Our fourth author in the 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest, Allie Goodman, describes the experience of a young woman and her family “stumbling through” efforts to obtain assistance provided by a settlement house but subject to conditions, including surveillance and extralegal work agreements. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here.

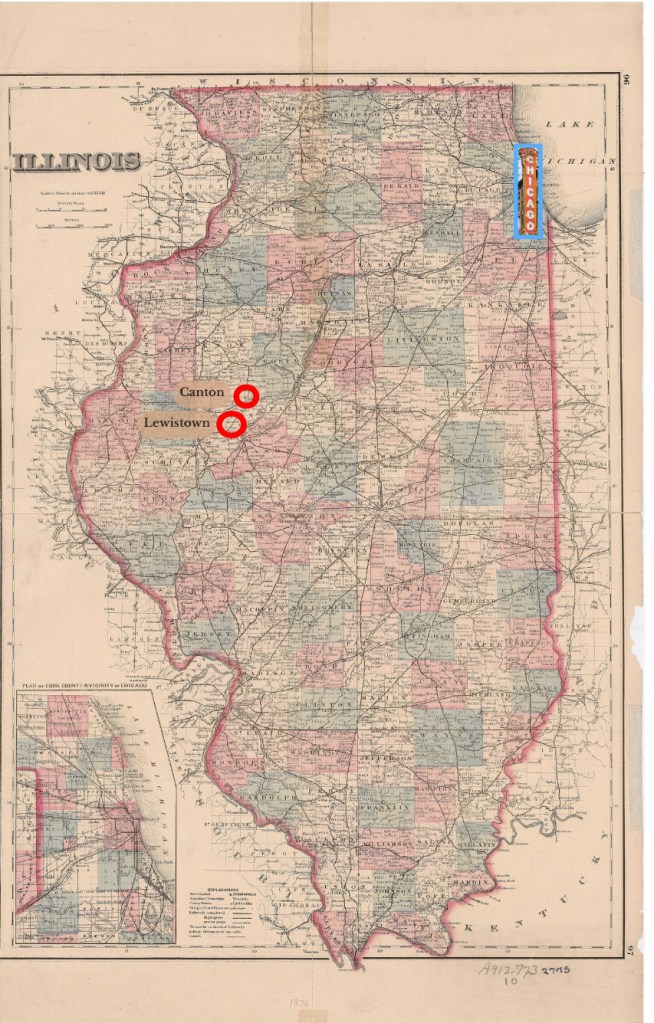

One evening in late August 1914, Mae Neiwski sat by Lake Chautauqua listening to a young woman read Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm to a captivated audience.[1] The Fulton County fair in Lewistown, Illinois, boasted many entertainments, from readings to lectures to music, which Mae enjoyed with “a very nice group of young folks” whose behavior her employer, Mrs. Lucy Rowan, described as “jolly, happy, lots of fun, but nothing to cause comment.”[2] Rowan hoped this cohort’s behavior might show Mae the bliss of contentment with country life, if she would only succumb to it. Mae did walk away a changed girl. But it was the reading rather than the cohort that stirred her spirit.

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm is a 1903 novel by Kate Douglas Wiggin about a young girl sent away to help provide for her family.[3] It is part of a genre of “girl books” conveying messages of uplift through gumption, industriousness, charm, education, and amiability. In the novel, Rebecca used these qualities to secure a job offer as a teacher. When Mae read Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm that August, she likely discovered a kinship with the protagonist. She had lived in the small farming town of Canton, Illinois, for nearly a year—a stark cultural and geographic change, at nearly two hundred miles southwest of her beloved hometown, Chicago. Like Rebecca, she struggled with her new environment and employer. Both Rebecca and Mae were about fifteen and both hoped to achieve independence through wage-earning—a dream Rebecca ultimately found unnecessary.[4] In the end, Rebecca’s mother was injured, forcing her to turn down the teaching job and move home. She provided for her family with inheritance from her late aunt and an incredible stroke of good luck—a railroad purchased her family’s farm. Luck and inheritance rather than industriousness were Rebecca’s salvation. Now Mae simply needed an inheritance and a stroke of good fortune to complete the arc.

