This is the fifth installment to our theme for October 2023, Urban Disability, an exploration of the role cities and their residents have played in the expansions of disability rights. See here for a listing of all the posts published on this topic.

By Dan Holland

Sport has long been the leading edge of social change. Jackie Robinson played his first baseball game in the majors seven years before Brown v. Board was decided. The NFL and NBA integrated years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Women athletes had proven themselves decades prior to passage of Title IX in 1972. Sport as the ultimate meritocracy is a conduit for acceptance, a proving ground for athletes seeking to change perceptions of human nature.

But for disabled athletes, progress has been far slower. Though the Paralympic movement has been a mainstay of sport since its first Games in Rome in 1960, more than three decades before passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, urban adaptations for people with disabilities have been slower to materialize.[1] Curb cuts, kneeling buses, and voice announcements at traffic lights are steps in the right direction. But for athletes with disabilities—in particular, those who use wheelchairs—the barriers to creating obstacle-free training and racing options and access to training facilities remain a challenge. The risks for road accidents remain high.

One study concluded that “about 528 pedestrians using wheelchairs were killed in road traffic collisions in the US between 2006 and 2012. This equates to a pedestrian wheelchair user’s risk of death being about 36 percent higher than non-wheelchair users.”[2] While wheelchair and handcycle athletes can use bike lanes, their lower profile makes them harder for drivers to see.

The proliferation of bike lanes helps those with chairs to share the same spaces. But these are rare. For many para athletes, especially those who use wheelchairs (both push-rim and handcycle), navigating city streets alongside cars and trucks is hazardous. Just five years after passage of the ADA, the New York Times reported, “wheelchair racers must contend with certain vulnerabilities while training on the roads. They sit low to the ground, two to four feet above the road surface, and can be more difficult to see than runners and cyclists. Disabled athletes often face problems of maneuverability as they attempt to avoid collisions in traffic.”[3]

In recent years, high-profile athletes have been victims of traffic accidents. In 2011, South African Krige Schabort, described as “a world-class wheelchair racer,” was hit by a drunk driver in Cedartown, Georgia, a small town that reportedly “has many Georgia Department of Transportation designated bike routes throughout, and is a popular bicycling tourist destination.”[4] In 2021, Runners World reported that “Paralympic gold medalist Susannah Scaroni was hit by a driver in a car during training” in Champaign, Illinois, just weeks after topping the podium in Tokyo.[5] During the Tokyo Paralympics, a sight-impaired Japanese athlete, Aramitsu Kitazono, was hit by a self-driving vehicle.[6]

Like the fight for equality in race, gender, and sexual orientation, disabled athletes, many of whom are military veterans, have spent decades trying to earn respect and dignity in sport and in every day life. “Given the chance,” writes David Davis, “they could do everything and anything non-disabled veterans could do: drive a car, hold down a job, buy a home, get married and raise children, and yes, pay taxes.”[7] Their accomplishments not only help drive changes in perception, but changes in the accessibility of cities—on sidewalks, in buildings, in cars, and on public transportation.

Winning helps too. Nowhere has this been more prevalent than in Switzerland, one of the top countries represented at the Paralympic Games. Swiss athletes, such as Manuela Schär and Marcel Hug (aka “The Silver Bullet”), have become some of the most recognizable names in para-athletics, regularly topping wheelchair competitions in major marathons like New York, Boston, London, and Berlin. Their athletic achievements on the road and track elevate the abilities of people who for far too long lingered in the shadow of a negative stigma.

