This second entry in our 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest, in which we challenged authors to write about instances where city initiatives may have “Stumbled,” is by Benjamin J. Young. He writes about the failed effort of city planners to enact zoning regulations for churches in 1950s Dallas, when faced with the nascent political clout of members of the Southern Baptist Church. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here.

Public hearings of the City Plan Commission of Dallas, Texas, were rarely well-attended, but on the evening of February 8, 1951, the commission faced a chamber filled to the brim. News had spread through the city that planners had proposed a mandate that new churches provide one paved, off-street parking spot for every ten seats in their sanctuaries. A “standing-room-only crowd” mostly made up of local Southern Baptists, Allen Quinn wrote on the front page of the next morning’s Dallas Morning News, had assembled to challenge the City Plan Commission. And they were not happy.[1]

When planners opened the floor for public comment, attendees rushed to the microphone. Wallace Bassett, who pastored Cliff Temple Baptist Church on Sunset Avenue, southwest of downtown, stressed the mandate’s implications for cash-strapped young congregations that lacked the space or funds to build parking lots, predicting that “if this is done, there won’t be any more churches started in Dallas.” Buel Crouch, a fellow Southern Baptist minister whose church lay six blocks west of Bassett’s, was more forceful in his rebuke. “If you pass this,” he warned A. Azell Adams, the commission chair, “you will hear more of Buel Crouch than you ever heard before.”[2]

Indeed, speculations circulated through the restless crowd that the City Plan Commission had nefarious intentions. Commission members vigorously denied the charge, explaining that the proposal was not discriminatory against religion, but rather part of a package of ordinances aimed at relieving traffic problems stemming from the city’s half-decade of postwar growth. Frustrated with their reassurances, Buel Crouch eventually stood up, pointed a finger at the commission, and shouted, “Just leave the churches alone!”[3] In the fight to determine where churches fit into Dallas’s expanding postwar landscape, the city’s Southern Baptists stood resolute, while planners stumbled.

On its face, the 1951 standoff between the Dallas City Plan Commission and local Southern Baptists was the climax of a feud over church zoning that had raged off and on between the two groups since 1947. Beyond the theatrics of the confrontation, however, it was a signal of the postwar growing pains that Dallas and other southern cities were experiencing as the American South’s stagnant, predominantly agrarian economy was evolving into a regional landscape marked by a constellation of fast-growing metropolises arcing eastward from Charlotte to Fort Worth. Urbanization changed the shape of the American South between 1940 and 2000. Urbanization would also, as the standoff suggested, change the shape of southern religion.

The urbanization of the South picked up steam in the 1940s, but its underlying conditions extended back to the 1920s. As historians Gilbert Fite and Jack Temple Kirby have written, the rural South remained mired in economic stagnancy and poverty in the early twentieth century. Its land struggled under a population too numerous to be supported by its meager agricultural output and with too few accessible opportunities elsewhere to alleviate that demographic burden. Southern farmers faced sagging crop prices and hard times in the 1920s, which only deepened with the onset of the Great Depression. Agricultural policymakers in the FDR administration adopted a tough-love approach to raise crop prices by instituting a system of acreage-reduction subsidies that incentivized agricultural landowners not to plant. With nearly half of the South’s cotton cultivation lands taken off-line, landowners responded by evicting tenant farmers, and the demand for agricultural wage-labor also diminished.[4] Between 1935 and 1940, the states of the former Confederacy lost 346,533 farms. The South, Gilbert Fite has argued, awaited an outlet for “the labor of millions of unneeded farmers.”[5]

With the influx of federal wartime investment in military bases and manufacturing facilities in the metropolitan South in the 1940s, such an outlet emerged. While African Americans in the rural South largely migrated northward for industrial jobs (continuing trends that had begun in the 1920s), white farm laborers flocked to southern cities like Atlanta, Houston, and Dallas, where jobs in defense-related industries abounded and suburbs radiated outward from downtown centers at a fast clip. Western suburbs of Dallas, like the Oak Cliff neighborhood and the cities of Grand Prairie and Irving, grew tremendously as the federal government sited defense plants nearby.