Mae found neither inheritance nor good luck. Even her ability to achieve independence through wage earning was limited by, perhaps ironically, the employment arrangement that her mother, the settlement, and her employers collaborated to create.

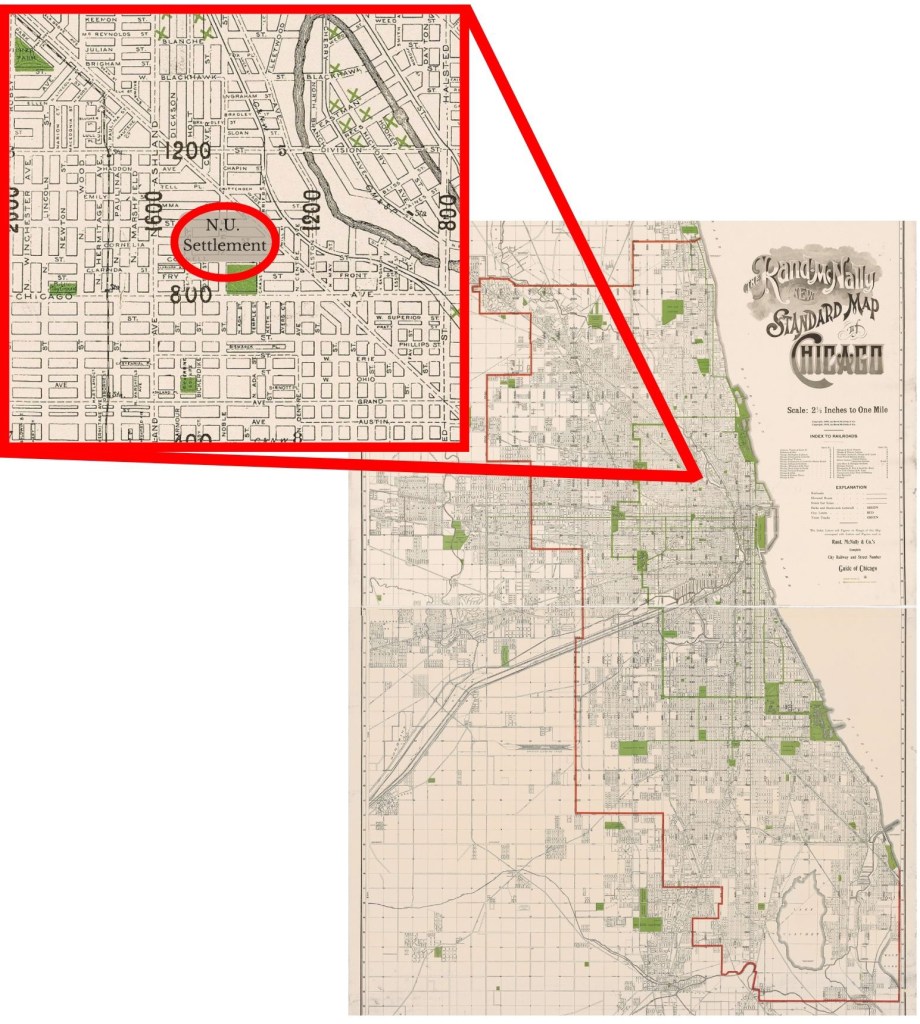

Mae’s story is one of expectations unfulfilled. Mae likely hoped to mirror Rebecca’s story. But because Mae did not receive any great stroke of fortune, she forged her own path to provide for her family. Harriet Vittum, head resident of Northwestern University Settlement, hoped that sending Mae to rural Canton might provide the right kind of work under the right sort of influences while deterring her from Chicago’s corrupting entertainments, though Mae’s determination to return to Chicago overwhelmed these aspirations.[5] And it is a story of a woman and a girl at odds, stumbling through the unintended trouble wrought by an extralegal arrangement forged in the burgeoning family policing system.

