Fifty years ago this September, gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson sat poolside at the Watergate with a young Pat Buchanan, who, according to Thompson, was “one of the few people in the Nixon administration with a sense of humor.” The two men drank beers while gossiping about Tex Colson and discussing the nature of political relationships between ideologues. Thompson had first shared a drink with Buchanan, a bottle of Old Crowe, during the 1968 New Hampshire primary, “when Nixon was on the dim fringes of his political comeback.”[1]

Ironically, Thompson had been staying at the Watergate Hotel on the night of the break-in, just over a year earlier, swimming laps in the pool before meeting in the Watergate Bar with Washington Daily News sports writer Tom Quinn. Quinn and Thompson knocked backed Sauza Golds with limes and salt, “muttering darkly about the fate of Duane Thomas and the pigs who run the National Football League,” while G. Gordon Liddy, Howard Hunt, and the rest of the White House Plumbers attempted to ransack the Democratic National Committee Headquarters.[2]

The break-in and subsequent scandal defined the complex for years afterward; in fact, Thompson’s byline precedes the famous Saturday Night Massacre by less than a month. With the recent completion of the HBO series White House Plumbers and last year’s Martha Mitchell themed show, Gaslit, it’s worth taking a moment to see just how the Watergate came to be, what it meant to Washington in its first decade of existence, and how the scandal affected its fortunes.

The Beginning

In 1946, the Washington Gas and Light Company (WGLC) was looking to get rid of its “West Station Works.” WGLC had made the transition to natural gas, so coal and the conversion facility were no longer needed. The six-and-a-half-acre parcel, bounded by the Potomac River and Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, was eventually sold for $3.75 million to the largest real estate development company in Italy, Societa General Immobiliare (SGI). SGI had been around since the nineteenth century and had recently made a name for itself working on the 1960 Olympics in Rome, where it had built the Olympic Village. It had also partnered with Hilton Hotels to build the Cavalieri Hilton, overlooking the Vatican.[3]

From a development standpoint, the Watergate was the first project constructed under Washington’s Article 75 provision, which was described as an “innovative zoning ordinance designed to encourage urban redevelopment in general and combined living/commercial areas in particular,” by New York Times journalist Sherwood Kohl in 1972. In other words, the Watergate served as DC’s first mixed-used development, an encapsulation of the law’s intent to create “places that would interact with the city but take the agony out of urban living.”[4]

Even before its construction, the complex’s design encountered resistance. Italian architect Luigi Morretti, an influential modernist, designed the Watergate complex. Moretti believed Washington DC’s architecture was “too conformist,” and purposely sought to bring “a touch of Rome” to the capital. When he presented a revised set of plans to the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) in October 1963, he noted that the Watergate symbolized “where the utilitarian part of the city ends and where the romantic part starts.”[5]

