The original The Valley of the Shadow website launched thirty years ago and is often cited as among the first digital humanities projects on the web. Two communities in the Great Valley, one in the North and one in the South, are documented in a database of public records, newspapers, correspondence, images, maps, and other artifacts. Instead of focusing on battles and generals, students and scholars explore personal narratives and contextualize our nation’s most troubling era. Using enhanced search features and improving accessibility and readability, its creators aim to engage a new generation of learners with an updated version 2.0 of The Valley of the Shadow. It is clear that learning how to think about history and investigate it independently continue to be overarching goals of The Valley project. Annie Evans and Ed Ayers spoke (virtually) with The Metropole to discuss the history of The Valley project, how it has been used, its connection to urban history, the numerous online projects that evolved from it at the University of Virginia and University of Richmond, and what they see in the future for digital humanities.

The original proposal by Edward L. Ayers for The Valley of the Shadow dates back to 1991; the version accessible to researchers today has been updated twice since then. How has the site changed over its 30 years of existence?

The project continually evolved even as it was being built and the capacities of the technology increased. When we began, pdf files did not exist, and few users had the computing capacity to handle the transfer of large images. By the time we completed the first edition of The Valley in 2007, smartphones possessed more computing power than earlier desktops mustered. All along, even as we upgraded coding languages and file formats, the principles remained the same: the presentation of the raw materials of history in ways that allowed them to be explored, questioned, and interpreted.

We owe a lot to the folks at the University of Virginia Library, who maintained the original site after Ed left UVA in 2007 to become president at the University of Richmond. Like many web-based projects, over time links are broken, or access to software changes as devices become more sophisticated. We took the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary to partner with our web designers at Journey Group to refresh The Valley’s visual design and empower its databases.

Within The Valley 2.0, students from diverse backgrounds may begin to see themselves in the story of America. Making the content more accessible allows students to make connections across the databases, enhancing their exploration and understanding, as they build historical empathy, pose questions, and look at history from the vantage point of multiple perspectives. They begin to see history as not just a finite set of facts to memorize for a test. More importantly, The Valley models how they may then investigate similar sources to learn how their own hometown fit into this and other time periods of history, engaging through local archives and digital tools to expand their view. We offer a more comprehensive history of the project here.

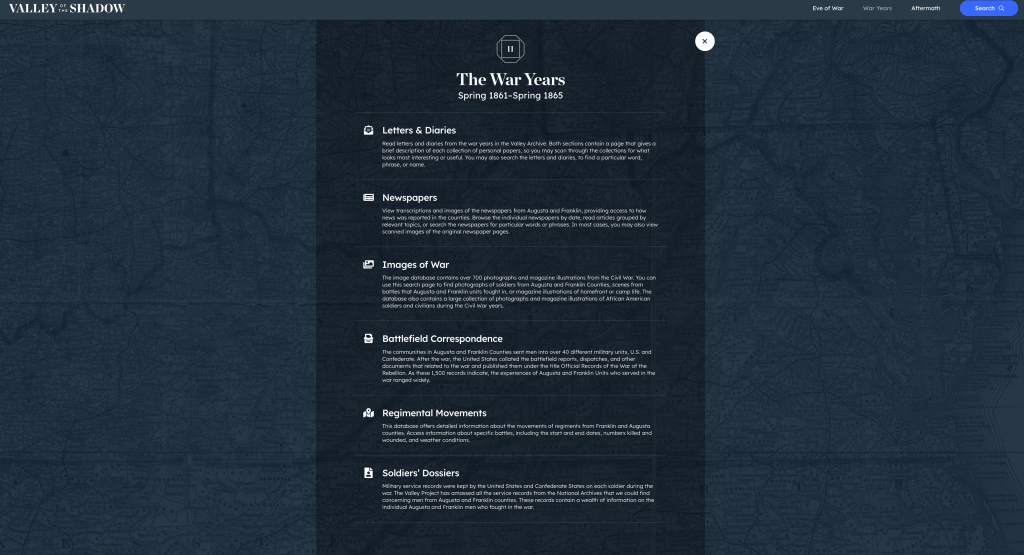

The Valley of the Shadow incorporates a diverse set of historical data to document the Civil War in Augusta County, Virginia, and Franklin County, Pennsylvania, including photographs, correspondence, newspapers, diaries, soldier’s dossiers, and census, tax, and church records, among other material. How did you and others decide on what kinds of materials to use?

