Picturing Urban Renewal is a history of urban renewal from the bottom up. The urban renewal story typically is told from the perspective of politicians and urban planners. This website gives voice to displaced residents and business owners, community activists, reporters, gentrifiers, and construction workers, as well as to politicians and planners. The goal of its creators is to build a broader public understanding of this controversial policy and its short- and long-term effects. They hope to move the public conversation beyond whether urban renewal was “good” or “bad” and to focus on the “how” and “why.” The Picturing Urban Renewal team, David Hochfelder, Ann Pfau, Stacy Sewell, Don Button, and Juliet Jacobson, sat down with The Metropole to discuss their forthcoming project.

How did this project come into existence and why the focus on urban renewal?

Albany, NY, was the first of four cities we started researching. (The other three are Newburgh, Kingston, and New York, NY.) Albany was the site of the enormous state-funded redevelopment project, the Empire State Plaza. There are three historians on the Picturing Urban Renewal team: David Hochfelder and Ann Pfau, both of whom live in Albany, and Stacy Sewell, who grew up there. In the New York State archives, we discovered a vast cache of photographic negatives taken by the State in order to compensate property owners and the more than 7,000 people displaced. The photos, from the early 1960s, were fascinating. Unlike most such collections, they included interiors as well as exteriors. Some featured portraits of the occupants, with their families and furnishings.

This find was the first step toward what would become Picturing Urban Renewal. We began by creating a blog, 98 Acres in Albany. We tracked down and interviewed the children of former residents as well as the construction workers who got their start on the Empire State Plaza. Later, we uncovered similar photographic collections in the other three cities, and so the idea for Picturing Urban Renewal was born. To make this idea a reality, we partnered with a pair of experienced and innovative media developers, Don Button and Juliet Jacobson of DigitalGizmo, and applied for National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) funding. We have received NEH planning and prototyping grants and are currently pending for production funding.

Even in its prototype stage, it’s clear Picturing Urban Renewal is approaching the subject somewhat differently than similar projects looking at redlining, such as Mapping Inequality, and the more recent project Renewing Inequality, which does focus on urban renewal and utilizes extensive mapping. Why have you chosen to focus more on images and not maps?

Those projects are great examples of using maps to present important aspects of urban history. They served as an early inspiration for our work, and we’ve used them to great effect in many of our public presentations.