This initial infusion of rural migrants into Dallas and other southern cities during World War II did not stop at war’s end, but instead kickstarted decades of growth. The scale of migration that accompanied the South’s half-century shift towards urbanization was staggering. In 1940, 14 million people were living on southern farms. In 1980, less than 1.5 million remained after what Gilbert Fite has called “one of the greatest movements of people in history to occur within a single generation.”[6] During World War II alone, over 500,000 rural Texans moved to urban areas in the state, and between 1940 and 1980, the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex quadrupled in population from 711,984 to 2,719,500 residents.[7] In the years after World War II, the members of the Dallas City Plan Commission, working in an advisory role to the City Council, were tasked with channeling the flow of migrants into orderly metropolitan growth.

The 1951 church zoning standoff points to a dynamic still largely unexplored by urban historians of the South: the profound effects that postwar urbanization had on the region’s religious communities, such as the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the South’s largest white Protestant denomination. Outside of a few flagship downtown churches, the vast majority of the SBC’s millions of parishioners attended small churches dispersed across the rural South prior to World War II. A 1922 denominational study, for instance, found that 88.5 percent of Southern Baptist churches were located in the open countryside or in towns with less than 1,000 people. By the late 1930s, however, Southern Baptists were on the move. In 1936, 62.1 percent of Southern Baptists lived in rural areas; by 1951, just 39.3 percent would.[8] By the early 1940s, officials at the SBC’s Home Mission Board in Atlanta—the office in charge of overseeing the chartering of new churches—had recognized, with a sense of apprehension and opportunity, how urbanization was rapidly transforming the denomination. “Hundreds of town and country churches have lost members,” the Southern Baptist Home Missions journal reported in 1944, “while thousands of Baptists have flocked to the cities and have not yet been absorbed by the churches.”[9] SBC leaders believed that their denomination’s long-term vitality would hinge on their ability to keep pace with their parishioners’ migrations to southern cities like Dallas.

Thus, the Southern Baptist Home Mission Board hatched a grand strategy to Christianize the American South’s rapidly expanding cities. In 1941, the board organized the City Missions Program to coordinate suburban church chartering efforts with local associations of Southern Baptist churches. Under the City Missions Program, a local association of Southern Baptist churches could hire a “city missions superintendent” to coordinate the creation of new churches in their metropolitan area. The local association would employ the superintendent, but the Home Mission Board would pay his salary. Southern Baptists conceived the City Missions Program with a sense of urgency. “We must save our cities,” urged a 1942 denominational report, “if we would save our country.”[10]

Southern Baptist churches in Dallas County soon signed on to the City Missions Program, naming H. E. Fowler as city missions superintendent in 1943. Fowler served until 1952, locating land for future church sites and matching these sites with established congregations that were interested in sponsoring new ones.[11] In selecting sites, Fowler followed Home Mission Board recommendations, which encouraged local Baptist associations to target “the large group of those [people] out in the suburbs of our cities not reached and used by our churches.”[12] Fowler’s efforts achieved early success. Between 1940 and 1946, the total membership of Southern Baptist churches in Dallas County swelled from 53,689 to 77,340, and by 1952 had climbed to 120,572 adherents.[13] “People are just coming in here from all directions,” a Southern Baptist official in Dallas remarked in 1953.[14] Southern Baptists’ sharp increase in Dallas was not unique—the collective membership of the interdenominational Greater Dallas Council of Churches tripled in the fifteen years after World War II—but the common refrain from outside observers was that Southern Baptists organized new churches more efficiently than anyone else. “This religious group,” a Dallas reporter said of Southern Baptists, “has probably paced the remainder in membership gains and new congregations.”[15] “The Baptists are leading a church-building parade,” another journalist exclaimed.[16]

