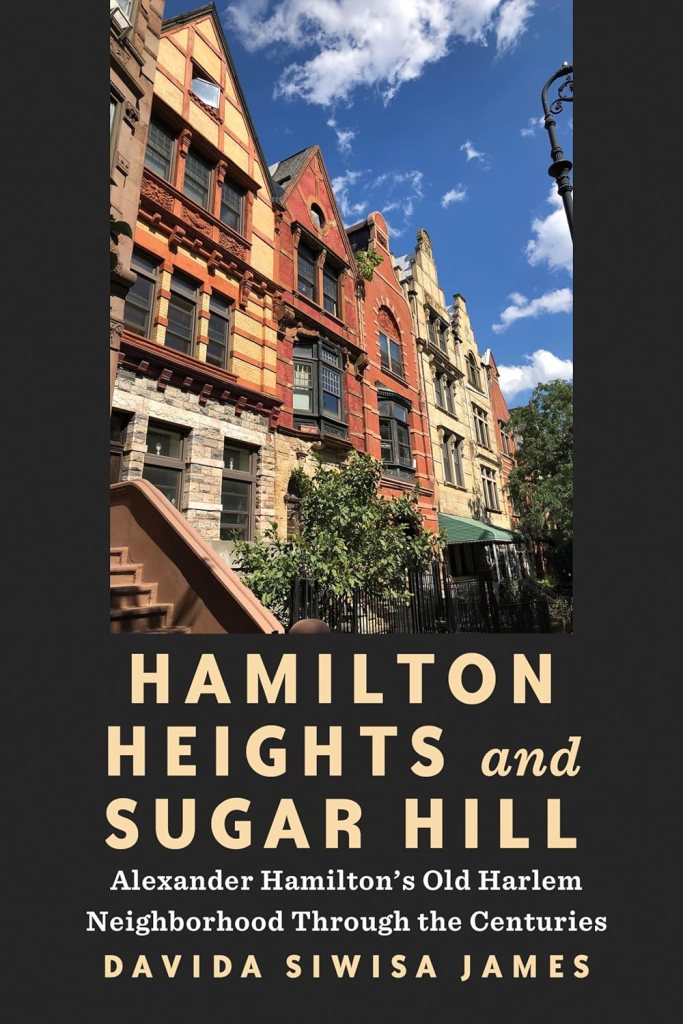

Davida Siwisa James. Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill: Alexander Hamilton’s Old Harlem Neighborhood Through the Centuries. New York: Fordham University Press, 2024.

Reviewed by Kevin McGruder

In Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill: Alexander Hamilton’s Old Harlem Neighborhood Through the Centuries, author Davida Siwisa James uses several individual buildings and collections of buildings, the people who built them, and the people who occupied them to describe the centuries-long, rich history of the Upper Manhattan neighborhoods that came to be known as Harlem, Hamilton Heights, and Sugar Hill. Among them are the Morris-Jumel Mansion, The Hamilton Grange, Convent Avenue townhouses, the James A. Bailey Mansion, and 555 and 409 Edgecombe Avenue. The book is an ambitious, comprehensive social and architectural history that provides a chronology that leaves the reader with an appreciation for the people and places that made these Upper Manhattan communities important to New York City and U.S. history.

