Begun initially as a blog in 2015, before expanding to include photographs, maps, and other historical artifacts, Building the Black Press explores the publishing plants, corporate offices, and production spaces used by Black periodicals and their contributors from the nineteenth century to the present day. It highlights why Black press buildings matter—as sites of historic protest and identity formation, as symbols of Black pride and business success, and as windows into the fluid and often fraught relationship between race, space, and media in the modern American city. The Metropole sat down with the website’s founder, historian E. James West to discuss the site, the Black press, and digital humanities.

How did Building the Black Press come into existence?

The project is an outgrowth of a Leverhulme early career fellowship I held in the United Kingdom. The focus of my fellowship was the completion of a monograph about the Black press and the built environment in Chicago titled A House for the Struggle, which was published in 2022 by the University of Illinois Press. However, a digital history component, exploring the broader history and significance of Black press buildings in the United States, was written into my funding bid and was always part of my larger ambitions for the project.

Why focus on the architecture of the Black press? What does it tell us about the importance of Black newspapers?

There has been a groundswell of scholarship on the Black press over the past two decades that has helped to deepen our understanding of the historic role of Black periodicals as a “voice for the race.” Thinking about Black press buildings allows us to consider what this means in more concrete terms. Black editors, journalists, and readers, both consciously and unconsciously, positioned Black press buildings as symbols of racial protest and Black achievement. Conversely, this symbolism made such buildings a target for white backlash, reflecting the broader efforts of white detractors to suppress or undermine the advocacy role of the Black press.

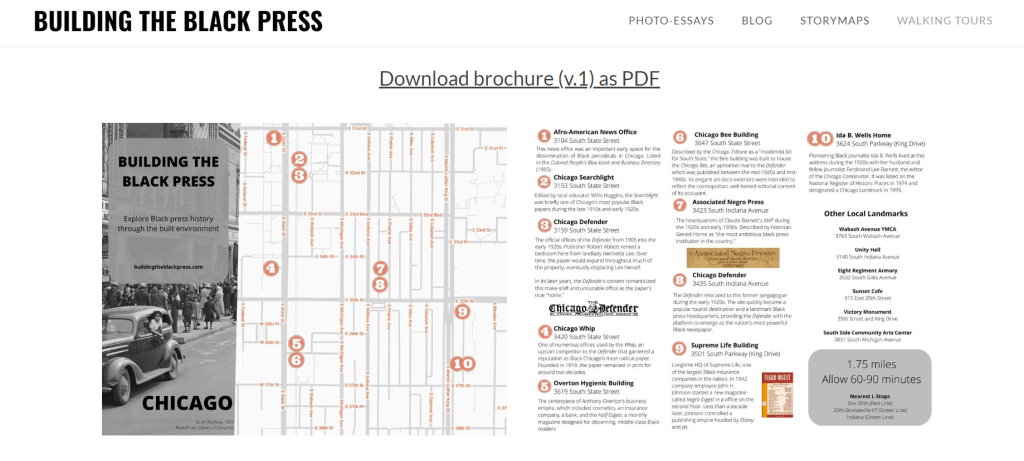

I also think there is much more to unpack about the institutional impact of Black periodicals and Black publishing enterprises within Black urban communities, and that their building histories offer a way of thinking about this broader function. In a similar way to spaces such as Black churches or Black schools, Black media buildings were literal community anchors. They weren’t just sites of editorial production, but were also political hubs, artistic spaces, tourist destinations, rallying points, civic landmarks, etc. Mapping these spaces helps to give form to the more amorphous role of the Black press in representing, curating, and defending Black lives.

How did the Black press, both in its reporting and in its architectural choices, engage with the field of architecture more generally? What does this tell us about the press and the field of architecture?

It’s an interesting question, because there are relatively few Black publications that generate the kind of capital needed to build their own headquarters from scratch. Often, we see spaces that are repurposed or reappropriated in ways that provide interesting commentary on larger cultural and demographic shifts. For example, in Chicago, the Defender’s first major offices had actually been constructed as a synagogue. The building’s transition from Jewish to Black ownership, and the adaptations that the newspaper made to transform the building into a Black print hub, reflected the out-migration of Chicago’s South Side Jews and the influx of African Americans as part of the first wave of the Great Migration.

The flip side to this is that when Black print enterprises are able to finance their own buildings, they really lean into the relationship between building structure and editorial style, presenting their locations as a literal extension of the printed word. In Chicago, this is most clearly articulated through the Chicago Bee building, with an Art Deco design meant to reflect the aspirational, tasteful editorial tone of its namesake, and the striking interiors and exteriors of the Johnson Publishing Building at 820 South Michigan Avenue, envisioned by publisher John H. Johnson as a monument to the importance of his publishing company and the broader gains made by African American communities during the decades following World War II.