Mae’s arrangement was not particularly unique. Nor was familial collaboration with settlement agents or the unintended outcomes of such arrangements. Missionaries, activists, and social service workers forged the settlement movement to provide services such as healthcare, clean milk, daycare, and recreational activities for youth and families.[6] Yet classism, racism, and xenophobia bounded the types of services that settlements offered and, more broadly, the type of reform settlement agents helped craft at the municipal and state levels.[7]

Settlements were not merely locations of social service, but locations that spurred the creation and enforcement of law. Settlement workers understood themselves as an operating service that connected families to charitable organizations. Stories from youth like Mae and their families show that many sought settlement assistance because they hoped to use their services to sidestep involvement in the criminal and juvenile legal systems. Some agents only volunteered at the settlements, while others both lived and worked at the settlement as “residents,” “visitors,” and “neighbors.” Armed with these seemingly benign—even positive—monikers, agents encroached into the intimate while erecting club participation as a barrier to access services.[8] With the support of police and judges, agents enforced ostensibly voluntary arrangements through threat of state intervention. In some cases—such as Mae’s—this included family separation.[9] In practice, many families found that settlement involvement opened them up to even more surveillance, policing, and criminalization, but without even the meager protections that formal legal intervention might have offered.

Harriet Vittum collaborated with Mae’s sick mother in 1913 to create a quasi-adoptive employment arrangement. Mae would learn domestic service work, provide for her family, and eschew notorious entertainments. Her mother would collect checks at the settlement after attending parenting classes. Arrangements like Mae’s closely mirrored binding out arrangements, wherein judges sent youth from municipal institutions to live with families on farms. Binding out was criticized in its own time for its lack of oversight and well-documented abuses.[10] But Vittum and her compatriots expected their case management approach to eliminate the abuses found in the traditional binding out system because it was rooted in personal relationships with trusted partners. In this case, Vittum entrusted her childhood friend, Lucy Rowan, with Mae’s care. For her part, Rowan promised a good home, with access to good, fresh air, in a good family—plus a small salary—in exchange for domestic labor.[11] By Thanksgiving 1913, Mae was on a farm in Canton.[12]

While in Canton, Mae was convinced by Rowan to send part of her paycheck home; Mae spent the remainder on local entertainments.[13] Rowan took careful note of how Mae spent—and largely saved—her earned wages. She spent some money on photos of herself, which she likely sent to a boy from Chicago who she was in communication with. “Her other expenditures are few and things she really needs. She is saving her money for her clothes this spring, and she shows more and more judgment in her choice of things for herself.”[14] As Mae saved money, she kept in touch with both family and friends from Chicago, all while reporting her successful transition to Vittum. But Mae never felt at home in Canton. As early as February 1914, Rowan reported Mae’s correspondence with this boy to the settlement. Rowan feared that the lure of romance would draw Mae back to Chicago. And Mae did hope to return home, but because she felt Rowan treated her cruelly rather than any grand romance. In June 1914, Mae wrote to her brother saying:

“I wanted to hear what Ma said about coming home. I am coming anyway because I can’t stand it out hear[sic] anymore they just scold me for everything and Mrs. [Rowan] gets a spell sometimes and she won’t even talk to me so I guess I won’t stay any longer I’ll get me a job for 8 or 9 dollars and then I can give Ma more to come I know she needs it…I had all I wanted from them since Easter ofcaurse[sic] Ma don’t realize it because she don’t have anybody giving her cross looks or anything but I do—and I can’t stand it from strangers.”[15]

Mae’s five letters to Vittum used intentional cursive and mindful phrasing. This sixth letter alone contained scrawled, nearly frantic writing. She was no longer performing propriety to the person ultimately in charge of her freedom. She was venting her dissatisfaction to a family member who she hoped could aid her escape. But Vittum got the letter.[16] Vittum responded by shaming Mae for expressing dissatisfaction. She reminded her of her mother’s poor health, how hard her mother worked, how good her life was in Canton, and all the doors that this opportunity might open for her. Vittum concluded the letter with a candid threat:

