By Amanda Page

When I’m asked to offer an example of digital humanities, I point directly to the Scioto Historical website and app. It is a repository of much historical information about Portsmouth, Ohio, and Scioto County—of which the city is the seat. The county is home to approximately 73,000 people, and Portsmouth can claim 20,000 of that number. At its height, Portsmouth’s population rose to almost 30,000, but declined with the loss of industry in the city and surrounding counties. While able to hold on to its status as a city, it still meets all qualifications to be classified as “rural” for economic development grant application purposes. It maintains an urban feel to some degree. Preservation efforts have been made in recent years to keep part of the downtown intact. A college campus sits one block away from the main business district, yet it never became a stretch where students spent time. The city struggles with its urban future, but has access to a strong grasp of its past through the Scioto Historical app.

Developed by Dr. Andrew Feight, professor of history and director of the Center for Public History at Shawnee State University, Scioto Historical serves an important role in the community. Although there is a local history department at the public library, a historical society that focuses on one house and time period, and one county heritage museum that has yet to find a home, the Scioto Historical app and website provides a unified location where people can find information about local history, as well as guidance on how to tour important locations. Beyond its importance to Scioto County, the app and website serve as an example of how humanities can have an impactful digital presence.

I asked Dr. Feight about the origins of Scioto Historical, its intentions and goals, and the overall impact it has as an example of Digital Humanities.

AP: How did the idea for Scioto Historical come about?

AF: Back in June of 2007, I launched what I called the Lower Scioto Blog to share my local historical research and photography with the wider public. At the time, I was an assistant professor of history at Shawnee State University, with a heavy teaching load. I was slowly working on a book project, with a working title of The Lower Scioto Valley in the Early Republic. The blog allowed me to share conference papers and other snippets of my research, which I imagined were to be building blocks from which I would construct the book. Coincidentally, June 2007 also marked the release of the first generation of iPhones.

By 2011 the smartphone revolution was fully underway, and it was clear to me that the future of history was going to be digital and mobile. That fall, while developing a sabbatical proposal, I connected with Mark Souther and Mark Tebeau, the developers of the Curatescape software, at Cleveland State University’s Center for Public History + Digital Humanities. Their pioneering Cleveland Historical mobile app demonstrated the potential for what I’ve come to call “geo-located” or “place-based” storytelling.

By outsourcing the software programming and app design to the folks developing Curatescape, I was able to concentrate on content development.

AP: When did you start drafting the first content?

AF: While some posts from the Lower Scioto Blog were recycled and incorporated into the initial launch content for the Scioto Historical project, most of the Version 1.0 content was researched and written during my sabbatical in the spring and summer of 2013. The app and website officially launched in June 2013, taking nearly two years for development.

AP: Was it always going to be a mobile app? Why or why not?

AF: Nope. See above. You could say it started out as a book project, became a mobile app and website project, and in the future I imagine it will ultimately lead to a book and other more focused documentary projects.

AP: How was it originally funded? How is it typically funded now?

AF: The initial development was funded via my sabbatical, with additional support from the Shawnee State University Development Foundation and the Scioto Foundation, two local non-profits. Additionally, through classroom adoption at Shawnee State University, with students contributing to the research and beta testing of new features, we are able to apply student course fees toward the software licensing and web hosting costs associated with the Scioto Historical Project. Thus, annual maintenance costs are funded via student course fees, while major content updates, such as our recent Version 4.0, was funded by another sabbatical and a $20,000 Media Grant from Ohio Humanities.

The Center for Public History recently received a three-year POWER Grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission, which is funding a nine-county research program into the history of the Underground Railroad in the Ohio-Kentucky-West Virginia tri-state region. This work will lead to the listing of twenty-seven locations on the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom and will serve as the basis for a future update of Scioto Historical’s Underground Railroad content.

AP: Who writes Scioto Historical? Who decides on its content?