Origins of Para-Athletics

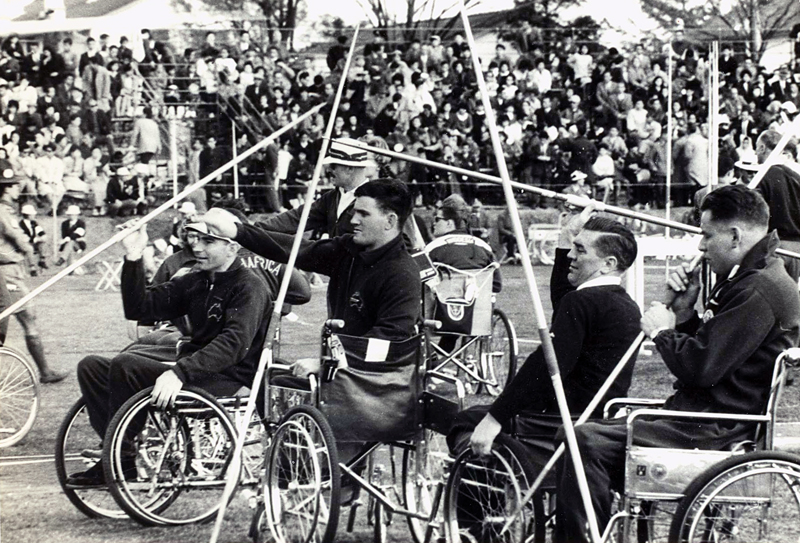

Sport is one of the highest profile opportunities for people with disabilities to earn respect, because sport is based on abilities, rather than class—a pure expression of the Shakespearean quote from The Taming of the Shrew, “’tis deeds must win the prize.” Competition among paraplegics dates to 1948, when British physician Sir Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, who established the National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in England, organized the first competition for wheelchair athletes, the Stoke Mandeville Games. The first Games involved sixte4en injured servicemen and women who took part in wheelchair archery. It quickly grew into a global movement. The first official Paralympic Games, no longer open solely to war veterans, was held in Rome in 1960 and provided an opportunity for athletes with disabilities to showcase that they were fully functioning members of society who could compete at the highest levels of sport. In the inaugural Games, there were four hundred para-athletes from twenty-three countries who competed in fifty-seven medal events across eight sports.

But even the Rome Games ran into urban accommodation problems. Athletes at the 1960 Rome Paralympics “were not treated with the respect and care that the Olympic athletes [who had completed just a week earlier] had received.” From the moment the athletes left the plane—“Authorities at Ciampino Airport extricated the athletes from their DC-8 by means of a forklift truck”—to the athletes’ village, a lack of elevators, inaccessible bathrooms, and useless ramps indicated that the host city was not prepared.[8] In the end, Pope John XXIII offered public prayers for the athletes: “‘You have shown what an energetic soul can achieve, in spite of apparently insurmountable obstacles imposed by the body.’”[9] Still, society was slow to transform the pontiff’s words into urban changes needed for disabled people.

The Paralympic movement has made great strides since then. The first Winter Paralympic Games were held in 1976 in Örnsköldsvik, Sweden (the winter Paralympics is contested in six sports), and global momentum has only grown. Founded in 1989, the world governing body is the International Paralympic Committee, which serves as the International Federation for nine sports: Paralympic athletics, Paralympic swimming, Paralympic archery, Paralympic powerlifting, Para-alpine skiing, Paralympic biathlon, Paralympic cross-country skiing, ice sledge hockey, and Wheelchair DanceSport. Its relationship with the International Olympic Committee was solidified in the 1990s, which gives the Paralympic Games higher visibility. The Paralympic Games involve athletes with a range of physical disabilities, including paraplegia, limb deficiency, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 4,500 athletes competed in twenty-two summer sports at the Tokyo Paralympics in 2021.

Switzerland as a Para-Athlete Powerhouse

Switzerland, a country of just eight million people (about the size of Virginia), has been over-represented on the awards podium at these competitions. According to researcher Stanislas Frenkiel, “With 144 medals since 1976 in both individual and relay races, a group of 19 athletes has won 45 percent of the medals taken by Switzerland in all categories of the summer Paralympic Games.”[10] Why, then, have Swiss para-athletes performed so well at these Games?

My own research reveals that while Switzerland ranks twentieth for total medals won in the Summer and Winter Paralympic Games since 1960, ranked by population Switzerland is sixth. At the Tokyo Paralympic Games 2020 (held in 2021), the Swiss delegation was made up of only twenty-one athletes, but it won fourteen medals. At age sixty-three, Heinz Frei won a medal in hand cycling, making him one of the oldest medalists in the competition. At a meet held in Switzerland in May 2022, both Marcel Hug and Catherine Debrunner set world records—Hug in the 1,500m and Debrunner in the 100m, 200m, 400m, and 800m. Manuela Schär set the world record in the marathon in 2019. In April 2023, Hug broke his own course record by winning a sixth Boston Marathon. Six days later, Hug won the London Marathon for the third time, again breaking his own record.

My inquiry is motivated by two friends of mine who became paraplegic hand cyclists, as well as a need to understand what motivates athletes who persevere despite suffering debilitating injuries. What I found was that disabled athletes and those free of disability share far more in common than they have differences. To design cities that better accommodate disabled people, urban planners would do well to emulate the Swiss Paraplegic Centre in Notwill, Switzerland, an hour-and-a-half train ride from Zürich.

