By J. Mark Souther

On a crisp October day in 1970, a crowd cheered Carl Stokes on as he scrambled down the dock behind Fagan’s Beacon House in his yellow fishermen’s boots onto a submerged platform and sloshed through the murky waters of the Cuyahoga River. Stokes, elected 50 years ago next month as the first African American mayor of a large U.S. city, had promised this stunt of appearing to walk on water as a demonstration of his faith in the fledgling entertainment district that had recently sprung up along the riverbank. Stokes’s messianic gesture was part of the Flats Fun Festival, an event intended to help Clevelanders reframe their perception of a river that infamously caught fire the previous year.

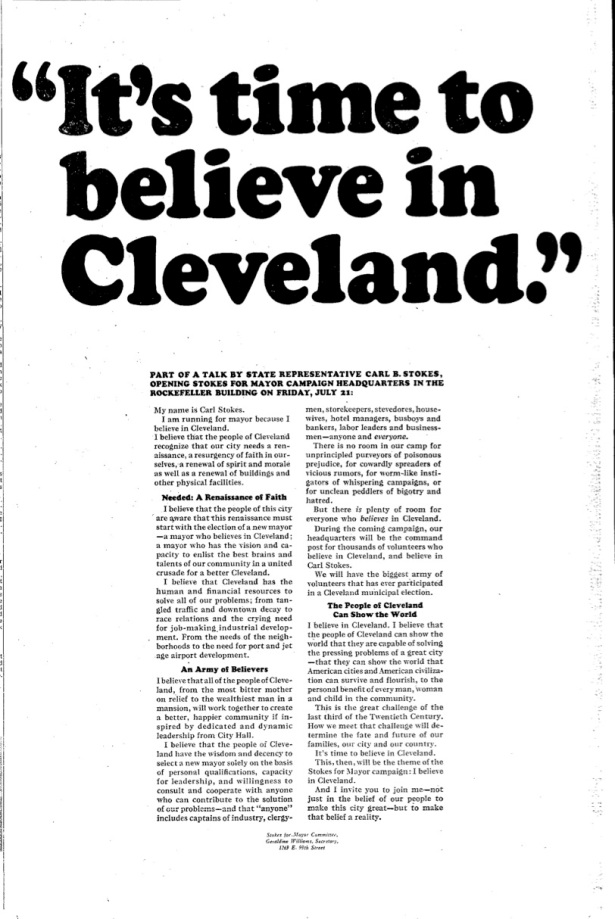

The savvy and charismatic Mayor Stokes was accustomed to embodying hope in Cleveland, a city that like many in the emerging Rust Belt was well aware of its own urban crisis before the river burned. Two race riots—the Hough uprising in 1966 and the “Glenville shootout” two summers later—had brought it into sharp focus. The city’s mishandling of urban renewal had even resulted in a federal freeze on releasing additional renewal funds to Cleveland until a few months into Stokes’s first term. Morale had sunk so low in 1967 that Stokes chose as his campaign slogan “I Believe in Cleveland” and promised a clear departure from the inertia of the “caretaker mayors” who preceded him.

The 1967 election produced jubilation. Like other energetic mayors of his time—New York’s John Lindsay, Detroit’s Jerome Cavanaugh, and Boston’s Kevin White—Stokes seemed capable of delivering a renaissance in Cleveland. He gave Clevelanders “a psychological lift” and, in the words of one observer, “a feeling . . . that perhaps the city can be saved after all.” And the hopeful image extended far and wide. The mayor’s executive assistant reported that wherever he traveled, “people were saying nice things about Cleveland again.”

The success that Stokes had in reshaping public impressions of Cleveland owed in no small measure to William Silverman, a public relations guru who had cut his teeth on Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign. It was Silverman’s idea to brand the mayor’s agenda with a catchy name to wrap its many initiatives in a shiny package. Silverman’s conception, Cleveland: NOW!, soon became a tagline for TV ads, billboards, and was an ingenious way for Stokes to cultivate the appearance of progress through otherwise unrelated modest initiatives that were more readily achieved than his more expansive plans. The symbolism of Cleveland: NOW! was useful not only for countering the enervating effect of intractable problems but also for offsetting symbolic losses that paralleled the urban crisis. Among these losses were the closures in 1968 and 1969 of the beloved Sterling Lindner department store, shuttering of the row of cinema palaces that comprised Playhouse Square, and demise of Euclid Beach, Cleveland’s most storied amusement park.

