This is the second entry in our Metropolis of the Month for November 2023, Washington D.C.

By Kyla Sommers

In response to the assassination of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, African Americans took to the streets in more than one hundred American cities. The rebellions in Washington, DC, resulted in the most property damage, arrests, and federal troop involvement. Enraged crowds started more than one thousand fires. But what happened after the smoke cleared?

To date, the post-uprising beliefs and politics of suburban, middle-class, white Americans have received more analysis than those of urban, working-class African Americans. Historians have documented how white suburbanites reshaped American politics as they rejected the civil rights movement and Great Society liberalism. The current popular and scholarly narratives alike posit white flight and urban decay as the primary legacies of these uprisings.

This is an insufficient and incomplete history of the 1968 DC rebellions. It overlooks how the majority-Black city’s populace worked to aid their communities during the uprisings and to rebuild a more just District in the aftermath. Building on decades of organizing and activism, DC’s government, community groups, and citizens loosely agreed on a reconstruction process they believed would alleviate the economic and racial inequalities they considered the root causes of unrest. This framework prioritized Black economic development and reclaimed the preexisting principles of Great Society liberalism, such as “maximum feasible participation” (requirements to involve citizens as much as possible in administering anti-poverty programs), community control, and piecemeal urban renewal. Ultimately, most of these ambitious plans were limited by the Nixon administration’s policies and its waning support for citizen participation programs.

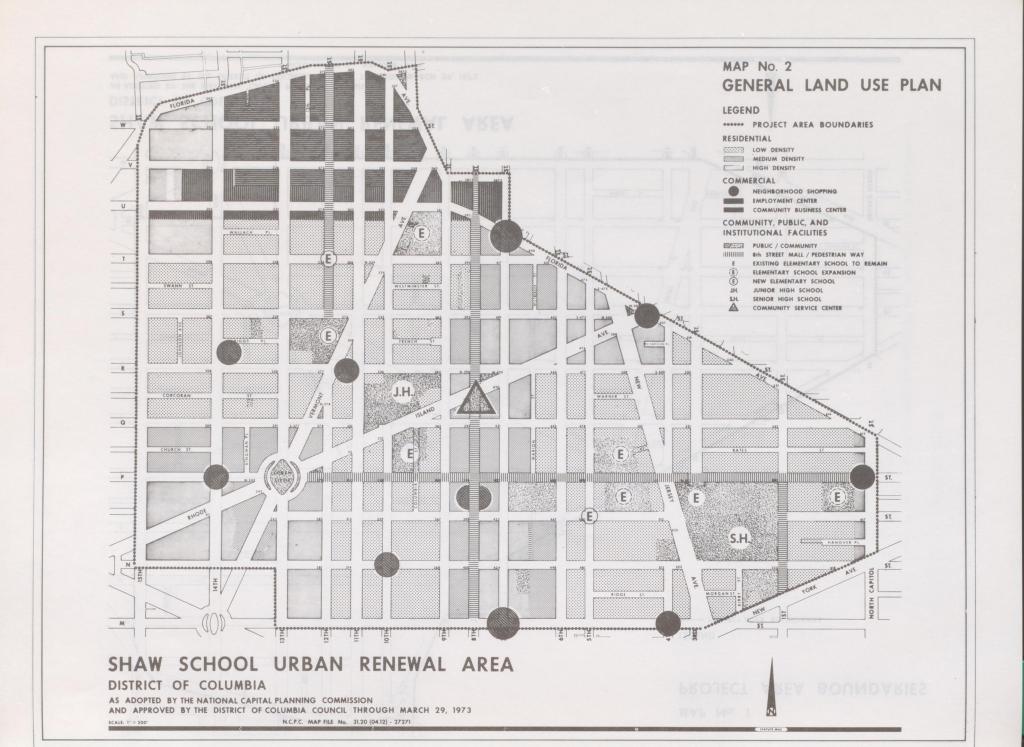

The plan to rebuild DC’s Shaw—the neighborhood that had been the center of Black DC since the Civil War—exemplifies both the promise and constraints of DC’s plan to rebuild. In the early 1960s, the Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) established Northwest #1 and selected it for urban renewal. Haunted by the RLA’s project in Southwest DC that had razed 99 percent of the buildings in the urban renewal area and displaced thousands of Black Washingtonians, civil rights leader Walter Fauntroy created the Model Inner City Community Development Organization (MICCO) in 1966 to give Shaw residents influence over their neighborhood’s redevelopment. In 1967 the RLA hired MICCO to help Shaw residents draft proposals for renewal and be involved in urban planning.[1]