Why focus on Switzerland? For one, there is compelling social media. In 2019, the YouTube video, “I am Manuela,” showcased the Swiss wheelchair racer Manuela Schär, who has won every World Marathon Majors competition, owns multiple Olympic medals, and currently holds the women’s wheelchair marathon world record. Schär has used a wheelchair since she was eight, when a playground accident paralyzed her from the waist down. Now in her thirties, how did she get so good, and are there others like her in Switzerland who are equally as dominant in their sport?

The Swiss Paraplegic Centre: A Model for Success

I spent a week investigating this question in the summer of 2022 at the Swiss Paraplegic Centre (SPC) in the small town of Nottwil, in Canton Lucerne, where I met athletes and toured the impressive facility. Established in 1990 by Dr. Guido Zäch and the Swiss Paraplegic Foundation, the SPC is spread across several hectares and features training and competition facilities, a hospital, two hotels, an archive, and research and development divisions. The SPC is a “one-stop-shop” for people with spinal cord injuries who want to compete or simply rejoin mainstream society as productive, self-sufficient citizens.

As a result of this facility and a nationwide supportive culture, I found that Switzerland is a nucleus for disabled athleticism. Unlike in the United States, where centers for disabled athletes are dispersed across the country, the Swiss training facility is centralized. Swiss athletes like Schär and Hug are part of a Swiss system that includes numerous other wheelchair athletes, such as Heinz Frei and Catherine Debrunner, all world record holders and winners of multiple Paralympic medals. It became obvious that their connection to the Swiss Paraplegic Centre is fundamental to these athletes’ success.

I was fortunate to connect with two para-athletes in Switzerland. One, Philipp Handler, is a three-time Paralympian. In Tokyo in 2021, he placed seventh in the 100-meter dash final. Visually impaired since birth, Handler competed in the 2012, 2016, and 2020 Paralympic Games in the T13 category. At the Tokyo Paralympic Games, he was the flag bearer for the Swiss team.

By day, Handler works at an insurance company to fund his life outside of training (he has an MA in finance). But life as a track athlete “allows me to actively challenge my limits,” he says. Growing up, he felt discriminated against by other kids. “My ambition was to be as independent as possible.”[11] Handler won a bronze medal at the World Para Athletics European Championships in June 2021. With a personal best time of 10.89, Handler is among the best in the world.

Another athlete I befriended was Tim Shelton, a Peer Counselor at the SPC facility in Nottwil. An Oklahoma native and one-time wrestler in high school who lettered in four sports (wrestling, football, pole vault, and baseball), Shelton was formerly a 6’1”, 191-lb. Marine in the special forces. In 1988, he was injured in North Carolina on a noncombat exercise. He has been in a chair for the past thirty-four years.

At the SPC, Shelton plays wheelchair rugby, one of the roughest sports in Paralympic competition. Part demolition derby, it consists of blocking, high-arcing throws, hairpin turns, and speed. In addition to basic skills like throwing and catching, players need to be able to plan and execute a play, all while an opponent is trying to ram them with their chair. Shelton’s competition chair is like a fortified tank. It is no wonder that wheelchair rugby is often referred to as “Murder Ball,” or “chess with violence,” as Shelton calls it.[12] The other wheelchair team sport is basketball, where the hoops are the standard ten feet, but there is little physical contact.

As a peer counselor, Shelton gives people the opportunity to ask questions and exchange information. Equipped with excellent multi-lingual skill that is required in Switzerland, he trains hotel workers, students, operating room attendants, nurses, and others. He also provides one-on-one coaching with patients and works with a nurse and occupational therapist. Once a month, patients are given the opportunity to get out and “see the real world,” such as a sunset cruise on Lake Lucerne.

Shelton showed me his rugby chair and allowed me to sit in it and wheel around the empty gym. He bounced the ball to me and it wedged under my wheel on my first try, stalling my chair cold. Eventually, I figured out how to sit the ball on my lap and wheel around, fearful that my hands would get injured just pushing the chair (players wear gloves). Yet, this is what Shelton has been doing for the past two decades. It is an excellent distraction from the injuries people have sustained. What they lack in leg or trunk ability, they make up for in upper body strength, quick, strategic thinking, and mental fortitude.