AF: As the director and editor of Scioto Historical, final editorial decisions rest with me. While I have authored much of the content (both text and documentary photography), we do work with other historians, authors, photographers, and artists. We encourage submissions, and as an editor, I’m happy to work with authors on new story entries and tours. For example, we are currently working with a specialist in the Jewish history of Ohio and anticipate launching a new driving and virtual tour that explores Portsmouth’s own Jewish history, with stops at the former locations of their place of worship and the Hebrew section of Greenlawn Cemetery that dates back to the mid-1800s.

AP: And how is that content sourced?

AF: Each entry in the project includes a list of sources, ranging from original primary sources to the latest scholarship on a topic. Beyond that, we work to illustrate our stories with original documentary photography, as well as historical images from area archives, including original images reproduced from newspapers and other photographic records in the Center’s archives, along with photographs and postcard images from the collections of the Scioto County Public Library’s Local History Department and the Ackerman Collection at the Southern Ohio Museum and Cultural Center. For the Version 4.0 update, we commissioned documentary photography by Vaughn Wascovich, who has spent the last twenty years documenting river towns in the Upper Ohio Valley, and we commissioned digital simulations of the Portsmouth Earthworks Complex by Herb Roe, a native of Portsmouth who is known for his 3D-visualizations of prehistoric North American ceremonial and village sites. Herb and I have been collaborating since Version 1.0, when the Scioto Foundation funded six original oil paintings by Roe, including a portrait of Robert Dafford, the painter of the flood wall murals.

AP: Who is the intended audience?

AF: Ultimately, as a public history project, our intended audience is the general public, but more specifically it is aimed at two distinct public audiences: 1) local high school and college students and scholars who have an interest in the region’s history; and 2) cultural heritage tourists and local history buffs that enjoy visiting and touring sites that connect local history to the larger narrative of American history.

AP: How is the app promoted?

AF: The app has been promoted through the distribution of rack cards, with a QR code directing users to the project website. These cards are available at the Scioto County Welcome Center and other locations in Portsmouth. The release of Version 4.0 this past fall was accompanied by six public events, which included demonstrations of new walking and driving tours. Additionally, I regularly promote the project at invited talks before Rotary, Kiwanis, and other local groups. With funding from Ohio Humanities, as part of our promotional efforts, we worked with Brian Richards and Darren Baker at Bloody Twin Press, a local outfit whose print shop is located on a ridge top, on a small in-holding, deep in Shawnee State Forest. These limited edition prints, one for each of the six new tours, were designed by the project team to look like the front page of a nineteenth-century newspaper. They are meant to be placed in a store shop window, for example, or framed for display, and each one includes its own map and tour description. These will soon be available online as a fundraiser for the further development of the project.

AP: How have you typically measured the success of Scioto Historical?

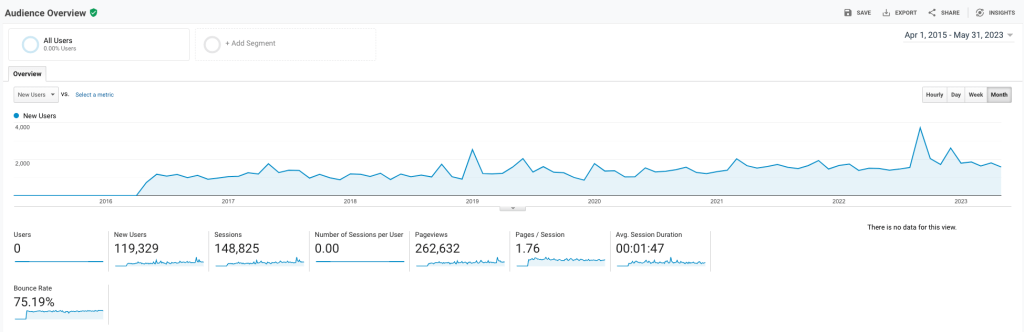

AF: We use website and app store analytics to measure our success and the growth in use. Some of our latest data can provide a sense of the project’s reach and relative “success.”