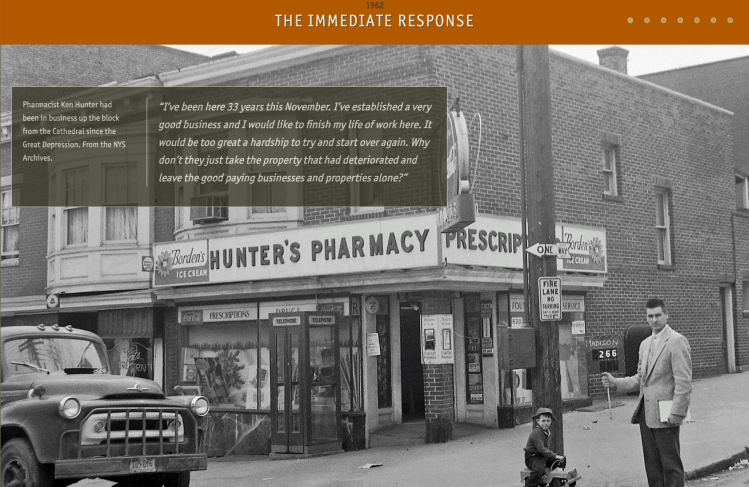

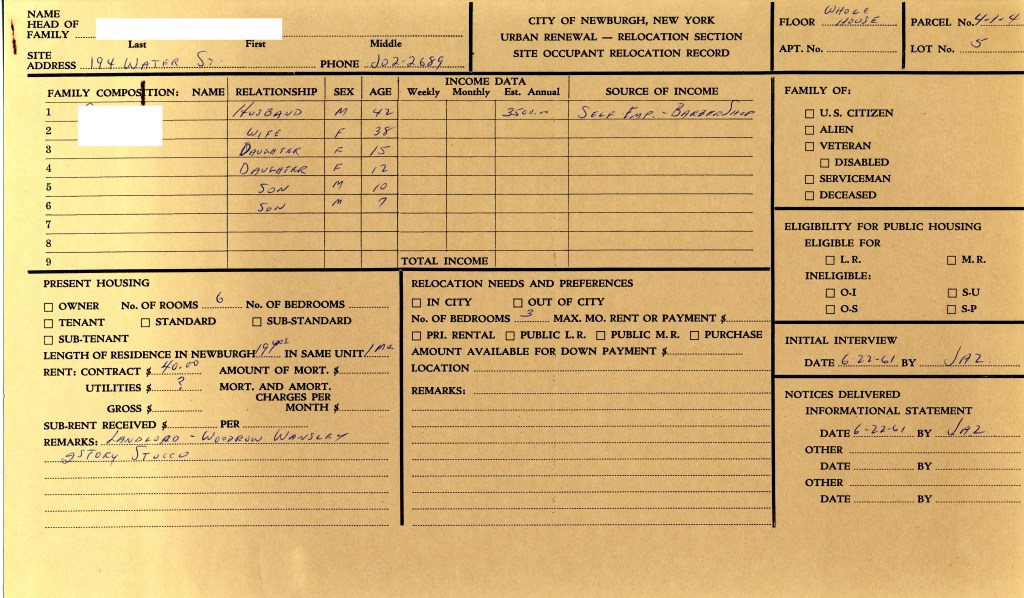

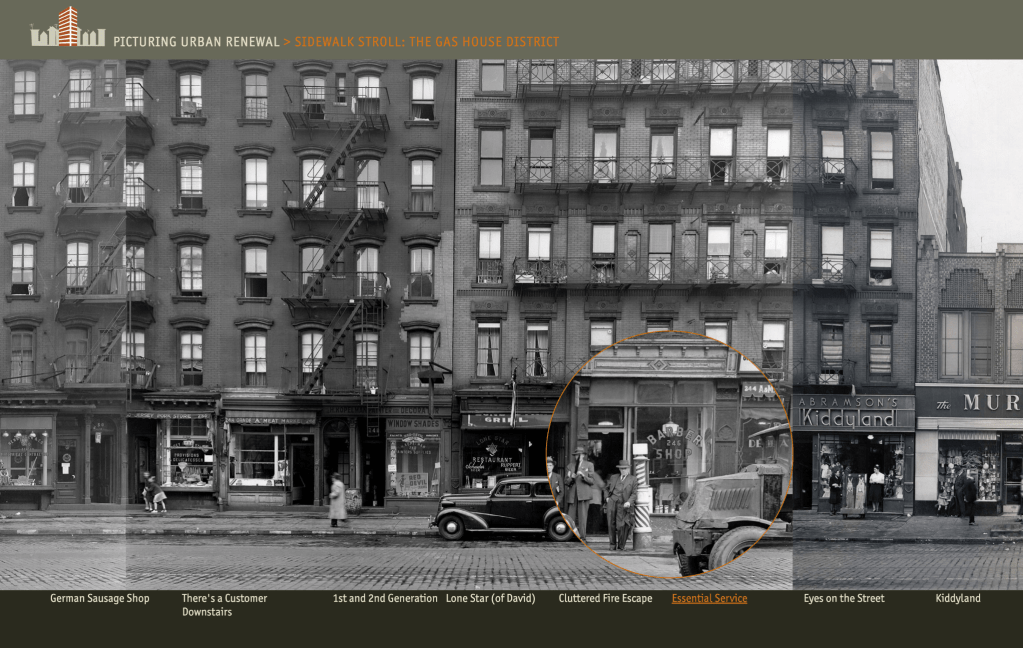

Photographs offer a different and more intimate perspective on urban renewal. Much of our research has focused on the people most affected by urban renewal, particularly those who were displaced. Appraisal photographs, like the ones we found in Albany, facilitate the street-level reconstruction of the areas demolished for urban renewal. Stitching them together, we can reimagine these areas and the people who lived and worked there. Photographs also prompt interesting social history questions: Who is in the photograph? What can we find out about how urban renewal affected them? Where did they shop and worship? What happened to them after they moved out of their homes and businesses? These questions prompted us to conduct oral history interviews and to explore other sources, including the US Census, local newspapers, city directories, and renewal agency relocation and property acquisition files.