The sprawling SPC facility features 184 beds in eight wards, two intensive care units, two operating rooms, two outpatient rooms, forty types of therapy, and an education program called ParaWerk. The athletic facilities include a swimming pool, two full-sized basketball courts, a weight room, a sport medicine evaluation center, a nine-lane Mondo track with a laser timing system that rivals any of the major professional track stadiums in Zurich or Lausanne, and a specialized indoor training room, where elite athletes can train on rollers.

SPC supports a wheelchair adaptation center lined with every type of wheelchair imaginable, buzzing with workers fixing and adapting wheelchairs. The other side of campus features a workshop to adapt about three hundred cars per year for handicapped driving. In fact, all newly admitted patients are urged to obtain their driving privileges so as to assure their future mobility. If that is not enough, there are two hotels on site with 180 rooms, a library, and a full-service restaurant, all wheelchair accessible, of course. The entire facility is self-supported, open to the public, and is a ten-minute walk to the train station.

The SPC has been successful in getting injured people back into society. According to Shelton, 60 percent of the people in rehabilitation obtain employment before they leave the hospital. Most paraplegics spend an average of four to six months in the hospital, but some quadriplegics spend between nine and thirteen months. The hospital currently supports about eighty to eighty-five rehab patients (177 beds were occupied at the time of my visit). The center receives about 260 people per year, or about five per week, who come in with spinal cord injuries.

The facility is laid out in an extraordinary campus in the small town of Nottwil. Located on the shore of Lake Sempach, the area is replete with recreational amenities, as well. Easy to reach by train, all buildings are fully accessible and open to the public. The SPC’s proximity to Lucerne (about twenty-five minutes by train) and Zürich are important considerations for people with limited mobility. One of the features of the SPC is to return people who have suffered from a spinal injury to productive, normal life as quickly and completely as possible. In addition to skills training on how to maneuver in a wheelchair, the facility also adapts cars for people with wheelchairs. The facility adapts about three hundred cars per year for patients.

When asked about the accessibility of Switzerland, Shelton explains that even Switzerland falls short. There is no country-wide law for accessibility, like the ADA in the United States. Most restaurants do not have accessible bathrooms. Few hotels are adapted for people with disabilities, and those which are accessible are very expensive. Aside from the cars modified at the SPC, few cars are wheelchair adapted. Even new train cars designed to be more wheelchair accessible have the bathroom in the center of the car, separated by steps, while wheelchairs have to enter on either end. “There is not enough political advocacy for disabled people,” Shelton remarked (the Swiss Disability And Development Consortium only formed in 2016). However, Shelton is unwilling to be a more vocal advocate because he does not want to compromise the mission of the center or jeopardize foundation funding.

The longevity of spinal cord injury survivors is perhaps the greatest success of the center. In 1988, when Shelton sustained his injury, he was told he would live to be “about forty.” Now, at age “fifty-four and a half,” he is living proof that SCI survivors can live a long life and thrive. Also, chairs have changed. The first chairs were heavy steel; now they are made out of titanium and are longer lasting. Shelton estimates that he has worn out seven chairs in four years. “I don’t have limitations,” he exclaims. Perception has changed a lot. Now, more people in wheelchairs are living and moving around on their own. Shelton and the SPC reinforce the notion that wheelchair accessibility is good for everyone.

Swiss Para-Athletic Success: “It’s not just the building”

Part of the success of disabled Swiss athletes is attributable to the country’s military infrastructure. Military service is mandatory for every Swiss citizen. Those injured in the line of duty are cared for as part of the country’s national health care system. In addition, the Swiss army has incorporated athletics, including disabled sports, into its ranks since 2021. Roger Getzmann, the Department Head of Wheelchair Sports Switzerland, explains that “Switzerland’s sport system is strong, despite being a small country.” He says, “It’s not just the building [at SPC]. It’s the supportive mentality and support system and coaching.”[13] As of 2022, 140 athletes can train for their sport while in the Swiss army; only three or four are top-level para-athletes, and not just in wheelchair athletics.

It is clear that the Swiss Association of Paraplegics coupled with the Swiss Paraplegic Center in Nottwil and the International Paralympic Committee have done an outstanding job of changing perceptions about the abilities of paraplegics. But everyone with whom I spoke agreed that more progress can be made. According to Shelton, “wheelchair accessibility is good for everyone.” But it is harder to adapt older spaces than to plan accessibility from the beginning, especially in a country like Switzerland, which has its share of old buildings. Sometimes, even the most well-intentioned construction falls short. “Every architect should spend a week in a wheelchair,” Shelton suggests. “Time is needed to continue to change perceptions,” Getzmann says. “TV coverage is good, but more planning is needed. We try to provide a positive experience. The [International Olympic Committee] brought Paralympics more visibility and made the sport more competitive. This helps change public perceptions.”

