Welcome to the first entry in our 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest! Our theme this year is “Stumble.” Aimée Plukker studies the history of tourism, and in this essay considers what tourists are and are not supposed to stumble across, and how cities treat welcome and unwelcome visitors. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here.

In the academic year 2022-2023, I travelled through several European countries and cities, collecting materials for my dissertation on post-WWII US tourism to Rome, Berlin, and Amsterdam.

Rome, October 2022

Under the Ponte Sant’Angelo, the bridge originally built in 134 CE by the Roman emperor Hadrian to cross the Tiber and connect the city center with his mausoleum (today known as Castel Sant’Angelo), I stumbled upon the tent of a homeless person. The bridge offered protection from the rain; the statues of the ten angels on the bridge perhaps offered some spiritual protection, as they hold the instruments of the Passion, or weapons of Christ, referring to salvation. On the horizon was the dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica; it serves as the background of the many selfies that countless numbers of tourists have taken while crossing the bridge, probably unaware of the fact that they walk on the roof of someone who lives below, in a tent. There is no place for tents in the idealized tourist imaginary of Rome.

The tent under the Ponte Sant’Angelo was certainly no exception. Passing the Vatican and Saint Peter’s Square at night, I saw an abundance of tents, sleeping bags, and cardboard boxes, a striking contrast when one thinks about the wealth and extravagance of the buildings that surround these temporary homes. Even more surprising was the number of tourists that were still outside in the dark to gaze upon the basilica, as an animated film with booming sound was projected on the façade of the church. The spectacle told, among others, the story of Saint Peter, who received the keys to heaven and was the first bishop of Rome. I wondered how often the people in tents had listened to the story, as they lived so close to the spectacle. With plenty of references to salvation in the afterlife to be found within the city, little solace is offered to some of Rome’s and the Vatican’s undesirable inhabitants.

In such a major tourist destination, the urban environment lays bare the disparity between welcome and unwelcome visitors—if one pays attention to it. The Via dei Fori Imperiali, a road built under Mussolini and connecting Rome’s ancient forum with the Colosseum (also used to impress Hitler during his visit in 1938), was closed to traffic in 2013.[1] The mayor at that time, Ignazio Marino, member of the center-left Democratic Party, implemented the pedestrianization of the area to spare the monuments, hoping to “turn the whole area into an archeological park.”[2] Ten years later it is almost impossible to use this road during daytime, as large groups of meandering tourists crowd together and block the entry to the Colosseo Metro Station. While the area around the Colosseum was cleared to preserve Rome’s heritage and offer more space for tourists, I saw posters on buses, city walls, and billboards during the September 2022 elections conveying a clear message about unwelcome visitors. “Stop the boats!” was literally one of the slogans of the Italian right-wing party Lega Nord, referring to the boats trying to reach “fortress Europe” by crossing the Mediterranean from the African continent.

A couple months later, I found a booklet on tourist publicity in the National Archives of the Netherlands. The booklet was published for a symposium of the International Union of Official Tourism Organizations in 1964. It informs that: “Whilst the tourism image stresses the existence in a country of areas and regions in which the rigours and disadvantages of modern industrial life are not present, to succeed in attracting tourists it also must convey a picture of up-to-date tourist facilities including modern, well-run hotels, a high standard of living, good roads, railways and airports, etc.”[3] This quote emphasizes the tourism image as spectacle, as also described by Guy Debord, enhancing the realities of the real urban environment.[4]

Termini, Rome’s main train station, has many modern features, and was frequently promoted as such when it was finished after WWII. Nowadays, thanks to its large roof and the nearby homeless shelter, Binario 95, in the Via Marsala, the train station is also one of the most popular living spaces for homeless people in the city. Binario 95 estimated that 20,000 people are living on the streets in Rome, while the city can only provide beds to 5% of the homeless; at the same time there are almost 25,000 officially registered Airbnb listings in Rome, and no regulation on short-term rentals.[5] It is also important to note here, as sociologist Marco d’Eramo explains, that since indigenous owner-residents go to live in the suburbs or in the countryside, where life is cheaper, “the economic impact of tourism extends beyond the historic centers, beyond the cities.”[6] The “high standard of living” conveyed in the 1964 booklet to attract tourists is only available to the select few, and is an asset that needs to be protected from “invaders” at all costs. (A recent Dutch newspaper article states that the current European border walls, consisting of fences, concrete walls, cameras and barbed wire, are 14,647 km (9,101 miles) long and that because of the growth of walls on land, more migrants take boats—36,000 people in the first months of 2023, compared to 16,000 in 2022.[7] Another example is the film footage of armored vehicles and soldiers holding back migrants taken at the border of Ceuta between Morocco and Spain in 2021.[8])