The Shaw neighborhood was the epicenter of the rebellions, and many buildings in the area were damaged. In the aftermath, MICCO surveyed more than 50 percent of Northwest #1 residents to learn how they wanted their neighborhood to be rebuilt. Community members desired a housing plan that would allow them to stay in Shaw, reduce overcrowding, keep housing affordable while improving it, and provide opportunities for home ownership. Of Shaw residents surveyed, 97 percent wanted a subway station that served as a transportation and business hub. One hundred percent agreed with MICCO’s proposal to put “major public agencies like welfare, a health clinic, social security, and local government offices in one central location in or near one of the major shopping areas.”[2]

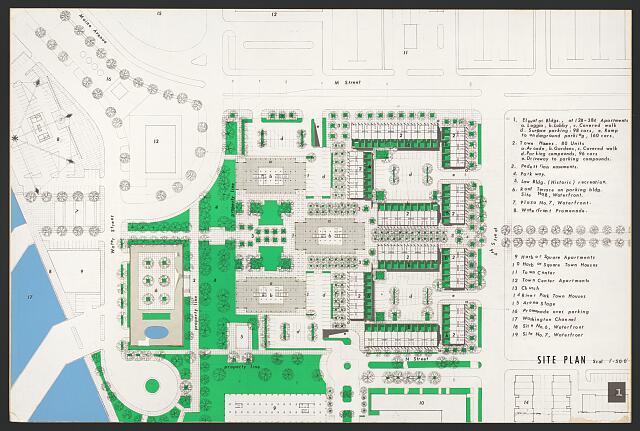

The RLA’s plan, approved by federal agencies and DC in January 1969, incorporated the community’s input. Instead of razing entire blocks, the RLA focused on rehabilitating existing structures and redeveloping in stages. As requested by residents, the design included a subway station, created “social services and community facilities within the Shaw area,” and would locate “major social services (such as health, welfare, and employment) at a centralized point, with other services (such as recreation spaces and day care facilities) being located throughout the area for convenience.”[3] Significantly, the RLA would use nonprofit community groups to rebuild instead of private developers. The DC government—with significant financial support from the Department of Housing and Urban Development—would buy up properties and then sell them to “non-profit sponsors,” primarily community organizations and churches, who were willing to improve properties in line with the redevelopment plan. To help pay for construction costs, the funds paid by the community groups to purchase the properties would be loaned back to them as a Federal Housing Administration loan.[4]

The RLA’s support for citizen participation and community-organization-led development quickly eroded as the projects faced worsening delays. By summer 1970, only one new building was under construction. Two main setbacks caused the delays: relocating displaced people and funding. The RLA was required by law to provide relocation housing for residents whose buildings were reconstructed. But there was almost no public housing or funding available. For example, while the National Capital Housing Authority (NCHA) had planned to provide 1,000 units of low-income housing to relocate temporarily displaced Shaw residents, the NCHA was “bankrupt” and could not deliver.[5] “One of the major factors affecting our ability to accelerate the development process and meet these schedules,” wrote DC RLA head Melvin Mister, “is the availability of adequate relocation resources. By 1971, the lack of relocation housing was so dire Mister insisted that the RLA could not start any new rebuilding projects.[6]

Additionally, to build low-income housing, developers relied on federal mortgage subsidies from the Federal Housing Administration. DC’s RLA financing specialist thought it was “impossible to construct housing that anyone can afford any other way.” As President Richard Nixon vowed to slash funding to “big government” programs, Congress appropriated only $25 million for the nationwide Neighborhood Development Plan in 1969. $129.9 million worth of projects were already backlogged, awaiting money. Making matters worse, Nixon put a moratorium on new construction of subsidized housing in 1970. With severely limited funds, it was difficult to finish projects that were underway, and the RLA greatly limited new undertakings.[7]