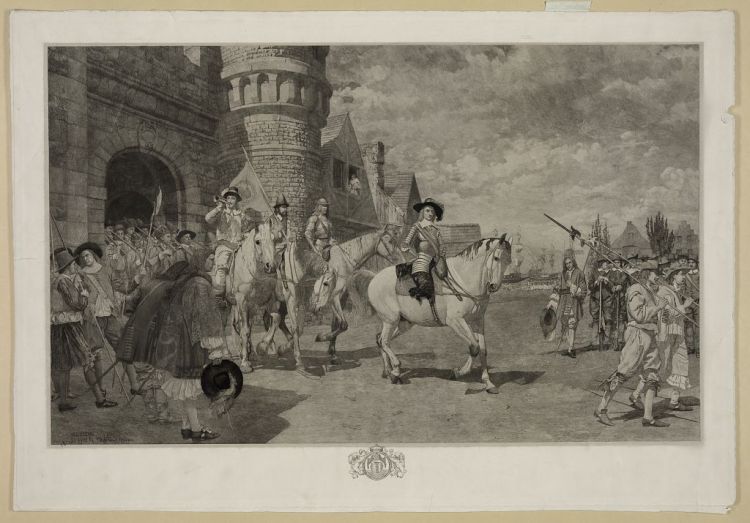

James’ straightforward narrative begins with the initial encounters and conflicts between the Lenape, Indigenous people who for centuries occupied what would become Manhattan (they called it Manna-hatta), and the Dutch, who arrived in the 1620s and established the city of New Amsterdam as the capital city of their colony of New Netherland. She introduces early families such as the DeForests, the van Rensselaers, and Jonas Bronck, all of whom claimed and settled on properties in Upper Manhattan, where the Lenape first traded with them and then occasionally attacked them as the Dutch population grew. Outnumbered, the Lenape eventually moved to another territory, and in the 1650s, the Dutch established the Upper Manhattan village of Nieuw Haarlem, named after the Dutch city of Haarlem. New Amsterdam and Nieuw Haarlem continued to prosper after the English seized New Netherland in 1664 in a bloodless confrontation. They renamed the colony and the city, then concentrated in Lower Manhattan, New York after the Duke of York. It was several hours south of the village of Haarlem by horse. The author details the challenges Dutch and English officials faced in managing the growth of the Harlem in its early decades.

James uses Mount Morris, the estate completed by British Colonel Roger Morris and his wife Mary Philipse in 1765, on land that ran from what is now 159th to 174th Streets, to provide a window onto the late colonial period in Upper Manhattan. Built on one of the island’s highest points, the estate was a working farm but also a country home that was elegant, with a widow’s walk from which “one could savor uninterrupted 360-degree views: across the Harlem River to Bronck’s land, the Hudson to the north with New Jersey in the distance, the vast virgin Harlem lands stretching to Spuyten Duyvil, the Harlem Flats, and New York City” (Lower Manhattan).[1] Other wealthy British, such as the Maunsells and the Bradhursts, established country estates in the area as well. During the War for Independence, when the Morrises, who remained loyal to King George, abandoned the property, Patriots seized it. In the summer of 1776, before the battle of Harlem Heights, George Washington used the Mount Morris home as his headquarters.

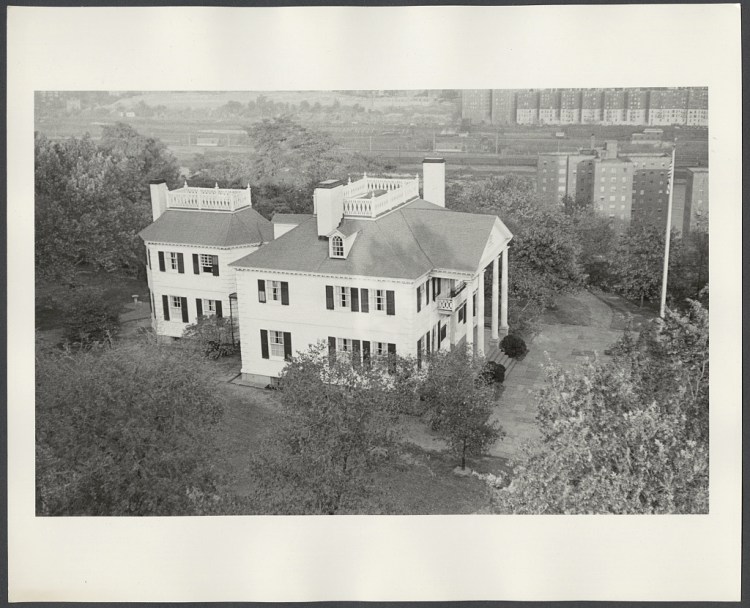

James employs the Hamilton Grange, the estate that Alexander Hamilton established after serving as Secretary of the Treasury in the Washington administration, to describe Upper Manhattan activities during the Early National period. Located on fifteen acres of land, purchased by Hamilton in 1799, between what is now 141st and 147th Streets, near the Hudson River to what is now St. Nicholas Avenue, “the majestic views of woods, flowers, and rivers, with streams running through the property, convinced him to choose this site”.[2] Designed by architect John McComb Jr. (who also would design New York City Hall) in the Federalist style, James suggests that Hamilton “likely contributed to the plans” for the estate home and “was heavily involved with the creation and design of the gardens”.[3] When Hamilton, his wife Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, and their seven children moved into the home in 1802, Hamilton was often seen “wandering through the nearby woods, where he hunted woodcock and other game and fished in the clear waters of the Hudson”.[4] He would have only two years to enjoy the home before his death at forty-seven in 1804 following a duel with Aaron Burr. The future of the Grange after Hamilton’s death, in many ways, serves as a central motif for Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, as well as a metaphor for the rise, fall, and rise again of the two Harlem neighborhoods and the two centuries that followed the death of Alexander Hamilton.