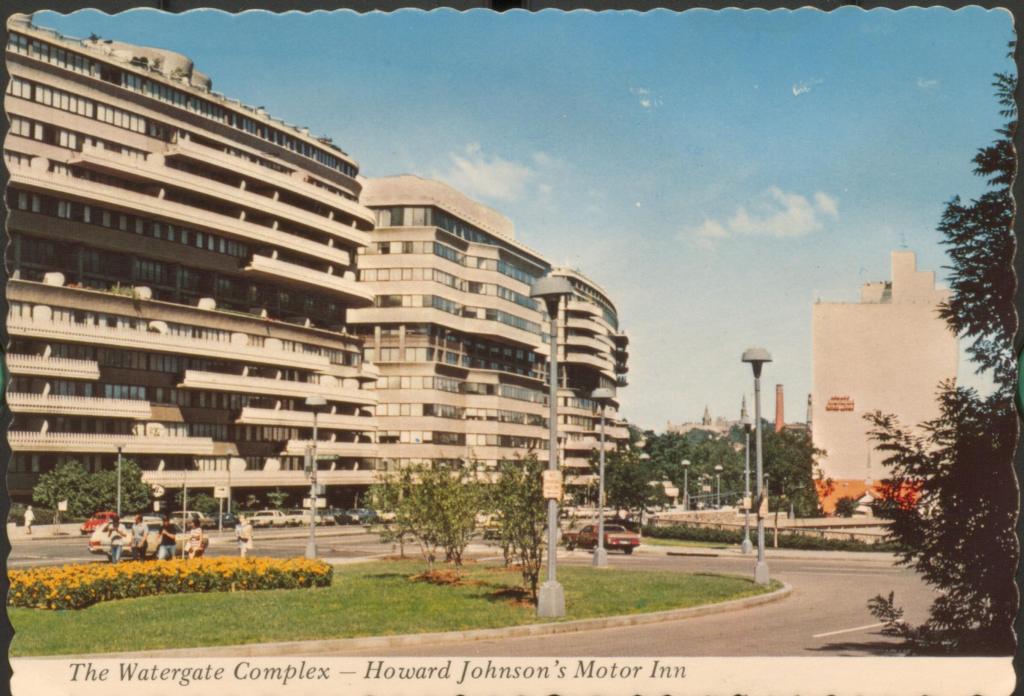

Moretti’s design features multiple curvilinear structures, along with gardens and pools designed by Boris Timchenko and situated in a concave space. The rows of balconies across the hotel and co-op structures create a striking visual; viewed from a distance they read as stripes across the building. The Watergate also features numerous panels running up the balcony walls that give it a “toothy” appearance; as one critic argued, the balusters which create this design also make the compound appear to be “buildings of broken zippers.”[6]

Many observers worried about the project’s continuity with and relationship to the then forthcoming Kennedy Center (referred to as the National Cultural Center before late January of 1964). The original design by Edward Durell Stone was “a curved, concrete and glass structure, resembling a large clamshell facing the Potomac,” notes historian Joseph Rodota.[7] Moretti designed the Watergate in relationship to these early plans for the Kennedy Center, but in 1962 Stone redrafted his design at the request of Roger L. Stevens, the new head of the board of trustees of the National Cultural Center (appointed 1961), who thought the price tag was too high for the original design. Stone’s new design was a “streamlined, rectangular structure housing a 1,200-seat theater, a 275-seat symphony hall, and a 250-seat opera house, all under one roof.”

Moretti had also redrafted his original designs to better harmonize his original plans with three features of the city: “Its monumental area defined by the National Mall and the Lincoln Memorial, the downtown business district, and the waterfront.”[8] Wolf Von Eckardt, architectural critic for the Washington Post, remarked that the Watergate plans “woefully crowd[ed] in” the future Kennedy Center. “The southernmost, massive, sausage-like building of this wiggly complex…encroaches to within 300 feet upon what is to be a national shrine. The dignity of the John F. Kennedy Center demands more land, air around it.”[9] The public, too, offered its opinion, by the thousands. By the end of January 1963, the White House had received over 3,000 letters opposing the development. Some residents even wrote the Pope, since the Vatican owned a portion of SGI.[10]

In the end, after much wrangling with the CFA and the National Planning Commission (NPC), the Watergate design was shifted to give the Kennedy Center more space, and the complex’s height was reduced to 140 feet. Construction of the Kennedy Center began the same year that the Watergate East opened, 1965, though by 1972, folks still drew distinctions between the two complexes, describing the Kennedy Center as the box in which the Watergate had been delivered.[11]

Still, the Watergate’s general architectural thrust certainly distinguished it from its peers. In addition to the Italian and Asian features often highlighted in newspaper accounts, critics of the project pointed pejoratively to the exuberant architecture of South Florida. CFA member Burnham Kelly bemoaned the proposed design and its art deco influences. “I’d like them to realize we would really blow the whistle on Miami Beach come to Washington.”[12] The Miami comparison stuck. Writing nearly a decade after Burnham’s comments, Kohl made a similar observation, noting the complex’s architectural design would be singular almost anywhere in the United States except Miami, and in federal Washington “where most edifices tend toward variations on the Parthenon theme, it is positively unique.”[13]

