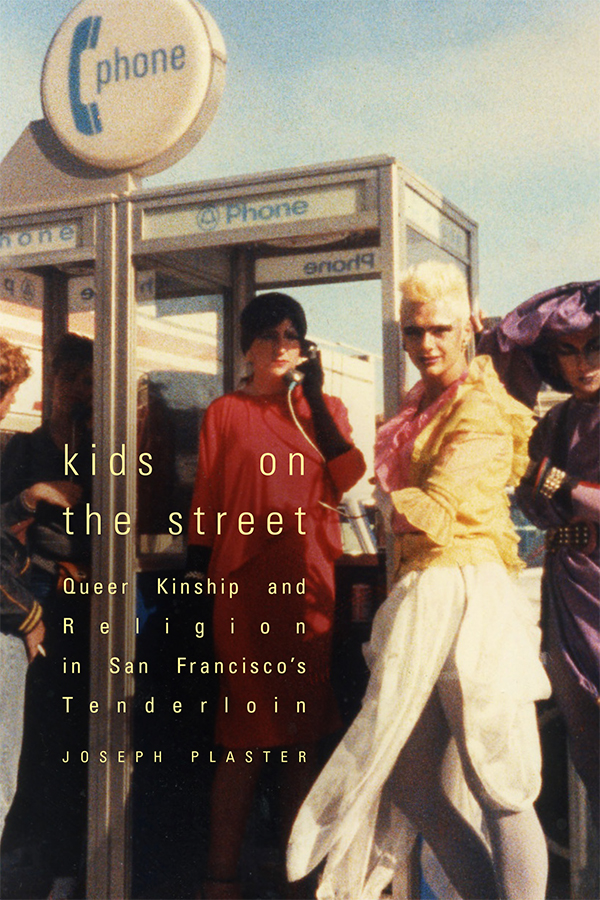

Plaster, Joseph. Kids on the Street: Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco’s Tenderloin. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023.

Reviewed by Alex Melody Burnett

At the height of the coronavirus pandemic, national media outlets developed a powerful new narrative about San Francisco. After years of tech-induced prosperity, San Francisco had supposedly entered a dangerous period of urban decline characterized by alarming rates of homelessness and drug addiction—a “doom loop,” as the San Francisco Chronicle declared in March 2023. According to the doom-loop narrative, San Francisco was rapidly becoming a “crime-ridden” wasteland, which could no longer attract white-collar professionals and their valuable tax dollars. “This is how San Francisco could die,” the San Francisco Chronicle warned, citing “the possibility of a return to 1960s-1970s mass migration from cities to suburbs.” In a November 2023 interview with Fox & Friends, Jeremy Bernier, a tech startup builder, offered a similarly bleak assessment of San Francisco’s post-pandemic prospects. “This is a disgrace,” Bernier said, regarding San Francisco’s unhoused population. “I’ve been to 50-plus countries and traveled the world. I’ve never seen anything like this.” In the doom-loop imaginary, San Francisco seemed like an exceptionally sinister and dystopian place, teetering on the brink of death.

Much of the doom-loop narrative centered on the Tenderloin—a low-income neighborhood that has long functioned as “a containment zone” for drug users, sex workers, Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees, and unhoused people. Once described as San Francisco’s “white ghetto,” the Tenderloin is currently mostly populated by people of color: 71 percent of residents are Asian, 14 percent are Latinx, and 10 percent are Black. Formerly filled with gay bars and single-room-occupancy hotels (SROs) that catered to gender-nonconforming youth, the Tenderloin has played a prominent role in San Francisco’s queer and trans histories.[1] As Susan Stryker and Victor Silverman have documented in their Emmy-award-winning documentary, the Tenderloin served as the backdrop for the August 1966 riot at Compton’s Cafeteria—one of the earliest collective uprisings against sexual policing in United States LGBTQ history. Many of Compton’s customers were homeless trans and gay teenagers, who flocked to the Tenderloin in search of companionship and freedom from their abusive biological families. Although the predominantly white and middle-class Castro district earned a reputation as San Francisco’s premier gay neighborhood, these self-described “street kids” built an enduring queer community in the Tenderloin that whitewashed narratives of LGBT progress and pride have obscured.