“If you should give up all these nice things and come back to this dirty old part of Chicago and stay out nights as you were doing and spend your time the way some of the girls spend theirs, there is only one thing we can do, and that is take you to the Juvenile Court. And I am sure Judge Bartleme would be pretty severe to a girl who would do what you say you are going to do. Now don’t come home until you have thought it over very carefully and decide which is the nicer place—the [Rowan] farm near Canton or the place Miss Bartleme would have to send you. Be a woman, [Mae], and prove to your mother that you appreciate all her hard work, and her suffering.”[17]

While this threat reflected a cocktail of both reality and fictionalized panic, it nonetheless had a chilling effect on Mae’s correspondence.

Two months later, Mae went to the fair in Lewistown and heard the reading of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm. Mae received this story—about a girl beating all odds to return home with the means to support her family—at a pivotal moment in her life. She finally wrote to Vittum, saying she thought the book was “grand” and hoped to find new work with a family in Evanston.[18] Vittum again assumed that romance rather than better work close to family fed her desire and warned Mae that her beau had lost his job and kept poor company. Besides, Vittum argued, there was no work in Chicago and “girls just like you are hanging around the street corners without work and without money to buy clothes or food. You do not know how lucky you are.”[19]

Reformers like Vittum hoped arrangements like Mae’s could save youth from vice.[20] But these hopes were not borne out. In practice, blurring the lines between employee and boarder facilitated quiet servitude, and the informality of Mae’s arrangement bound her into service without mechanisms of appeal. Vittum and Rowan’s personal relationship left Mae without an advocate. When Mae attempted to advocate for herself, she faced threats of legal retribution. Even without prejudiced relationships, a train could only take visitors part of the two-hundred-mile journey from Chicago to Canton, rendering regular visits and personal oversight largely impossible. The settlement’s ties to formal legal institutions, such as the Juvenile Court, and formal legal actors, such as Judge Bartleme, gave weight to Vittum’s threats, pressing Mae into service by both the informal and formal particularities of a new system that was defining itself as it was defining deviance.[21] This forced Mae to rely on discourse of contentment and self-betterment—of niceness—to avoid the most coercive and formal aspects of the juvenile legal system, while quietly planning her homecoming.[22]

Mae returned to Chicago in the Fall of 1914—settlement threats be damned. And…nothing. Her family’s file essentially quieted, except for several mentions of Christmas baskets and updated addresses. Mae married two years later, in September 1916. We do not know if she married the boy she wrote to while in Canton—or indeed, if she even wrote to any boys, because Mae herself never confirmed this correspondence—but the timing suggests she met someone else. Ultimately, Vittum never followed through on her threats to refer her case to the Juvenile Court. Her case shows that while settlement agents used legal threats to compel compliance with agreements, their actual authority to do so was built on a foundation of sand and crumbled with the daring challenge—or gumption—of an adolescent girl.

But settlement involvement nonetheless shaped Mae’s adolescence and adulthood by forcing her to navigate and contend with boundaries of propriety which she may not have personally identified with. And Mae was not alone. Her case is but one example of the many children and youth left to navigate the tightrope of hardening family policing systems in order to meet tangible, immediate needs.[23] While cultural touchstones such as Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm allowed girls like Mae to escape into fantasies of independence, the social and legal realities of Progressive Chicago ultimately bound youth into service with little recourse.[24]

Allie Goodman is a PhD candidate in the history department at the University of Michigan. Her work centers histories of family policing, childhood and youth, the carceral state, and legal history. She is currently working on a dissertation about childhood and youth experiences with Chicago’s Progressive Era juvenile legal system.

Featured image (at top): “Garden Scene” from Illinois State Training School for Girls, Superintendent of Public Instruction, “Geneva Girls School,” Record Series 106.25, Illinois State Archives

[1] Per an agreement with the archive and to maintain the privacy of those people who were involved with the settlement, all names from casefiles have been changed, except for settlement workers and police officers, whose names are in the public record. Footnotes will likewise omit names.