The Watergate East

In 1973, the development of the Watergate Complex was only just completed. Even its earliest building, The Watergate East, the first of three residential buildings (Watergate West and Watergate South being the other two, with the latter divided between residential and office space), had only opened less than a decade earlier, in 1965. The Watergate West opened in 1969, and the Watergate South two years later. The hotel and office building opened in 1967, and the Watergate Office Building in 1971.

In late October of 1965, a black-tie celebration was held for the opening of the Watergate East. According to the Washington Post, nearly 1,500 attended the event, which featured an “all-girl chamber music quartet” that “played while guests milled about.”[14] Just a few months earlier, the complex’s management made a model apartment available to potential residents. Arturo Pini di San Miniato, president of the National Society of Interior Designers, outfitted the unit with a blue and gold color motif, a mix of “Oriental Opulence and Italian Grandeur,” the Washington Post headline announced, which conveyed the “feeling for…elegance one might expect from a compatriot of Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Andrea Palladio.[15]

Throughout its existence, the Watergate’s image frequently failed to live up to reality. Though its owners sold it as luxury living, and in part this was true, it was also rife with maintenance problems. Watergate East residents formed the eleven-member “Committee on Latent Defects” to battle the buildings numerous issues, while Watergate West residents filed a lawsuit in United States District Court over similar issues, such as defective kitchen appliances in 45 percent of the apartments, inadequate air conditioning in nearly three fourths of the units, rain and water damage in 40 percent of the apartments, and nearly a quarter of the apartments suffering from plumbing issues.[16]

If one believes the diary of Katie Louchheim, deputy assistant secretary of state and member of Lady Bird Johnson’s Committee for a More Beautiful Washington, who attended the opening, it was anything but lux. Admittedly, Louchheim, who was married to Walter C. Louchheim, was not an ideal candidate for celebrating the Watergate’s opening or praising its architectural bonafides. Walter had long opposed the complex’s construction as a member of the NPC, a point Katie noted: “Watergate, you will recall, is what is locally known as Vatican City, and no greater bone of contention ever stuck in the throat of planners like Walter C. Louchheim.”[17] And, like Walter, she thought little of its design. “The enormous pile of raw oatmeal stucco looks like a pre-historic monster, complete with dragon’s teeth that rim the occasional balconies.”[18]

The entire scene at the event carried an air of staged ridiculousness. Flower banks were “ostentatiously grouped everywhere.” The crowd consisted largely of “hanger-ons” and “moving people, all of whom looked vaguely like extras hired for the occasion, and uncertain of their non-camera directions.” The all-girl chamber orchestra sat almost as an “island in a huge sea of shouting people drinking their second drink, and in between there were bars and bars.”[19] Louchheim even wondered if the event was little more than paid publicity, especially since coverage in the local newspapers the following day proved sparse at best. ““If WATERGATE APTS were mentioned, it was in small type. I presume Rome was plastered with the pictures taken, all of us bowing to one another.” [20] In the end, Louchheim and the others went “thru [the] motions. The noise of voices rolled over us like drums. Leonard thru away his text. I had none but threw away my words.” [21]

The Louchheims were not alone in their criticism of the complex. Von Eckardt disapproved of the complex’s general aesthetic, comparing it to “a strip dancer performing at your grandmother’s funeral” and suggesting it represented the “last gasp of art nouveau…”[22] Watergate resident and GOP star Martha Mitchell complained that the appliances and accoutrements provided by the complex were for “low income” folks.