At the outset, the premise was to include “every piece of information about every person” who lived in those two communities. We set up scanning events in both communities, digitizing letters, diaries, maps, images, newspapers, and public records buried in family attics and local archives. We found sources in dozens of places. The foundation of the project lay in the newspapers and census records of the two counties, which allow users to trace the story week by week and into every household. But the most powerful records turned out to be personal records that revealed the life-defining decisions of thousands of people of all kinds of backgrounds.

What have been the biggest challenges of the project?

The sheer scale of the sources and their existence in non-machine-readable form. Everything had to be typed in, including ten thousand pages of newspapers and tens of thousands of names in multiple censuses. Fortunately, we had cadres of paid students, who found the work interesting and engaging, and the leadership of William G. Thomas III and Anne Rubin, who oversaw the work on the project.

With The Valley of the Shadow 2.0, the challenge became reimagining the project for a new generation of learners with Chromebooks, iPads, and smartphones in hand. Adapting it to screens of all sizes and enhancing the search features to avoid what previous users found “clunky” was very much about modern web design. For that, we thank our collaborators at The Journey Group. We also gathered feedback from a generation of users who grew up using The Valley, including students who helped build it at UVA thirty years ago, many of whom are now K-12 history teachers or professors, librarians, and museum educators.

On its surface, The Valley of the Shadow does not seem obviously urban in its focus. Where and how does the project address urban history?

Staunton and Chambersburg were considered large towns for the era and served urban functions for large hinterlands with railroads, factories, warehouses, and stores; that’s why they were targeted by both the United States and the Confederacy. Railroads connected them economically to other urban centers, including Richmond, Baltimore, and Pittsburgh. Strategically, the Great Valley served as a key position during the war, first as Virginia’s breadbasket, providing provisions for the large armies that operated there. The Great Valley provided a major Union supply link between Washington, DC, and the western states and was a key route to the Confederate capital of Richmond, forming a natural corridor through which Union armies could penetrate deep into Virginia and threaten the city from the rear.

With such a long history, how have audiences engaged the site over the years? In what ways has this engagement aligned with expectations and diverged from it?

Between the two of us, we have the perspectives of both the producer and consumer of this content, as Ed created The Valley with students and colleagues at UVA alongside contributors from the humanities and tech communities, while Annie was a beginning teacher and early adopter of digital humanities projects and geospatial technologies in secondary classrooms in Richmond, Virginia.

For Ed, an “Aha!” moment came while he was teaching on a Fulbright scholarship in the Netherlands, when his students and Dutch colleagues discovered an early version of The Valley of the Shadow in its infancy on the World Wide Web. It turned out that those who taught American history abroad found The Valley project even more useful than perhaps his colleagues back home, for it permitted their students to do a kind of research otherwise impossible. As more people used the World Wide Web in the late 1990s, many discovered The Valley of the Shadow project. Back home, The Valley project led to the 1998 founding of The Virginia Center for Digital History, an incubator for a whole series of innovative sites on everything from Jamestown to the Civil Rights struggle.

Meanwhile, while In her third year as a US history and geography teacher, Annie struggled to help her students move beyond rote memorization of battles and generals, and the Lost Cause version of history in the adopted textbook. Long before teaming up to build New American History, she heard Ayers speak at a teacher symposium about his new digital project and convinced her principal to provide her and her students access to some surplus Apple 2e computers and funds to purchase five sets of The Valley of the Shadow CD-ROMs. This was a game changer in terms of framing the story of forced migration, secession, war, and Reconstruction while living in the shadow of the former Confederate capital. Students traced families across letters, diaries, newspaper clippings, and military records, piecing together personal narratives for soldiers, mothers, freedmen, and local leaders. They read about everyday life and made connections, past and present. They delved into their own local Richmond archives, read letters and diaries, and compared stories and experiences shared not only in Staunton and Chambersburg, but across the country. They learned the skills of navigating, searching, transcribing, and analyzing sources, looking for clues as to who wrote them, what was their intended audience, whose perspectives and stories were being told, and whose were missing.

The Valley helped frame the way they looked at every other period of history they studied and moved them away from waiting for a teacher to tell them what they needed to know or memorize to pass a test. They explored local historical sites, looking for clues and connections, past and present, on the physical and cultural landscapes in and around Richmond, based on similar observations gleaned from The Valley archives regarding Staunton, VA, and Chambersburg, PA. They created a museum of local history in the vacated A/V storage room of their school library and narrated audio tours for the local Civil War cemeteries and battlefields, with help from park rangers and their school librarian. They carried their curiosity with them to high school and college, the workforce, and later as parents of their own school-age students.