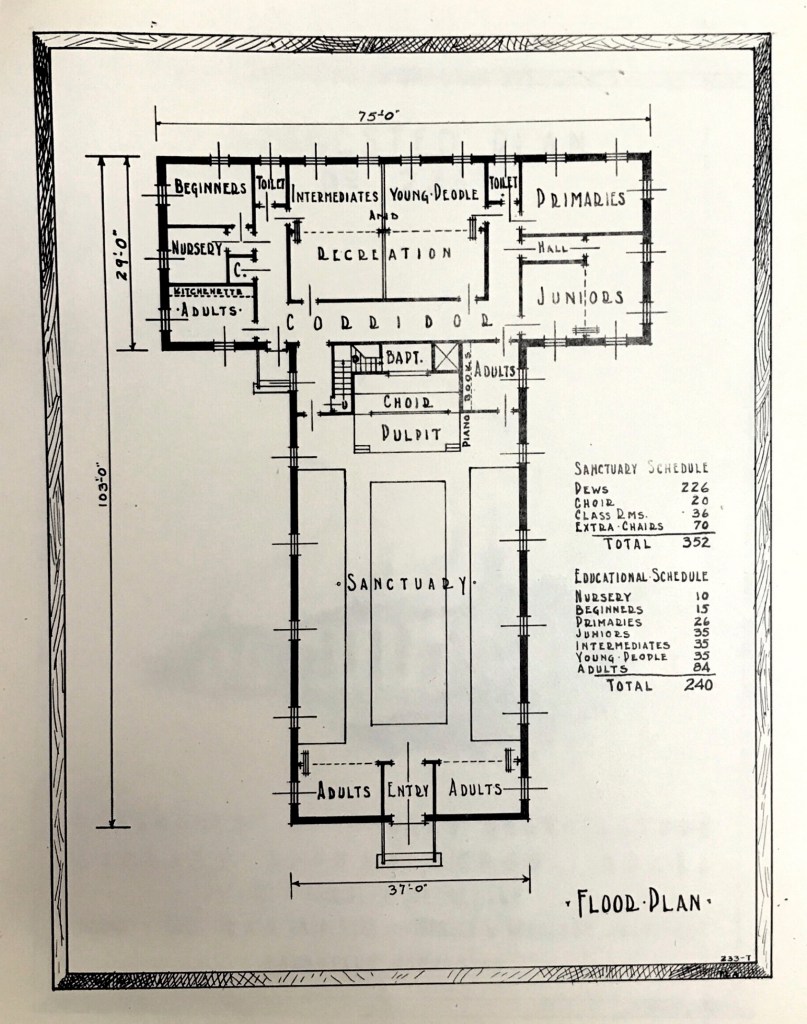

Nevertheless, the commitment of the Dallas City Council and City Planning Commission to orderly metropolitan growth threatened to rain on this parade. In part, the city’s Southern Baptists had brought this on themselves. They did everything they could to slash the costs of starting new congregations by buying up undersized residential tracts and relying on the volunteer labor of parishioners to erect simple, austere churches, with modest steeples barely peeking over the low-slung roofs of adjacent homes.[17] For these new congregations, building a parking lot for their few hundred parishioners was beyond their financial means. Besides, local pastors insisted, Southern Baptists’ strategic placement of new churches one mile apart from one another meant most congregants theoretically lived within walking distance of their nearest church.[18]

In practice, however, enough Southern Baptists were inclined to drive rather than walk that Sunday mornings in Dallas soon found narrow suburban streets clogged with cars of the faithful, angering neighbors and subverting the tenor of what city planners had intended to be quiet neighborhoods.[19] The Dallas Morning News reported that at one city council meeting in March 1947, a “gray-haired Mrs. O. A. Bass” lodged a complaint against Word Avenue Baptist Church, which had opened near her home in northeast Dallas. “I’m a Baptist,” she explained, “but they don’t need another church in that neighborhood; they ought to go where they can get parking.”[20] In response, the Dallas City Council shortly thereafter unveiled a zoning proposal that would require new churches to maintain an adjustable ratio of paved, off-street parking spaces to sanctuary seats.[21]

Southern Baptists in Dallas, like denominational officials who organized the City Missions Program, had staked their future on building new churches in the city’s burgeoning suburbs. Since the parking-space mandate would significantly inflate the costs of continuing their church-building spree, they perceived it not as a commonsense zoning measure, but as an existential threat. When the proposal first surfaced in 1947, local Baptists formed a special committee to fight the ordinance, led by A. C. Turner, pastor of Forney Avenue Baptist Church. Turner and his fellow committee members attended public meetings of the City Plan Commission and successfully lobbied for the City Council to scrap the measure.[22] Their quick mobilization to fight against the proposal, and the fervor of their opposition, was rooted in a clear-eyed rationality about its implications for an urbanizing SBC.