Until now, unhoused street kids have rarely occupied the center of queer urban history—a field that has privileged “housed populations” with political clout over “people living on the economic margins.”[2] In Kids on The Street: Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, Joseph Plaster offers a theoretically sophisticated exploration of street kids’ spiritual practices and intimate lives, from the late nineteenth century to the 2010s. Instead of portraying the Tenderloin as evidence of San Francisco’s “doom-loop,” Plaster argues the neighborhood served as “an urban stage” upon which street kids creatively performed religious rituals, sexual identities, and forms of kinship outside the heteropatriarchal nuclear family.[3] Drawing upon extensive archival and ethnographic research and over eighty original oral history interviews, Plaster traces the development of a “performative economy,” in which street kids collectively managed the economic and affective impacts of social abandonment and criminalization.[4] Through selling sexual services to older white men, pooling resources with their “street families,” finding under-the-table work in gay businesses, and establishing shared moral standards, street kids created a distinctly queer counterpublic, characterized by an ethos of reciprocity.[5] While Plaster identifies many admirable aspects of the Tenderloin’s queer youth subculture, he avoids romanticizing street kids, arguing their “cooperative relationships” were not always an expression of altruism or political radicalism, but rather a necessity “for mutual survival.”[6] In making this thoughtful and nuanced argument, Plaster joins a growing number of scholars who have critiqued queer and trans studies’ tendency to idealize our non-normative subjects, instead of recognizing their “complex personhood” and flaws.[7]

In his first chapter, Plaster historicizes how Progressive reformers, elected officials, and real estate profiteers transformed the Tenderloin into an impoverished “zone of abandonment,” where the sexual and moral deviancy associated with the poor, Black and brown people, and immigrants was segregated away from white bourgeois families.[8] To urban historians, parts of this chapter will cover familiar territory. However, Plaster’s focus on street kids makes his account unique. Drawing on queer critiques of historical empiricism, Plaster emphasizes continuity across historical eras, arguing street kids’ social and cultural practices remained remarkably consistent from Prohibition to the onset of urban neoliberalism during the 1970s.[9] I was initially skeptical of this claim, but Plaster mobilized a remarkable amount of archival evidence to highlight surprising continuities across much of the twentieth century, leaving this reader satisfied. Through his creative approach to temporality, Plaster portrays the Tenderloin as an intensely spiritual space, in which the past and present blend together in ways that “exceed historical analysis.”[10]

Like prisons and other working-class spaces, the Tenderloin developed its unique sex-gender system, which did not resemble the homosexual/heterosexual binary that gained hegemonic status in the United States after World War II.[11] To develop this powerful argument, Plaster offers a “performance genealogy” of two common sex-gender roles in the Tenderloin: the street queen who performed a highly stylized and youthful femininity; and the hustler who performed a homoerotic masculinity modeled after cowboys, sailors, and soldiers.[12] Because hustlers and street queens often sustained themselves through various forms of sex work, Plaster devotes particular attention to the Tenderloin’s racially stratified sexual economy, demonstrating that white sex workers generally received higher wages than sex workers of color.[13] Given the Tenderloin’s proximity to the Western Addition, a working-class Black neighborhood that was a major center for commercial sex, I was curious to read more from Plaster about the relationship between these two neighborhoods, as well as how anti-Blackness specifically shaped San Francisco’s sexual economies and racial politics.[14]