The digital divide has narrowed, in terms of access to digital tools and resources, but also in the field of digital humanities as a respected and much sought-after medium in the field of history education for learners of all ages. We are inspired by the work The Valley has and continues to model for the next generation of public historians, educators, and leaders.

The Valley of the Shadow is just one part of the larger digital humanities projects at the University of Richmond, what are some of the other projects and how do they relate to one another?

We like to think of New American History as an ecosystem—our homepage was recently reorganized to reflect this, as we thought of the way our learning resources combine and explore the intersection of journalism, multimedia, and geospatial technologies with scholarship and archives. Bunk is and archive and shared home for the web’s most interesting writing and thinking about the American past, a dynamic and multidimensional connection engine between past and present. The Digital Scholarship Lab, founded by Ed as he assumed the role of University President at UR, includes American Panorama, a digital atlas of interactive maps and visualizations of social, economic, and political forces through US history. The BackStory podcast archives and PBS series The Future of America’s Past are audio and video components of the ecosystem from our collaborations with the UVA-funded Virginia Humanities, and Field Studio. Content from both is easily accessible and intertwined along with the Panorama maps, related content as connected in Bunk, and a growing list of digital humanities collaborators working with Annie and teachers across the country to create a growing library of inquiry-based learning resources that ensures every student sees themselves in the story of American history.

Where do you situate The Valley of the Shadow and other digital humanity offerings from the University of Richmond in the growing field of digital humanities? Where do you envision digital humanities going in the next decade or so?

We see more universities and public-facing institutions contributing to the further democratization of public records, historical documents, and rich open educational resources as the field of digital humanities expands. We have seen one of our other signature collaborations and projects, Mapping Inequality, grow and expand into the fields of environmental science, public health, urban planning, and public administration.

With so much talk about the rapidly expanding field of AI, we are imagining new and more powerful ways historical content may help bring multiple perspectives into rural, urban, and suburban classrooms and communities. With this access comes greater responsibility, however, to ensure we teach students skills in data and media literacy, as well as greater accountability among our colleagues in the field to hold space for multiple perspectives in both the content and the creator, and to work to remove biases and inaccuracies and keep disinformation from flooding the web and obscuring the wealth of legitimate digital scholarship emerging exponentially.

Universities need to better recognize and reward faculty members engaging in digital scholarship, including but not limited to the field of digital humanities, including consideration for tenure. Likewise, student accessibility features must continue to be enhanced, including access to reliable internet and devices, and built-in tools for students with disabilities and English language learners.

Digital humanities at all academic levels must lean into inquiry and create pathways away from the limitations of textbooks, term papers, and standardized tests. When harnessed for good, digital humanities builds skills in critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity; skills we are sorely lacking in the current political climate. The best way to combat book banning and the noise of “divisive concepts” rhetoric is to teach children the truth about our nation’s past and provide safe spaces for them to explore, ask questions, and make meaning of how they and their communities fit into the larger historical context of our nation and our world.

Additional Digital Summer School (DSS) 2023 Entries:

Ed Ayers has been named National Professor of the Year, received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama at the White House, served as president of the Organization of American Historians, and won the Bancroft Prize for distinguished writing in American history. He served as the founding chair of the board of the American Civil War Museum. Ed is host of The Future of America’s Past, a television series that visits sites of memory and meets the people who keep those memories alive. He is the Executive Director of New American History, an online project based at the University of Richmond designed to help students and teachers to see the nation’s history in new ways. His newest book is American Visions: The United States, 1800-1860.

Annie Evans is the Director of Education and Outreach for New American History at the University of Richmond. Annie is a National Geographic Society Grosvenor Teacher Fellow, a NatGeo Certified Educator and Trainer, and Co-Coordinator of the Virginia Geographic Alliance. With over thirty years of classroom and educational leadership experience, she designs curriculum and facilitates professional learning for K-16 teachers and museum educators, focusing on historical thinking skills, geoliteracy, instructional coaching, project-based learning, and performance assessments. She hopes New American History will inspire the next generation of public historians, history educators, and civic leaders.

Featured image (at top): Collage of images from the original The Valley of the Shadow project. Image courtesy of New American History at the University of Richmond.