Still, the Watergate also had its defenders. Washington Post writer John B. Willmann described the view as “superb” and compared the building’s lines to a “Sandy Koufax slider.” In fact, Willmann suggested visitors stop by “just to take a squint at the hollow-through lobby entrance at night. Gives you that continental feeling. Fountains splashing water from level to level, curving stairways…and a big sky and skyline overhead.”[23] Even in his snarky criticism, Kohl, drawing upon the Italian motif, acknowledged the complex’s liveliness. “There does seem to be a Marienbad, ‘La Dolce Vita’ quality about the place, a feeling that is heightened by the labyrinthine design; by the sunken walkways, tiered fountains, striated arcs and captive gardens; a Villa d’Este turned to stone, the Andrea Doria’s superstructure cast in concrete.”[24]

Republican Bastille

The Watergate’s opening preceded the Nixon administration by three years, but his presidency ushered in the “Republican Bastille” era, as the Post put it, of the complex. Many who worked in or adjacent to the Nixon administration ended up residing in the Watergate at one time or another, including Patrick Buchanan, Bob Dole, Arthur Burns, Maurice Stans, Rose Mary Woods, John Volpe, and John and Martha Mitchell, among others. Democrats, including Senators Abe Ribicoff and Jacob Javitts, also lived in the complex, but Nixon officials proliferated.

Yet, just a year earlier in July 1967, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) established its headquarters in the office building abutting the Watergate Hotel. The DNC’s new luxury digs made some uncomfortable; Thurgood Marshall commented, “Nothing’s too good for the party of the people.” “The music is soft and piped,” noted the Miami Herald. “The girls looked like they escaped from a James Bond movie. There’s a great view of the Potomac too. Real or contrived, happiness pervades the sixth-floor, ultra-modern suite.” To be fair, the new DNC HQ had 20 percent more floor space, from 5,000 to 6,000 feet, and cost $100 dollars less at $7,000 per month, than its previous location.[25] If Katie Louchheim attended the opening, she kept her acid thoughts off the pages of her journal. The presence of the DNC and the accumulation of Nixon officials in the Watergate probably seemed appropriate contextually and added to its aura.

One need not reprise the events of June 16 and 17, 1972, except to say that the bungled break-in by Howard Hunt, G. Gordon Liddy, Alfred Baldwin, and five Cuban burglars altered national trajectories, including that of the Watergate. Visitors to the hotel stole anything with the Watergate name or insignia. The hotel stopped featuring its name on towels and the like due to such theft. The New York Times published “The Watergate Tour,” which included a map with various stops: at 2600 Virginia Avenue, the DNC, and the complex’s liquor store. Glass-roofed tour buses meandered past, replete with gawking tourists who sometimes posed for photographs in front of the Watergate sign. Some folks even took up positions at the Howard Johnson’s across the street and reenacted the events of June 17, as when one NBC Capitol Hill correspondent noticed a woman across the street watching her with binoculars. Less than a year after the break-in, the DNC moved out.[26]

For the rest of the decade, the Watergate complex remained chained to the scandal. According to Rodota, not until the 1980s and Ronald Reagan’s first term was the complex able to begin to shed its image, as Reagan officials brought a Southern California glamour to the complex that enabled the Watergate to rebrand itself, though even then, tourists still showed up now and then to take photos. A 1982 Town and Country spread encapsulated the Watergate’s departure from the 1970s with the headline: “Watergate: A Washington Nest for High Flyers.” By then, the Watergate had shed its architectural awkwardness, or perhaps, Washingtonians had shed their pretensions about its architecture. “An architectural landmark of Washington’s cityscape as familiar as the Capitol dome and the fountains of the White House,” related Mickey Palmer, “its riverside mooring carries with it an exclusivity that’s as ultimate a status symbol as the capital city offers.”[27]

Some of this newfound appreciation may have stemmed from the simple passage of time and changing tastes. For example, in Historic Capital, historian Cameron Logan discusses how urban renewal projects in Southwest DC, once disparaged for their adoption of mid-century modern style, came to be seen as historically valuable and worth preserving.[28] A similar transformation took place regarding the Watergate, though it also helped that throughout its existence the complex has had no shortage of influential tenants.

