The third entry in our 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest is by Julie Haltom. She writes about the myriad of stumbling blocks faced by mid-twentieth-century homesteaders in Southern California’s deserts, and the short- and long-term ramifications of the Bureau of Land Management’s Small Tract Lease program. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here.

Between 1938 and 1976, tens of thousands of urban Southern Californians became rural landowners by applying for public land.[1] People like Melissa Stedman, who began leasing her parcel in 1941, succumbed to an ongoing “land fever” that only escalated in the years to come. As Stedman described it, the desire for land during this period was so strong that a “horde” of claimants “swooped down” on federal land offices in a “mad rush.”[2] Few of these individuals had lived in a rural setting before grabbing their hammers, pickaxes, and shovels; in fact, most hailed from Los Angeles County. But these urban pioneers did not let their inexperience stop them. Eager to own land and use it as an escape from the city, they flocked to the Mojave Desert, the hottest and most inhospitable part of the state.

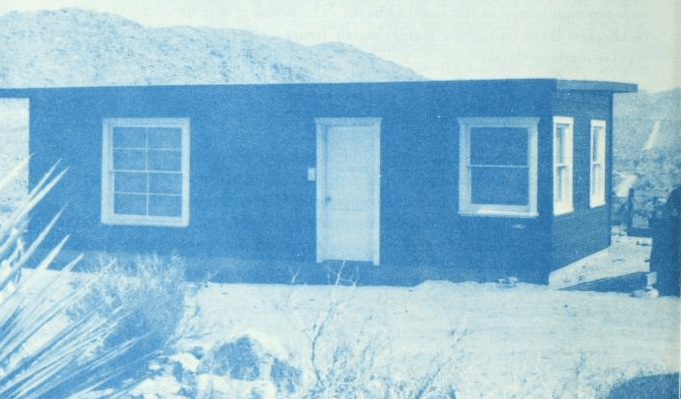

They obtained their land under a little-known revamp of the 1862 Homestead Act. Passed in June of 1938 and dubbed the Small Tract Act, this legislation allowed the General Land Office—and later, the Bureau of Land Management—to dispose of unused federal land in five-acre parcels.[3] Like the original Homestead Act, which lured four million Americans into the West by offering land on the cheap, the Small Tract Act’s purchasing scheme was lease-to-own with nominal fees. Lessees earned their land patents by completing mandated improvements within a set period of time, a process informally known as “proving up.” At the outset, this referred to a dwelling worth $300 in materials built within five years, although the terms changed several times over the course of the program.[4]

In Southern California, most of these five-acre parcels were in the Mojave Desert, with hotspots in Twentynine Palms, the Morongo Valley, and Barstow. Locals began calling them “jackrabbit” homesteads. Over the years, interest in these desert tracts only increased. By the 1950s, homestead hopefuls, who were predominately white and middle-class, were demanding land faster than the Bureau of Land Management could process applications.[5]

Hot, dry, and isolated, the Mojave Desert proved tough to tame. Most areas lacked water, utilities, and roads and encompassed rugged terrain. Some applicants trekked out to the desert to view the land on offer, but many chose their parcels off a map, sight-unseen, only to be so disappointed that they reapplied.[6] Stedman described one homestead location she rejected as “a sandy wash, infested with lizards, beetles and every manner of thing that creeps or crawls” and another as “a boulder-strewn arroyo where there wasn’t enough level ground for a pigeon roost.”[7] Homesteader Tommy Tomson’s experience shows that the Mojave Desert was also troubled by extreme weather. Just weeks after he finished his cabin, a freak windstorm ripped it off its foundation and tossed it into a ravine.[8]

Still, these urbanites grappled with the process of proving up—building cabins, digging cisterns, hauling water, beating roads and trails into the sand and scrub. Trial and error guided them through the desert and—like Stedman did when she converted a sewer-pipe to a chimney—they repurposed available materials to suit their needs.[9] As they toiled, they joked about the Mojave Desert’s frontier feeling. “[A] desert homestead is not for the timid or hothouse grown individual,” Stedman quipped, but rather those who possessed a good deal of “hardihood” and “resourcefulness.”[10]

Fellow jackrabbit homesteader Randall Henderson agreed with Stedman, noting that living in the Mojave Desert was “only for those with a bit of pioneering blood in their veins.” He specifically referred to “Americans who find infinite pleasure in doing the hard work necessary to provide living accommodations” in hostile places.[11] These views drew on enduring ideas about frontier spaces popularized in the nineteenth century. Prominent works by Frederick Jackson Turner and Theodore Roosevelt described the frontier as a return to the “primitive” that tested physical strength and mental resolve.[12]

For determined lessees, the potential benefits outweighed the hardships. If they managed to meet their lease requirements, they would become landowners. Historians have shown that Americans connected land to stability and economic opportunity from the earliest days of colonial settlement.[13] More importantly, that land would be desert land, which many homesteaders viewed as healthy, natural, and blissfully distant from the pollution and noise found in Los Angeles.