The fact that Southern Baptists stood somewhat (though not entirely) aloof from the upper echelons of Dallas’s civic elite heightened tensions. Southern Baptists were the city’s largest denomination, but the 1947 Dallas City Council included three Methodists, two Presbyterians, two Episcopalians, one Jew—and no Southern Baptists. Woodall Rodgers, who served as Dallas mayor from 1939 to 1947, was well-known to be a progressive Presbyterian. While a few older Southern Baptist churches, like the First Baptist Church downtown, attracted members of the city’s leadership class, it is telling that Buel Crouch and Wallace Bassett, two of the loudest Baptist voices in the church-zoning fight, pastored churches in Oak Cliff, a working- and middle-class suburban neighborhood southwest of downtown.[23]

Battles over the church zoning proposal flared up repeatedly after the spring of 1947, revealing both the persistence of Dallas’s city planners and the stubbornness of the city’s pastors. In the summer of 1948, the City Plan Commission reintroduced the church parking ordinance, but local Southern Baptist pastors once again convinced the City Council not to act on the Commission’s recommendation.[24] A few months later, in January 1949, the City Plan Commission took up the church parking issue again, adding to their proposal a minimum lot-size requirement for churches aimed at keeping them out of residential areas. Turner made his displeasure at both measures known at a subsequent City Plan Commission hearing. It was “not an anti-parking law,” he told planners. “It is an anti-church-building law. You are treading on sacred ground.”[25] The City Council subsequently struck both measures from the set of zoning ordinances they passed that March.[26]

Hence, when the City Plan Commission again proposed a church parking mandate in 1951, the patience of local Southern Baptists was wearing thin. In the chambers of the City Plan Commission, it snapped. Reverend Buel Crouch’s outburst, the standing-room-only crowd—all these factors convinced the members of the City Plan Commission to table the ordinance at the end of the dramatic meeting. Southern Baptists had won a permanent victory, as the City of Dallas would not meaningfully revisit the possibility of instituting zoning regulations on churches again until the 1980s.[27]

What, then, does Dallas’s Southern Baptists’ hard-fought zoning exemption illustrate? By the 1940s, Southern Baptists were becoming an increasingly conspicuous presence in southern cities like Dallas as their rural congregants moved in large numbers into nascent suburbs. As Dallas grew, so would their churches. And nationally, the SBC became the largest Protestant denomination in the United States in the late 1960s. Nearly three quarters of its total membership was now urban, a sea change from its solidly rural status just three decades prior.[28]

Further, Southern Baptists’ hard-fought victory against church zoning in Dallas meant that they were free to integrate their churches into the spatial patterns of city’s rapid growth with few restrictions. This precedent still held in the early 1980s, when far north Dallas was home to Prestonwood Baptist Church, the fastest-growing Southern Baptist church in the country at the time. Prestonwood attracted the ire of its neighbors when it affixed to its roof a cross “so high you can see it wherever you are in the north Dallas area.” Their complaints against the church went nowhere, however, for as the Dallas Housing and Neighborhood Services noted, “the height of the cross violates no zoning or building ordinance.”[29] Prestonwood was a symbol of what the Dallas Baptists’ victories in the postwar church zoning battles wrought even three decades later, at a scale that dwarfed the small neighborhood churches at the center of the original dispute.