Some elements of the Swiss model facility, training regimen, and coaching system have been copied by other countries, but few support all components in one place. In the United States, for instance, specialized facilities and expert coaches exist, but they are dispersed around the country. As a center for parasports, Nottwil is so influential that many athletes, such as Schär, moved to that canton to be close to the SPC facility. From the impressive facility in Nottwil, the Swiss Paraplegic Centre routinely produces world record holders and top athletes in various disabled sports, especially wheelchair track and road competitions. But thanks to mandatory military service and a nationalized health care system, famous names like Manuela Schär and Marcel “the Silver Bullet” Hug are part of a larger Swiss infrastructure that encourages excellence in Paralympic sports. Though Switzerland has been slower to adapt its cities to the needs of disabled people than the United States, efforts to make the country friendlier to people with disabilities has often been led by high profile award-winning and record-setting athletes. It appears that, for the foreseeable future, Switzerland is likely to remain near the top of Paralympic competition.

Dan Holland is an adjunct professor of history at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A Pittsburgh native, Dan founded the Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh and has held leadership positions at local, regional, and national community reinvestment organizations. He specializes in American history, history of Pittsburgh, nonprofit management, historic preservation, and community reinvestment. Dan authored numerous studies on financial institution lending in Pittsburgh as well as others regarding African American history in Pittsburgh, historic preservation, and the impact of mid-century urban renewal upon minority communities. His latest publication is a book chapter entitled, “Narratives of Resistance in Lyon and Pittsburgh,” in Constructing Narratives for City Governance, published in Cheltenham, United Kingdom, by Edward Elgar Publishing (2022).

Featured image (at top): Pictogram for Athletics of the Olympics and Paralympics 2008, WikimediaCommons.

[1] One supporter of the Paralympics, Justin Dart Jr., who used a wheelchair himself, became a driving force behind the ADA. See David Davis, Wheels of Courage: How Paralyzed Veterans from World War II Invented Wheelchair Sports, Fought for Disability Rights, and Inspired a Nation (New York: Center Street, 2020), 317-320.

[2] “Majority of Car-Pedestrian Deaths Happen to Those in Wheelchairs, Often at Intersections,” Georgetown University Medical Center, Nov. 19, 2015, https://gumc.georgetown.edu/news-release/majority-of-car-pedestrian-deaths-happen-to-those-in-wheelchairs-often-at-intersections/. John D Kraemer and Connor S. Benton, “Disparities in Road Crash Mortality among Pedestrians Using Wheelchairs in the USA: Results of a Capture–Recapture Analysis,” BMJ Open 2015, https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/5/11./e008396.full.pdf.

[3] Jere Longman, “New York City Marathon; Proceeding With Caution,” New York Times, Nov. 7, 1995, https://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/07/sports/new-york-city-marathon-proceeding-with-caution.html.

[4] “World-Class Wheelchair Athlete Hit by Car in DUI Hit-And-Run,” Morgan & Morgan, Nov. 3, 2011, https://www.forthepeople.com/blog/world-class-wheelchair-athlete-hit-car-dui-hit-and-run/.

[5] Chris Hatler, “Paralympic Gold Medalist Is Hit by a Driver, and Pulls Out of Boston Marathon,” Runners World, Sept. 20, 2021, https://www.runnersworld.com/news/a37669058/susannah-scaroni-hit-by-driver/.

[6] “Paralympian hit by self-driving car inside athletes’ village,” Asahi Shimbun, Aug. 27, 2021, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14427620.

[7] Davis, Wheels of Courage, 321.

[8] Davis, Wheels of Courage, 284.

[9] Davis, Wheels of Courage, 287.

[10] Stanislas Frenkiel, “The Development of Swiss Wheelchair Athletics. The Key Role of the Swiss Association of Paraplegics (1982-2015),” Sport in Society 21, no. 4 (Apr. 2018).

[11] Author’s interview with Philipp Handler, July 14, 2022, Zürich, Switzerland.

[12] Author’s interview with Tim Shelton, July 11, 2022, Nottwil, Switzerland.

[13] Author’s interview with Roger Getzmann, July 12, 2022, Nottwil, Switzerland.