Florence, December 2022

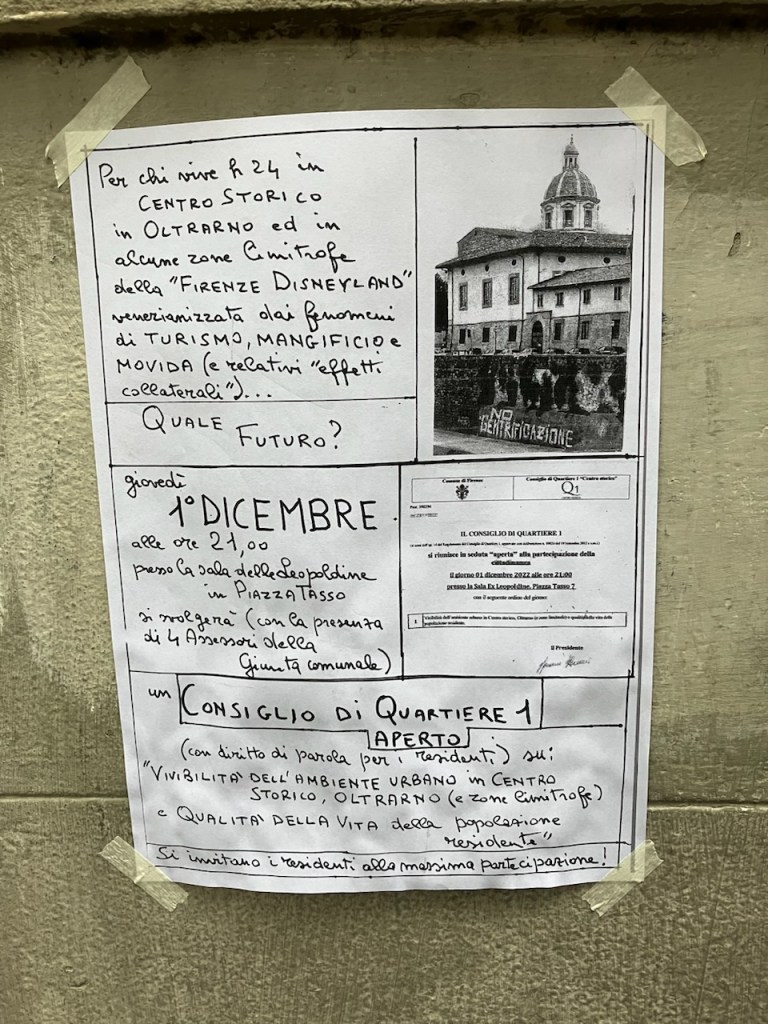

On my way to the Netherlands Interuniversity Institute for Art History (NIKI) in Florence, I saw a poster on the light-yellow stone wall of a house in the Via Romana. The poster calls for the inhabitants of “Firenze Disneyland” to attend a meeting to discuss the future of the city, which is increasingly being flooded with tourists. How can the quality of life for residents be sustained with the continuing growth of the leisure industry? “No gentrification” says the graffiti on the photograph that is included on the poster.

The term Disneyfication has increasingly appeared in recent decades, referring to—in the words of professor of urban planning Frank Roost—a process in which many city centers are slowly transforming into staged shopping and entertainment areas with Disney-like qualities because of the growth of tourism and free time.[9] In the case of Florence: English menus, paying entrance fees to visit churches, and selling “authentic” leather bags. As sociologist Dean MacCannell already noted in the 1970s, within the leisure industry “staged authenticity” quickly takes over in order to please tourists and confirm the advertised tourism image.[10] On my research trip through Europe, I noticed that local or national “authentic” identities, have become more misplaced, intertwined, and adjusted to fit a U.S. version of “European.” Madrid and Rome have multiple CBD stores called “Cannabis Store Amsterdam,” and in the Roman neighborhood Trastevere—also known amongst Italians as “Lunapark (Theme Park) for Americans”—street vendors sell lavender products typical for the Provence region of France. Earlier that year, I heard an accordionist on a square in Perugia, Italy, playing Yann Tierssen’s famous songs composed for the French film Amélie, which takes place in Paris.

Besides the urban monoculture created by the tourist industry, “Firenze Disneyland” also impacts the residents of the city in other ways, for instance because of its nightlife (read: drunken and loud tourists), as the poster points out. These problems with overtourism are not an issue only in Florence. Complaints about the number of tourists are common in other popular destinations, like Barcelona, Dubrovnik, and Amsterdam. In March 2023 the municipal government of the latter even released a campaign titled “Stay Away” to discourage tourists from visiting the city.[11] The campaign (which very quickly became a running joke among people of my age living in Amsterdam) especially targets British men between the age of 18 and 35, who are stereotyped as sex and drug tourists only looking for pubs and trouble on their ladventures. This campaign shows that some tourists are not welcome visitors either.

The tourist publicity booklet from 1964 also states that: “A visual presentation which does not do full justice to the area’s customs and attitudes has the ultimate results of reducing both number of visitors and revenue for the tourist industry” (emphasis mine).[12]

When you are a tourist, you are not supposed to stumble upon things outside of the tourism image of the city being sold. You only see a curated image of the local customs and attitudes, a view of the city that tourism policymakers and advertising specialists helped to create to sell a destination. So who decides what entails the area’s customs and attitudes? What happens if the tourism image turns the city into a frozen place, driving out the locals that gave charm to the city and constructed its attraction in the first place? And who becomes excluded from the city in this process, when the main goal of the tourism industry is revenue, as the example from the booklet indicates?