Although Mayor Stokes cared more about expanding the city’s supply of affordable housing and improving access to industrial jobs, he was also conscious of the need to attend to Cleveland’s image, and nowhere was better for that than downtown, which inspired metaphorical description as the city’s “showcase,” “heart,” or “mainspring”—in short, a place thought to possess central economic and symbolic importance for the metropolitan area. Following a period when two previous mayors had struggled to produce just three sizable new downtown buildings even with the promise of the nation’s largest federally subsidized downtown urban renewal project, Stokes made regular use of his spade and scissors at groundbreaking and dedication ceremonies for an impressive roster of new high-rises. More importantly, his administration was attuned to the need to do more than simply rely on a building boom to create a larger captive audience of office workers that might stave off the decline of downtown retailing.

As in other American city centers, downtown Cleveland experienced a loss of shoppers to suburban shopping plazas after mid century. At a time when San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square, a former chocolate factory converted into a shopping, dining, and entertainment complex, was an influential model for reorienting central cities as destinations for suburbanites and tourists, Cleveland planners were taking note. While the city’s 1965 reevaluation of the 1959 downtown plan continued to recommend the “malling” of Euclid Avenue as an antidote to retail decline, it also noted the 1890 Arcade’s potential to be Cleveland’s answer to Ghirardelli Square. Although the Arcade did not materialize as a major tourist venue, Stokes was the first mayor to actively pursue a leisure-driven agenda for downtown Cleveland as part of a broader effort to rejuvenate a city beset by problems. In the downtown segment of his televised Cleveland: NOW! documentary in 1968, the mayor told of a French magazine writer who remarked during a visit to Cleveland on how deserted the downtown streets became after dark. Stokes believed downtown could become a “people place.”

The mayor’s vision found an advocate in Ed Baugh, who had recently left the Peace Corps to serve as Stokes’s city properties director. From his City Hall office, Baugh looked out on the Mall, one of the nation’s few Daniel Burnham City Beautiful plans to be implemented to a significant degree, and he saw an attractive but little-used expanse. In his mind’s eye, Baugh conjured a Tivoli on the Mall—piped music, live concerts, cafes, surrey rides, and nighttime floodlighting—as an antidote for what one of the city’s daily newspapers called Cleveland’s “grim, all-business image.” With the mayor’s blessing, Baugh opened the Mall Café and staged events such as Mall-A-Rama, with games, crafts, and even model boat races in the fountain pool, and Fun Day on the Mall, a music festival that brought rock and R&B acts headlined by Edwin Starr. Significantly, the administration took pride in drawing together a diverse audience and saw diversity as essential to the city’s future.

Baugh extended his version of the “Fun City” mindset that Mayor Lindsay championed in New York beyond the Mall. The administration recognized the potential of efforts by business owners and the Old Flats Association to turn the rough-and-tumble docklands of the Flats along the Cuyahoga into a place fit to be mentioned in the same breath as Old Town Chicago or Gaslight Square. The Old Flats Association, formed in 1968 by business owners such as Harry Fagan, (whose four-year-old tavern featured a New Orleans-style jazz band), found an ally in Baugh and the Stokes administration, which added gas lamps and signage and worked with organization to sponsor a rededication of the site where city founder Moses Cleaveland landed in 1796.

Even as the Stokes administration worked to carve out new entertainment destinations, it also labored to restore one that had been lost. The Playhouse Square area on downtown’s eastern end had once hummed with activity. In addition to the 12,000 seats in five theaters, dozens of fashionable stores and large restaurants lent a Times Square-like quality that persisted long after sunset. When the theaters closed, their demise took down a number of nearby businesses. Concerned business owners formed the 9-18 Corporation (named for East 9th and 18th Streets, which marked the boundaries of the part of Euclid Avenue the organization served). The 9-18 Corporation partnered with the mayor’s office to relight Euclid Avenue with super-bright “Lucalox” bulbs developed at General Electric’s Nela Park, its lighting division campus in East Cleveland.