In terms of architectural commentary, Black periodicals have long celebrated Black architects and documented the achievements of figures such as Paul Williams and Albert Cassell. This was part of the press’s function as an advocacy press and another example of ongoing efforts to counteract white cultural hegemony. They have also been critical of architectural or construction projects that are perceived to negatively impact Black communities. A prominent example of this is the wave of post-World War II urban renewal projects that reshaped many urban centers, with the Black press leading critiques of urban renewal as “negro removal.”

Building the Black Press utilizes photography, narrative based on primary and secondary sources, and story maps, and provides self-guided walking tours. How did you decide on this approach to the site and what are its benefits?

I think the project’s narrative dimension is important for establishing the overarching significance and function of Black media buildings. Images of or information about individual buildings might carry a degree of interest for researchers or casual readers who are interested in the subject. However, to articulate the broader aims of the project and help audiences make connections between different Black press enterprises across time and space, the story-telling aspect is valuable.

The mapping dimension was, for me, always a necessary part of rooting the project and the buildings it covers within the communities and cityscapes that they live in. Having a sense not just of what buildings looked like and how they functioned, but where they stood in relation to each other and to other Black civic, social, and political spaces, was vital to building a larger and more complex urban geography.

Since you’ve launched the site, who has the audience been, how have they engaged with the site, and in what ways does the audience’s engagement align with your expectations or challenge them?

From the engagement I’ve had and from comments I’ve received through the site, it’s been a pretty diverse group of people. One obvious audience group has been my own students—I’ve integrated the site into my own teaching, most notably through a digital history course on a Masters degree program I was teaching at my previous institution. Students have enjoyed engaging with the site, and it has also been useful for them to get direct, practical feedback on how the site developed, which fed into the development of their own digital history projects. For me, this has carried the added benefit of generating more feedback on the site’s functionality and resources—both good and bad—which I’ve used to adapt and develop the site further.

How has being based in the United Kingdom affected the project? In general, what have been the biggest challenges you’ve encountered?

In terms of generating content for the site, it’s not been too bad. Certainly, the site would include a lot more original photographs if I was based in the United States and many of these sites were more easily accessible to me. I actually think the mapping component is perhaps more pronounced, given my physical distance from many of the buildings that are cataloged on the site. Creating these types of resources was an important part of helping me get to grips with Black press geography and to think practically about how the editorial and political relationships that developed between different publications were informed by their spatial proximity to, or distance from, one another (and how this proximity changed, or didn’t, over time).

Did working on Building the Black Press lead you to any new conclusions regarding this history? Did it reinforce previous ideas you had or alter them?

I think it’s really deepened my understanding of the broader significance and contributions of Black periodicals to Black communities, particularly Black urban communities, in ways that go far beyond editorial content. The shift from thinking about Black periodicals as individual publications to community institutions is made manifest through the multivalent and multifaceted use of the buildings they occupied. It’s also made me think a lot more about the present-day role of the Black press and the continued importance of the connections between race, space, and media production.

Where do you place Building the Black Press in the general sphere of digital humanities? What is the future for digital humanities?

It’s certainly connected to and has been inspired by the development of Black digital humanities—whether we view this designation as a specific field or more of a “constructed space to consider the intersections between the digital and blackness.” Centers such as the Center for Black Digital Research at Penn State University and the African American Digital and Experimental Humanities Hub at the University of Maryland are fantastic models for the kinds of transformative scholarship that can be generated through such initiatives. Building the Black Press obviously has a more limited scope and much smaller budget than larger, more collaborative digital humanities projects such as the Colored Conventions Project or Mapping Inequality. However, I think it highlights some of the ways in which we can utilize digital tools to explore big questions about American identity, urban history, media production, and racial politics.

In terms of the future, I think it’s vital to continue to reflect critically on how race (among many other social constructions and categories of identity) factors into the continued development of digital humanities. As my colleague Kim Gallon articulates, “what do we do with forms of humanity excluded from or marginalized in how we study the humanities and practice the digital humanities? What are the implications of using computational approaches to theorize and draw deeper insight into a modern humanity that is prima facie arranged and constructed along racial lines?” For digital humanities to be truly liberatory, these questions must remain at the center.

Additional Digital Summer School 2023 (DSS 2023) Entries:

E. James West is a Lecturer in Interdisciplinary Societies and Cultures at University College London. He is the author of three books, including A House for the Struggle: The Black Press and the Built Environment in Chicago (University of Illinois Press, 2022).

Featured image (at top): “Linotype Operators of the Chicago Defender, Chicago, Illinois” (1941), Lee Russell, Farm Security Administration Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.