Jesse Chanin. Building Power, Breaking Power: The United Teachers of New Orleans, 1965-2008. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2024.

Reviewed by Daniel G. Cumming

Ten years after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, a Chicago Tribune columnist memorialized the catastrophe with disturbing notes of envy. Though full of chaos, tragedy, and heartbreak, she said, “that’s what it took to hit the reset button.” As she put it, “Hurricane Katrina gave a great American city a rebirth.” In a shockingly callous piece, the columnist even found herself “wishing for a storm in Chicago.” One can assume, of course, not in her neighborhood; such macabre wishes, even “prayers,” for a massive leveling event were purely metaphorical, the columnist insisted in a later apology. Even so, her column revealed a certain truth about how many people condemned New Orleans at the time; this was a city that had to drown before it could be reborn.[1]

Much has been written about Katrina and New Orleans. The city offers a generative site for studies of disaster capitalism, environmental injustice, social movement history, and “Blues geographies,” among others.[2] Its school system, in particular, is important in histories of public education, not least of all because post-Katrina New Orleans became a front line in the national education reform movement. Indeed, in the wake of the storm New Orleans replaced all its schools with privately-run charter networks, becoming the only city in the country with a 100 percent chartered district. According to our columnist, this was an exciting development, producing “the nation’s first free-market education system.” But for others, the district’s dismantling was traumatic and caused lasting resentment, especially among teachers, most of whom were unionized with the United Teachers of New Orleans (UTNO). In the largest dismissal of Black teachers since Brown v. Board Education, roughly 7,500 educators lost their jobs. New Orleans teachers could only watch as decades of classroom expertise washed away with the receding flood water.

Jesse Chanin, postdoctoral fellow and research facilitator at Tulane University, would like a word. Delving into local and state archives, conducting over fifty interviews, and interrogating the forces that “eviscerated” New Orleans public schools, Chanin provides an excellent history of the people who made the system work, anchored its communities, and never failed to advocate for its students. Building Power, Breaking Power: The United Teachers of New Orleans, 1965-2008 (UNC Press, 2024) makes important contributions to the fields of labor history, education history, Southern history, African American history, and urban histories of neoliberalism.[3]

Telling the full story of the largest teachers’ union in Louisiana and one of the strongest in the South, Chanin provides an important bridge between civil rights unionism and social movement unionism in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Her attention to UTNO’s “bargaining for the common good,” in which unions organized with communities to fight simultaneously for racial and economic justice, corrects any misguided attempts to undervalue teachers’ unions in the South, Black women’s activism in the labor movement, and Black-led institution building in the post-civil rights era. Chanin offers a nuanced analysis of how elite powerbrokers infused with anti-labor, anti-democratic, and anti-Black animus gained momentum through an education reform movement in the 1990s and targeted public institutions in the lead-up to the storm.

A core theme of Building Power is the entrenched conflict between labor and capital, and under state deregulation, capital’s “creative destruction,” or in this case, privatization, of a public school system.[4] Private management, high-stakes testing, colorblind policies, consumer-choice vouchers, merit-based pay, and crucially no unions—key elements of the “neoliberal education reform agenda,” as Chanin frames it—undermined UTNO’s ability to fight for an equitable redistribution of public resources. Still, UTNO held off privatization for decades, even notching significant wins through collective bargaining agreements, community-backed strikes, and worker-led institutions. Katrina, however, destroyed this tenuously negotiated stalemate.

Chanin resists wading too deeply into the aftermath. Instead, Building Power is just that, a history of Black-led, interracial institution building in the decades prior to the storm, one that seems to have been publicly forgotten, politically maligned, or, like so much else after the deluge, simply erased. The book begins in 1965 when the American Federation of Teachers Local 527 launched its first campaign for collective bargaining. Founded originally in 1937 by Black educators (a rich history in its own right), Local 527 launched the first teacher’s strike in the South in 1966, a three-day action backed by the national AFT. In 1969, the local struck again, holding a nine-day picket line that galvanized teachers, students, parents, and the community. After the district entered a faculty desegregation plan in the early 1970s, Local 527 merged with a majority-white local to form UTNO, then pressured the school board with interracial mobilization and finally won its collective bargaining agreement in 1974.

UTNO’s collective decision making and robust member-led activism fueled its early victories. The union prioritized participatory democracy, political education through militant action, and community-wide demands for racial and economic justice. Chapter two will satisfy labor historians looking for a thorough analysis of union leadership, rank-and-file organization, community engagement, labor-political alliances, and strike mobilization in a pivotal decade often considered a period of labor decline. Chanin offers a strong counterpoint to the latter, showing how UTNO instead created lasting institutions, including a health and welfare fund, a center for professional development, a credit union, and a political machine involved significantly in local and state politics. The chapter concludes with UTNO’s 1978 strike, another successful action that welcomed clerical workers into the union fold.