Currently, our website sees the most traffic, averaging about 1,800 unique users per month. Over the last five months we’ve had 9,000 users, with 18,000 pageviews. Since April 2016, when we began tracking these numbers, we have reached a total of 119,000 users, with some 262,000 pageviews. That’s over a quarter million pageviews since 2016, and we first launched in June 2013! I’m pretty certain my article on the antislavery movement in the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society hasn’t been read more than a hundred times since its publication in 2004.

By the way, from the above graph, you can see the bump in users we received with the roll out of Version 4.0 in the fall of 2022. Big thanks to Ohio Humanities and Shawnee State University for funding that.

There are other measurements of success, which are not so easily quantifiable, but nonetheless demonstrate the importance of local public history projects. Here are a few examples of how the Scioto Historical project has helped support historical preservation efforts. First, our research and published accounts of the history of segregated Civilian Conservation Corps camps and their contribution to the construction of Shawnee State Park and Forest led to the construction of a memorial, with interpretative signage, at Roosevelt Lake. Our research led the Ohio Department of Transportation and the Ohio State Historic Preservation Office to conclude that a historic bridge in the park was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. This determination triggered a process under the National Historic Preservation Act that required mitigation for the demolition of the CCC-built bridge. That’s how the stone memorial and interpretative signage came to be built.

Our work on the history of Portsmouth’s Eugene McKinley Memorial Pool, and its tragic connection to racial segregation, helped secure the site’s listing as a Civil Rights Movement historical site in the National Register of Historic Places. Additionally, the Scioto Historical Project’s work on the Underground Railroad paved the way for our current grant from the ARC and helped spark plans for a new Underground Railroad flood wall mural, which will highlight the central role that African American residents of Portsmouth and Scioto County played in the operations of the Underground Railroad.

AP: What role or purpose do you see the app fulfilling in the local history ecosystem in Portsmouth?

AF: In a way, one can see the Scioto Historical Project as a virtual, online museum, with historical and current documentary image galleries, short videos, and occasional audio recordings (snippets from oral history interviews, for example). The mobile app version is meant to make all this content available “in the field” and “in the palm of your hand,” through virtual historical markers that turn the landscape into a museum, with curated tours that explore different time periods and topics of local history. The content is supported with research in the archives and collections of local cultural institutions, including those collections being built at SSU’s Center for Public History. The vision is for the Scioto Historical Project to be the premier online and mobile historical platform for those interested in learning about the city and region. My hope, for example, is that Scioto Historical users will learn about the prehistoric Native American artifact exhibition at the Southern Ohio Museum while using the app or website and then they will decide to visit the museum in person.

I also intend for Scioto Historical to help diversify the public history of Portsmouth, highlighting the rich Black history of the community, something that has been historically and institutionally neglected. There is a great need in Portsmouth and other Appalachian communities to diversify their archival collections, which have their origins in a time of racial segregation in the twentieth century. My hope is that by building collections and creating a more inclusive and accessible public history, we can more fully capture the diversity of Portsmouth’s past, present, and its future.

Like many smaller American cities, particularly those that have experienced a significant population decline over the last fifty years, Portsmouth’s cultural heritage institutions were established in a different era, when there were twice as many residents from which to draw financial support and volunteer hours. The Local History Department at the Public Library and the Ackerman Photography Collection at the Southern Ohio Museum and Cultural Center are key repositories and archives, yet these collections are not the sole focus of either of these institutions. The Library still acquires items and has made great strides towards digitizing its local history collections, but it is running out of room and has restrictions on accessioning physical objects, which would be more appropriate in a museum collection. Meanwhile, the Southern Ohio Museum is no longer adding to its historical photo collection and instead is focusing on its art and Native American artifact collections. For a long time, it has been clear that there is a need for another photographic archive, and that is something that the SSU Center for Public History has been working to develop. For example, we recently accessioned the Billy Graham Photography Collection—over 10,000 negatives by the famed Portsmouth Daily Times photographer from the 1950s through the 1970s. Digitization is set to begin this fall.