Why New York State? Also, you’ve identified four very different sorts of communities—Stuyvesant Town (New York City), Newburgh, Kingston, and Albany—how did you come to focus on these cities and how do they combine to tell the story of urban renewal in New York and nationally?

New York State has an important legacy of urban renewal; it was second only to Pennsylvania in the amount of federal funding received (about $1 billion), the amount of projects started (about 300), and the number of places affected (about 90). The State encouraged municipalities to apply for federal renewal funds by committing to cover half of the local contribution required by federal regulations. Places ranging in size from villages of a few thousand residents to the state’s largest cities received renewal funds.

We focused on these four cities both because of the rich visual and documentary assets we found and because redevelopment in these four places differed significantly as to demographics, time period, and redevelopment goals and outcomes. Placing these cities side by side sets up a comparison and allows us to construct a more complete, and complicated, picture of urban renewal. This focus also sheds light on how state and federal policies responded to local conditions.

Who is the audience for Picturing Urban Renewal and how do you envision them interacting with the site?

We expect to attract a broad public audience but plan to focus our outreach efforts on educators, amateur historians and history practitioners, preservationists, urbanists, civic leaders, and engaged citizens. The website will include special sections for K-12 educators and for local historians and other stakeholders interested in researching urban renewal in their communities. We also plan to launch a Substack newsletter in Summer 2023 to publicize interesting research finds and to stimulate interest in Picturing Urban Renewal.

Has working on Picturing Urban Renewal changed your perceptions of urban renewal or has it reinforced earlier views? Or perhaps a bit of both?

A bit of both. Going in, we were aware that most municipalities developed renewal plans to combat the effects of economic and racial segregation but ended up reinforcing, even deepening, those divisions. Urban renewal destroyed the very places the policy was meant to improve. It exacerbated racial tensions, reduced tax bases, demolished historic communities, and created traumatic stress, what psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove calls “root shock.”