Nixon had encouraged rapid reconstruction in DC and discouraged community participation throughout his presidency. After Nixon toured the disturbance-damaged areas during his first month in office in 1969, he made it clear that he wanted “action” fast. “No wonder our citizens are beginning to question Government’s ability to perform,” Nixon said. “There could be no more searing symbol of governmental inability to act than those rubble-strewn lots and desolate, decaying buildings, once a vital part of a community’s life and now left to rot.”[8] Nixon blamed the slow progress on community participation. “Nixon Administration sources have said that citizen involvement in planning delays decision-making to a point at which urban renewal has become intolerably slow,” reported the Washington Post.[9] The president showed “little enthusiasm for ‘citizen participation’” and “sought to return most of the power to city halls.”[10]

The RLA lobbied MICCO to support their new proposal, but MICCO had already negotiated an agreement with a Boston-based developer. Fauntroy and MICCO believed their plan to redevelop Parcel A “offered the community the best deal: Eventual ownership of land by two co-sponsoring Shaw churches; a development team selected with MICCO’s advice; employment of Blacks in all stages, and 150 relocation units assured for displaced Shaw residents.” Even though construction could have begun sooner with MICCO’s plan, the RLA rejected this proposal in November 1971 and opened competitive bidding on the land.[13] After this decision, the relationship between the RLA and MICCO quickly deteriorated, and the RLA terminated MICCO’s contract in January 1973. Later that year, the RLA recommended substantially curbing community participation and consolidating urban planning power: “The present diffused responsibilities for urban renewal planning as well as related community development programming should be eliminated.”[14]

Prioritizing private development did not speed up urban renewal or solve the persistent funding and relocation issues. Private firms also could not find anywhere to house the displaced residents. Nixon’s moratorium on subsidized housing construction also affected the private developers who relied on federal funds to build.[15] Ten years after the rebellions, all completed housing was nonprofit sponsored and designed in consultation with the surrounding community. “During the past few years, some of the largest housing developments in the City have come through the cooperation and sponsorship of church and community coalitions working with the city government,” noted the mayor’s report on the tenth anniversary of the rebellions. The section labeled “Private Sector Activities” in the report only listed projects “underway or planned.”[16]

Even though MICCO’s community-centered redevelopment approach was limited by the Nixon administration’s policies, this history broadens our understanding of the legacies of urban unrest. More than 50 percent of Shaw residents were consulted about how they wanted their community to be designed. The blueprint incorporated their feedback and many of those ideas were constructed. The model trusted community groups to create housing that benefited low-income residents instead of just turning a profit. This history provides an inspiring, alternative framework of urban policy and development.

Kyla Sommers earned her PhD in history from the George Washington University. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, the Washington History journal, and the book Demand the Impossible: Essays in History as Activism. Sommers is the digital engagement editor at American Oversight and was previously the editor-in-chief of the History News Network. The author of When the Smoke Cleared (The New Press), she lives in Washington, DC.

Featured image (at top): Southwest Urban Renewal, 4th St., M St., N St., O St., and Water St., S.W., Washington, DC (ca. 1950-1980). The redevelopment of Southwest DC, represented here, became a point of contention for activists when discussing post-1968 redevelopment. Charles M. Goodwin and Associates, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Eugene Meyer, “RLA Sets Bidding on Shaw Land,” Washington Post, November 11, 1971; Elaine Barber Todd, “Urban Renewal in the Nation’s Capital: A History of the Redevelopment Land Agency in Washington, DC, 1946–1973” (PhD diss., Howard University, 1986), 200–230.

[2] Vincent Paka, “Shaw Area Results Show,” Washington Post, February 8, 1970; “Results of the MICCO Questionnaire,” box 25, folder 16: “Questionnaire, MICCO Community Results, c. 1968,” Walter Fauntroy Papers, Gelman Library Special Collections at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

[3] Peter Braestrup, “Fletcher: Riot Area Rebuilding on Target,” Washington Post, April 13, 1969; George Day, “Urban Renewal: A Slow, Painful Process,” Washington Post, July 2, 1969; “Status Report: First Action Year,” box 26, folder 1: “Report, First Action Year, c. 1968,” Walter Fauntroy Papers; “The Shaw Urban Renewal Area Urban Renewal Plan and Annual Action Program,” box 27, folder 4: “Plan, the Shaw Urban Renewal Area, c. 1969,” Walter Fauntroy Papers.