Chapters three and four mark the beginning of local, state, and federal backlash to growing labor power. Following national trends, Louisiana became a ‘right-to-work’ state in 1976, a clear maneuver to contain the state’s largest teacher’s union. By the 1980s, economic recession in the oil industry, followed by politicians’ austerity measures, eviscerated public funding for schools. As a result, UTNO’s fight for education investment was constricted to a tight budgetary arena. Metropolitan decentralization, moreover, which led to resource hoarding in the suburban periphery and concentrated poverty in the urban core, eroded the city’s ability to fund basic infrastructure. As barometers of societal well-being, the city’s public schools began to register clear signs of warning.

Powerful business interests began to align under the new banner of a “neoliberal education agenda.” Fueled by the scandalous report A Nation at Risk (1983), the reactionary administration of Ronald Reagan, and corporate-led reforms like school vouchers and charter networks, officials engineered new ways for profiteering through the private delivery of public goods. By the 1990s, UTNO was weathering repeated assaults by corporate-backed politicians and reformers, including charges of corruption, incompetence, and mismanagement. Though union members were less united than in previous decades, UTNO went on strike again in 1990, proving its enduring commitment to the city’s Black working class and fighting for low-paid and unprotected paraprofessionals. Successful, though not without widening fault lines, UTNO countered privatization’s initial assault by demonstrating that public education required expansive investment in the city’s workers and institutions.

Though the 1990 strike inspired many and, in certain ways, harkened back to the union’s golden years, critics were legion and only growing stronger. Louisiana legalized charter schools in 1995, followed by New Orleans’s first charter experiment in 1998. Privately run and publicly exempt charter networks began to appeal to a much wider audience, including parents frustrated by underfunded public schools. The structural consequences of a near-frozen state budget and the difficulty in passing school bonds, much less increasing property taxes, meant public facilities suffered serious neglect. Critics turned on “bad” teachers and blamed UTNO for protecting them. Charter schools, moreover, appeared to offer choice and mobility within ostensibly colorblind markets, part of a façade that Jodi Melamed calls “neoliberal multiculturalism.”[5] UTNO even conceded some of the terrain, not realizing fully what was on the horizon.

On both sides, Chanin is fair and balanced in her analysis. Unwilling to give any oxygen to rhetoric that blamed the union for systemic failure with racist and sexist caricatures, she is critical of the problems that undermined public education in the city—problems that UTNO aimed to redress by demanding more public investment. In the years leading up to Katrina, Chanin examines a near-revolving door of superintendents, standardized testing under state legislation (then No Child Left Behind), investigations into school board corruption, the formation of a state-run Recovery School District, and a change in union leadership that proved a difficult transition. Taken together, these pressures blunted UTNO’s militancy and risked institutionalizing the union into a bureaucratic “oligarchy,” a common trajectory among social movements, as Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward have argued.[6]

The final chapter opens with Katrina flooding the city. Chanin uses Naomi Klein’s “disaster capitalism” to examine the state’s takeover and policymakers’ decision to fire 7,500 school employees, 4,000 of whom were teachers.[7] UTNO did its best to fight back. Still, eight years after the storm, only 22 percent of its original teachers remained. Black teachers fell from 79 to 49 percent of the teaching force, and new teachers with 0-5 years of experience grew from 33 to 54 percent.[8] Under the auspices of state authority and backed by a school board that declined to renew UTNO’s contract, charter networks like KIPP, and alternative certification programs like Teach for America—a phalanx in the educational reform movement—remade the city’s entire school system root and branch. By 2019, New Orleans schools were an entirely charter-run district, ground zero for the “no excuses” school reform movement. Importantly, Chanin argues that UTNO was attacked because the union had institutionalized a strand of Black political power long opposed to corporate capital and market-driven reforms. “Policymakers’ targeting of UTNO,” she concludes, “was an intentionally anti-Black, anti-labor neoliberal project,” one that attempted to recast the union as corrupt, failing, and unwilling to change.[9]

Tragically, what had made UTNO strong, namely its people power, also made it vulnerable. Scattered across the country, navigating personal and generational loss, reeling from severance announcements, and unable to return to schools that officials kept closed, UTNO’s members were forcibly displaced from the union’s base of participatory democracy. UTNO became “a shell of its former self,” Chanin writes, and “did not have sufficient bureaucratic structures in place to mount resistance to the reform agenda without its members present.”[10] Policymakers accomplished in months what they previously could not in decades. Ultimately, UTNO was cracked open by a once-in-a-century storm, then gutted by corporate reformers who had been sharpening their knives for decades.

