to the uncertainty and legal limbo that immigrants must navigate in their daily lives. TPS holders exist in an in-between space that is defined by prolonged precariousness, dependent on circumstances beyond their control.

Establishing Space and Place

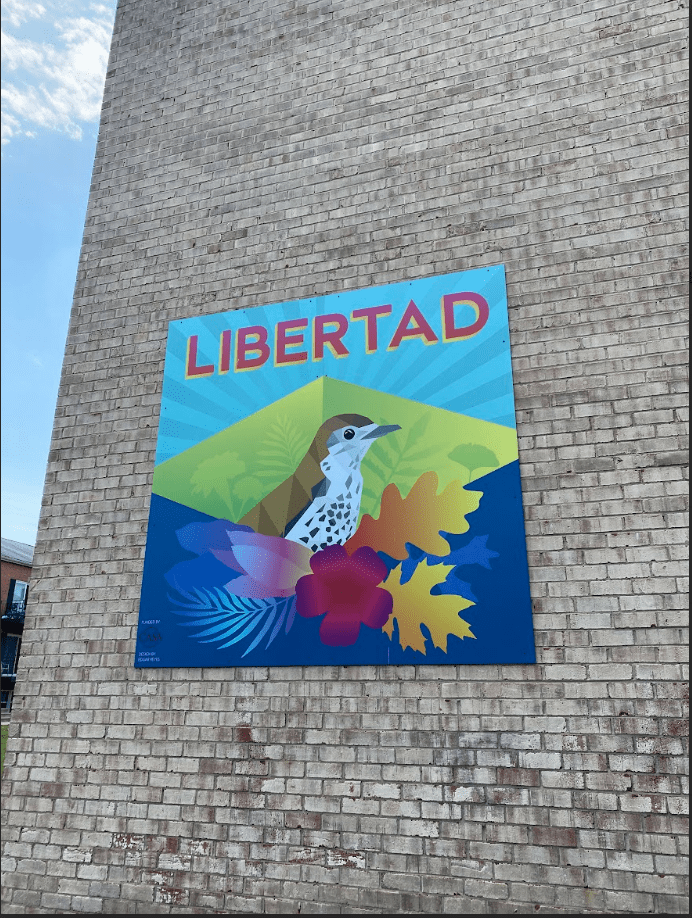

The effects of a temporary legal status on Salvadoran immigrants can be physically, emotionally, and psychologically harmful. Despite this, however, Salvadorans in the DC metropolitan area have established roots and a transnational community that has become increasingly difficult to ignore. Dr. Ana Patricia Rodríguez, for example, highlights the various ways Salvadorans have made significant claims to space within the DC metropolitan area through the production of Salvadoran businesses, such as bakeries and restaurants. She notes, “The popularity of pupusas and the rise in Salvadoran-run restaurants (pupuserias) in the area suggest that Salvadorans are not only becoming more visible in the nation’s demographics and labor force but also transforming social and cultural space and contributing to the economy of the region.”[6] Similarly, oral historian Jose Centeno-Melendez documents how DC’s earliest Salvadoran restaurants marketed themselves “Salvadoran-Mexican,” serving Mexican cuisine as a way to draw in customers and introduce them to Salvadoran dishes.

Dr. David Pedersen draws attention to the historical and transnational connections between Intipucá, a town in eastern El Salvador, and Washington, DC. Pedersen demonstrates how DC has been a popular destination for Intipuqueños since the 1960s, so much so that Intipucá is often referred to as Little DC.[7] This unique connection has resulted in significant development for Intupucá, financially driven by immigrants who want to invest in their hometown through economic remittances.[8] Today, Intipucá exhibits a main plaza called Parque Los Emigrants (The Immigrants Park), with a statue of a migrant heading to the United Sates, in honor of all the Salvadorans who have immigrated to the capital. Intipucá has also benefited in the form of paved roads and newly built houses, a pattern that can be seen in dozens of cities and towns across El Salvador.

In 2019, Krystyn Moon wrote a blog post for The Metropole titled “From Arlandria to Chirilagua: The Shifting Demographics of a Northern Virginia Neighborhood.” Moon describes the immigration history of Arlandria, Virginia, highlighting the rush of Salvadoran immigrants to the area in the 1980s, fleeing from civil war.[9] The number of Salvadoran immigrants that settled in Arlandria was so immense that by the late 1980s Salvadorans nicknamed the neighborhood “Chirilagua” after a town in southeastern El Salvador that many called home—and had also fled from.[10] Today, Chirilagua is home to a diverse community of Central Americans who have maintained strong cultural and familial ties through restaurants, street markets, a Catholic church, Casa Chirilagua (a nonprofit community organization), and international money transfer services.

“We Salvadorans are made of earth and corn, eternal life.”