Broadening his story beyond San Francisco’s municipal boundaries, Plaster persuasively argues the Tenderloin was part of a national migratory circuit, in which street kids traveled from vice district to vice district following seasonal changes, festival patterns, and police crackdowns. Plaster especially highlights street kids’ migration between the Tenderloin and Times Square—a sex district that attracted a largely Black and Puerto Rican group of street kids during the post–World War II era.[15] Through following street kids’ cyclical migrations between San Francisco, New York, and other US cities, Plaster challenges dominant conceptions of homosexual migration, which erroneously assume that all queer subjects move from homophobic small towns to sexually progressive major cities.[16] Urban historians have traditionally focused on gay and lesbian politics within a single metropolitan area. Still, Plaster persuasively critiques the prevailing “community study” model, claiming this “site-bound” methodology obscures transient populations who did not leave behind extensive archival records.[17] Plaster’s sensitivity to archival silences is one of the book’s major strengths, and urban historians will appreciate his capacious approach to place and migration.

In his second chapter, Plaster reveals street kids used syncretic religious formations (“street churches”) to denounce the dominant moral order, which cast their bodies as dirty, sinful, and deserving of familial rejection.[18] Mobilizing Santería liturgies and Catholicism’s “gothic language of abjection,” street churches celebrated street kids as God’s sacred children, and they condemned wealthy white real estate developers who profited from street kids’ suffering.[19] Beyond offering a powerful critique of urban inequality, street churches performed an important economic function, providing food, shelter, and employment for abandoned youth who, as Plaster illustrates, often struggled with drug addiction and profound psychological trauma stemming from childhood abuse.[20] After explaining street churches’ connections with the New Left, Plaster explores the religious congregations of four different queer ministers—the Reverend River Sims (2000s), the Reverend Raymond Broshears (1960s-1980s), the Reverend Michael Itkin (1960s-1980s), and “Saint” Sylvia Rivera (1960s-1990s). Through recalling the interactions between these queer ministers and their congregants, Plaster questions the presumption that Christianity and queerness are incompatible, highlighting deep resonances between Jesus’s teachings and the anticapitalist politics of gay and trans liberation. This is arguably the book’s most emotionally resonant and beautifully written chapter, filled with brilliant analysis and moving accounts of street kids’ religious rituals and personal narratives.

Plaster then turns his attention to Vanguard, a Tenderloin-based political organization that organized a mostly white and male group of street kids against antigay police brutality, youth homelessness, and displacement during the late 1960s.[21] Vanguard has already received extensive treatment from gay and lesbian historians, but Plaster provides a novel interpretation of their activism, arguing Vanguard “built on the preexisting web of reciprocities, kinship networks, and religious practices” among unhoused queer youth.[22] Complementing his archival research, Plaster then explores Vanguard Revisited, a public humanities project that enlisted contemporary trans and queer youth in interpreting and disseminating Vanguard’s history through political theater and letter-writing campaigns. Like their predecessor, Vanguard Revisited grounded their politics in street kids’ daily concerns, protesting a draconian municipal ordinance that criminalized sitting or lying on city streets between 7:00 a.m. and 11:00 p.m.[23]

While the previous chapters offer a thick description of the street kids’ world-making practices, Plaster’s final chapters chronicle how gentrification, the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the rise of broken-windows policing gradually undermined street kids’ performative economy and migratory way of life.[24] During the 1960s and early 1970s, street kids often found work and temporary shelter in Polk Street’s gay-owned bars and coffeehouses, but skyrocketing property values pushed many gay businesses out of the neighborhood, leaving marginally housed youth with fewer economic opportunities and friendly indoor spaces by the turn of the millennium. As Plaster illustrates, this shift had devastating consequences—street kids faced heightened harassment from police officers and wealthy transplants who viewed unhoused youth as “trash” to be swept away. Alarmed by these escalating attacks on street youth, Plaster organized “Lives in Transition,” a public history project that challenged developers and gentrifiers who claimed they were benevolently “cleaning up” Polk Street in the name of public safety and family values. Through organizing a series of mediated conversations between long-term residents and recent transplants, Plaster sought to not only document the neighborhood’s queer history, but also intervene in it.