During my research and travels in Europe I have seen the disparities between “tourists” and “cosmopolitan/digital nomads,” on the one hand, and “migrants,” “refugees,” “aliens” and “intruders,” on the other.[13] While the archives I visited reveal how the carefully constructed enhanced tourist image of the city was widely promoted by politicians, tourism policymakers, and tourist businesses after the Second World War to stimulate European economic recovery, the examples from my encounters also illustrate how the mass tourism industry brings to light a tension that has grown throughout the intervening years, between welcome and unwelcome visitors, in a society that has become increasingly driven by revenue and profit.

Aimée Plukker is a PhD candidate in modern European history at Cornell University. Her dissertation, “Transatlantic Civilization: Cold War U.S. Tourism to Rome, Berlin and Amsterdam,” explores how tourism contributed to the creation of “the West” as a cultural and political identity. Aimée is also the reviews editor of the Journal of Tourism History.

Featured image (at top): Ponte Sant’Angelo and tent, photograph by author.

[1] See for instance this fragment on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9k5zNrKQL8. The road is clearly visible at 4:17. Atelierdesarchives History, “1938 – Visite d’Hitler à Rome,” YouTube.com, accessed May 25, 2023.

[2] “Rome’s Mayor Bans Cars from Street Near Colosseum,” http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2013/8/3/cars-banned-on-colosseumstreetbyromescyclingmayor.html, May 3, 2013. The impact of vibrations caused by traffic on the uncemented stones of the Coliseum was already an issue in 1956: Universal Newsreel, vol. 29 no. 77, September 17, 1956, National Archives and Records Administration, Maryland, USA.

[3] Tourist Publicity. Policy Strategy Implementation Measurement. IUOTO Symposium Dublin March 1964, Nationaal Archief, The Hague, ANVV 2.19.029, 25, “Introduction,” 10.

[4] Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (New York: Zone Books, [1967] 1998).

[5] Leonardo Bianchi, “Photos of Rome’s Hidden Side Along the Tiber River,” https://www.vice.com/en/article/m7vn9v/tiber-river-rome-photos, May 26, 2022. The article describes the project “The Tevere Grand Hotel” of photographer Marco Sconocchia who photographed along the Tiber for a year, you can see the result here: https://marcosconocchia.org/tevere-grand-hotel-1, accessed July 20, 2023. The Airbnb statics are from the following article, which also includes interesting interviews with a resident of a popular tourist neighborhood in Rome, a municipal councilor, and a sociologist who wrote a report on short-term rentals: Eric Reguly, “Overladed by Airbnbs and mass tourism, Rome fears its historic center will be emptied out of locals,” https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-rome-tourism-airbnbs-locals/#:~:text=There%20almost%2025%2C000%20Airbnb%20listings%20in%20Rome, June 4, 2023.

[6] Marco d’Eramo, The World in a Selfie: An Inquiry into the Tourist Age (London: Verso, 2021), 80. Original: d’Eramo, Marco, Il selfie del mondo. Indagine sull’età del turismo (Milan: Feltrinelli Editore, [2017] 2019).

[7] Derk Walters et al., “Hoe Europa zijn grenzen bewaakt,” https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2023/05/11/hoe-europa-zijn-grenzen-bewaakt-a4164428, May 5, 2023.

[8] “Spain Vows to Restore Order After Thousands Swim into Ceuta from Morocco,” https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/spain-deploys-army-ceuta-patrol-border-with-morocco-after-migrants-break-2021-05-18/, May 18, 2021.

[9] “Aufgrund der wachsenden Bedeutung von Freizeit- un Konsumdiensten haben sich die Zentren vieler Städte langsam in inszenierte Einkaufs- und Unterhaltungsbereiceh mit Disneyland-artigen Qualitäten verwandelt,” Frank Roost, Die Disneyfizierung der Städte. Großprojekte der Entertainmentindustrie am Beispiel des New Yorker Times Square un der Siedlung Celebration in Florida (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2000), 10.

[10] Dean MacCannell, “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings,” American Journal of Sociology 79 (1973): 589-603.

[11] “Stay Away,” https://www.amsterdam.nl/nieuws/nieuwsoverzicht/stay-away/, accessed May 25, 2023, webpage currently removed from the municipal website. See instead Anna Holligan, “Amsterdam launches stay away ad campaign targeting young British men,” https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-65107405, March 29, 2023.

[12] Tourist Publicity. Policy Strategy Implementation Measurement, “Publicity Policy in the Field of Tourism,” 19.

[13] As Kathleen M. Adams and Natalia Bloch point out in the introduction to their edited volume that explores the intersection of tourism, migration, and exile, there is often a semantic division here between the Global North and the Global South. Kathleen M. Adams and Natalia Bloch, “Problematizing Siloed Mobilities. Tourism, Migration, Exile,” in Adams and Bloch eds., Intersection of Tourism, Migration, and Exile (London/New York: Routledge, 2022), 1-30, 3.