[2] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[3] Kate Douglas Wiggin, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, (Boston/New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, The Riverside Press, 1903).

[4] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[5] Settlement houses were typically opened in densely populated urban areas and run by reform-minded wealthy and middle-class people—largely women, many of them recent graduates from prestigious institutions such as Northwestern. Northwestern University Settlement, for example, opened above a feed store in West Town on Division Street in 1892, but by 1901 it had moved to its own space at 1400 W. Augusta, where the settlement remains today. At the time, the area was largely Polish Catholic and poor and working class, reflecting the most common demographic accessing settlement services. Mary E. Odem, Delinquent Daughters: Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 95.

[6] See, for example, Kyle E. Ciani, Choosing to Care: A Century of Childcare and Social Reform in San Diego, 1850-1950 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019); Joanne L. Goodwin, Gender and the Politics of Welfare Reform: Mothers’ Pensions in Chicago, 1911-1929 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); See also Wendy Rouse Jorae, The Children of Chinatown: Growing Up Chinese American in San Francisco, 1850-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

[7] This is particularly true with respect to means-testing. See, for instance, Wendy Rouse Jorae, The Children of Chinatown: Growing Up Chinese American in San Francisco, 1850-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009). Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York/London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016); Sarah Haley, No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Books, 2016); Crystal N. Feimster, Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009); Geoff K. Ward, The Black Child-Savers: Racial Democracy and Juvenile Justice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012).

[8] See also Wendy Rouse Jorae, The Children of Chinatown. Uneasy alliances with community-members—for Rouse Jorae between missionary workers in San Francisco’s Chinatown and in this case, between Settlement workers—provided critical services, but at a steep cost. These quiet morality tests included participation in the Mothers Club, English classes, and Home Culture Club.

[9] Reformers created uneasy relationships with communities, which allowed them to lobby local, state, and even federal agencies to “save the children” as subject-matter experts. International Save the Children Fund pamphlet, Box 70, Folder 1, “Edith and Grace Abbott Papers,” University of Chicago Special Collections, University of Chicago. The second bullet of Declaration of Geneva, signed by the General Committee of the Save the Children International Union on February 28, 1924, which was later approved by the League of Nations, read, “The child that is hungry must be fed; the child that is sick must be nursed; the child that is backward must be helped; the delinquent child must be reclaimed; and the orphan and the waif must be sheltered and succored.” Reformers viewed delinquency as an individuated but widespread disease that, with proper individualistic attention might be cured. Reform-minded settlement agents worked on committees, commissioned studies, and many even shaped policy without ever winning an election. See, for example, Grace Abbott’s speech before the Annual Convention of the American National Red Cross, April 14, 1913, titled, “The Challenge in Child Welfare.” Their peripheral experiences with the “poor” and “downtrodden”—paternalistic verbiage reformers frequently wielded to describe those they hoped to serve—were heralded as “first hand” accounts in pamphlets such as Louise De Koven Bowen’s “The Straight Girl on the Crooked Path: A True Story.” When crafting policy, building prisons and jails, reviewing annual reports, forming boards of administration, and creating governance with practical implications on family aid, state and local government officials—including Governor Lowden—called on these reformers so-called “first-hand accounts” rather than those trodding across the “worn doorstep” of settlements to access these services. There was therefore a disconnect between those accessing aid and those creating policy about how to access aid. See also Odem, Delinquent Daughters.

[10] Megan Birk, Fostering on the Farm: Child Placement in the Rural Midwest (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

[11] In Crescent City Girls, LaKisha Simmons writes that many young girls used niceness to emphasize respectability within and outside of the “striving class”: “Niceness in this context referred not only to proper behavior but also to high standards of cleanliness and the properness of the home.” LaKisha Michelle Simmons, Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press Books, 2015), 4, 125.

[12] We do not know the precise details about the genesis of this arrangement. A letter to Vittum on April 5, 1914, provides an important clue as to how such arrangements worked, if not this one specifically. Rowan wrote: “If you have already promised a girl a place down here or have one you want to come, I think I could get her a place in a nice family near us.” This type of communication reveals the informality of these arrangements. Settlement agents worked with people they knew—with friends and with friends of friends—to create and maintain a network of placements for children like Mae, who they felt could benefit from fresh country air, a room with a “nice” family, work, and a salary, without the city temptations of the nickelodeon, theater, or dance hall.