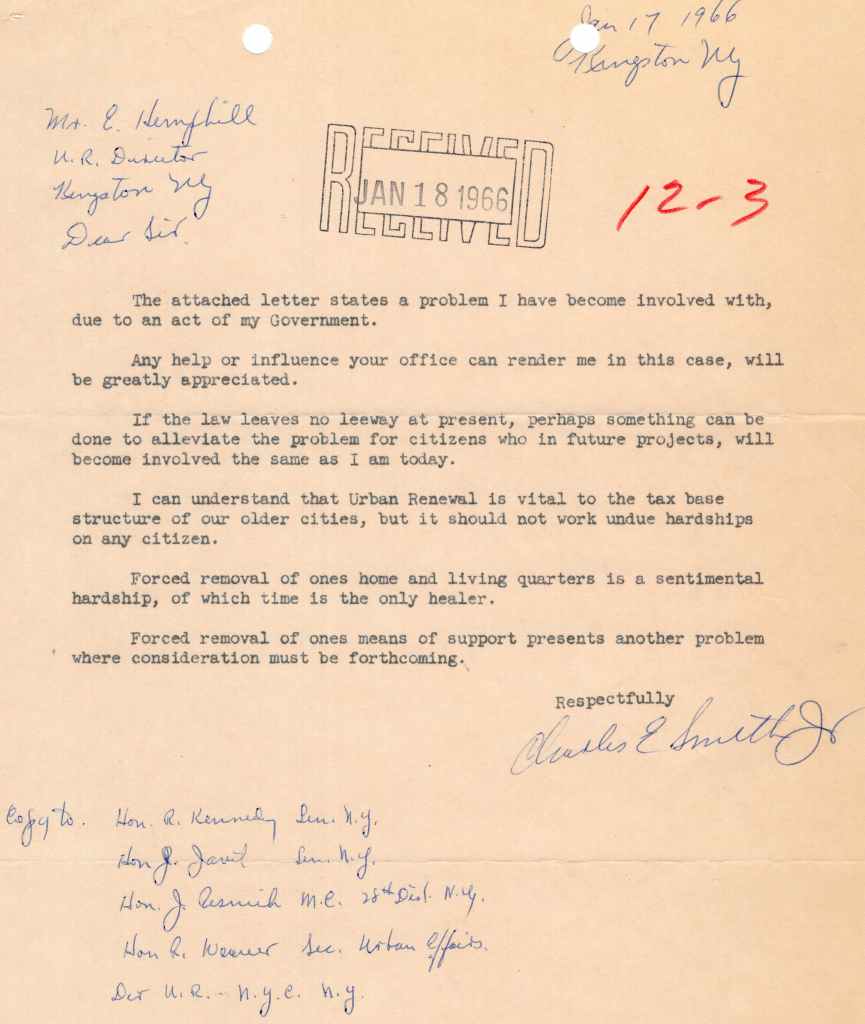

We also learned that people experienced urban renewal in different ways. For example, some area residents, particularly owners whose property was seized after passage of the Housing Act of 1968, benefited (at least economically) from urban renewal. Similarly, we learned that federal policymakers were aware early on of the inequities and disruptions caused by urban renewal, but acted only belatedly in the late 1960s and early 1970s to mitigate them. Finally, some of the most damaging effects were experienced by people who lived just outside of the renewal areas.

What have been the project’s most significant challenges, and how have you engaged them?

The main challenge we’ve faced is how to develop a narrative strategy that integrates different types of sources: planning maps and photographs, archival documents, and personal recollections. This is something that historians (digital or not) in general face, so we’re not unique here. More specific to our project is the unevenness of the available archival collections, particularly when it comes to images. In the case of Albany, for example, we found several hundred compelling photographs of building interiors and the people inside them, but we’ve been unable to locate residential relocation files that could tell us more about the 7,000 people displaced. In contrast, Kingston appraisal photographs preserve only building exteriors, but the relevant acquisition and relocation records are rich. They contain detailed information about displaced residents and a series of “hardship letters” addressed by property owners to local officials.

Where do you situate Picturing Urban Renewal in the general sphere of digital humanities? What is the future for digital humanities more generally?

Digital humanities is, in many ways, like the parable of the blind men and the elephant. It’s different things to different practitioners—social network analysis, GIS data visualizations, text mining, etc. Our focus is, and has been since the beginning, on visual storytelling and presenting visitors with the opportunity to evaluate some of our sources.

What has struck us is that in the past decade or so, the learning curve for entering the digital humanities space has become more surmountable. We started off without any coding experience–Tweeting, posting on Facebook, blogging on WordPress. We added a Knight Lab Timeline and StoryMap to the blog after a THATCamp session. And there are a lot of other free or inexpensive, off-the-shelf options out there—Omeka, Curatescape, ArcGIS. Particularly for those of us who hope to engage with public audiences, digital methods are key.

Additional Digital Summer School 2023 (DSS 2023) Entries:

- DSS 2023: The Valley of the Shadow 2.0

- DSS 2023: Scioto Historical

- DSS 2023: Building the Black Press

The Picturing Urban Renewal team are David Hochfelder, Ann Pfau, Stacy Sewell, Don Button, and Juliet Jacobson. Hochfelder is associate professor of History at University at Albany, SUNY. Pfau is an independent scholar in Albany, NY. Sewell is professor of History at St. Thomas Aquinas College. Button and Jacobson are principals at web development firm DigitalGizmo.