Though far from perfect, UTNO presents an inspiring model of successful unionizing in the Deep South. Built over forty years by dedicated members, the majority of whom were African American and three-quarters of whom were women, UTNO’s role in the state’s labor movement and in the education of generations of New Orleanians is undeniable. UTNO’s place in the city, however, remains a little unclear. Overall, the book’s strength as a labor history is less apparent as an urban history. The tight narrative focus on the union glosses over where its members lived, worked, played, and prayed. Chanin discusses postwar urban dynamics, most prominently suburban white flight, but complicated processes of metropolitan history are often listed together rather than explored in detail. One is left wondering, for example, how urban renewal, public housing, and highway construction, among later touchstones such as downtown redevelopment, shaped and reshaped teachers’ living and working environments over time.

A closer reading of the urban landscape might have allowed Chanin to elaborate more fully on UTNO’s changing relationship with neighborhood-based communities. While UTNO was a pillar of Black middle-class stability, union gains began to distance members from the working-class families they served. As she puts it, “the Black community’s support for UTNO waned over the 1990s and 2000s as class divisions within New Orleans Black population grew.”[11] Chanin analyzes this tension by examining UTNO’s efforts to bridge middle and working-class interests, especially on the picket lines and with inspired collective bargaining agreements. Early on, UTNO operated as a “middle-class mediator.” However, with class strains noted in the very first strike, Chanin argues that union wages and benefits began to divide teachers economically from the students they taught.[12]

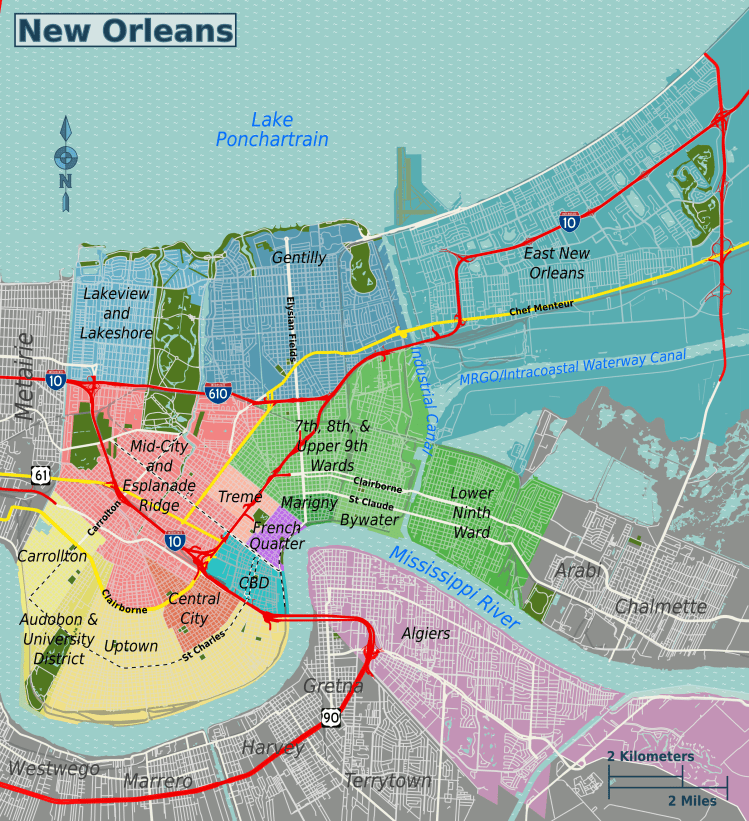

In all likelihood, teachers were also buying into housing markets once defined by racial segregation yet still shaped by class exclusion. At the very least, “a large number” began enrolling their children in private schools.[13] Though initially, UTNO’s members lived in “mixed income” neighborhoods[14] and “likely rejected their white peers’ flight to the suburbs,”[15] by the 1980s, Black middle-class homeowners were redeveloping the city’s periphery, from Gentilly and Pontchartrain Park to New Orleans East, even beyond Orleans Parish. This might leave readers wondering where exactly upwardly mobile teachers lived and how local real estate capital may have intensified the class divisions Chanin identifies. Later, many of these same neighborhoods, especially in New Orleans East, would suffer among the worst damage caused by Katrina.[16] Homeowner politics, moreover, helped underwrite austerity budgets and, eventually, school privatization. UTNO had to fight tooth and nail for every public dollar because, in addition to regressive state taxes that favored industrial and corporate exemptions, voters refused to increase property taxes for thirty-three years (not until 1988).[17] New Orleans’s Homestead Exemption, for example, still shields homeowners from the first $75,000 of property taxes. By the 1990s, “the city was broke.”[18]