Southern Baptists’ zoning dispute with the City Plan Commission also revealed them as active participants in Dallas politics, who often embraced their newcomer statuses to array themselves against the community’s established planning circles and government. These impulses would endure, even as the issues motivating the city’s Southern Baptists evolved over the post-World War II decades. In the late 1950s, for instance, Buel Crouch and Wallace Bassett spearheaded a successful campaign to make their Oak Cliff neighborhood a dry precinct, once again outmaneuvering the business and civic elite downtown, which opposed the measure on economic grounds.[30] Indeed, in the late 1970s, a new generation of Southern Baptist megachurch ministers, many of whom were based in Dallas, became central organizers of a coalescing Christian Right. Busy building a religion fine-tuned for the South’s increasingly suburban future, Southern Baptists’ ability to adjust to and leverage the emerging metropolitan landscapes of the post-World War II South underwrote their rise in influence in late twentieth-century American life.

Benjamin J. Young is a PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Notre Dame. His research concerns the intersection of religion, political economy, and urban life in the modern United States. He is currently at work on his dissertation on evangelicals and the rise of the metropolitan South in the post-World War II era.

Featured image (at top): “U.S. Highway 80, Texas, between Fort Worth and Dallas” (1942), Arthur Rothstein, Farm Security Administration—Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Allen Quinn, “Baptists Again Beat Down Off-Street Parking Project,” Dallas Morning News (hereafter DMN), February 9, 1951.

[2] Quinn, “Baptists Again Beat Down Off-Street Parking Project.” Locations of Cliff Temple Baptist Church and Grace Temple Baptist Church are from Dallas City Directory, 1944–1945 (Dallas, TX: John F. Worley Directory Company, 1944), 1747–48.

[3] Quinn, “Baptists Again Beat Down Off-Street Parking Project.”

[4] Fite, Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture, 1865–1980 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984); Jack Temple Kirby, Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1987), 51–79; Roger Biles, The South and the New Deal, 2nd ed. (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006).

[5] Fite, Cotton Fields No More, 157, 162.

[6] Fite, Cotton Fields No More, 209.

[7] James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 32–33; Sean P. Cunningham, Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2010), 23. The Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area did not exist until 1970, so the figures here represent the aggregate population of Dallas County, Tarrant County, Denton County, Collin County, and Rockwall County. See “Decennial Census by Decade,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade.html.

[8] Southern Baptist Handbook, 1923 (Nashville, TN: Sunday School Board, Southern Baptist Convention, 1924), 14.

[9] “Population Drifts,” Southern Baptist Home Missions, March 1944, 3; Nancy Tatom Ammerman, Baptist Battles: Social Change and Religious Conflict in the Southern Baptist Convention (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 52.

[10] Annual of the Southern Baptist Convention, Nineteen Hundred and Forty-Two (Nashville, TN: Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention, 1942), 256.

[11] Annual of the Southern Baptist Convention, Nineteen Hundred and Forty-Four (Nashville, TN: Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention, 1944), 308–9; Carr M. Suter Jr., Dallas – The Doorway to Missions: The Centennial Story of Dallas Baptist Association (1903-2003) (Dallas, TX: Dallas Baptist Association, 2003), 22.

[12] Annual of the Southern Baptist Convention, Nineteen Hundred and Forty-Three (Nashville, TN: Executive Committee of the Southern Baptist Convention, 1943), 239.

[13] Dorothea Lyle, “Churches Ride Financial Crest,” DMN, December 2, 1946. Charles McLaughlin, “New Churches,” Southern Baptist Home Missions, May 1956; Suter, Doorway to Missions, 22. The 1952 comprehensive survey was funded by the National Council of Churches. Its dataset is available from the Association of Religion Data Archives, https://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Downloads/CMS52CNT_DL2.asp.

[14] Stewart Doss, “Tremendous Building Program Under Way by Religious Groups,” DMN, October 11, 1953; Robert B. Fairbanks, “Planning the Suburban City in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex,” in Paul J.P. Sandul and M. Scott Sosebee, eds., Lone Star Suburbs: Life on the Texas Metropolitan Frontier (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019), 51–56; Sean P. Cunningham, American Politics in the Postwar Sunbelt: Conservative Growth in a Battleground Region (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 29.