There is a nominal, county-wide historical society—the Scioto County Historical Society. This nonprofit was founded in the 1960s to preserve the 1810 House; the all-volunteer organization marshals its limited resources to maintain its property as a pioneer-era house museum. Over the years, the house became the community’s attic, filling up until there was no more room for new acquisitions. Recently, local collectors of Portsmouth memorabilia and historical artifacts responded to the need for a county wide repository and history museum. Unfortunately, with the small pie of local historic preservation and cultural heritage funds, the new museum board has yet to secure a permanent location for a brick and mortar museum. Additionally, when smaller historical societies for towns like Lucasville and Otway are added to the mix, the competition for funds and the time and energy of volunteers is a serious issue, contributing to the overall struggle that each organization faces.

AP: What is the advantage or benefit of being attached to and/or hosted by a university?

AF: As a university affiliated project in a city and region that is economically distressed, the Scioto Historical Project has benefitted from institutional financial support and through the inclusion of undergraduate students in the research and project development. By partnering with the university library, we have been able to piggyback on its permanent digital repository, creating a “community archive,” where we have begun to diversify “the archive” with oral histories, digitized images, and other materials that document the African American and Latine communities in Scioto County. A university affiliation has also proven helpful in securing external grant funding, as the university can apply the value of my time spent on a project as an in-kind match, which allows for the SSU Center for Public History to apply for much larger grant awards.

AP: What are the plans for the future of Scioto Historical?

AF: We will continue to work with the folks at Cleveland State University on programing and feature updates on the software side, and we will continue to work with authors and artists who would like to contribute to the project. In addition to the new Jewish history tour, we anticipate a major update to our Underground Railroad content as we complete the ARC-funded Network to Freedom research and nominations.

AP: Scioto Historical acts as both an example of digital humanities and an example of a tool for local tourism bureaus. Does the local tourism bureau support Scioto Historical? If so, in what ways?

AF: The Scioto County Visitors Bureau has supported the project in the past through the distribution of project rack cards at their Welcome Center in Portsmouth. The Bureau recently hired a new Executive Director, and we are currently discussing ways we can work together to better promote the use of the website and mobile app.

AP: Where do you situate your project in the constellation of the digital humanities?

AF: I believe in the power of the hyper-local story to connect people with their own community’s past and their place in the larger narrative of American history. I frequently tell my students that American history happened here. As a humanities project, the aim is to gain insight into the human condition, the lived experience of our ancestors and predecessors, those who have acted out their lives on this same stage, however much the scenery and props may have changed over the decades. Today, in my mind, being digital means being mobile and, as a mobile public humanities project, the Scioto Historical Project is meant to provide access to hyper-local, trusted, curated historical knowledge that promotes a sense of community and supports historic preservation and cultural heritage tourism initiatives in the city and region.

AP: Where do you see the field going in the next few decades?

AF: Mobile applications for touring historical sites will continue to evolve, with increasing use of augmented-reality functionality, moving in the direction of virtual-reality simulations of historical sites. How artificial intelligence may change the field is unclear, but currently hyper-local historical research (often in sources that have yet to be digitized) will continue to shape the practice of public historians. Traditional historical scholarship will continue, but the turn towards undergraduate programs in applied history (what is more commonly called public history) will also continue, as employment opportunities with cultural heritage and educational institutions are expected to last into the foreseeable future.

Additional Digital Summer School 2023 (DSS 2023) Entries:

- DSS 2023: The Valley of the Shadow 2.0

- DSS 2023: Picturing Urban Renewal

- DSS 2023: Building the Black Press

Amanda Page is a Columbus-based writer from southern Ohio. Her work appears in Belt Magazine, The Daily Yonder, 100 Days in Appalachia, and other publications. She is the editor of The Columbus Anthology from Belt Publishing and The Ohio State University Press, and founder of Scioto Literary, a nonprofit that supports writers and storytellers in Scioto and surrounding counties in Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Page is co-director, with David Bernabo, of Peerless City, a documentary that examines the rise and decline of economic prosperity in Portsmouth, Ohio through the lens of three distinct slogans publicized by the city. Look for Peerless City on PBS Passport in August 2023.