In believing that Southern California’s deserts held healing properties, jackrabbit homesteaders drew on ideas that dated back to the 1870s. Eager to increase tourism and permanent migration, local boosters issued reams of promotional material that touted “climate” cures for a variety of ailments. California: For Health, Pleasure, and Residence, a Book for Travellers and Settlers, published in 1873, implored Americans to “think of their own country” when weighing vacation destinations, as Southern California offered “so many delights…for the tourist, and so many attractions for the farmer or settler looking for a mild and healthful climate.”[14] Similar ideas persisted into the twentieth century. Physician James B. Luckie prescribed the “warm and sunny air” of Twentynine Palms to so many asthmatic World War I veterans that locals often credit him as one of the city’s founders.[15]

Henderson echoed these sentiments in 1946. In his mind, the Mojave Desert promised “health-giving sunshine” and “a breeze that bears no poison.” It was also one of the last places in the United States where “nature is still supreme.”[16] Urbanism as a threat to nature was a common theme in the works of Ralph Borsodi, who described industrial cities as crowded, noisy, and polluted and championed homesteading as beneficial to physical and mental health. In the jackrabbit homesteading period, many of Borsodi’s ideas resurfaced in homesteading how-to guides that encouraged urbanites to avail themselves of the fresh air and sunshine in rural spaces.[17]

Henderson’s jackrabbit homesteading brethren held similar views and often expressed them in anti-urban ways. Stedman admitted that her decision to file a land claim stemmed from a “back-to-the-land yearning,” and she described her homestead as a place with “earth underfoot and space to breathe.” Bill Moore, who began leasing a small tract in 1950, noted that living “away from city lights on our own piece of sand” offered his family a quiet respite from Los Angeles, which he described as “a land of frenzy.”[18]

Like Moore, Catherine Venn filed a land claim in 1950. Going in, she recognized that any parcel in the hot, sandy Mojave Desert would be difficult to prove up, but she believed that the “real value” of a desert tract rested with what it offered—an escape from the “speed and motion” of Los Angeles and the opportunity to live in an area with “nothing man-made.” She framed the latter as something she needed to enjoy while it lasted, as “soon enough mortar, bricks and lumber” would invade the desert’s “natural state.”[19] Ironically, Venn and her compatriots rarely acknowledged that their endeavors as homesteaders were hastening that “invasion.”

After several straight weeks on her homestead, Venn stopped using her alarm clock and started rising and retiring with the sun, a habit she insisted imbued her with new energy. She also claimed that simply living in the desert and away from the city had improved her overall health.[20] For homesteaders like Stedman, Henderson, Moore, and Venn, a rural life in the desert was the perfect antidote to urban ills.

If jackrabbit homesteaders struggled with the process of proving up, the Bureau of Land Management struggled as administrators. In 1957, the House of Representatives held a subcommittee hearing about the Small Tract Act. And while the hearing was intended to address concerns about overdevelopment and desert conservation, many of the jackrabbit homesteaders in attendance used it as an opportunity to air their grievances about the government. Some complained that the land offices did not have enough employees to meet the high demand for applications; others insisted that the Bureau of Land Management took too long to open new areas for small tract leases and to issue land patents. Still others felt that the rules regarding applications and lease were too complicated, leading to confusion and doubt.[21] Overall, these jackrabbit homesteaders believed that government mismanagement was interfering with their ability to enjoy the land they had struggled to improve into non-urban havens.