Stokes’s predecessor, Ralph Locher, had undertaken a citywide plan for replacing streetlights with a similar symbolic gesture as part of a demonstration project to jumpstart a moribund urban renewal project in Hough just months prior to the Hough uprising, but before the relighting campaign could progress far, the murder of a Cleveland Orchestra chorister in the heart of University Circle forced the mayor to redirect new lighting to allay fears in the city’s cultural district. Three years later Stokes was making a similar move to quell concerns about the dark, forbidding stretch where theater marquees had until recently blazed with light. As Stokes’s utilities director later recalled, the Lucalox treatment was “something visual” to help “taxpayers see where their dollars were going,” and it was predictably touted as another public service of Cleveland: NOW! On a late October evening in 1969, the mayor flipped a ceremonial switch to dedicate what he claimed was now the brightest downtown in the United States and spoke of his hope for reinvestment in Playhouse Square.

The mayor went a step further. Understanding that the 9-18 Corporation, like so many other organizations formed over the years in the interest of promoting specific sections of downtown, was insufficient to the task of promoting all of the central business district, Stokes worked with business leaders to form the Downtown Consortium in 1970. The Downtown Consortium was Cleveland’s first public-private partnership to coordinate revitalization in the district. The new organization pledged to continue supporting efforts to revive Playhouse Square while also undertaking a variety of symbolic interventions. Perhaps the most noteworthy was the plan to hold a downtown festival and, at Ed Baugh’s suggestion, use the event to test an idea first hatched in the 1959 downtown plan: making Euclid Avenue into a pedestrian mall. The closure of the street for the festival separated this event from previous festivals sponsored by business interests, but it did not lead to a permanent “malling” of the street, leaving future planners to continue debating the concept through the 1970s.

Clevelanders may not have seen the immediate coalescence of a leisure-driven downtown transformation, but they certainly learned to see their city as having the potential to move in that direction. Indeed, it was at this time that Herbert Strawbridge, the chairman of the Higbee Company, a leading local department store, having recently visited Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco, began seriously thinking about making a bold move to use his store as a developer of a similar complex in the Flats. He thought of it as a way of making Higbee’s future less dependent on office workers by creating a powerful magnet for suburbanites and tourists. Strawbridge would take the plunge in 1972 when, after he read in the newspaper that a junkyard was planned on the site of Moses Cleaveland’s river landing nearly two centuries before, he resolved that Higbee’s could not stand by and watch the desecration of “Cleveland’s Plymouth Rock.”

The Stokes era, now being celebrated in the golden anniversary year of his historic election, was a might-have-been watershed in Clevelanders’ efforts to jar their city onto a new course of revitalization. We now know very well that, not only in Stokes’s time but also throughout the half century since, decline and revitalization are not sequential but coexist in perpetual tension. Many times we have seen mayors, business leaders, and other urban prognosticators declare that revitalization is at hand—that a city has “turned the corner” or embarked on a “comeback.” History tells us that it’s rarely so simple. Revitalization is something that must be forever cultivated. That is exactly what Carl Stokes understood. He knew and often admitted that Cleveland’s problems were real and should not be swept under the rug. Yet, as he worked to steel the public for a long, expensive, and sometimes controversial struggle for a better city, the mayor also understood and deployed the symbolic rhetoric and actions that he knew might help manage people’s response to the challenges ahead.

Mark Souther is a Professor of History at Cleveland State University. Souther will be speaking on October 27 in the “Alternative Visions for Cleveland” roundtable at this year’s SACRPH conference. This essay was adapted from Souther’s new book Believing in Cleveland: Managing Decline in “The Best Location in the Nation” (Temple University Press, 2017). Souther is also the author of New Orleans on Parade: Tourism and the Transformation of the Crescent City (LSU Press, 2006).

2 thoughts on ““PEOPLE WERE SAYING NICE THINGS ABOUT CLEVELAND AGAIN”: REFLECTING ON CARL STOKES AND CITY IMAGE”