At the same time, UTNO’s political machine supported Black politicians who advanced teachers’ interests through the city’s interracial growth coalition. One can imagine, though, the contradictory positions teachers must have navigated when this downtown political regime deepened urban inequality by demolishing public housing, promoting corporate-led gentrification, and building one of the most punitive carceral systems in the country.[19] Some members, Chanin acknowledges, even welcomed officials’ growing appetite for criminalization, “potentially pathologizing their poorer neighbors.”[20] While Building Power explores the complicated position of Black middle-class politics in a city wracked by retrenchment and speculation, Chanin does so largely through UTNO’s institutional lens rather than teachers’ social-political geography in the deindustrializing metropolis. An urban history of the union, rather than a union history within the city, might have helped answer some of these questions for readers of The Metropole.

These are less critiques of an important book than possibilities for future research. As a former teacher in New Orleans and New York City, Chanin’s commendable efforts against the historical erasure of one of the most important teachers’ unions in the South highlight the rewards of deeply committed community-based scholarship. Not only did her fifty-plus oral histories reveal key insights about UTNO, but her forty-six FOIA requests into charter networks and her digitization of the union’s unprocessed archive are valuable contributions that will no doubt benefit future scholars. Though heavy at times considering the legacy of Hurricane Katrina, Building Power, Breaking Power offers a rich and insightful history for scholars, interested readers, and, of course, educators looking for teaching materials or even inspiration in organizing across civil rights and social movement eras.

Daniel G. Cumming, Ph.D., is an urban historian of the twentieth-century U.S. and currently a postdoctoral fellow at Queens College, City University of New York. He previously held a postdoc with the Chloe Center for the Critical Study of Racism, Immigration, and Colonialism at Johns Hopkins University. He is writing a book on postwar Baltimore, and his scholarship explores the intersections of environmental inequality, racial capitalism, and metropolitan history.

Featured image (at top): Colorful row houses in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, between 1980 and 2006, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Chanin cites this column as an example of popular discourse that demonized New Orleans and dehumanized its residents, especially its teachers. Kristen McQueary, “Chicago, New Orleans, and Rebirth,” Chicago Tribune, August 13, 2015.

[2] Among many, see Robert D. Bullard and Beverly Wright, eds., Race, Place, and Environmental Justice After Hurricane Katrina: Struggles to Reclaim, Rebuild, and Revitalize New Orleans and the Gulf Coast (Philadelphia, Westview Press, 2009); Andy Horowitz, Katrina: A History, 1915-2015 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020); Cedric Johnson, ed., The Neoliberal Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, Late Capitalism, and the Remaking of New Orleans (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011); Clyde A. Woods, with Jordan T. Camp and Laura Pulido, eds., Development Drowned and Reborn: The Blues and Bourbon Restorations in Post-Katrina New Orleans (Athens, The University of Georgia Press, 2017).

[3] Chanin positions her study in conversation with Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (2005): 1233-63; Ansley T. Erickson, Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Pauline Lipman, The New Political Economy of Urban Education: Neoliberalism, Race, and the Right to the City (New York: Routledge, 2011); Nancy MacLean, Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008). Mary Pattillo, Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Elizabeth Todd-Breland, A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago Since the 1960s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018); and Lane Windham, Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), among others.

[4] David Harvey, “The Right to the City” (2008) and A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), cited by Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 110, 167, 182, 216.

[5] Jodi Melamed, Represent and Destroy: Rationalizing Violence in the New Racial Capitalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), cited by Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 14, 151, 179.

[6] Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Vintage Books, 2012), cited by Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 16, 152, 201.

[7] Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2007), cited by Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 13, 182, 211.

[8] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 216.

[9] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 181.

[10] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 191.

[11] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 10.

[12] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 59-60.

[13] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 18.

[14] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 17.

[15] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 100.

[16] Horowitz, Katrina, 7-8, 93-94; John R. Logan, “The Impact of Katrina: Race and Class in Storm-Damaged Neighborhoods” (unpublished manuscript, Spatial Structures in the Social Sciences Initiative, Brown University, 2006): 299-306.

[17] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 124.

[18] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 115.

[19] See for example, Megan French-Marcelin, “Doing Business New Orleans Style: Racial Progressivism and the Politics of Uneven Development,” in Andrew Diamond and Thomas Sugrue, eds., Neoliberal Cities: The Remaking of Postwar Urban America (New York: NYU Press, 2020); Cedric Johnson, “Gentrifying New Orleans: Thoughts on Race and the Movement of Capital,” Souls 17, no. 3-4 (2015): 175-200.

[20] Chanin, Building Power, Breaking Power, 12.