[13] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[14] This could just as easily be a commentary on the ways in which spending habits change with age rather than a referendum on Rowan’s wise teachings.

[15] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[16] We do not know the chain of custody. It is entirely possible her brother gave it to her mother, who then turned it over to Vittum, or that her mother found the letter herself.

[17] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[18] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[19] Series 41/2, box 2, case 685, Northwestern University Settlement Association Records Case Files, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

[20] Within the context of increasing panic over so-called “white slavery” and the “moral dangers of wage-work,” Progressives feared that young, working-class women and girls might easily be lured to evening commercial amusements such as dance halls, amusement parks, and movie theaters. “Such entertainments, reformers charged, exploited youths’ need for play and encouraged illicit behavior. They considered the public dance hall, in particular, ‘a source of evil.’” Odem, Delinquent Daughters, 104. In some ways tied to complicated fears over wage-work—daughters like Mae should help support their families, but through the right kinds of work—Progressive panic about a spectrum of sex work stemmed also from expanded criminalization in rapidly-growing urban centers. By regulating sexual labor, cities capably segregated vice districts, typically pushing red light districts into predominantly Black neighborhoods and then criminalizing those neighborhoods because of the manufactured preponderance of vice. In Chicago, for example, this manufactured crisis justified a catastrophic police raid of the Levee district in 1912. At the same time, reformers pressed a panic over so-called white slavery fueled by a desire to “save” those afflicted white girls. This created double standards for sexual propriety in terms of race, class, and gender. “The sexual double standard, articulated in Victorian terms, allowed men sexual access to women of their own class and to classes (and races) below them on the social hierarchy yet insisted on absolute chastity in women.” In Progressive terms, those women and girls who violated a particularly broad set of standards, which came to include enjoying urban amusements, “fell outside of the bounds of respectability and often forfeited legal and, possibly, familial protection.” Jessica R. Pliley, Policing Sexuality: The Mann Act and the Making of the FBI (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 11-13.

[21] According to historian Michael Willrich, “Every phase of progressive court reform raised problems of institutional capacity in an age of deep suspicion of public spending and patronage. The problems were often resolved by associational arrangements between the state and civil society.” Probation officers, for example, volunteered in this role and were also police officers or charitable workers—some, like Harriet Vittum, even worked at Northwestern University Settlement and at Hull House. Another example was the Juvenile Protective Association. In 1909, a group of women, many of whom were instrumental in creating the Bar Association Bill and, ultimately, Chicago’s Juvenile Court—and its network of probation officers—created the JPA to curtail youth arrests through direct intervention. This was a non-state police force that investigated vice and issued salacious reports meant to garner public support for anti-vice legislation. Willrich notes that such reports “were not just moralistic screeds; they were well-documented sociological briefs replete with specific recommendations for legal reform.” Though, as Miroslava Chavez-Garcia writes, the subjectivities, training, and specific goals of sociological studies influenced methods and analysis and therefore the findings of such work. Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, States of Delinquency: Race and Science in the Making of California’s Juvenile Justice System (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 85; Michael Willrich, City of Courts: Socializing Justice in Progressive Era Chicago (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 135.

[22] For more on “niceness” and performing respectability, see Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: NYU Press, 2011); LaKisha Michelle Simmons, Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 124.

[23] For definitions of “family policing” versus “child welfare,” see Dorothy E. Roberts, Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families—And How Abolition Can Build a Safer World, (New York: Basic Books, 2022).

[24] Even as her wealthier counterparts designed arrangements for themselves—which sometimes included living and working at settlements—to maintain independence, against contemporaneous norms. It is noteworthy that even as settlement agents pressed middle class morality on poor and working-class neighbors whose economic realities made achieving these standards undesirable, they did not hold their own daughters to the same standards.