[4] The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development would provide 75 percent of the money and DC the other 25 percent to purchase the properties. The RLA would administer the loan. Riots, Civil and Criminal Disorders, Ninety-First Cong. 3,159–3,169 (1969) (testimony of Edward C. Hromanik); “The Shaw Urban Renewal Area Urban Renewal Plan and Annual Action Program,” Walter Fauntroy Papers.

[5] Eugene L. Meyer, “Renewal Plan Cuts Foreseen,” Washington Post, June 22, 1970. The plan was that the National Capital Housing Authority would subsidize the leases for those one thousand units.

[6] Letter to Terry C. Chisholm from Melvin Mister, June 4, 1971, box 35, folder 1: “14th Street Development,” Walter E. Washington Papers, Mooreland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Library, Washington, DC; Letter to Walter Fauntroy from Melvin Mister, box 24, folder 36: “Correspondence, D.C. Redevelopment Land Agency, 1971–1972, 1974, n.d.,” Walter Fauntroy Papers.

[7] Robert J. Samuelson, “Low, Moderate Income Housing Stalls,” Washington Post, June 15, 1969; 5 Years Later: Riot Areas Not Rebuilt,” Washington Post, April 8, 1973; Letter to Walter Fauntroy from Melvin Mister, box 24, folder 36: “Correspondence, D.C. Redevelopment Land Agency, 1971–1972, 1974, n.d.,” Walter Fauntroy Papers.

[8] William Greider, “President Orders Aid to Riot Areas,” Washington Post, April 9, 1968.

[9] Peter Braestrup and Carl Bernstein, “President Nixon . . . Has Promised Me a . . . Timetable Under Which the Construction in These Areas Would Begin Next Fall,” Washington Post, April 10, 1969.

[10] Peter Braestrup, “Even Messy ‘Model Cities’ Programs Beat a Riot,” Washington Post, June 29, 1969; Kirk Scharfenberg, “Model Cities’ Aid Revised,” Washington Post, March 1, 1972.

[11] Letter to “MICCO Board Member” from James Woolfork, box 24, folder 36: “Correspondence, D.C. Redevelopment Land Agency, 1971–1972, 1974, n.d.,” Walter Fauntroy Papers; “5 Years Later: Riot Areas Not Rebuilt,” Washington Post.

[12] Eugene L. Meyer, “RLA Sets Bidding on Shaw Land,” Washington Post, November 11, 1971.

[13] Meyer, “RLA Sets Bidding on Shaw Land,” Washington Post; letter from Walter Fauntroy to Melvin Mister, July 12, 1971, Walter Fauntroy Papers; letter to Walter Fauntroy from Robert E. Tracey, August 30, 1971, box 24, folder 32: “Correspondence, Melvin Mister, July 12, 1971,” Walter Fauntroy Papers. Letter to Melvin Mister from Walter Fauntroy, August 31, 1971, Walter Fauntroy Papers; letter to Walter Fauntroy from Robert E. Tracey, August 30, 1971, box 24, folder 32: “Correspondence, Melvin Mister, July 12, 1971,” Walter Fauntroy Papers. Howard Gillette Jr., Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, DC (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 185.

[14] Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 185–188; Letter to Walter Fauntroy from Melvin Mister, March 3, 1972, Walter Fauntroy Papers.

[15] 5 Years Later: Riot Areas Not Rebuilt,” Washington Post; Patricia Camp, “14th St. Struggles Back from Riot,” Washington Post.

[16] DC Office of the Mayor, Ten Years Since April 4, 1968: A Decade of Progress for the District of Columbia, 7, F 200.T 46, Kiplinger Research Library Archives, Washington, DC. Camp, “14th Street Struggles Back from Riot,” Washington Post.