Filled with fresh insights and original archival and ethnographic research, Kids on the Street is an outstanding book, which deserves a wide readership among urban historians, religious studies scholars, historians of childhood, performance studies scholars, and cultural historians of gender nonconformity, race, and sexuality. Urban historians will learn much from Plaster’s analysis of street kids’ migration patterns, and childhood historians will particularly appreciate how Plaster captured the affective impacts of familial abuse and state abandonment. Plaster writes about street kids with a remarkable amount of generosity and care, and his book offers an exceptional model of ethically engaged, queer historical scholarship. In an era when gentrification, the racist and classist demonization of unhoused people, and anti-trans statecraft threaten the livelihoods of far too many young people, Kids on The Street offers essential context for these disturbing developments. More importantly, Kids on The Street treats abused and abandoned youth not as one-dimensional victims, but as complex historical actors with something meaningful to say about a violent world that spectacularly failed them. Young people today, whether on the streets of San Francisco or in a domestically violent household, deserve more than pity—they deserve solidarity and material support.

Alex Melody Burnett (she/hers) is a PhD candidate in the joint History and Women’s and Gender Studies program at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She is a feminist historian of the twentieth-century United States who specializes in transgender history, queer urban history, carceral studies, and the history of social movements. Her dissertation explores the criminalization of gender nonconformity in the San Francisco Bay Area, tracing how trans and gender nonconforming people encountered and transformed the criminal legal system during the age of mass incarceration. Alex’s scholarly writing has appeared in the Journal of The History of Sexuality, and she is a board member of the Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) History.

Featured image (at top): Mural above the new Tenderloin Neighborhood Community Center. Photograph by Boortz47, 2018, flickr.com. CC BY-NC 2.0 DEED.

[1] Susan Stryker, “MTF Transgender Activism in The Tenderloin and Beyond, 1966-1975,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 4, no. 2 (1998): 349-373. Nan Alamilla Boyd, Wide Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Christina Hanhardt, “The White Ghetto: Sexual Deviancy, Police Accountability, and the 1960s War on Poverty,” in Safe Space: Gay Neighborhood History and The Politics of Violence (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013). Martin Meeker, “The Queerly Disadvantaged and The Making of San Francisco’s War on Poverty,” Pacific Historical Review 81, no. 1 (2012): 21-59.

[2] Joseph Plaster, Kids on The Street: Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco’s Tenderloin (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023,: 7.

[3] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 6.

[4] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 5.

[5] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 14.

[6] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 7.

[7] I borrow the phrase “complex personhood” from Avery Gordon, who described it as the notion that “all people (albeit in specific forms whose specificity is everything) remember and forget, are beset by contradiction, and recognize and misrecognize themselves and others.” See: Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters: Haunting and The Sociological Imagination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 4. For critiques of idealization of non-normativity, see: Kadji Amin, Disturbing Attachments: Genet, Modern Pederasty, and Queer History (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017). Jules Gill-Peterson, “The Trans Woman of Color’s History of Sexuality,” Journal of The History of Sexuality 32, no. 1 (January 2023): 93-98.

[8] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 38.

[9] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 36.

[10] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 27.

[11] Regina Kunzel, Criminal Intimacy: Prison and The Uneven History of Modern American Sexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[12] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 52-61.

[13] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 50.

[14] For more on the Western Addition and commercial sex, see: Josh Sides, Erotic City: Sexual Revolutions and The Making of Modern San Francisco (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 61-64. For more on anti-Blackness in San Francisco, see: Savannah Shange, Progressive Dystopia: Abolition, Antiblackness and Schooling in San Francisco (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

[15] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 58-59.

[16] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 67.

[17] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 46.

[18] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 71.

[19] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 72.

[20] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 92.

[21] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 134.

[22] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 110.

[23] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 155.

[24] Plaster, Kids on the Street, 221.