Salvadorans in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area have maintained a strong sense of identity and community for decades now, while enduring the traumas of a civil war and exclusionary foreign policies. This is a testament to their resiliency and to the immense amount of hope that people hold onto. As we commemorate fifty years of Home Rule in DC, it is important to acknowledge the strength and continued struggles for full citizenship of DC ‘s, and the larger DMV’s, immigrant communities. As DC’s leaders advocate for greater autonomy, many of its residents are navigating a world where their freedom is limited and subject to political swings. Hope as a pillar of community is never lost, however.

In the program for the 1988 Festival of American Folklife, Sylvia J. Rosales, former executive director of the Central American Refugee Center, interviewed Doña Carmen, a Salvadoran refugee who migrated to DC in the late 1980s. Doña Carmen described the difficulties of living in DC, including language barriers, the threat of deportation from employers and landlords, and dilapidated housing in Adams Morgan. Despite these difficulties, however, she stated that “It is better than living with death after you. Life in a war zone is not easy.”[11] Thousands of Salvadorans are still living through these social and economic issues while coming to terms with the harsh reality that a country they call home ultimately wanted them gone. To establish roots in a place that also tells you do not belong is revolutionary, a life-altering endeavor that defies the fate being handed to you. Doña Carmen continued, “Death didn’t destroy us in El Salvador; we can survive this other nightmare now. . .We Salvadorans are made of earth and corn, eternal life.”

Edwin Rodriguez is a PhD candidate in American Studies at Brown University and a Pathways Intern at the National Endowment for the Humanities. Born and raised in Silver Spring, Maryland, his doctoral work is heavily influenced by his family’s experience as Salvadoran immigrants living in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Area. His dissertation, “Siempre Esperando: Technologies of Displacement in El Salvador and the DMV,” centers the voices and lived experiences of Central Americans at the margins to demonstrate the financial hardships both groups endure in the remittance-sending process. He earned his MA in Public Humanities from Brown University in 2020, where he curated a photography exhibit that highlighted his work in El Salvador and the varying forms of waiting that take place when one is expecting a remittance. Previously, he was an intern in the Archives Center at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, where he helped archive the Frank Espada Photograph Collection, 1962-2008. He enjoys biking, tennis, and reading science fiction.

Featured image (at top): Restaurant in Chirilagua, Virginia, named after Cuscatlan, El Salvador’s smallest state and located near the capital. Photograph by Edwin A. Rodriguez, 2022.

[1] Terry A. Repak, Waiting on Washington: Central American Workers in the Nation’s Capital (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

[2] Andrew Friedman, Covert Capital: Landscapes of Denial and the Making of U.S. Empire in the Suburbs of Northern Virginia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

[3] Patrick Scallen, “‘The Bombs That Drop in El Salvador Explode in Mount Pleasant’: From Cold War Conflagration to Immigrant Struggles in Washington, DC, 1970-1995” (PhD diss., Georgetown University, 2019), 168.

[4] “El Salvador: Salvadoran Population in the Washington, DC, and Baltimore, MD, Metro Areas,” George Mason University, Institute for Immigration Research, accessed August 7, 2023, https://iir.gmu.edu/immigrant-stories-dc-baltimore/el-salvador/el-salvador-salvadoran-population-in-the-washington-dc-and-baltimore-md-metro-areas

[5] Cecilia Menjívar, “Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants’ Lives in the United States,” American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 4 (2006): 999-1037. Susan B. Coutin, Legalizing Moves: Salvadoran Immigrants’ Struggle for U.S. Residency (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2003).

[6] Ana Patricia Rodgriguez, Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literatures, and Cultures, 1st ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 178.

[7] David Pedersen, American Value: Migrants, Money, and Meaning in El Salvador and the United States (Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2013).

[8] In Financing the Family: Remittances to Central America in a Time of Crisis (2013), Gabriela Inchauste and Ernesto Stein define economic remittances as “funds sent by emigrant workers to persons, usually family members, in their home country. More importantly, remittances are a lifeline for many poor households” (p. 1). In 2022, El Salvador received $6.9 billion in remittances, which makes up over 25 percent of the country’s GDP.

[9] Krystyn Moon, “From Arlandria to Chirilagua: The Shifting Demographics of a Northern Virginia Neighborhood,” The Metropole, February 11, 2019, https://themetropole.blog/2019/02/11/from-arlandria-to-chirilagua-the-shifting-demographics-of-a-northern-virginia-neighborhood/.

[10] About an eighteen-minute drive from Intipucá, Chirilagua is a municipality that has experienced its own fair share of urban development funded by economic remittances. In the last decade, Chirilagua has transformed itself into a popular tourist destination along the southeastern coast of El Salvador as well as a commercial finance center.

[11] Sylvia J. Rosales, “Of Earth and Corn: Salvadorans in the United States,” Festival of American Folklife Program Book, Smithsonian Institution, National Park Service, June 23-27/30-July 4 1988.