If at one time it had been associated with a political party, by the 1980s and 1990s, it was seen as a more neutral space, mostly due to the fact that officials from Democratic and Republican administrations often resided there. During their 1973 conversation, Buchanan had intimated that he got along better with fellow ideologues, despite political differences. Scandal hardly remains the purview of one party; rather, it embraces ideologies of all stripes. Perhaps this is best illustrated by the fact that Bob Dole had moved into the Watergate South during the early 1970s; by the 1990s, his nextdoor neighbor was Monica Lewinsky. After the Clinton impeachment, Lewinsky, who lived with her mother at the time, moved out and Dole purchased the unit in order to expand his own. Dole, head of the Republican National Committee at the time, had vigorously defended the Nixon administration during the controversy in the 1970s, so it seems oddly fitting and appropriate that he purchased the Lewinsky unit. From right to left, the Watergate’s scandals contained political multitudes.

In 2005 all the doubters were served their comeuppance when the complex was declared a historic landmark, following a push by local residents and preservation experts. Renowned architectural historian Richard Longstreth argued the “Watergate…stands alone—not just in Washington but in North America…really one-of-a-kind in the United States.” The DC Preservation League described the Watergate as “an exceptional example of modern era design in Washington DC” It established a new form in the city with a spatiality “more on the scale of an urban square, rather than an immense no-man’s lands of Corbusier.” The scandal added an extra layer, or what the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites characterized as a “significant, and probably transcendently important event.” Though perhaps not quantifiable, or even provable, architectural expert Emily Eig put it best after the complex achieved historic status: “The Watergate made peace with its own history…and Washington made peace with the Watergate.” [29]

Featured Image (at top): Aerial view of the Watergate Complex, Carol M. Highsmith, (ca. 1980-2006), Carol M. Highsmith Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Hunter S. Thompson, “Fear and Loathing at the Watergate: Mr. Nixon Has Cashed His Check,” in Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone, ed. Jann S. Werner, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012) 275, 283, 284.

[2] Thompson, “Fear and Loathing at the Watergate,” 281.

[3] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address (New York: Harper Collins, 2018), 9-12.

[4] Sherwood Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times, October 15, 1972; Rachel Wallace, “6 Things Gaslit Fans May Not Know About the Building Where the Watergate Scandal Happened,” Architectural Digest, June 16, 2022, https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/the-building-where-the-watergate-scandal-happened.

[5] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 42-44.

[6] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 42-44; Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[7] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 15.

[8] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 42-43.

[9] Garett M. Graff, Watergate: A New History (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2022), 160 (see footnote).

[10] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 42-43.

[11] Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[12] Joseph Rodota, The Watergate, 43; Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[13] Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[14] “The View of the Capital Was Indoors,” Washington Post, October 29, 1965.

[15] “The View of the Capital Was Indoors,” Washington Post, October 29, 1965.

[16] Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[17] Katie Louchheim, diary entry, October 27, 1965, 51-2, Box 79, Kathleen S. Louchheim Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[18] Katie Louchheim, diary entry, October 27, 1965.

[19] Katie Louchheim, diary entry, October 27, 1965.

[20] Katie Louchheim, diary entry, October 27, 1965.

[21] Katie Louchheim, diary entry, October 27, 1965.

[22] Graff, Watergate, 160; Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[23] John B. Willmann, “The State of Real Estate and Building,” Washington Post, November 6, 1965.

[24] Kohl, “The Watergate Is a World Unto Itself,” New York Times.

[25] Rodota, The Watergate, 73-74.

[26] Rodota, The Watergate, 156-157, 160.

[27] Rodota, The Watergate, 256.

[28] Cameron Logan, Historic Capital: Preservation, Race, and Real Estate in Washington, DC (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

[29] Rodota, The Watergate, 335-336.