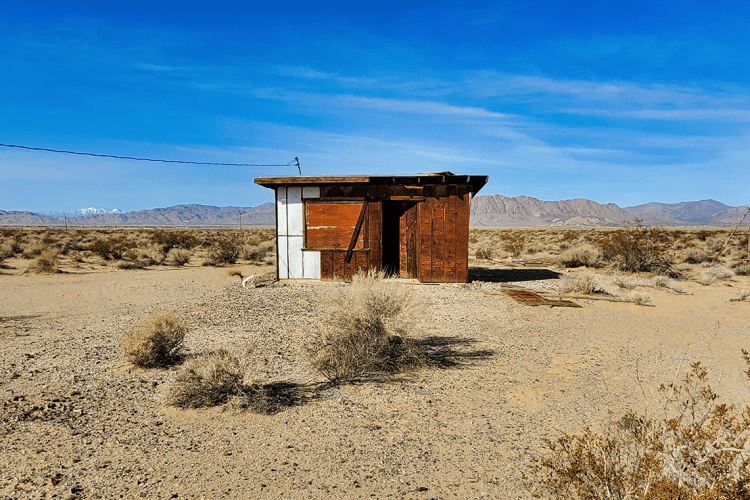

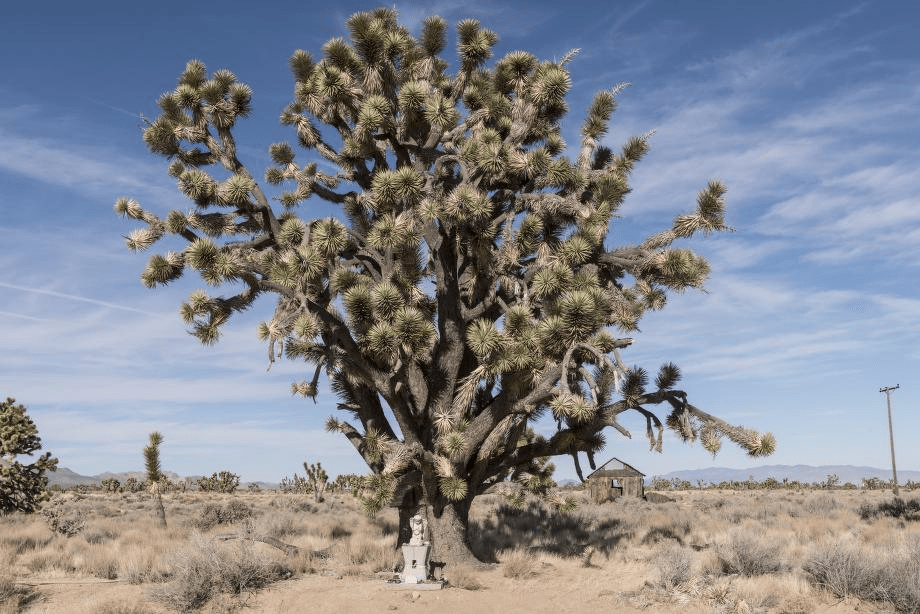

In 1976, the Bureau of Land Management ended homesteading in the continental United States. But by this point, jackrabbit homesteading had already fallen into decline. Over 72,000 applications were filed between 1938 and 1976, but only 27,881 were successfully proved up.[22] Isolated and lacking modern infrastructure, many who did prove up failed to make their parcels thrive. Most simply walked away. But their cabins remained, morphing into dilapidated eyesores as they bleached and withered in the desert sun. In 1999, San Bernardino County received a federal grant for a demolition effort dubbed “Shack Attack,” but for a variety of bureaucratic reasons, it was only partially successful.[23] Many of the cabins still stand today, visible to anyone who drives Highway 62 between Whitewater and Sheephole Valley Wilderness or heads north from Twentynine Palms on Amboy Road.

This legacy of abandoned shacks speaks to the environmental consequences of frenzied development. Throughout the world, rapid and poorly planned expansion into arid spaces has exacerbated issues like deforestation and desertification.[24] Nature’s return to the homesteaded areas of the Mojave Desert has been slow; the five-acre grids are still noticeable on satellite views, as are the footpaths homesteaders wore into the sand as they visited their neighbors.

Some, like the parcel Edward Wall homesteaded in the 1950s, are now for private sale.[25] Once bought and refurbished, old jackrabbit homesteads often end up on the short-term rental market, advertised on websites like Vrbo and Airbnb. The area around Joshua Tree has seen an explosion of short-term rentals since 2019; a recent article in the New York Times estimated the number at over 1,800. Residents complain that the influx has inflated the local housing market and encouraged raucous parties attended by outsiders who, while drunk, litter and trespass. They also fear that the constant flow of people poses a threat to the iconic and already endangered Joshua trees, forty percent of which are now growing on private land.[26]

In 1938, the Small Tract Act opened the Mojave Desert to a homesteading project that still impacts it to this day. Tens of thousands of city-dwellers took up rural living in an inhospitable place, then stumbled against the realities of desert landscapes and with the demands associated with leasing public land. Behind them, they left desolate and collapsing cabins, many of which have ushered in a new era of ownership that encourages the crowds and noise jackrabbit homesteaders sought to avoid.

Julie Haltom is a history graduate student at California State University, Long Beach. Her MA thesis examines small-tract homesteading in postwar Southern California within the contexts of frontier nostalgia, American conceptions of land ownership, the rural/urban divide, and the racialization of residential space. Her other research interests include the American frontier as a place, Westward expansion as a process, and representations of women and gender in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century United States. Previously, she acted as the Graduate Editorial Assistant for The History Teacher, a peer-reviewed academic journal focused on history education. She begins lecturing at California State University, Long Beach, in Fall 2023.