[15] Doss, “Tremendous Building Program”; “Huge Outlay Goes to New Churches,” DMN, December 21, 1952; John C. Perham, “Rising Spires: Record Church-Building Has a Secular Impact, Too,” Barron’s, July 5, 1954, 3, 10, 16; Nina McCain, “Churches and Their People Wield Vast Influence,” DMN, April 24, 1960.

[16] Walter S. Robinson, “Industrial Works Keep County’s Boom Rolling,” DMN, May 20, 1956.

[17] Floyd Poe, “This, That and the Other,” DMN, November 3, 1954; O. C. Robinson Jr., “The Salvation of Our Cities,” Southern Baptist Home Missions, July 1956, 10; “Baptists Volunteer Services for Building of New Church,” DMN, September 15, 1946; “Baptists Turn Builder,” DMN, March 30, 1947; Walter Robinson, “Duncanville Church to Lay Cornerstone,” DMN, October 1, 1948; “Mesquite Baptists to Have New Church,” DMN, September 19, 1954.

[18] “Pastors Rap Parking Idea,” DMN, March 9, 1947; Robinson, “Industrial Works Keep County’s Boom Rolling.”

[19] Henry C. Withers, “Church Parking Is Big Problem,” DMN, March 14, 1949.

[20] “Church Park Space Backed,” DMN, March 13, 1947.

[21] “Pastors Rap Parking Idea,” DMN, March 9, 1947; “Church Park Space Backed,” DMN, March 13, 1947; “Opposition Seen to Church Zoning and Parking Bans,” DMN, July 9, 1948.

[22] “Pastors Rap Parking Idea,” DMN, March 9, 1947; “Opposition Seen to Church Zoning and Parking Bans,” DMN, July 9, 1948.

[23] “Opposition Seen to Church Zoning and Parking Bans,” DMN, July 9, 1948. On the religious make-up of the 1947 Dallas City Council, see “Ticket Announced by Charter Party,” DMN, February 27, 1947; “Roland Pelt Honored by Oak Cliff CC,” DMN, March 5, 1952; “Aims Voiced in Statement by Savage,” DMN, April 25, 1954. Of the nine members of the 1947 Dallas City Council, I failed to identify the religious affiliation of one councilman, Everett Fox.

[24] “Zoning Rules on Churches Restudied,” DMN, July 7, 1948; “Opposition Seen to Church Zoning and Parking Bans,” DMN, July 9, 1948.

[25] “Pastor Hits Zoning Law for Church,” DMN, March 9, 1949; “Opposition Seen to Church Zoning and Parking Bans,” DMN, July 9, 1948.

[26] “Pastor Hits Zoning Law for Church,” DMN, March 9, 1949; Withers, “Church Parking Is Big Problem”; “Council Kills Parking Rule at Churches,” DMN, March 18, 1949.

[27] “Plans Made to Revamp Zone Codes,” DMN, October 6, 1950; “Off-Street Parking for Churches Eyed,” DMN, January 26, 1951; “Ministers Set Discussion of Parking Issue,” DMN, February 3, 1951; “Debate To Be Aired on Church Parking,” DMN, February 7, 1951; Quinn, “Baptists Again Beat Down Off-Street Parking Project”; Helen Parmley, “Hundreds Turn Out to Oppose Church Zoning,” DMN, March 6, 1984.

[28] Dean M. Kelley, Why Conservative Churches Are Growing (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1972), 21–22; Ammerman, Baptist Battles, 52.

[29] “Line One,” DMN, August 29, 1982; W.L. Taitte, “Amazing Place,” D Magazine, December 1983.

[30] Helen Bullock, “Oak Cliff Group Asks Petition for Beer Vote,” DMN, September 24, 1956; Bill Glines, “Drys Map Campaign,” DMN, August 5, 1957; “‘Dry City’ Trade Cut Feared by Hotelman,” DMN, August 13, 1957; “Cabell Vows Neutrality on Alcohol,” DMN, April 11, 1959. On the Oak Cliff prohibition campaigns, see A. K. Sandoval-Strausz, Barrio America: How Latino Immigrants Saved the American City (New York, NY: Basic Books, 2019), 71.