James moves the narrative of the neighborhoods into the nineteenth century as it transitioned from a small village that was annexed as part of New York City in 1879 into a genteel city neighborhood. The construction of the James A. Bailey Mansion and the townhouses in the Convent Avenue area (featured on the cover of the book), the people who designed them, and those who lived there provide the reader with a sense of the thriving late nineteenth-century community. The Hamilton estate had passed through several hands after the 1854 death of Hamilton’s widow. In 1879, William H. DeForest, a descendant of one of the early Dutch settlers of Harlem, purchased the house and land and, in the 1880s, began building three-story townhouses on 144th Street, setting a pattern that was followed along the streets surrounding Convent Avenue that would become known as Hamilton Heights.

James explains the preservation of the Grange home by noting that in 1887, St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, then located on Hudson Street in Greenwich Village, needed to relocate when Trinity Church Wall Street decided to build on land it owned surrounding St. Luke’s. The congregation purchased land on Convent Avenue at 141st Street for a new church. Needing a location for worship services during the construction, they purchased the Hamilton Grange home from its owner, Amos Cotting. The home was moved to a location adjacent to the site of the new church, and services were held there from 1889 until 1892 when the Richardsonian Romanesque church building was completed. The church continued to use the Grange home for its rector and later for other purposes.

In 1890, the construction of an 8,250 square-foot mansion at 10 St. Nicholas Place at 150th Street was completed by Barnum & Bailey circus magnate James A. Bailey. With thirty-two rooms “adorned with arches, gables, and tiled porches topped with spires” different woods in various rooms, and sixty-four stained-glass windows, the house was a showplace.[5] Unfortunately, by the time the home was completed, the surrounding area had shifted from a bucolic retreat to a semi-suburban neighborhood, leading Bailey to sell the home within a decade. After a series of owners, in 1951, the home was purchased by Marguerite and Warren Blake, who restored the home and established M. Marshall Blake Funeral Home.

Moving the narrative into the twentieth century, Davida Sawisa James similarly focuses on key buildings and those who lived and visited them. She provides a concise description of the movement of large numbers of African Americans to Harlem in the 1910s and 1920s and explains how Harlem Renaissance figures who lived in Upper Manhattan, such as librarian Regina Anderson Andrews and band leader Duke Ellington, earned the thriving Sugar Hill neighborhood its name as a location where sweet, good things happened. The greater visibility of Black writers, musicians, and other artists in the 1920s that became known as the Harlem Renaissance was identified with writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston and artists such as Aaron Douglas. Some of them lived in Central Harlem rather than Sugar Hill and Hamilton Heights, but many socialized in the two Upper Manhattan neighborhoods.