Featured image (at top): Edward Wall’s homesteading cabin. Photo courtesy DesertLand.com.

[1] “Public land” refers to “areas of land and water owed collectively by U.S. citizens and managed by government agencies.” The Wilderness Society, “What Do We Mean by Public Lands?” https://www.wilderness.org/sites/default/files/media/file/Module%201%20-%20Reading.pdf.

[2] Melissa Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” Desert Magazine, December 1945, 13.

[3] President Harry S. Truman formed the Bureau of Land Management in 1946 by consolidating the General Land Office, which managed public lands, and the United States Grazing Service, which managed grazing lands in conjunction with the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934, into a single federal agency. James R. Skillen, The Nation’s Largest Landlord: The Bureau of Land Management in the American West (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), 1.

[4] Lease terms and improvement requirements changed several times between 1938 and 1976; at the outset, homesteaders had five years to build a dwelling worth $300 in materials. “Small Tract Act of 1938,” in United States Statues at Large (52 Stat. 609), June 1, 1938.

[5] Unlike the original Homestead Act, the Small Tract Act required that applicants have a stable income, which Stedman argued kept jackrabbit homesteads from being a “poor man’s bonanza.” Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 16; “Great Land Rush Swamps Bureau,” Los Angeles Times, May 13, 1957.

[6] Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 13.

[7] Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 13-14.

[8] Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 14.

[9] Randall Henderson, “Cabin on the Hot Rocks,” Desert Magazine, March 1949, 10.

[10] Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 16.

[11] Randall Henderson, “Just Between You and Me,” Desert Magazine, December 1950, 46.

[12] Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” in The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1920), 1-4; Theodore Roosevelt, “Frontier Types,” in Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (New York: The Century Co., 1899), 81-89.

[13] Charles Nordhoff, California: For Health, Pleasure, and Residence, a Book for Travellers and Settlers (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1873), 11.

[14] Everett Dick argues that the promise of obtainable land quickly surpassed religious and political persecution as the primary factor in European migration to the American colonies. Everett Newfon Dick, The Lure of the Land: A Social History of Public Lands from the Articles of Confederation to the New Deal (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1970), 1-2.

[15] Helen Bagley, Sand in My Shoe: Homestead Days in Twentynine Palms (Twentynine Palms, CA: Homestead Publishers, 1978), xv; “Luckie Park,” Twentynine Palms Historical Society, https://www.29palmshistorical.com/projects/historicSites/LuckiePark.php.

[16] Ralph Borsodi, This Ugly Civilization (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1929), 4-6; Ralph Borsodi, Flight from the City: An Experiment in Creative Living on the Land (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1933), 1, 3; Ed Robinson and Carolyn Robinson, The “Have-More” Plan: How to Make a Small Cash Income into the Best and Happiest Living Any Family Could Want (1947; repr., North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing, 1973), 3.

[17] Randall Henderson, “Just Between You and Me,” Desert Magazine, February 1946, 46.

[18] Stedman, “Jackrabbit Homesteader,” 14; Bill Moore, “Shack on the Mojave,” Desert Magazine, February 1952, 11-12.

[19] Catherine Venn, “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” Desert Magazine, July 1950, 9; Catherine Venn, “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” Desert Magazine, October 1950, 27; Catherine Venn, “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” Desert Magazine, November 1950, 23.

[20] Catherine Venn, “Diary of a Jackrabbit Homesteader,” Desert Magazine, November 1950, 23.

[21] Kim Stringfellow, Jackrabbit Homestead: Tracing the Small Tract Act in the Southern California Landscape (Joshua Tree, CA: Kim Stringfellow Press, 2016), 24.

[22] Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, “Small Tract Act: Hearings Before a Special Subcommittee,” House of Representatives, 85th Congress, 1st Session (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1958), 20, 91, 184, 186.

[23] Lisa Weiss, “Attacking Desert Shacks,” Desert Sun, June 4, 1999.

[24] For more on the consequences of desert development across the globe, see Diana K. Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016).

[25] Kristin Scharkey, “Desert Homesteads Abandoned, Not Forgotten,” Desert Sun, October 27, 2016; “Sunshine Acres: For Sale,” DesertLand.com, accessed May 5, 2023, https://desertland.com/property/lucerne-valley-california-land-sunshine-acres-0452-361-28; “Land Patent for Edward Gustav Wall (#1171092),” document, issued by the Bureau of Land Management, Los Angeles Office, May 10, 1957.

[26] Heather Murphy, “In Joshua Tree, are 1818 Airbnbs Too Many?” New York Times, April 9, 2022.