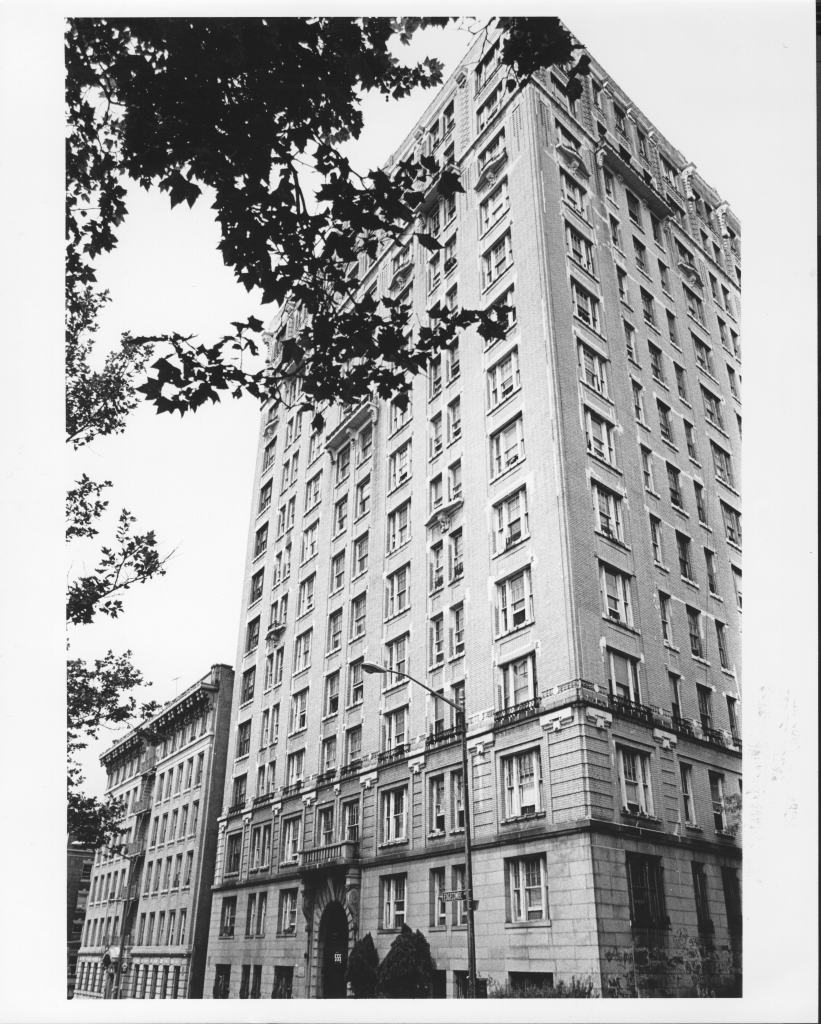

Two large apartment buildings completed in the 1910s for White residents and located on Coogan’s Bluff, a cliff that overlooked the valley of Central Harlem to the east, in later decades would come to define the Sugar Hill neighborhood for Black residents of Harlem. Completed in 1917, 409 Edgecombe Avenue, a thirteen-story plus penthouse luxury apartment building, by the late 1920s, had become a favored residence for many of Black Harlem’s high-profile residents such as scholar W.E.B. DuBois, singer Paul Robeson, NAACP official Walter White, and many others. Just north of 409, the Roger Morris Apartments, at 555 Edgecombe Avenue, near the Morris-Jumel Mansion, opened in 1916 and had an equally prominent collection of Black residents. These two high-rise buildings became symbols of Black achievement in the same way that the historic townhouses on West 138th and 139th Streets, known as Strivers’ Row, did beginning in the 1920s.

Music is an important through-line that James uses to describe Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill in the twentieth century. She highlights the jazz clubs, such as St. Nick’s Pub, that thrived in the mid-twentieth century on St. Nicholas Avenue, as well as their decline in the early 2000s. She explains the importance of the Harlem School of the Arts on St. Nicholas Avenue, which began in a church basement and now occupies a half-block-long space funded in part by trumpeter Herb Alpert. She notes that pianist Mary Lou Williams’ Hamilton Terrace townhouse became a “salon-style gathering place for jazz musicians in the 1950s and ‘60s.”[6] James gives particular focus to the parlor jazz, Sunday jam sessions hosted by Marjorie Eliot in her apartment at 555 Edgecombe, which began in the 1990s and continue today with occasional larger performances held on the grounds of the Morris-Jumel Mansion.

Moving into the latter decades of the twentieth century, James describes the challenges faced by the Hamilton Grange and the Bailey Mansion and the eventual restoration of both buildings as symbols of the enduring vibrancy of Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill. Alexander Hamilton’s estate house went through a period of neglect in the mid-twentieth century before being designated a historic landmark and coming under the auspices of the National Park Service. Still squeezed between St. Luke’s Presbyterian church and an apartment building, the decades-long dream of moving the home to a more appropriate location came to fruition in 2008 when it was moved to nearby St. Nicholas Park and reopened after a $14 million investment that restored the interior spaces, returned the porches that had originally been on both sides of the building, and created a visitor’s center on the ground level. James notes that the timing of the completion of the restoration enabled it to benefit from the renewed attention in Alexander Hamilton’s life that followed the tremendous success of the Broadway musical Hamilton. Tens of thousands of people now visit the Grange annually. In 2000, the Bailey Mansion, purchased in 1951 by Marguerite and Warren Blake, and the base for M. Marshal Blake Funeral Home, was severely damaged by a fire. The Blakes relocated to an apartment nearby, and the business was closed. In 2009, the Bailey Mansion was purchased by a couple who began a painstaking restoration of the home that was still underway in 2021 when James visited it.

Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill is an important addition to books about New York City and Harlem. James could have broadened the musical theme that she uses beyond jazz to other musical forms identified with residents of the area, such as doo-wop figure Frankie Lymon (“Why Do Fools Fall in Love?”), and hip hop by broadening her descriptions of graffiti artist and documentary filmmaker Fab 5 Freddy, whom she notes in the 1990s purchased the Hamilton Heights townhouse of National Urban League co-founder George Edmund Haynes. As someone who lived in Hamilton Heights for over twenty-five years, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill introduced me to many aspects of its early history that I did not know, as well as provided me with a much better understanding of the people and places that made the neighborhoods of Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill the vibrant communities that they remain today.

Kevin McGruder, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of History at Antioch College and the author of Race and Real Estate: Conflict and Cooperation in Harlem, 1890-1920, and Philip Payton: The Father of Black Harlem.

Featured image (at top): The Surrender of Nieuw Amsterdam in 1664. Print by Charles X. Harris, 1856-, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Davida Sawisa James. Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill: Alexander Hamilton’s Old Harlem Neighborhood Through the Centuries. New York: Fordham University Press, 2024, 26-27.

[2] James, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, 43-44.

[3] James, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, 45-46.

[4] James, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, 47.

[5] James, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, 83.

[6] James, Hamilton Heights and Sugar Hill, 312